[Philip V. Allingham scanned the illustrations below, adding captions and commentaries — George P. Landow]

n mid 1880 Hardy began to write his eighth published novel, A Laodicean; or The Castle of the Stanceys. A Story of Today. However, he fell ill in October and for the next five months he was bedridden with a bladder infection and could only dictate the text to his wife. The hastily written novel appeared in thirteen monthly instalments in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, with George Du Maurier's illustrations, from December 1880 to December 1881. The first book edition was published in the United States by Harper & Brothers, and the British edition by Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington appeared in three volumes in December 1881.

A Laodicean is regarded as the weakest of Hardy’s novels (Evelyn Hardy 178), although when first published it received relatively good reviews. In fact, it is not worse than, for example, Desperate Remedies or The Hand of Ethelberta, but it remains undeservedly one of Hardy's most neglected and least read novels, due to, it seems, a typical flaw of Hardy’s style — poor credibility and numerous inconsistencies. The shortcomings of the novel can be explained not only by the fact that the author was seriously incapacitated by his illness, but as Geoffrey Harvey has pointed out, Hardy tried to combine unsuccessfully “the medieval form of the morality play with modern social realism” (105). As a result, A Laodicean, which is basically a romance, contains a number of diverse themes, such as medievalism and modernity, the onset of Victorian modern technology (telegraph, photography, railway), gambling, forgery, female sexuality, ambiguous same-sex relationships, male voyeurism, mystery and chance. However, none of these themes is satisfactorily developed and, therefore, the novel lacks coherence and a consistent overall message.

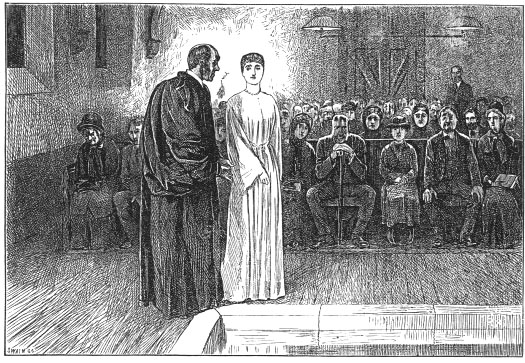

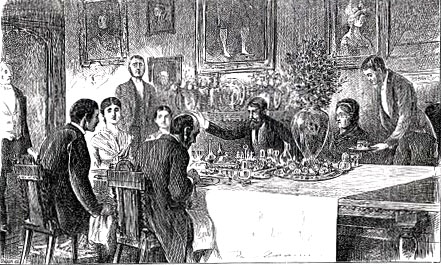

Two of Du Maurier's illustrations that sharply contrast settings. Left: But, My Dear Lady, You Promised . [Paula Decides Against Being Baptised in Her Father's Church] Right: Fine Old Screen, Sir!". [Luncheon in Castle de Stancy, Hosted by Paula Power [Click on images to enlarge them.]

One of the main subjects of A Laodicean, which is subtitled “The Story of Today,” is the clash and contrast between the old and modern worlds. It anticipates the major themes of Tess of the d'Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure. The novel's title refers to the archaic adjective 'Laodicean', derived from the Book of Revelation (3:14-22), which means lukewarm, indifferent, indecisive, or half-hearted, and is the key to understanding the ambivalence of the novel's heroine, who is described as a “modern flower in a mediaeval flower-pot” (38-39). She is both a Romantic heroine and a representative of rootless modern sensibility. In a way, she foreshadows the character of Sue Bridehead from Jude the Obscure but lacks her intellect and moral values.

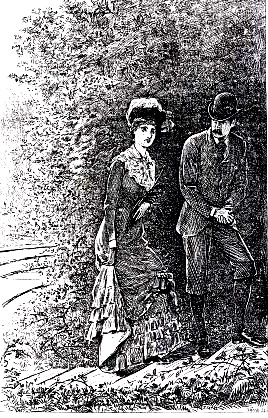

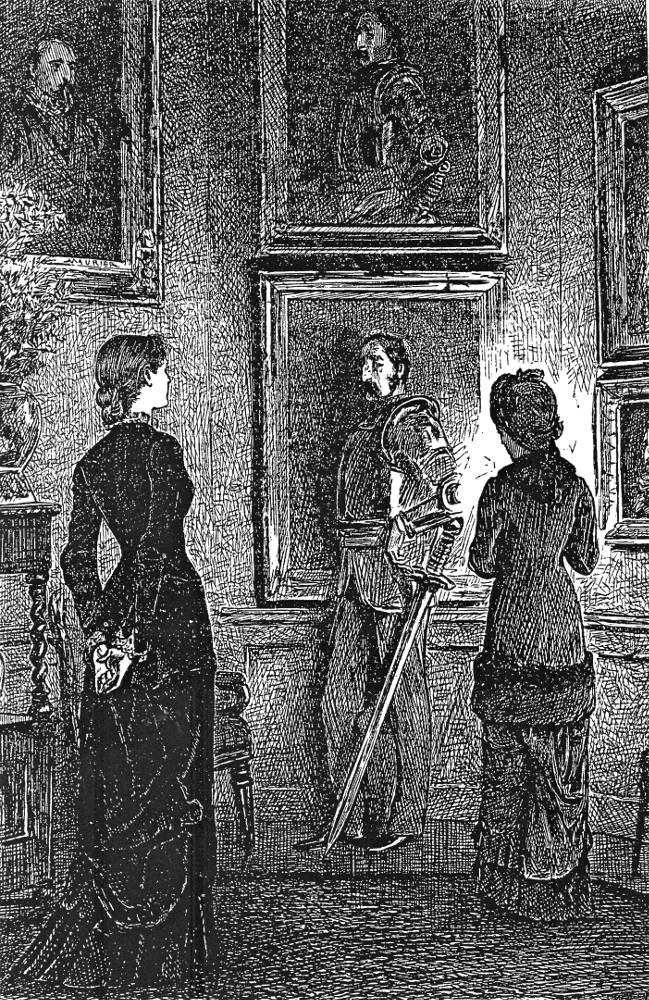

Modern danger and ancient appeal. Left: "What An Escape!" He Said.". [Paula and Somerset Ascend the Hill from the Railway Tracks, Where They Have Just Narrowly Escaped Being Run Over by a Train] Right: "Is The Resemblance Strong?". [To arouse Paula's romantic interest in him through her fascination with the history of the de Stancys and their castle, Captain de Stancy impersonates his cavalier ancestor, Sir Edward, who committed suicide out of unrequited love.] [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The story, which is mostly set at Stancy Castle and the neighbouring town of Markton, as well as in London and some parts of the Continent, concerns Paula Power, the daughter of a wealthy railway contractor and the inheritor of an ancient semi-ruined castle, who cannot decide whether she should marry George Somerset, a talented young architect of independent character, or Captain William De Stancy, the heir of the ancient family which once owned the castle. Although Paula has a romantic relationship with Somerset, she first accepts the marriage offer of De Stancy because she feels attachment with the ancient family. However, when she discovers that De Stancy's illegitimate son, Willy Dare, a photographic amateur, has tried to compromise Somerset by a faked photograph showing him as drunk, she breaks off the engagement and sets out to regain Somerset, whom she still loves. Eventually, Paula marries Somerset and the newlyweds want to settle in Stancy Castle, “the fossil of feudalism,” but the villainous Dare sets it on fire, completely destroying it. The young couple thereupon renounce their interest in medieval and obsolete architecture and build a modern house. However, Paula still remains a 'Laodicean'; she cannot free herself from her fascination with the De Stancys' ancient lineage and their medieval castle. She says to her husband: “But, George, I wish – “And Paula repressed a sigh. Well?' 'I wish my castle wasn't burnt; and I wish you were a De Stancy!'” (431)

Left: "You Will Please To Deliver Them Into No Hands But His Own.". [Paula Entrusts a Purse Intended for Somerset into the Keeping of de Stancy] Right: "Soon a Funeral Procession of Simpler -- Almost Meagre and Threadbare -- Character Arrived?". [Click on images to enlarge them.]

A Laodicean is regarded as Hardy's most autobiographical novel (Gittings 124) with its thinly veiled incidents from early adult life of the author. In fact, according to Harvey, this novel is another “variation on the subject of the poor man and the lady" (105). George Somerset, an aspiring, highly-cultured, young architect with literary interests, is obviously Hardy's alter ego. “Like Thomas Hardy at twenty-two, and like the hero of Desperate Remedies, he is always writing poetry as a young man and admits having written little else, for two years” (178). However, when the novel develops, Somerset's modern outlook is contrasted with Captain De Stancy's old-fashioned romanticism. Yet both men become eclipsed by the personality of Paula, the 'Laodicean' of the title, who exhibits many traces of a Hardy heroine. She is a new woman, who relishes the medieval past, but also owns a telegraph at home (a Victorian predecessor of a computer attached to the Internet) in order to have 'the latest news' . . . and to send love messages to Somerset. Her ambivalence towards the past and modernity reflects the author's own.

Regrettably, the narrative does not flow smoothly; it contains a lot of thematic plot twists to fill a novel twice its length, and makes the reader wonder what the author's point is. Apart from being a telegraph aficionado, Paula also reads the Baptist Magazine, Walford's County Families (a famous a guidebook to the British upper classes and landed gentry), books from a London circulating library, paper-covered light literature in French and choice Italian, and the latest monthly reviews. In Paula's refusal to be baptised, Hardy points to her awareness of religion's artificiality. In another narrative strand Hardy also partly unveils Paula's ambiguous sexuality. Her intimate friendship with Charlotte de Stancy prompts the narrator to imply that she is “a lover rather than a friend” (35), and further, the landlord of the inn tells Somerset about Paula and Charlotte: “they are more like lovers than girl and girl” (50). Earlier, Hardy described an apparent same-sex relationship in Desperate Remedies, but in neither novel does he go further with this then-delicate subject. In many of his novels Hardy uses male voyeuristic gaze as a narrative point of view. In A Laodicean, the narrator describes Captain De Stancy, like a peeping tom, watching Paula exercise in a gymnasium through a hole.

In A Laodicean, Hardy also shows impressively modern technologies at work. The railway, the telegraph, and the camera were dramatically changing lifestyles in Victorian Britain. The telegraph in De Stancy Castle, which represents the past, feudal order, symbolises the intrusion of modernity to the order of the past.

The telegraph had almost the attributes of a human being at Stancy Castle. When its bell rang people rushed to the old tapestried chamber allotted to it, and waited its pleasure with all the deference due to such a novel inhabitant of that ancestral pile. [52]

Paula uses the telegraph for instant messaging and social networking. She types her messages in a special telegraph lingo to make them concise.

'Another message,' she said. — “'Paula to Charlotte. — Have returned to Markton. Am starting for home. Will be at the gate between four and five if possible.'” [52]

However, as in contemporary internet-based social networking, forgery may occur from time to time. The Mephistophelian William Dare, trying to break up Somerset's romantic relationship with Paula, interferes with their communications by counterfeiting a telegram message. He dispatches a faked telegram from Somerset to Paula from Monte Carlo asking her to send him (Somerset) one hundred pounds and save him from disgrace because he lost all his money in gambling. Further, much like someone using Photoshop, Gimp, or other graphic software, Dare alters a photograph of Somerset in order to destroy his relationship with Paula. Luckily for Somerset, all these underhand schemes fail. In showing the potential of modern technologies Hardy repeatedly shows how they are both fascinating and dangerous.

On the surface A Laodicean may seem to be a poorly composed sentimental romance with a typical Hardyan trope of a love triangle, but its presentation of the railway, telegraph and photography as social and cultural phenomena anticipates some of Hardy's concerns about the 'ache of modernity' in his major tragic novels. As Peter Widdowson has pointed out, Hardy aimed “to examine the mentalité of a contemporary society in transition between 'the ancient and the modern'” (97). A Laodicean marks an important phase in Thomas Hardy's literary development.

References and Further Reading

Austin, Linda. “Hardy's Laodicean Narrative.” Modern Fiction Studies 35(2), 1989, 211-222.

Bullen, J. B. “Architecture as Symbol,” in The Expressive Eye: Fiction and Perception in the Work of Thomas Hardy. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986.

Clayton, Jay. Charles Dickens in Cyberspace: The Afterlife of the Nineteenth Century in Postmodern Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

DeVito, Jeremy. “Revising Hardy: The Authorial Plotting of William Dare in A Laodicean.” ‹http://www.iloveliterature.com/laodician_essay.html›.

Drake, Robert. “A Laodicean: A Note on a Minor Novel.” Philological Quarterly 40 (1961), 602-606.

Durden, Mark. “Ritual and Deception: Photography and Thomas Hardy.” Journal of European Studies. 117(1), 2000, 57-69.

East, Melanie. “A 'Network of Hopes': The Romance of Gambling in Thomas Hardy's A LaodiceanThe Comparatist 38, 2014, 27-313.

Hardy, Thomas.A Laodicean. Edited with an Introduction Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.Harvey, Geoffrey.The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy. London: Routledge, 2003.

Ireland, Ken. Thomas Hardy, Time and Narrative: A Narratological Approach to His Novels. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Millgate, Michael. Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Nemesvari, Richard. Thomas Hardy, Sensationalism, and the Melodramatic Mode. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century's On-line Pioneers. New York, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009.

Taylor, Richard H. The Neglected Hardy: Thomas Hardy's Lesser Novels. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1982.

Thomas, Jane. Thomas Hardy, Femininity and Dissent: Reassessing the Minor Novels. New York: Basingstoke: Macmillan; New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999.

Thomas, Kate. Postal Pleasures: Sex, Scandal, and Victorian Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Widdowson, Peter. “Hardy's 'Quite Worthless Novel: A Laodicean.”On Thomas Hardy: Late Essays and Earlier, 93-114. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998.

Wing, George. “ Middle-Class Outcasts in Hardy's A Laodicean.” Humanities Association Review, 27(3), 1976, 229-237.

Related material

- John Collier's Thirty-Three Plates for Hardy's The Trumpet-Major in Good Words

- Collier's First Five Plates for Hardy's The Trumpet-Major

Created 23 April 2015