So intensely had the money-getting passion taken possession of the national mind — so associated had national prosperity seemed to be with individual wealth — that nothing appeared great, noble, or desirable but gold, and the standard of material value was constituted to be the standard of all moral excellence: intending to honour Industry, the nation had paid its homage to Money! [Chapter LXXVIII, "The Train," p. 683]

Although Charles Lever pointedly refers immediately after this analysis of Dunn as the personification of British greed to "all the victims to Dunn's perfidy," today's reader, far removed from the financial bubble of the 1850s, is struck by the Anglo-Irish novelist's ambivalence about the Irish "straw man," financial wizard and cagey politician Davenport Dunn, whom Lever based loosely on an actual swindler, the money-man John Sadleir. Lever acknowledges that his valiant capitalist leverages investments and manipules investors, but seems proud of Dunn's meteoric rise from Irish peasant to international power-broker ‐ and never completely justifies the reader's regarding Dunn as just another white-collar criminal, so vast and even epic has Dunn's "scheme of ruin" (682) proven at all levels of British society. As George Robb explains of Sadleir's Irish bank frauds in White-Collar Crime in Modern England (2002),

The nation was shocked . . .by the exposure of John Sadleir's frauds at the Tipperary Joint-Stock Bank. As director of the bank, Sadleir had embezzled some £200,000. Another £400,000 was lost when the bank suspended payment. Sadleir had come to London in 1846 as an agent for Irish railway schemes. Augmenting his directorship of the Tipperary Bank, Sadleir became chairman of the London and County Bank and the Royal Swedish Railway. Elected to Parliament he was a spokesman for business interests and was eventually appointed a Lord of the Treasury. As it later transpired, Sadleir had built his vaunted financial reputation on a series of monstrous impostures. Besides his embezzlements from the Tipperary Bank, he issued fictitious shares in the Swedish Railway to the extent of £150,000. While a member of the Irish Encumbered Estates Commission Sadleir also forged title deeds to a number of properties. Rumours of his misfeasance had forced his resignation from the Treasury and the London and County Bank, and the crash of the Tipperary Bank in January of 1856 laid bare his crimes. Sadleir immediately committed suicide, inspiring Dickens to create the character of Mr. Merdle [in Little Dorrit].

On the very heels of Sadleir's demise, the Royal British Bank failed amid revelations that the bank manager, Hugh Cameron, and two directors, Humphrey Brown and Edward Esdaile, had wasted the bank’s resources in unsecured loans to themselves and their friends. [62]

Lever, perhaps with a tinge of national pride, could not bring himself to have his titular hero commit suicide in a public park as an easy way out of cheating the law once the authorities discovered his financial crimes and exposed his fraudulent investment practices. Rather, Lever has the ruthless Christopher ('Grog') Davis, a gambler and sharper, kill Dunn in self-defence in a surprising turn of events late in the story. In Chapter LXXVII, the third to the last (entitled "The Train"), Davis breaks into Dunn's private club-car and attempts to rob Dunn of documents that Davis mistakenly believes support Charles Conway's claim that by genealogical right he and not Annesley Beecher, now Davis's son-in-law, should enjoy the title and estates of Viscount Lord Lackington.

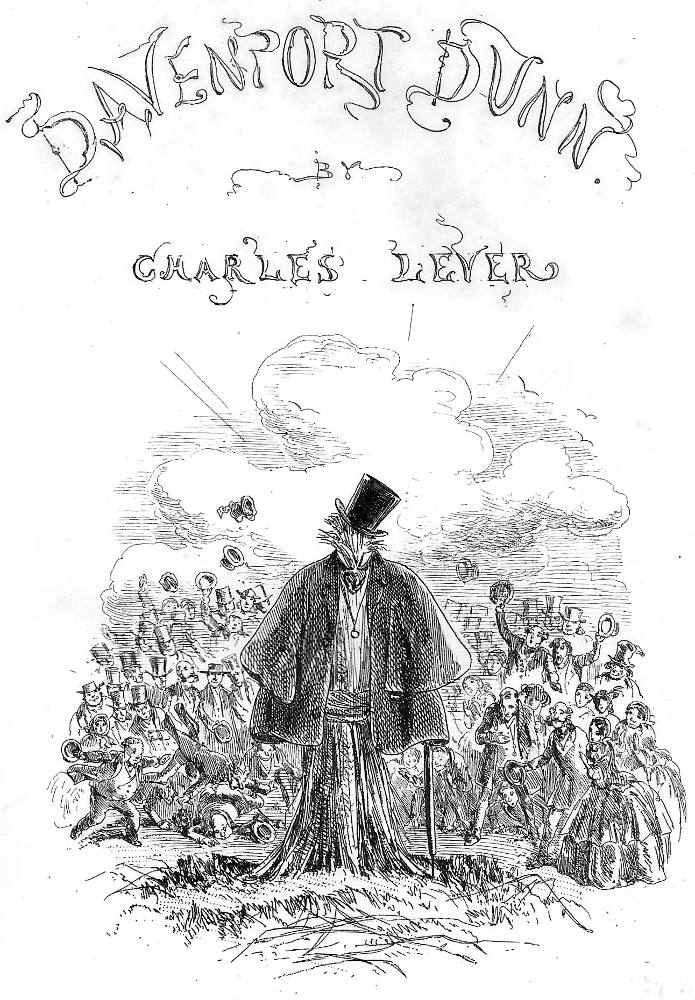

What, then, are we of make of the jubilant response of the scores of ordinary people in the background in Phiz's engraved April 1859 title-page to the novel? The passage "Of the vast numbers who had dealings with him, scarcely any escaped: false title-deeds, counterfeited shares, forged scrip abounded" should suggest anything but unfettered adoration. However, as in the case of Dunn's Glengariff land development scheme, the average investor has regarded Dunn's rising from the peasant class to the upper echelons of British society as representing the triumph of the common man, and the common Irishman over the economically and politically superior English in particular. Through the Phiz plate Lever seems to be suggesting the response of the vast British middle class to Dunn's financial triumphs before his murder and the revellation of his chicanery. The textual referrent for depicting Dunn as a scarecrow or "man of straw" is absent, but it seems unlikely that the illustrator would have produced so conspicuous an interpretation of the eponymous hero without the author's endorsement. Curiously, in the novel Lever never once shows the somewhat puritanical Dunn actually enjoying his ill-gotten gains; for Lever's protagonist, the challenge of politics and the the money market matters far more than material gain.

Related Material: Financial Scandals

- The “Stain Cast upon Our Age and Our Civilization:” The Harm Davenport Dunn did to Britain

- Real and Fictional Swindlers of the 1850s: Sadleir, Merdle, and Dunn

- John Sadleir

- George Hudson

References

Browne, John Buchanan. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. New York: Charles Scribner's, 1978.

Fitzpatrick, W. J. The Life of Charles Lever. London: Downey, 1901.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

Robb, George. White-Collar Crime in Modern England: Financial Fraud and Financial Fraud and Business Morality, 1845-1929. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2002.

Stevenson, Lionel. Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. New York: Russell & Russell, 1939, rpt. 1969.

Sutherland, John. "Davenport Dunn." The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford U. P., 1989. Page 172.

Last modified 12 December 2019