Very early one morning, I visited the well at Cawnpore, into which 206 women and children, murdered by the order of Nana Sahib, were thrown on the 11th of July, 1857. Sir Evelyn Wood said lately in The Times:— "On July 1 the British prisoners had been moved to a small house containing two rooms, twenty feet by ten feet, with servants rooms at the back, and a narrow verandah running along the front. With them were some Christians, captured when flying from Fathpur and other stations. In all 5 men, 206 women and children were crowded into this building, unfit for an English family, without furniture or even straw for bedding. They were fed on unleaven bread (chupatties) and lentil soup. Twenty-eight died in a fortnight, and then some better food was provided. On July 10 the defeated General, Bala Rao, returned from Aong, with a bullet in his shoulder, and a council was held to decide on future action. There were conflicting views as to fighting, but a unanimous opinion that all prisoners should be put to death. At five o'clock in the afternoon, the Nana sent for the men, and had them put to death in his presence ; and an hour later, he ordered the Sipahi Guard to shoot the women and children, through the doors and windows of the house. Some of the Guard refused, although threatened with [203/204] aim, and eventually five of the Nana's Marathi Guard and some Mahomedan butchers from the city, slaughtered our unhappy people with swords and knives and closed up the building at night. Early the next morn- ing, the dead and dying (some of the women were able to speak and three or four of the children were but little hurt) were thrown into the adjacent well. There was no mutilation, no dishonour attempted, but the horrible massacre, which appalled the whole civilized world, induced reprisals on many thousands who had never been to Cawnpore."

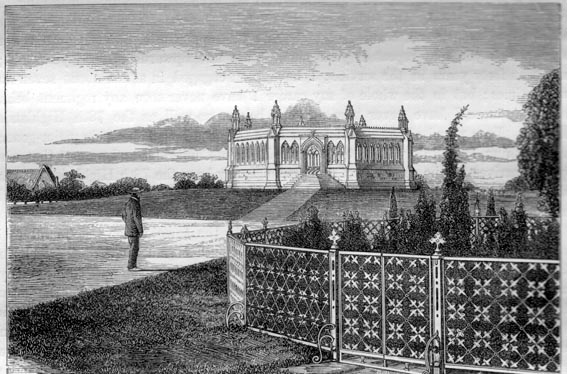

Mausoleum over the Well at Cawnpore. Click on image to enlarge it.

The well is now surrounded by a beautiful garden, and there birds were singing in trees and shrubs when I left the carriage (only pedestrians are allowed in the garden) and walked between cyprus trees to the Memorial. An English soldier sat at a little table, reading a newspaper; and he rose when I approached, and unlocked the iron gate. He removed his hat and led the way to the beautiful Gothic screen, designed by the late Sir H. Yule, R. E., C. B., that surrounds the well; and he said, with characteristic British brevity, 'This is the place where they were thrown in—206 women and children—and that cross yonder marks the place where they were cut up.' Above the well is a beautiful Angel of the Resurrection, in white marble, given by Queen Victoria. The artist, Marochetti, shows the tall, majestic angel with arms folded over two crossed palm leaves. The angel is sleeping, and on its face is an expression of protective love that makes it one of the most beautiful memorials in the world. Over the arch is written: 'These are they that came out of great tribulation'; and on the well is an inscription, detailing the massacre. A simple, white [204/205] marble cross marks the spot where the butchery took place. . . .

A general attack was made by the mutineers, and repulsed by the English, with a loss of over 200 soldiers. An armistice followed; and relying on the Nana's promises, the remainder of the garrison, barely 450 men, women and children, marched down to the boats at Suttee Chowra Ghat, with 60 rounds of ammunition per man. The boats stuck in the mud; and the occupants were immediately fired upon by the Nana's soldiers. Some boats took fire. One floated down the river. Only four men in that boat lived to tell the tale; all the rest were shot. The women and children were taken back to Cawn- pore; and there massacred by order of Nana Sahib. Nana Sahib's bitterness against the English arose from the following facts, endorsed by Sir Evelyn Wood in his articles on 'The Revolt in Hindustan 1857' pub- lished in 1907, in The Times.

The Source of Nana Sahib’s Angry Hostility

Baji Rao, the Ruler of what is now the Bombay Presidency, on being defeated in 1818, abdicated his position as Peshwa in return for the titular rank, a pension of £80,000 and a residence at Bithur, 12 miles from Cawnpore. He adopted Nana Sahib, and later petitioned the Governor that his adopted son might succeed to the title and pension. To this petition he received a vague reply. As no Hindu can hope for a future world unless his heir, begotten, or adopted, performs for him certain funeral ceremonies, it is obvious that Hindus must have resen- ted it. When Baji Rao died in 1851, Nana Sahib applied for a portion of the pension for the support of the late Peshwa's descendants; but this was refused, and Azim Ullah Khan, his representative, failed to get the Calcutta decision reversed in London. Nana Sahib, who was regarded as Peshwa by all Hindus, visited Kalpi, Lucknow and Delhi in 1857. He had seldom previously quitted Bithur, where he had entertained -many officers of the Cawnpore garrison, lending them elephants, horses and carriages. He was generally regarded as a kind, inoffensive but dull native; never- theless he was very astute, and had never forgotten what he considered the confiscation of his estates.

Massacres of Women and Children by both the British Troops and the Rebels

With regard to the massacres of women and children, history tells us that although the English soldiers were forbidden to kill a woman or a child, the native soldiers employed by the English were under no such command. At Delhi, many women and children were killed in the street-fighting by native soldiers, 'houses being decorated with their limbs'; and, in all probability, at Lucknow, the native soldiers killed many more defenceless women and children than Nana Sahib murdered at Cawnpore. But the Nana's deed was premeditated, as he had promised to protect the English people; while at Delhi, and at Lucknow, the native soldiers were carried away by excitement, were mad with victory. [211]

Related material on Cawnpore and the 1857 Mutiny

- The Imperial Gazetteer’s article on “Cawnpoor” a few years before the Mutiny

- An Icon of Empire. The Angel at the Cawnpore Memorial, by Baron Marochetti

- All Souls Memorial Church, Cawnpore

- The Massacre of Cawnpore by R.M. Jephson

- The Suttee Chowra Ghât, or landing place -- scene of the second massacre

- Mausoleum over the Well at Cawnpore

- The 1857 Indian Mutiny (also known as the Sepoy Rebellion, the Great Mutiny, and the Revolt of 1857)

Related material by Margaret Harkness

- The British View of India and Ignorance of Its History

- If Aurungzeb had been a different man . . .

- Harkness on India

Bibliography

Law, John. [pseud., i.e. Margaret Harkness]. Glimpses of hidden India. Calcutta [etc.]: Thacker, Spink & co. [1909?].

Ritchie, J. Ewing. The and Times of William Ewart Gladstone. 5 vols. London: William Mackenzie, n.d. From the Collection of Professor Ernest Chew, National University of Singapore.

Last modified 20 December 2018