Ray Dyer traces Tennyson's growing importance to Lewis Carroll, as he came to fill the role of father-figure, as well as becoming the younger writer's admired "poet-bard." Note the form of multi-volume citations below. Diaries, I: 51-52 note 1 appears as follows: Diaries 1.51-52n1. [Click on the illustrations to enlarge them, and for more information about them where available. — JB]

The Amicable Years, 1858-64

1858. Dated 6 Jan. 1858 on the reverse of the relevant photograph of Tennyson's niece Agnes Grace Weld, Carroll inscribed two stanzas of new verse to accompany the Little Red Riding Hood pictorial theme (Diaries, 3: 89 & n138). Full of rich Arthurian imagery and reminiscent of Tennyson's published works of 1843, the "ringlets wild" of the maiden's hair, and the "dark, dark wood" of her setting (stanza I) are seen as the context for "the Wolf" (stanza II) of the young girl's dangerous situation.

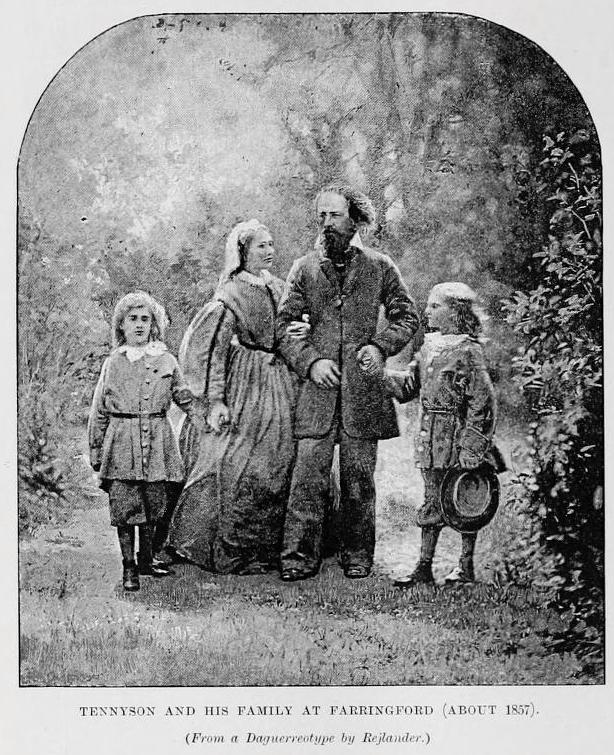

Tennyson and his famiy at Farringford, phtgraphed by Oscar Rejlander.

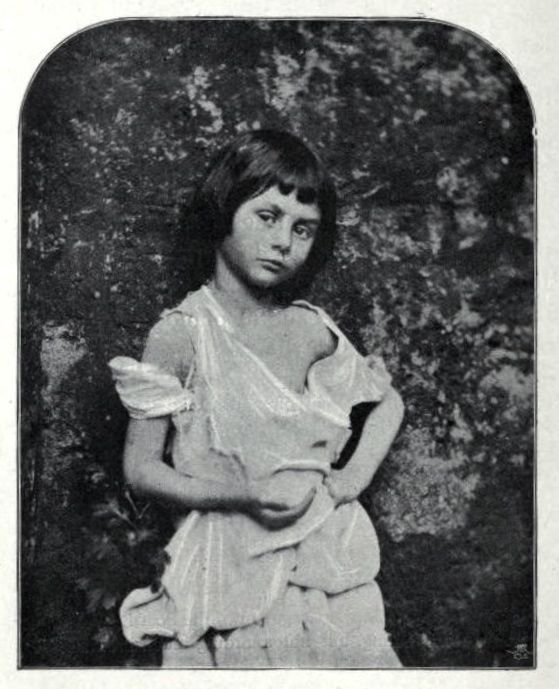

1859. In the April Easter vacation Carroll holidayed on the Isle of Wight, close to the Tennysons' home at Freshwater, Farringford. Calling upon the Poet Laureate he is again [see Carroll-Tennyson Chronology, 1857] well received, and is shown Tennyson's study and books (Diaries, 4: 13-25). In a discussion of the literary uses of moonlight the older poet shows Carroll precise lines in his poem "Margaret" from Poems of 1832 where such effects are employed: "O rare pale Margaret,/ What lit your eyes with tearful power,/ Like moonlight on a falling shower?"; and again, "Like the tender amber round,/ Which the moon about her spreadeth…." Most if not all of Tennyson's books were owned and collected by Lewis Carroll over his lifetime (Stern, Lots 351, 352, 424 and others), and in many editions. Carroll would display moonlight and other atmospheric effects in a number of his own subsequent writings, for example in the first Alice book and both Sylvie and Bruno books (1889: XIV; 1893: XIX) and the later collected poems of 1898. Tennyson published his Idylls of the King, another bedrock for the Victorian century's Arthurian valedictions. A letter of 4 June from Christ Church to Tennyson's wife shows Carroll discussing his photograph of Alice Liddell as Beggar-Child, in which Alice Liddell (then aged seven) is dressed as a beggar-girl. Tennyson declared it "the most beautiful photograph he had ever seen," (Diaries, 4: 14-20; see the entry for 1864, for further photography on the Isle of Wight). How Carroll must have basked in such appreciation, and doubtless have been further convinced that his future lay not only with his rigorous and precise mathematics work, but also with his photography and his poetry, with its Romantic imagery.

Carroll's photograph of Alice Liddell as a beggar-child

1860. Carroll continued sending to the periodicals his short serious poetry pieces, as he had previously with his poem "Solitude" of 1853. New poems of this time included the sentimental "Faces in the Fire," which he posted early in the New Year to Charles Dickens as editor of All The Year Round, and which appeared in no. 42 (February). Blazing homely firesides were firmly a part of Victorian winters, with Dickens himself having earlier set his own evocative Master Humphrey's Clock in the chimney-corner with its "ruddy blaze." By October, however, Carroll turned his offerings towards College Rhymes, the relatively new venture from 1859 for members of Oxford and Cambridge universities. His still humorous "A Sea Dirge" appeared in Vol. 2, and Carroll himself would soon become editor of the poetry periodical. Meanwhile he continued to holiday on and visit the Isle of Wight in his pursuit of the Poet Laureate, though in this period of missing journals only the slimmest of sound details are available (Diaries 4: 4-40).

1861. At Christ Church Carroll proceeds to Holy Orders, but with his ordination only to deacon, defying both his father and Bishop Wilberforce, and the influential Dr. Edward Pusey, his early sponsor. His holidays that year were presumably (see the entry for 1862) once more close to Tennyson's Isle of Wight retreat. The year saw the beginnings of increased tourist activity on the island, after the death of Prince Albert, with Queen Victoria then making more use of her secluded residence at Osborne House. Tennyson's reluctance to be lionised [1854] again threatened to emerge (see 1869). As Poet Laureate he nevertheless penned a funeral eulogy for the Queen's departed husband in 1862. Carroll's own romantic poetry leanings had now produced "Three Sunsets" and "After Three Days," the former ultimately becoming the title of the final collection of his poetry produced during his lifetime (see the entry for 1898).

1862. January saw Edward Moxon of London publishing a slim anonymous volume, An Index to "In Memoriam". This was the work of Lewis Carroll, aided by his sisters, and assiduously treated the earlier work by Tennyson [1850, though actually dated MDCCCXXXIII, year of the death of Tennyson's close friend Arthur Henry Hallam]. Carroll's personal private journals, after a four year hiatus since May 1858, have now become available for consultation, yielding many useful details about his day-to-day life. From May 1862 to September 1864 his Diaries Vol. 4 shows some nineteen citations for Tennyson affairs after the earlier and partially reconstructed period, though these shrink to a bare trickle before the close of Volume 4. Carroll's interests in resurgent medievalism and all things Arthurian continued, with his poem about a knight, frankly erotic in one part, entitled Stolen Waters. This appeared in the May issue of College Rhymes, with decided overtones of Tennyson and a few important others. By October Carroll had become editor of the inter-varsity poetry journal, and quickly turned his attention to requesting permissions for the dedications of his annual bound-volumes: from Tennyson (vol. 3), Matthew Arnold, William Makepeace Thackeray, and a very few others, including the American Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Tennyson's funeral valediction for Prince Albert, "The White Flower of a Blameless Life," which was worn "Before a thousand peering littleness's…," was published as an insertion into the Laureate's revised and now dedicatory Idylls of the King. On the beach at the Isle of Wight this year Carroll was greatly impressed by and made friends with the lively family of writer Sir Henry Taylor , and especially with his engaging little daughter Una, born in 1857 (Diaries 4: 125 & n98). The friendship, as with most of Lewis Carroll's, was assiduously cultivated, and continued beyond this first beach encounter. The confluence of many considerations from the known biography leads to the recommendation of 1862-63 as a high point in Lewis Carroll's personal life, both with regard to Alice Liddell and her sisters at Christ Church, and with Tennyson at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight.

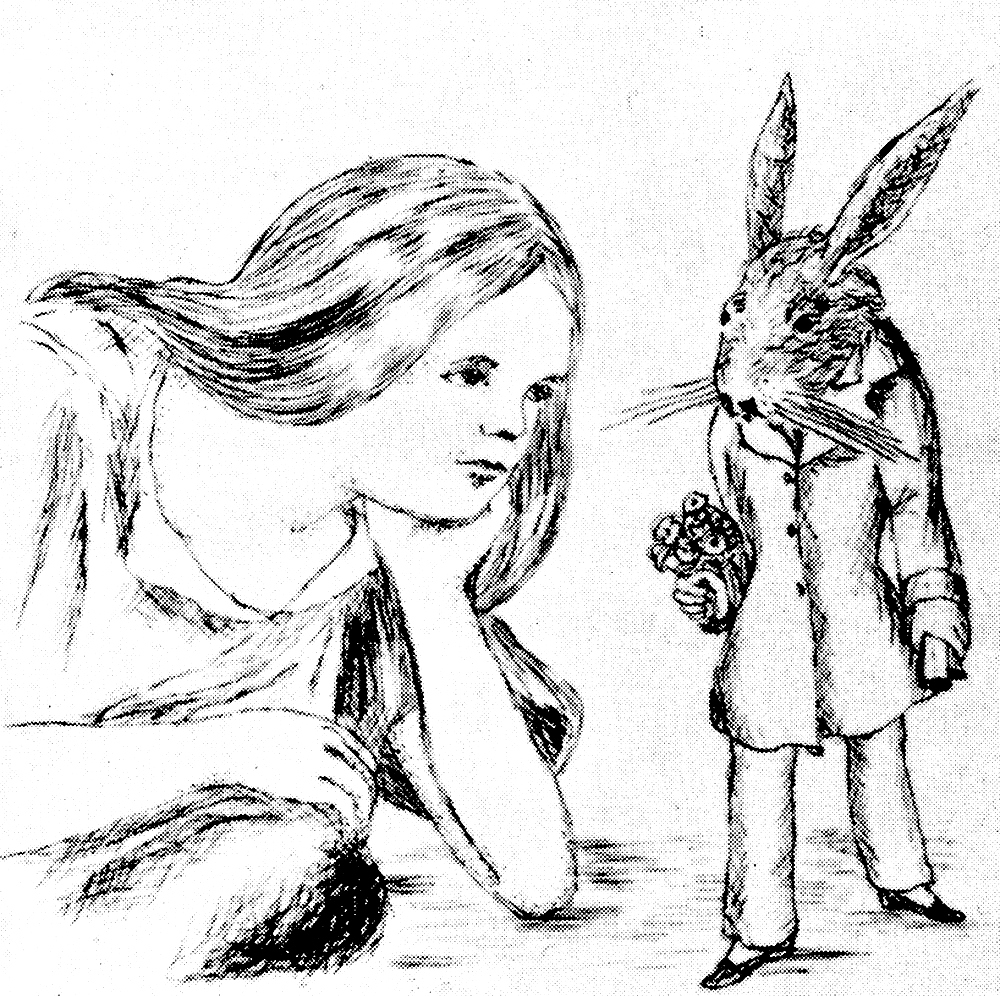

Carroll's own illustration of Alice and the White Rabbit.

1863. This the second year of intense oral storytelling by Lewis Carroll to the three Christ Church Liddell sisters during summer boating outings on the nearby river. Alice and her sisters would finally persuade him to write the endless tale down, and he also opted to illustrate it himself, thereby assuring an inevitably larger extra workload. Subsequent social changes beyond his control at Christ Church, and linked to the developmental maturation of Alice Liddell, would conspire to reduce his eventual satisfaction on presenting the hand-produced private volume. That presentation would take place crucially only late the following year, on Saturday 26 November 1864, with Alice then half-way between 12 and 13 years of age, and with the completed manuscript "sent to Alice" (Diaries 5: 9) rather than delivered personally to the other side of their shared Christ Church "Tom" quad. Carroll would later, in 1865, be sure to send Tennyson a copy of the new venture in children's fantasy when it was published, much as he had sent him the photograph of Agnes Grace Weld dressed as Little Red Riding Hood in 1857.

1864. This year Tennyson published Enoch Arden, and was visited at Freshwater by Guiseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882), Italian soldier and hero of the unification of Italy. In August Lewis Carroll returned to photograph at Farringford, having become disenchanted with town-life in London during the summer - friends and family of writer George MacDonald away, and society photographer Lady Hawarden of Princes Gardens, South Kensington, missed by minutes amongst other disappointments. Arriving at Freshwater he found the Poet Laureate also away that summer, and had to socialise with Mrs. Tennyson and the two small boys as his subjects; with the various attendees of the Freshwater annual school feast; and with another soon to be famous photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron at nearby Dimbola Lodge (Diaries 4: 342, 344 & passim). Further disappointments clearly remained with the disconsolate Carroll, who packed up his cumbersome boxes of photographic equipment with the prophetic remark "Went over for the last time to Farringford" (Diaries 4: 19 August). The response of Tennyson on his return can only be guessed at, and Emily Tennyson's Farringford Journal also closes down that year. Carroll's own succeeding Volume 5 of his published private journal covers the period September 1864 to January 1868, with only a single mention of Tennyson, and that in a list of recipients of copies of his new venture of 1865, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Clearly, their relationship had altered. (See Part Three (coming shortly)).

Links to related material

- Part One, 1832-1857: The Overtures

- Part Three, 1865-1876: A Melancholy Interregnum

- Part Four, 1877-1889: A Watershed and Acceptance

- Part Five, 1889-1898: Final Glances

- A (general) Lewis Carroll Chronology, 1832-1898

- An Alfred Lord Tennyson Chronology

- Lewis Carroll's "Stolen Waters" in Context

Bibliography

Lewis Carroll. Alice's Adventures Underground. Macmillan: London, 1886.

_____. Sylvie and Bruno. Macmillan: London, 1889.

_____. Sylvie and Bruno Concluded. Macmillan: London, 1893.

_____. Three Sunsets and Other Poems. Macmillan: London, 1898.

_____. Lewis Carroll's Diaries. The Private Journals of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. Ed. Edward Wakeling. Vols. 4 & 5. Lewis Carroll Society of England, 1997 & 1999.

Stern, Jeffrey. Lewis Carroll's Library. Lewis Carroll Society of North America: Carroll Studies No.5, 1981.

Tennyson, Emily. The Farringford Journal of Emily Tennyson, 1853-1864. Isle of Wight: County Press, 1986.

Created 16 June 2022