That Mrs Caird sympathises with the Nihilists goes without saying; she is the priestess of revolt, and sympathises with revolters everywhere. — William Thomas Stead (519).

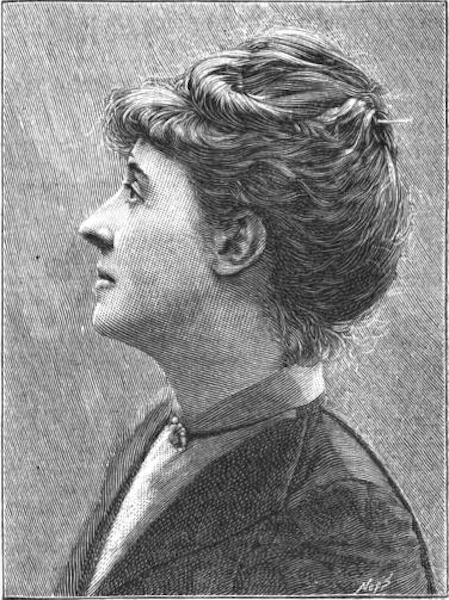

Mona Caird (née Alice Mona Alison), who was also known as Alice Mona Henryson Caird, 1854–1932, was an important New Woman essayist and novelist, social commentator, and campaigner against vivisection and eugenics. Her radical views on undesired marital sex, birth control, single motherhood, mother-daughter relationship, and free relationships after marital breakdown, expressed in her polemical essays and novels, prompted the emergence of the vivid marriage debate in the last decade of the Victorian era and in the early twentieth century.

Little is known about Mona Caird’s life because she left no autobiography or a journal, and biographical information is very sketchy and incomplete. She was born as Alice Mona Alison on 24 May 1854 in Ryde on the Isle of Wight as the only child of the 19-year-old Matilda Ann Jane Alison née Hector, from a well-to-do family in Schleswig-Holstein (then part of Denmark, now Germany), and the 40-year-old John Alison, a wealthy Midlothian landowner and inventor of vertical boilers and retorts. Mona’s family moved from the Isle of Wight to their new home in central London at 90 Lancaster Gate, near Kensington Gardens, although some sources speculate that they may have spent some time in Australia (Brown 144-145). Mona received conventional middle-class upbringing and later she continued self-education. She was fluent in both German and French, and as an avid reader she studied the works of contemporary English, French and German writers and philosophers. She was widely read in ethnology, economics, social philosophy and history. Her greatest formative intellectual influence was John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women (1869). Caird drew on his idea of the equality between the sexes to support her own beliefs and arguments. Other writers and thinkers who had influence on Mona Caird’s intellectual and literary development were Percy Bysshe Shelley, Herbert Spencer, Charles Darwin and T.H. Huxley (Bland 126). Her extensive readings and growing interest in the then much-discussed Woman Question led her, as she said, to grow up rebellious against traditional attitudes to gender inequality, marriage and motherhood.

In 1877, at 23, she married at Christ Church, Paddington, London, a wealthy Scottish gentleman farmer, James Alexander Henryson Caird (1847-1921) of Cassencary near Creetown, Kirkcudbrightshire, on the southwest coast of Scotland. He was the son of a well-known agriculturalist and MP, Sir James Caird, who had come from a distinguished Scottish family. James’s mother was a descendant of the Renaissance poet Robert Henryson. Mona’s husband was 8 years older than she was. They had only one child, a son called Alister James, born in 1884, who was educated privately after which he attended Magdalen College, Cambridge. Although Mona and her husband enjoyed a fairly good relationship until his death in 1921, they in fact had a marriage-at-a-distance, leading undisturbed, parallel lives with a set of separate friends due to their contradicting interests and outlooks on many issues. Whereas her husband spent most of his time with their son in his Scottish family estate, she either resided in their London house or travelled widely in Europe, writing polemical articles and books and participating in different associations and movements of a social, political and spiritual nature related to her interests.

In 1889, Caird took a trip to the Carpathian Alps with her close girlhood friend Elizabeth Sharp, a noted anthologist. In 1890-91, she spent the winter in Rome with Elizabeth, her husband William, a poet belonging to the Celtic Revival, who used a feminine literary pseudonym, Fiona Macleod, and the beautiful young married woman, Edith Wingate Rinder, a relative of the Cairds. Soon William and Edith fell in love with each other when they found that they shared a deep common interest in Celtic culture. Later Rinder became a writer and a translator of Breton folklore. Surprisingly, Elizabeth, probably on the advice of Mona, who did not have a high opinion about marriage as an institution, did not fall into despair, but on the contrary, expressed a belief that her husband’s platonic attachment was a necessary incentive to his poetic development. Both Mona and Elizabeth believed that each person should take advantage of any opportunity for personal and spiritual fulfillment.

As a New Woman, Mona Caird was a committed feminist who became engaged in a number of public activities for women’s rights. In London, she began to earn her living by contributing articles to a number of influential magazines, including the radical quarterly Westminster Review and the Fortnightly Review. In 1878, she subscribed to the Central Committee of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage. In the mid-1880s she attended meetings of the Men and Women’s Club, founded by the prominent freethinker, socialist and later eugenicist Karl Pearson (1857-1936) in order to carry serious discussion about the relations of the sexes, marriage, sexuality, friendship, and prostitution, but she was never its formal member. The Club’s female members or guests included such radical feminists as Olive Schreiner (1855-1920), a South African New Woman writer and anti-war campaigner, Annie Besant (1847-1933), a theosophist, Eleanor Marx (1855-1898), Karl Marx’s youngest daughter and a socialist activist, and Emma Brooke (1844-1926), a novelist and a campaigner for the rights of women. In May 1887, Caird attended a widely publicised debate on birth control in the Club (Youngkin 87).

Mona Caird became a freethinker, and for four and half years (14 June 1904 — 19 January 1909) was a member of the Theosophical Society founded by Madame Blavatsky. In 1878, Caird joined the National Society for Women’s Suffrage, and in 1891, the Women’s Franchise League and the London Society for Women’s Suffrage. She strongly believed that women’s suffrage was closely connected with their emancipation. In 1892, she read her paper ‘Why Women Want the Franchise’ at the Emancipation Union conference. In 1908, she wrote a letter to the Times in which she argued that only by direct representation could women achieve true freedom and equality (Brown 144). In the same year, she published the essay ‘Militant Tactics and Woman’s Suffrage’ and participated in the second Hyde Park Demonstration for women’s suffrage. She was appointed member of the first Council of the Women’s Emancipation Union, alongside with other campaigners for women’s rights and suffragists, such as Agnes Pochin (Agnes Heap), Florence Dixie, Harriet McIlquham and Agnes Sunley. Besides, she was a member of the London Society for Women’s Suffrage from 1909 to 1913. During the late 1880s and throughout the 1890s, she published polemical essays and two important novels on marriage, family and gender relations. Caird was also a member of the Society of Authors and the feminist Pioneer Club. She was also loosely involved with the Women’s Social and Political Union in 1907-1908. During World War I, she wrote against brute force as a means of social progress, advocating instead education, international communication, and travel as a means of fostering global citizenship.

At the turn of the century, Caird, a vehement opponent of vivisection, became involved in the animal protection movement. She saw parallels between the treatment of animals and women. For a short time she was President of the Independent Anti-Vivisection League, whose members included Annie Besant and George Bernard Shaw (Hamilton LI). This commitment estranged her from both her husband and son, who were fond of hunting and fishing. In 1895, she published The Sanctuary of Mercy, in 1896 Beyond the Pale, and in 1902 a play, The Logicians: An Episode in Dialogue, which dealt with the issue of animal protection. Caird was also sympathetic to vegetarian movements. She strongly criticised the new pseudoscience of eugenics. In England, the supporters of eugenics included Herbert Spencer, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, and its active opponents were apart from Caird Thomas Huxley, Gilbert Keith Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc. Caird warned that if eugenic principles were accepted, the rights of the weak would be imperiled. She did not approve of the eugenic ideas of state controlled motherhood, propagated, among others by Wells. In her polemical essays, ‘Caird appropriated the scientific rhetoric of the social purists and eugenists in order to rework their arguments, exposing the biases inherent in the new discourse of biology and reclaiming the importance of environment and culture in shaping individuals’ (Richardson 182). In her approach to eugenics Caird also differed radically from some other New Woman writers, such as Sarah Grand (1854-1943) and George Egerton (Mary Chavelita Dunne Bright, 1859-1945), who were under the spell of so-called positive eugenics. Caird exposed the fallacy of biological determinism on which eugenics was based; a belief that human behaviour is mostly controlled by a person’s genes and inherited traits. Instead, she emphatically emphasised the environment as the source of knowledge, learning and behaviour. Caird died on 4 February 1932 in St. John’s Wood, a district in the City of Westminster.

Literary friendships

While in London, Mona Caird had a wide circle of female and male literary friends, some of whom shared her ideas about marriage and women’s rights. Thomas Hardy was an early admirer of her work and feminist ideas. ‘As his relationship with Emma cooled in his mid-forties, Hardy became intensely drawn to younger and more attractive women’ (Greenslade in Mallett 26). He was particularly interested in the work of New Woman authors, including Caird, whose views on marriage and divorce were very close to his. Caird was also friendly with John Chapman (1821-1894), the editor and owner of the Westminster Review. Her most outstanding female ‘New Women’ friends included Dinah Mulock Craik (1826-1887), Augusta Webster (1837-1894), Olive Schreiner and Sarah Grand. Caird corresponded with Jane Francesca, Lady Wilde (1821-1896), known under her pen name Speranza, mother of Oscar Wilde, who was not only a supporter of the Irish nationalist movement but also an early advocate of women's rights, and campaigned for better education for women. One of Caird's closest friends was the German-born English poet, fiction writer, biographer, essayist and literary critic Mathilde Blind (1841-1896), with whom she had ‘an intimate communion’, ‘both physical and mental’ (Diedrick 639). Her other friends included the writer and editor Elizabeth Sharp (1856-1932), to whom she dedicated the novel, The Wing of Azrael, Rosamund Marriott Watson (1860-1911), a poet, nature writer and critic, Katharine Tynan (1861-1931), an Irish novelist and poet, and Schreiner.

Conclusion

Mona Caird was one of the most militant and active New Woman writers, who had radical views on the patriarchal institution of marriage and motherhood. In her feminist essays and novels, Caird, along with other New Woman writers, challenged the Victorian conceptions of femininity, filial duty, marriage and domesticity. She criticised large families and multiple pregnancies, which subordinated women and thwarted their personal development. She believed that maternity does not exclusively define womanhood. Caird was an important forerunner of women’s rights as well as animal rights and anti-vivisection movements. Her ideas about gender equality and personal freedom provided impetus for the second-wave feminism in Europe and the United States.

Bibliography

Bland, Lucy. Banishing the Beast: English Feminism and Sexual Morality, 1885–1914. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1996.

Brown, Stuart, ed. Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British Philosophers. Volume 1. Bristol: Thoemmes Continuum, 2005.

Caird, Mona. Beyond the Pale: An Appeal on Behalf of the Victims of Vivisection. London: Bijou Library, 1896.

____. The Daughters of Danaus. Gutenberg Project.

____. The Morality of Marriage and Other Essays on the Status and Destiny of Woman. London: George Redway, 1897.

____. The Wing of Azrael. Montreal: John Lovell & Son, 1889.

____. Romantic Cities of Provence. New York: Charles Sbribner’s Sons and London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1906.

Diedrick, James. ‘The Hectic Beauty of Decay: Positivist Decadence in Mathilde Blind’s Late Poetry’, Victorian Literature and Culture, Vol. 34(2), Fin-de-Siecle Literary Culture and Women Poets (2006), 631-648.

Gates, Barbara T. Kindred Nature: Victorian and Edwardian Women Embrace the Living World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Gullette, Margaret Morganroth. Afterword, in Mona Caird, Daughters of Danaus. New York: The Feminist Press, 1989, 493-534.

Hamilton, Susan, ed. Animal Welfare & Anti-vivisection 1870-1910: Nineteenth-Century Women’s Mission. Frances Power Cobbe. London and New York: Routhledge, 2004.

Heilmann, Ann. New Woman Strategies: Sarah Grand, Olive Schreiner, Mona Caird. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2004.

___. ‘Mona Caird (1854–1932): Wild Woman, New Woman, and Early Radical Feminist Critic of Marriage and Motherhood’, Women’s History Review, 5 (1996), 67–95.

Mallett, Phillip, ed. Thomas Hardy in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Richardson, Angelique. Love and Eugenics in the Late Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Sinclair, May. The Creators. Edited by Lyn Pykett. Birmingham: The University of Birmingham Press, 2004.

Stead, William Thomas. ‘Mrs. Mona Caird in a New Character’, Review of Reviews, 1893(7).

Youngkin, Molly. Feminist Realism at the Fin de Siecle: The Influence of the Late-Victorian Woman's Press on the Development of the Novel. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2007.

Last modified 20 February 2019