An earlier version of this essay was published under the title of "The Legacy of Anne Brontë in Henry James's 'The Turn of the Screw'" in English Studies, Vol. 78, No. 6 (November 1997): 532-44. You may use the images added to it without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the sources and (2) link your document to the appropriate URL or cite it in a print document. Click on the thumbnails for larger pictures.

3. Wrestling with demons

he parallels between the two narratives continue. In particular, there is the continuing shock of disillusion. Seven-year-old Tom Bloomfield is not just insensitive. Billed as "a generous, noble-spirited boy, one to be led, but not driven, and remarkable for always speaking the truth," to Mrs Bloomfield he had seemed "to scorn deception." Agnes had responded to the mother's opinion with a relieved aside: "this was good news." The irony, however, is soon apparent. For Tom is found to be simply shameless. These children, we are told, like the pair at Bly, are "remarkably free from shyness" (405), and soon begin to reveal worse flaws than spurring on a wooden rocking horse. Agnes had hoped "[t]o train the tender plants, and watch their buds unfolding day by day" (400), much as James's governess looks forward to the prospect of supervising Flora: "To watch, teach, 'form' little Flora would be too evidently the making of a happy and useful life" (8). Such pleasant and idealistic visions now evaporate entirely. Instead, Agnes finds herself wrestling with demons, almost as dramatically as the governess would find herself doing at Bly. In Tom's "most violent moods," for instance, Agnes's "only recourse was to throw him on his back, and hold his hands and feet till the frenzy was somewhat abated" (412). A sign of her sexual repression, perhaps — an indication of the need which is later answered by the obliging curate Mr Weston? Or a fierce and perversely physical denial of potentially sexual energies in the child himself? Is this narrative replete with the kind of "erotic horror" that Freudian critics like Mark Spilka find in James's tale (see Spilka's "Turning the Freudian Screw," rpt. in Kimbrough 249)? Or is Agnes's violence neither more nor less than what she deemed necessary for managing a difficult child on her own? In Agnes Grey, such questions would seem rhetorical. Still, the fact remains that, denied more acceptable means of exercising her authority by her anomalous rank, the young woman handles not only Tom but also his sister surprisingly roughly.

Edmund Dulac's illustration of Agnes Grey brushing Mary Ann's hair: "The dressing of Mary Ann was no light matter" (facing p. 408; by kind permission of Library Thing).

Agnes's "flights" are now limited to her "great joy" (414) when Tom sometimes finishes his schoolroom tasks obediently. In the main, however, from thoughts of watching "buds unfolding," she comes to this severe reflection on six-year-old Mary Ann Bloomfield's obstinacy: "I thought it my absolute duty to crush this vicious tendency in the bud" (415). The word "crush" is again indicative of violence, as, to a lesser extent, is her intention to use "unremitting firmness" to make the children "more humanised" (418). Such fierce determination obviously anticipates that of James's governess, to rescue Flora and Miles from the forces of evil: "Dear little Miles, dear little Miles," the later heroine repeats, "if you only knew how I want to help you! I just want you to help me save you!" (65).

At first reading, this is where the parallels between the two works end. Behind the Bloomfield children stand, not "dead servants" or "spooks" like Peter Quint and Miss Jessel (James's own words in his correspondence, rpt. in Kimbrough 108, 111), but flesh-and-blood examples of depravity. Admittedly, Agnes's aunt had described the Bloomfield children's mother herself as "a very nice woman" (401). It might be suggested that Agnes's very different view of her indicates the kind of unreliability in the narrator that some critics find in "The Turn of the Screw." But it is hardly likely that Agnes's descriptions amount to a gross misrepresentation, for while there is no independent observer to corroborate these descriptions, the adult Bloomfields' own words and actions weigh heavily and unequivocally against them. In particular, there is the children's coarse, brutal uncle, Mr Robson. Agnes notices his bad influence in "encouraging all their evil propensities" (426), and the ugliest episode in the narrative is not nursery mayhem, bad though that is, but the result of this uncle's presenting Tom with a nest of fledglings. There is not the shadow of a doubt that the birds are for Tom to torture, for there is not, by this stage, any of that teasing ambiguity about the boy which we continue to find in James's little hero.

Yet even here the two narratives have not diverged as much as it would seem. Agnes Grey knows too what the baby birds' fate will be; but, in order to distract Tom, she asks him what he means to do with them. The boy begins to list his projected tortures with "fiendish glee" (428). There is then some significant ambiguity about the governess's action, if not about her intentions. To save the helpless creatures from their fate, Agnes drops a large stone on the nest and kills them outright. She sees this action as nothing but her plain duty, and confidently presents it to the reader as such. But "Uncle Robson" is not angry, as Tom had said he would be. Rather, he is hugely amused by the unexpected violence. "Well, you are a good 'un!" he exclaims, "honouring" Agnes with "a broad stare" (428-29). In this way, Agnes seems temporarily to have put herself on a level with the man who has just been seen kicking his dog. Mrs Bloomfield is mainly angry with Agnes for coming between Tom and his pleasures, but this Victorian matron does show a flash of more conventional feelings: surely she would not have been alone in finding this "wholesale" murder "shocking" (429) — the more so in an age when heroines like Dickens's Little Nell dote on their pet birds. (Indeed, in Chapter 1, Agnes herself had taken a tender farewell of her favourite tame pigeons before leaving home for Wellwood.) Although one hesitates to talk of parallels when comparing small birds to a boy, this culmination of the governess's physical violence, sacrificing the most vulnerable of lives in the battle against corruption, might be said to foreshadow or perhaps even to have given James the hint for the tragic ending of "The Turn of the Screw."

Anne Brontë herself does not continue in this vein. Soon after the incident in Agnes Grey, the governess, now being blamed for a lack of "sufficient firmness" (431), is dismissed from her post at Wellwood. The break probably reflects the stages of her author's own governessing career; yet it also seems, from the discussions that occur in Chapter 6, that she felt the need to stop and reflect at this point.

The breathing-space brings Agnes some useful reassurance, but also leads to or possibly endorses a modification of her behaviour. As previously noted, like James's governess, she comes from a parsonage. The attitude of her eminently sensible mother, on her return, confirms that she has acted, according to the lights of her times, conscientiously. The doctrine of original sin is accepted: not even Agnes and her sister had been "perfect angels," says this wise matron. On the other hand, the sterner doctrine of the elect is set aside in one significant exchange between Mrs Grey and her husband: having pulled him up sharply for bewailing their poverty, "I won't bear with you," she says, "if I can alter you." The suggestion is, of course, that faults can (and in view of Mrs Grey's obvious in orthiness) should be worked on and perhaps cured. As for the Bloomfield children themselves, Mrs Grey does not say that they are beyond redemption, only that stone is not "as pliable as clay" (433). By the continual action of water, an impression can indeed be made on stone, and we might recall that Agnes had begun to feel that she was making some headway with these spoiled children just before her dismissal. For example, she "had at length brought them to be a little — a very little — more rational about getting their lessons done in time to leave some space for recreation" (430). Nor had Agnes, herself, wished to terminate her employment at Wellwood. Thus the verdict from this domestic interlude must be that, confronted with "the old Adam" in that apparently intractable brood, in her first post Agnes was quite right to have done what she could to drive out sin and educate the children's souls for heaven; but, on the other hand, there is also a hint that milder measures would eventually produce results.

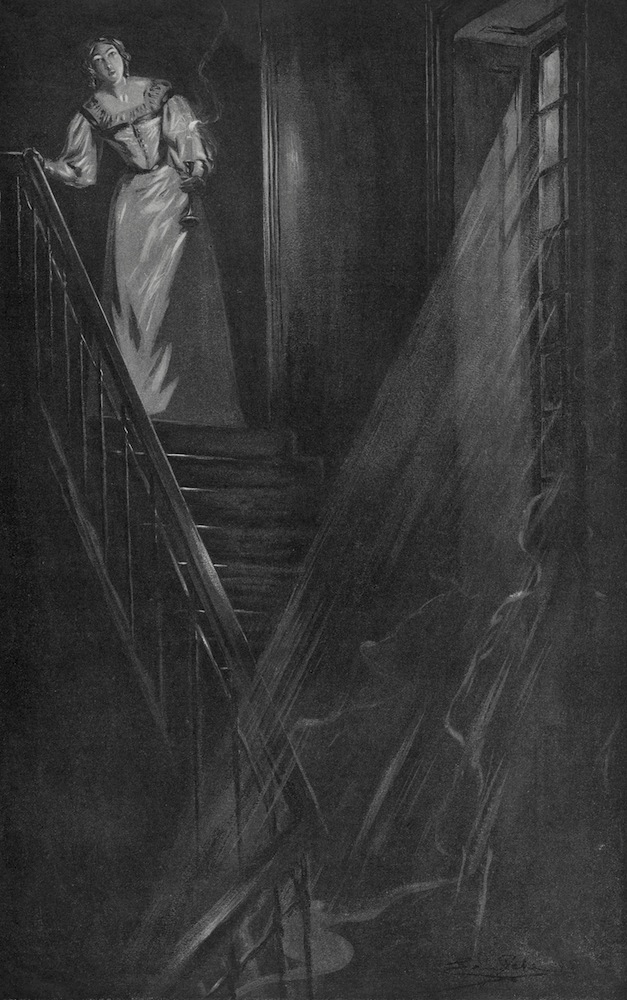

Eric Pape's illustration of James's governess seeing the ghost of Peter Quint for the third time: "Holding my candle high, I came within sight of the tall window." Source: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

From this point, the two narratives do diverge. Agnes modifies her behaviour towards her next band of unruly charges; James's governess, on the other hand, haunted by the ghosts of Quint and her own predecessor, meets the disappearance of "childish beauty" (78) with more and more frantic efforts to restore it.

In her next post, Agnes Grey's charges are no better-natured, but the two girls she has to deal with for the longest period (their brothers having, in due course, been sent off to school), are older, and there is no mention or question of force. She never shakes them or pulls their hair, as she sometimes used to shake five-year-old Mary Ann Bloomfield, and pull her plaits. Indeed, Agnes sees herself through the Miss Murrays' eyes as "very obliging, quiet, and peaceable in the main" (448). This could, of course, be due to the pressure to succeed after her first dismissal. Agnes had certainly made it clear that she was "unwilling to be baulked again" (435). Moreover, it is true that her outward manner cloaks considerable unease and resentment. Along with her steady good principles, however, this temperate manner does eventually earn her the respect of both girls, and she for her part comes to pity Rosalie Murray when her marriage to a wealthy aristocrat fails to bring her any happiness. The girls never become more likeable in themselves, but there is just a hint of long-terrn benefit to them in Rosalie's remark that "all the wisdom and goodness" which Agnes has been trying to impart to her might "fructify" if she were older (538).

For James's governess, on the other hand, the battle intensifies: "It was like fighting with a demon for a human soul," she recalls, as she describes hiding the apparition of Peter Quint from Miles in the final chapter. Clearly, there is a particular urgency in the struggle over the boy, as if the child not only has a soul to be preserved, but epitomizes the soul itself: "and when I had fairly so appraised it I saw how the human soul — held out, in the tremor of my hands, at arm's length — had a perfect dew of sweat on a lovely childish forehead"(91). In fact. Miles is as representative in his own way as the governess is in hers, if not more so. In her relation to him, Agnes Grey's successor is the Victorian governess or the Victorian adult, and only by extension the repressive adult of any age; that is, she must be lifted out of her context a little before she can be discussed in such a way. But Miles is a child, whose potential for innocence does not attach to his individual circumstances. The prime target of his governess's assault on evil, Miles moves in stages from "the ravage of uneasiness" (91), to a feverish condition with its usual physical signs (pallor, and the sweat on his brow which the governess notices), to "convulsed supplication" (94) and finally death. No wonder there is "desolation" in the process of Miles's "surrender," and that, looking back, the governess allows herself to reflect, "I ought to have left it there. But I was infatuated — I was blind with victory" (92). Many Victorians, including both social reformers and men of letters (vide Forster's well-known advice to Dickens about Little Nell, and Dickens's acceptance of it) felt that there is ultimately only one way to preserve innocence in the young: they must be removed from the contamination of this world. Miles, like certain other children in their fiction, must die. The difference here is that the instrument of death is actually the child's own protector, and death comes not through illness or accident, but through the very pressure she exerts on him: as she says in the penultimate sentence of her narrative, "I caught him, yes, I held him — it may be imagined with what a passion...."

The governess's own doubts are significant, and it must be remembered that she too makes a far better hand of it in a later post. After all, we first hear about her in the frame story, as the governess of the first narrator's friend's sister, described by him many years later as "a most charming person — the most agreeable woman I have ever known in her position" (5) — a very far cry indeed from the troubled and overwrought creature of the main story.

Related Material

- 1. Realism and its subversion

- 2. Confronting the challenge

- 4. Precepts and prospects: The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, What Maisie Knew — and our own age

- The Victorian Governess Novel: Characteristics of the Genre

- The Victorian Governess Novel

- The Victorian Governess: A Bibliography

Bibliography

Brontë, Anne. Agnes Grey, in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Agnes Grey. London: Dent, 1922. [All page references to these novels are to this edition.]

"Group Read: Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë." [Illustration source.] Library Thing. Web. 15 May 2018.

James, Henry. "The Turn of the Screw": An Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Sources. Essays in Criticism. Ed. Robert Kimbrough. New York: Norton, 1966. [All page references to the story are to this edition.]

_____. "The Turn of the Screw." [Illustration source only.] Collier's Weekly. Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Kimbrough, ed. "The Turn of the Screw": An Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Sources. Essays in Criticism. By Henry James. New York: Norton, 1966.

Created 13 May 2018