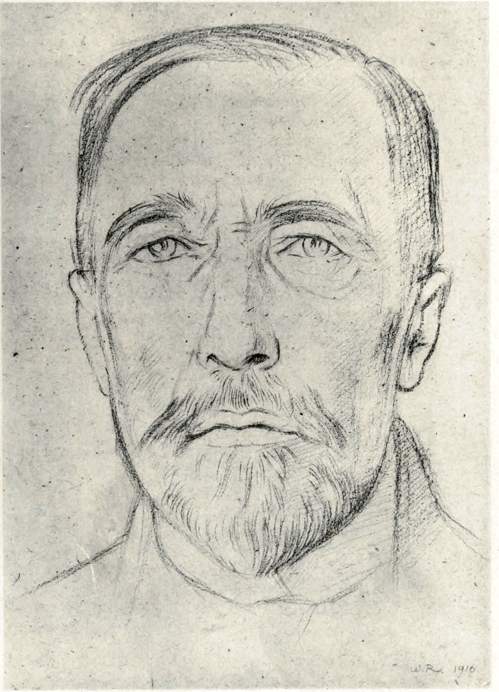

Conrad by William Rothenstein. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

A member of an eminent group of fin de siècle writers that includes Stephen Crane, Robert Louis Stevenson, H. G. Wells, and Henry James, the British short story writer and novelist Joseph Conrad was born in Russian-occupied Polish Ukraine in 1857, the son of Polish aristocrat and militant nationalist Count Apollo Korzeniowski. His father, who translated Victor Hugo's Les Travailleurs de la mer and Dickens into his native tongue, was exiled by the Russians to Vologda in 1862. When the boy was seven his mother died of tuberculosis; his father lived in exile until 1869, when Czarist authorities permitted him to move south; however, after that remove, when young Conrad was just eleven, his father died. He was then adopted by his mother's uncle, the indulgent Tadeusz Bobrowski. At the age of seventeen he began a long period of adventure at sea. As a member of the French merchant marine sailing out of Marseilles, young Conrad was implicated in a Carlist conspiracy to place the Duke of Madrid on the Spanish throne. After a suicide attempt, Conrad joined the British merchant service in 1878.

Not yet twenty-one, he learned English by reading the London Times, Carlyle's Sartor Resartus , and Shakespeare's plays. In 1884, Conrad became a naturalized British subject and gained his master's certificate. In the ten years that followed, he sailed between Singapore and Borneo, voyages that gave him an unrivaled background of mysterious creeks and jungle for the tales that he would write after 1896, when he retired from the sea to settle in Ashford, Kent, with his new wife, Jessie Chambers.

Primarily seen in his own time as a writer of boys' sea stories, Conrad is now highly regarded as a novelist whose work displays a deep moral consciousness and masterful narrative technique. Influenced by Henry James, Conrad's finest works are Nostromo (1904), Heart of Darkness (1899), and Lord Jim (1900). His early novels, including Almayer's Folly (1895), An Outcast of the Islands (1896), and The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897), are full of romantic description in an atmosphere of mystery and brooding. In Tales of Unrest (1898), "Youth" and Other Tales (1902), and Twixt Land and Sea (1912) appeared such outstanding short stories as "Typhoon" and "The Shadow-Line" that describe the testing of human character under conditions of extreme danger and difficulty. Throughout his fiction Conrad is concerned with moral dilemmas, the isolation of the individual to be tested by experience, and the psychology of inner urges in both groups and individuals. His semi-autobiographical The Mirror of The Sea (1906) and Some Reminiscences (1912) (published in the States as A Personal Record ) testify to his high artistic aims.

Conrad did not find shore-life easy. His expedition to the Belgian Congo had left him with malarial gout, which afflicted his wrist so much that he often found writing painful. He was never a quick or fluent writer; he thought it a good day when he could produce as little as 350 words with which he was satisfied. After the publication of his first book, which had taken Conrad some five years to write (and which had survived the African jungle, shipwreck, and a Berlin railway cloakroom), Edward Garnett (writer, critic, and publisher's reader) asked, "Why not another?" Gradually Conrad settled down to write for a living. Although perceptive judges such as John Galsworthy and H. G. Wells praised him, the English reading public was slow to recognize the merit of his work.

Conrad uses fiction to analyze the macrocosm (world at large) by presenting objectively and scientifically a microcosm such as a ship's crew. As a young merchant sailor Conrad had been cut off from family, friends, and country; this essential loneliness he conveys in his tales set on the sea and in exotic locales. His sense of isolation stems from the fundamental differences that existed between himself and his fellow seamen--in age, culture, language, education, and experience. However, his remoteness from the British reading public, and his consequent his lack of knowledge about what makes a popular novel, makes his stories all the more real. Conrad often maneuvers to keep the reader at a distance from the characters in order to view them objectively. For example, in writing "The Inn of the Two Witches" in the winter of 1912 for the London Pall Mall (1913) and New York Metropolitan (May, 1913) magazines he resorted to another "Chinese box" narrative technique: an early twentieth-century book-collector recalls some years before having found a manuscript which contained a story (presumably written in the first person).

Here as elsewhere, the world is seen by Conrad as a place of unending contention between the forces of darkness and dissolution on the one hand and those of brotherhood, duty, and bravery on the other; this belief is sometimes referred to as Manich�ism, an early Christian heresy. Conrad divides all mankind into two types--the visionaries (who are truly 'young' no matter what their chronological age) and the cynical realists. Conrad implies that a man is already dead if he has lost his ideals and visions. The sea is always present in Conrad's stories; for him, it symbolized the physical, emotional, and mental environment of the individual (as represented by the ship�see, for example, the stories "The Secret Sharer," "Typhoon," and "Youth"). Conrad shows how superficial are rational control and civilisation. Youth, full of romantic visions and idealism, encountering the sheer corruption of the Darwinian jungle, may be overwhelmed by the experience, as Tuan Jim is at the start of Lord Jim on board the Patna.

References

Benét's Reader's Encyclopedia. 3rd edn. New York: Harper and Row, 1987.

Karl, Frederick R. A Reader's Guide to Joseph Conrad . New York: Noonday, 1960.

Magnusson, M., and Goring, R. (eds.). Cambridge Biographical Dictionary. New York: Cambridge U. P., 1990.

Related Materials

Last modified 4 December 2000