Oliphant's discussion of Macaulay appears in the chapter entitled "Of Thomas Babington Macaulay, and of Other Historians and Biographers in the Early Part of the Reign" from her The Victorian Age of English Literature (1892). The following text, which George P. Landow scanned and translated into html, may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose; an acknowledgment to the Victorian Web would be appreciated. Oliphant employs brief sidebar comments in the margins of each page, sometimes as many as five, and I have used these comments as subtitles and broken some of her multi-page paragraphs into shorter sections. Some illlustrations have been added: click on these images to enlarge them.

Contrast between Carlyle and Macaulay

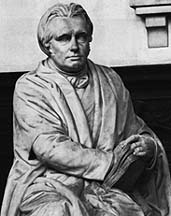

Thomas Babington Macaulay by Thomas Woolner.

IT is hard to conceive a stronger contrast to the rugged and imposing figure of Carlyle than is presented by the other brilliant prose writer whose fame was already becoming known far and wide at her Majesty's accession, chiefly through his political work. In appearance, as in mind, in thought, purpose, and style, they are as far apart as the two poles. It would be extremely difficult to make anything like a heroic figure of Macaulay, or to surround him with even pseudo-romantic attributes; and, fortunately for him, it would be quite impossible for the most indiscreet admirer to give any but a pleasant picture of his domestic relations. He is perhaps to some people the less interesting for being a model of the domestic virtues; indeed, an eminent writer or the present day has expressed his opinion that he was too good for any possibility of greatness. In thought lay perhaps the greatest difference of all. Not that Macaulay was disinclined to hero-worship of a kind, though the characters he would have selected for that cult would scarcely have been Carlyle's favourites, but in every other respect their methods of thought were as different as Macaulay's polished sentences are opposed to the dithyrambic utterances of the prophet of Chelsea. Metaphysics Macaulay loathed; and, though there might be some sympathy between him and Carlyle in their common delight in history, their predilection was prompted by entirely different aims and worked out entirely different effects.

Macaulay's Love of History

Macaulay loved history, as one loves Shakespeare; it was to him, in the first and highest respect, an unending series of scenes enacted by really living personages with whom he sympathised or differed as he might have done with his personal friends or the political characters of his day. The great charm to him was in the story, a story of matchless interest and eternal freshness from the thousand various lights in which it might be studied, not an elaborate lesson on profound philosophical truths delivered ex cathedra Natures. And if he drew lessons for the day from his historical studies, they were not concerned with abstract principles, with the cruelty and foolishness of one half of the human race or the subjection and misery of the other, or with elementary truths which might have attracted attention "at the court of Nimrod or Chedorlaomer," but were rather received as practical teaching of political justice and expediency such as might besuited to the most modern questions.

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1800-1857 [biographical information]

Thomas Babington Macaulay was born at Rothley Temple in Leicestershire in the year 1800. His father, Zachary Macaulay, was an ardent abolitionist, and secretary to the company formed by that party for establishing colonies of emancipated negroes on the west coast of Africa. Of Tom Macaulay's childhood many curious stories are told, — of the precocious learning with which he not only undertook but carried out a "Compendium of Universal History," which in his mother's opinion gave "a tolerably connected view of the leading events from the Creation to the present time," — of his poem in the style of the "Lay of the Last Minstrel," — his hymns, which gained the approbation of no less a person than Mrs. Hannah More, and his odd sententious speech. He was educated originally at a small school at Little Shelford, near Cambridge, and afterwards at Trinity College, Cambridge. While at the university he distinguished himself as a speaker at the Union and also by his contributions to Charles Knight's "Quarterly," started about this time with Praed, Macaulay, Moultrie, Walker, and the Coleridges, as its principal contributors. This small periodical excited a good deal of kindly notice, and was favourably mentioned by Christopher North in the "Noctes" as a "gentlemanly miscellany, got together by a clan of young scholars, who look upon the world with a cheerful eye, and all its on-goings with a spirit of hopeful kindness." Among Macaulay's contributions were his well-known poem of "Ivry" and many other pieces of verse, including some amatory lines in the first number which so shocked his father — who fortunately for Tom was unaware of the authorship — that lie forbade him to have anything; more to do with:1; publication. Fortunately, the decorous dulness of some succeeding numbers appeased the parental wrath, and Macaulay was allowed to take up his pen again. His principal prose contribution was a "Conversation between Mr. Abraham Cowley and Mr. John Milton touching; tin." '-^iit Civil War," of which the author himself thought highly, and 'not without reason. The "Quarterly Magazine" did not have a very long existence, coming to an end in its second year, owing to disputes among the contributors.

Restores the Family Fortunes

Meanwhile Zachary Macaulay, who had set up in business with his brother-in-law, Thomas Babington, as an African merchant, had met with reverses, his mind being too much occupied by the anti-slavery cause to pay a due attention to business, and his partner being hardly equal to the conduct of affairs of such magnitude. When Tom Macaulay left college, he found his father practically ruined, and accepted the situation with perfect calmness and the determination to set matters right again by his own exertions, which, impossible as it seemed, he managed to achieve in a few years with the help of his brother Henry. His support of his family, however, was not limited to material services of this description; the charm of his presence among them seems to have done more than years of unselfish toil on their behalf could have effected to cheer and comfort their despondency. His attachment to his brothers and sisters, especially the latter, was devoted and reciprocal, and even the silent, austere father, broken down as he was by this last calamity, felt revived and encouraged by the presence of the son, who could talk politics with him over the breakfast table.

His personal appearance

A sketch given of him a short time before by his friend, Praed, may not be uninteresting. He is described as

"A short manly figure, marvellously upright, with a bad neckcloth, and one hand in his waistcoat pocket. Of regular beauty he had little to boast; but in faces where there is an expression of great power, or of great good humour, or both, you do not regret its absence."

The homely features are said, indeed, to have been so thoroughly lit up by anything that awoke his interest, especially by that enthusiasm of talk which was his chief delight, as to compensate the absence of natural beauty.

Called to the Bar; Macaulay becomes a contributor to the Edinburgh

To put himself in the way of doing something for himself and his family, Macaulay began to study for the bar, to which he was called in 1826. He was, however, perhaps more fitted to succeed in the world of literature, and, in this profession, an unexpected prospect now opened before him. A year or so before, Jeffrey had written to a friend in London to make inquiries concerning any clever young man of Whig principles who could be found to assist him, as all the young- men of Edinburgh were Tories. Macaulay was pitched upon as a likely contributor, and exerted himself to produce an article that would satisfy the dreaded editor of the " Edinburgh." The result was his essay on Milton, suggested by Charles Sumner's edition of the newly discovered treatise, "De Doctrina Christiana." We do not profess any particular admiration for this paper, which appears to us to be marked by a flashy and florid exuberance of diction which we are not accustomed to find in his "Essays," and a general air of immaturity not unnatural to his age, and perhaps increased by a measure of timidity in a young author approaching for the first time one of the great pachas of literature, though we admit that timidity was not an ordinary characteristic of Macaulay. The article, however, was received with immense applause on all sides, Jeffrey being particularly enthusiastic. "I cannot conceive," he wrote to Macaulay, "where you picked up that style."

The profession of literature now open to Macaulay

The path of literature was now open to Macaulay, but it can hardly be said that he followed it with great success for the next year or two. With the temerity of an untried writer, he sought someone to attack whom wiser men than he admired. The Utilitarian school of philosophy offered a conspicuous and easy mark, and against this he directed the whole force of his pen in a series of articles which he afterwards regarded with a certain shame and refused to republish. The objectionable philosophy including in his mind the philosophers, he delivered a similar onslaught against James Mill's "History of British India," for which, in the preface to his collected "Essays," he afterwards made a manly apology, Congratulating himself on the fact which he insisted "ought to be known, that Mr. Mill had the generosity, not only to forgive, but to forget the unbecoming acrimony with which he had been assailed, and was, when his valuable life closed, on terms of cordial friendship with his assailant."

Narrowness and prejudice against political adversaries

Indeed Macaulay, though not a malevolent, or even a naturally uncharitable man, was too ready to form an unkindly judgment of his political adversaries. The opinion of Sir Walter Scott, expressed by him in a letter to Macvey Napier, astounds us by its narrowness and prejudice, and we are certain that if anyone had told him that his constant opponent, Crocker, had any one good quality in his composition, honest, kind-hearted Macaulay would have been quite unable to believe it. To the enemy who made amends he could, indeed, be reconciled. His fury at the attacks made upon him in "Blackwood" expressed itself in a studied affectation of scorn and that rueful laugh which described in unclassical English as proceeding from s wrong side of the mouth; but when his old enemy, Wilson, to whom such magnanimity was no effort, gave unmingled praise to the "Lays of Ancient Rome," Macaulay was most anxious that he should be assured of the author's appreciation of the criticism. However, Macaulay's polemics were not his only, nor his best, work in the first few years of his writing for the "Edinburgh." In 1827 appeared his masterly study of Machiavelli, perhaps chiefly remembered for the" almost casuistical ingenuity of his apology for that great writer's cynical theories regarding treachery and assassination. The following year was marked by his admirable essay on Hallam's "Constitutional History."

[Macaulay's political career begins:] Enters Parliament as member for Calne, 1830

In the good old days of patronage, literary merit had fifty times the chance of recognition that it can possibly have now, and Macaulay was not long in receiving a substantial token of the admiration felt for his genius. In 1828 the Lord Chancellor, Lord Lyndhurst, appointed him to a Commissionership of Bankruptcy. Two years later Lord Lansdowne, having a pocket borough to bestow, thought it could not be better represented than by this clever young literary man, who accordingly entered Parliament as member for Calne in 1830. His first speech in the House of Commons, on the question of Reform, established his fame as a parliamentary orator. Perhaps the greatest tribute to the position which he at once acquired in the House was the fact that no speech of Macaulay's was allowed to pass without an answer, a leading debater of the Opposition always rising to reply when he sat down. A bill was I brought in about this time to reform the Bankruptcy system, which, among other changes, destroyed the small office held by Macaulay; he however voted for the bill, which was passed.

Appointed to the Supreme Council for India

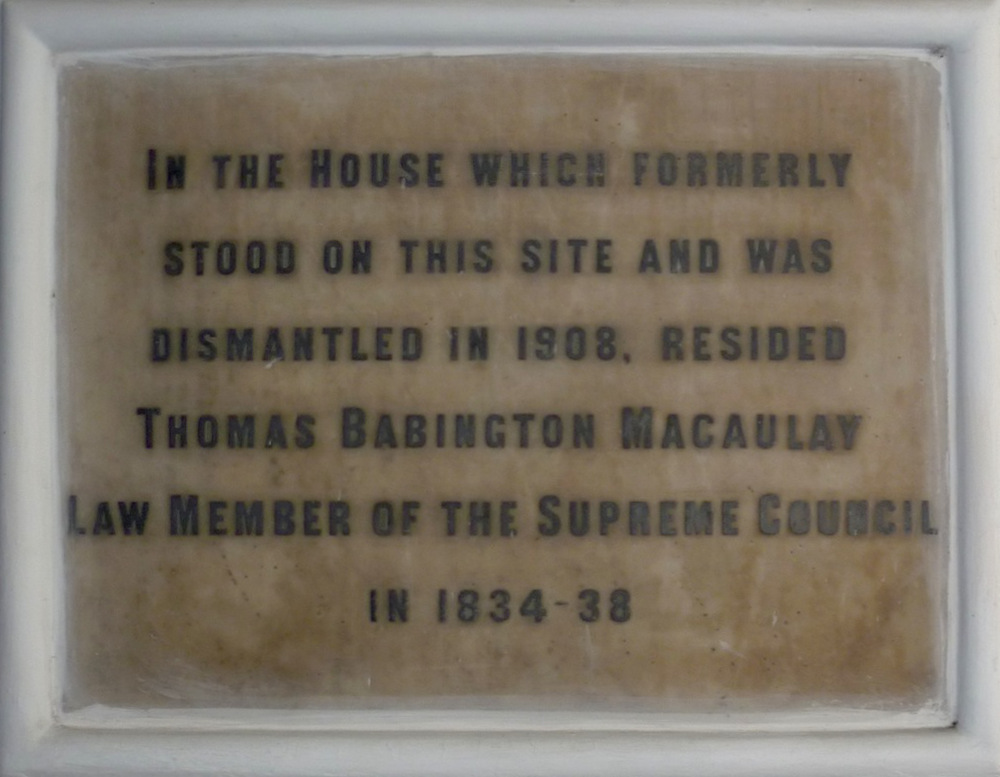

Plaque in Chowringhee, Kolkata. Photo: JB

In 1832 he was appointed Secretary to the East Indian Board of Control, and two years later was offered a post on the Supreme Council for India, with a large salary, which, though he had just been returned to the reformed Parliament for the new constituency of Leeds, he did not feel justified in refusing. He therefore sailed for India in 1834 and remained there for four years. His chief work while in Calcutta was done as President of the Committee of Public Instruction, and of the committee which was appointed to draw up a Penal Code, and a Code of Criminal Procedure. The former code, in the preparation of which he took much the greatest share, though it is now believed that his colleagues, especially Sir John Macleod, rendered him considerable assistance, is one of his most enduring titles to fame. During the period of his expatriation, he continued to contribute to the "Edinburgh Review " the essays upon Sir James Mackintosh's "History of the Revolution," and upon Lord Bacon.

Return from India, 1838

A great grief awaited Macaulay when he returned home full of joy and hope to those whom he had left behind. The household had been a sad one in his absence. "It is as if the sun had deserted the earth," wrote one of his sisters, while he was away; and Macaulay himself felt the separation as keenly, though his incessant toil in India was on behalf of those he loved, to restore the fallen fortunes of his family. As soon as he had conquered in his struggle to attain this end, he returned to England with "a small independence, but still an independence;" but the home he arrived at was a house of mourning. Worn out in mind and body, with the bitter feeling to one who had been a man of action, of helplessness and dependence, even on his own son, allying itself with his bodily ailments, Zachary Macaulay had died about a month before his son's return. It was, perhaps, to distract his mind from this sorrow that Macaulay, after a few weeks' stay in England, during which he dashed off one of his most brilliant essays, that on Sir William Temple, for the "Edinburgh," betook himself to Italy, where he remained for some months. On his return, early in 1839, he at once devoted himself to his work with renewed energy. His first duty was to the "Edinburgh," for which he wrote a trenchant, yet not unkindly, criticism of a somewhat reactionary treatise on the relations of church and State, by "A young man of unblemished character and of distinguished Parliamentary talents, the rising hope of the stern, unbending Tories," — the young member for Newark, William Ewart Gladstone. Macaulay speaks with some severity of the views expressed by Mr. Gladstone, but kindly of the young man himself; he was too good a judge of men to harbour any prejudice against the extreme views of youthful genius.

Appointed Secretary of War, 1837

In the same year, Macaulay was invited to stand for Edinburgh, and was returned practically without opposition. Lord Melbourne, the Prime Minister of the day, was glad to strengthen a fallen Government by the support of so brilliant a debater, and Macaulay was appointed Secretary of War, with a seat in the Cabinet. He held this appointment till the fall of the Ministry, two years later, after which time, with the exception of a short period in the years 1846-47, during which he was Paymaster-General under Lord John Russell's administration, he never again accepted office.

He plans a great historical work, of which only a part was finished

He continued in Parliament, however, and was still busy as a contributor to the "Edinburgh Review," but neither a political career nor periodical literature seemed to offer a sufficiently wide scope for his genius. He was anxious to achieve some really great literary work, and had already laid out the plan of a great historical book, extending from the reign of James II "down to the time which is within the memory of men still (1840) living." We all know that this great work was never finished, nor are we sure that it is to be greatly regretted. It has been calculated that if the whole period had been recorded with as much care and labour as Macaulay spent upon the fragment which he completed, the work could not have been in less than fifty volumes, which, at the rate of progress habitual to the writer, must have occupied a hundred and fifty years. The only chance of completing it would, therefore, have been by omitting the labour and research which made the work move slowly, and furnishing us with a hasty and superficial sketch of the whole, instead of the vivid and complete picture of a part which has been left to us. Such a consummation could not be desired by anyone.

The Lays of Ancient Rome

The "History," however, could not yet be got in hand. Macaulay's first production was the one which has, perhaps, made his name more widely known than any others, the "Lays of Ancient Rome." The chorus of enthusiastic applause with which the "Lays," were received — Macaulay's veteran adversary, Christopher North, shouting with the loudest, — has not, perhaps, been uniformly echoed by the critics of latter days; but with the far more important audience which lies outside the little circle of self-appointed judges, and accepts their judgments when it agrees with them, they have never lost their popularity. Every schoolboy knows them, to use a favourite phrase of Macaulay's own, though schoolboys are not usually partial to poetry, — but to the minstrelsy of Scott or Macaulay — it is much to mention them together — no healthy-minded boy refuses to listen; nor should we think much for the boy who could not declaim some of the fiery sentences of Icilius, or describe exactly the manner of death of Ocnus or Aruns, Seius or Lausulus. Of older readers it is less necessary to speak, as he who has known Macaulay's Lays in his childhood has no occasion to refer to them again. There is an unfading charm in the swing and vigour of the lines which bring to our ears the very sounds of the battle, the clash of steel and the rushing of the horses, "the noise of the captains and the shouting." "A cut-and-thrust-style," Wilson called it, "without any flourish. Scott's style when his blood was up, and the first words came like a vanguard impatient for battle." The praise is scarcely extravagant.

Critical and Historical essays, 1843 — No other collection of this kind has ever equalled their popularity

At the same time Macaulay was hard at work collecting his various "Essays" for republication. He had not wished to do this, considering it unadvisable to tempt criticism with a volume of occasional papers, however successful they might have been in a magazine; but the importation of pirated American editions left him no choice, and the collection was published in 1843. It was received with enthusiasm and at once attained a popularity which it has never since lost, and which certainly no collection of the kind has ever equalled. There is some reason to doubt the expediency of republications of this description, though they are certainly the means of preserving the fame of a periodical writer for future generations; and there are perhaps few cases in which they have any chance of becoming popular. We are accustomed to find collected essays or articles among the collected works of every eminent modern writer, but the volumes which contain them are usually the least read. But Macaulay's Essays have achieved for themselves a position in popular literature as a work which everyone delights to read, not for conscience' sake or duty, but merely as a thing to be enjoyed, which it may well be said no other essayist has equalled. They are so well known that any kind of detailed criticism would be superfluous; nor, as everyone has his own favourites, would it be of any great use to make selections from among them. Yet we will own to caring least for those which deal with the political questions of the day and most for those of a historical, or still more biographical character. The ease and charm of the narrative in such favourite essays as those on Clive and Warren Hastings, cannot but be felt even by those who are most inclined to differ with Macaulay's estimate of his subjects. To us there is an even greater attraction in the light and yet elaborate studies of character as demonstrated in action, such as are contained in the papers upon Sir William Temple and on Addison, or in the more weighty essays upon the Earl of Chatham — brilliantly begun in comparatively early life, before the writer went to India, and continued ten years later with greater force and solidity of judgment towards the end of his career as a periodical writer, — to which a fitting complement may be added by the masterly biography of the younger Pitt supplied by Macaulay to the Encyclopaedia Britannica and reprinted with his other contributions on Atterbury, Bunyan, Goldsmith and Johnson, by Mr. Adam Black, the publisher, after the author's death.

Closes his connection with the Edinburgh Review. 1844

Macaulay was now becoming impatient of the various occupations which prevented him from getting to work on his long-projected history. In 1844 he definitely closed his connection with the "Edinburgh," which he had lately felt to be a great drag on him, having contributed only two more articles — those on Frederick the Great and Madame d'Arblay, respectively, — after the publication of the collected "Essays." All this time he was attending to his Parliamentary duties, and some of his most telling speeches were delivered in the Parliament of 1841-47. His appointment as Paymaster-General in 1846 obliged him to seek re-election at the hands of his constituents, and, though no longer unopposed, as in 1841, he was returned by a triumphant majority over his adversary, Sir Culling Eardley Smith.

Macaulay loses his seat in Parliament [because of his defense of Roman Catholic civil right]

Much sectarian opposition, however, had been excited against him by his action on the question of the grant to Maynooth College, and at the general election in 1847, to the lasting shame of the constituency, Macaulay lost his seat. Wilson, his old literary adversary and political opponent, had risen from a sick-bed to record his vote for the victim of what was generally felt to be an unjust persecution, and the public sympathy was freely expressed, but Macaulay himself apparently did not feel the loss. It gave him, at any rate, a great deal of additional leisure to devote to his "History" which was now so far advanced that the two first volumes were ready for publication in the ensuing year.

First two volumes of The History of England — Its success phenomenal

The success of the "History of England " from the first day of its appearance was phenomenal. A first edition of three thousand copies was exhausted in ten days, a second of the same size was entirely bought up by the time it appeared, and a third of five thousand was so nearly exhausted six weeks after the original issue, that it was found necessary to print two thousand additional copies to meet the immediate demand. The excitement aroused by its appearance may be to some extent estimated by the fact that the Society of Friends thought it necessary to send a deputation to remonstrate with Macaulay for the view he had taken of William Penn. The honest Quakers were no match for the brilliant dialectician, who successfully reasserted his views on the subject, but it has since been proved that they had the right on their side. Lockhart wrote to Croker, who was waiting to measure out to Macaulay such criticism as had been meted to his own edition of Boswell in days gone by, — that he had read the "History" through "with breathless interest," but admitted that it contained so many inaccuracies that the greatest injury would be done to the author's feelings by telling the simple truth about his book. Croker, however, wrote so savage a review that, in face of the general public approval, it hardly excited any notice at all, though his strictures were hardly more severe than the criticisms of many later writers. For the time, however, opposition was hopeless, and the chorus of approval was hardly broken by one dissentient voice. Macaulay himself told an amusing anecdote illustrating its popularity at the time. "At last," he wrote to his friend, T. F. Ellis: "I have attained true glory. As I walked through Fleet Street the day before yesterday, I saw a copy of Hume at a bookseller's window with the following label: 'Only /"2 2s. Hume's History of England in eight volumes, Highly valuable as an introduction to Macaulay!'"

The absolute continuity of the story and the masterly sketches of character

Whatever may be its value as a correct record of fact, Macaulay's "History" is certainly a very remarkable production of literary art. It is perhaps one of the greatest efforts in narrative that has ever been made. From beginning to end we have avast history — in the original sense of the word which we usually denote by lopping the first syllable — flowing on in a perfectly unbroken stream, the thousand little rivulets that converge into the main flood neither neglected nor magnified into undue importance, but firmly and skilfully guided into their proper places as the component parts of a great whole. Nothing is more striking- in Macaulay's work than this absolute continuity of story. There is no lack of adornment, of literary grace of style and picturesque detail, nor is there any point in which MacauLiy's genius is more amply displayed than in the masterly, if occasionally prejudiced, sketches of character with which the "History" is interspersed; but everything is subordinated to the central necessity of allowing no break or obstacle to the narrative. Thus we get those exquisite little portraits in miniature which Macaulay threw in with such wondrous skill when he had to present a new character upon the scene whose antecedents or peculiarities it was necessary to know, but whom there was no time to describe at length. Even the more finished and elaborate studies of individuals hardly distract the attention from the main story longer than it would take a reader to turn aside from the text of his book to look at a full page illustration; and these are only given when required as a foundation of knowledge on the subject, to give some idea what manner of man is presented before the audience; for as to the real character of each actor, he will soon show that in the only reliable manner, by his actions. Macaulay's enemies are accustomed to say that these characters are only drawn with exactitude when it suits his partisan purposes to make them true; otherwise they are exaggerated by partiality or discolored by prejudice, and the story of their lives is told in such a manner as accords with the political views of the writer. To our mind such charges are brought on too general a scale; but we are obliged to admit that in some cases they are not without foundation. We have already said that Macaulay often found it hard to do justice to his political adversaries, and we cannot contend that he was more impartial in the matter of statesmen of days long gone by, to whose' principles or conduct he was opposed. To him the men of the court of James II were as real and living as those among whom he lived; and among the former, as the latter, he supported his friends and attacked his enemies. He hated Malborough as he hated Croker; he spoke his hatred out, as was his nature, and he refused to see any redeeming points in the character of either adversary; we may say, indeed, that he was incapable of seeing them. We will not even deny that in the heat of his animosity he may have distorted facts; for every student of history knows with what readiness those elastic trifles will assume all varieties of shape according to the glasses through which they are observed. But these, at the worst, are in a few extreme instances, for which we at least are ready to forgive one of the only historians who has been able to make his readers live in the period of which he writes.

Macaulay's work like the unfolding of a drama before our eyes

Coloured as his narrative may be, it is yet history, and history of the most profitable kind. The lecture-dried student, whose interest in history only tends to the answering of questions at an examination, or at best to endowing posterity with a set of cut and dried, annals for the benefit of future candidates for honours, finds little use in Macaulay. He says both too much and too little, and is too entertaining for the conscientious reader to study in working hours. It is like Partridge's judgment on the theatre, when he preferred the king in Hamlet, who was so obviously acting a part, to the quiet, little man, Garrick, who spoke and moved as an ordinary mortal might have done. No one could possibly read one of Dr. Gardiner's valuable works without feeling that he was studying history; when we read Macaulay, on the other hand, we feel more like the spectators of a great natural drama unrolling itself before our eyes. We are not even hearing the story told by one of the actors, but actually looking on at what is taking place. This, is to our mind the great superiority of Macaulay's work over those of more exact historians. Perhaps we may take an illustration of our meaning. suppose that we wished to form a correct idea of St. Peter's at Rome or St. Mark's at Venice. There are numberless works in which we could find exactly measured designs of the plan, elevations and sections of the buildings, from which we might gain a great deal of practical knowledge and be able to impart it to others. But would anyone suggest that we should thus get anything like so real an idea of St. Peter's as could be derived from seeing one great picture of the whole, even if the artist had made the facade a yard too long or the cupola a couple of feet too high. So in Macaulay's great picture of the past, the reader can see at a glance more of the real life of the world as it was, than the most toilsome examinations of historical evidence can afford him. Not that we undervalue the latter. When the reader has taken in the sense and the story of the picture, by all means let him go and verify his measurements.

Raised to the peerage as Baron Macaulay of Rothley, 1857

Poet's Corner, Westminster Abbey.

There is not very much more of Macaulay's life to

record. The third and fourth volumes of the History

were published in 1855, and the fifth and last was

not finished at his death. It was a great disappointment to him to be unable to carry it further on, at

least to the reign of Anne. In 1853 he was induced

to make a collection of his speeches for reasons

similar to those which had led to the publication of

the Essays. His parliamentary duties were resumed

for a while, for Edinburgh had repented in sackcloth

and ashes, and, on the resignation of his old colleague, Sir William Gibson Craig, put him at the head

of the poll, though he was not able to be present to

conduct the contest in person. His health, however,

was failing, and, after being many times over-persuaded by his constituents, he insisted on resigning

his seat in 1856. The next year he was raised to

the peerage as Baron Macaulay of Rothley. He

still worked at his History in his latter years and contributed to the Encyclopaedia Britannica the articles

of which we have spoken. His last days were peaceful, though somewhat overclouded by melancholy,

and his end was peace itself, the gentle and easy

transition that comes to some who scarcely seem to

die but merely cease to breathe. Perhaps this was

the end of Enoch; Macaulay died in the last days of

the year 1857, and was buried in Westminster Abbey,

in Poet's Corner, at the feet of the statue of Addison.

![]()

References

Oliphant, Mrs. [Margaret]. The Victorian Age of English Literature . N.Y.: Dodd, Mead, 1892. 157-79

Last modified 28 December 2016