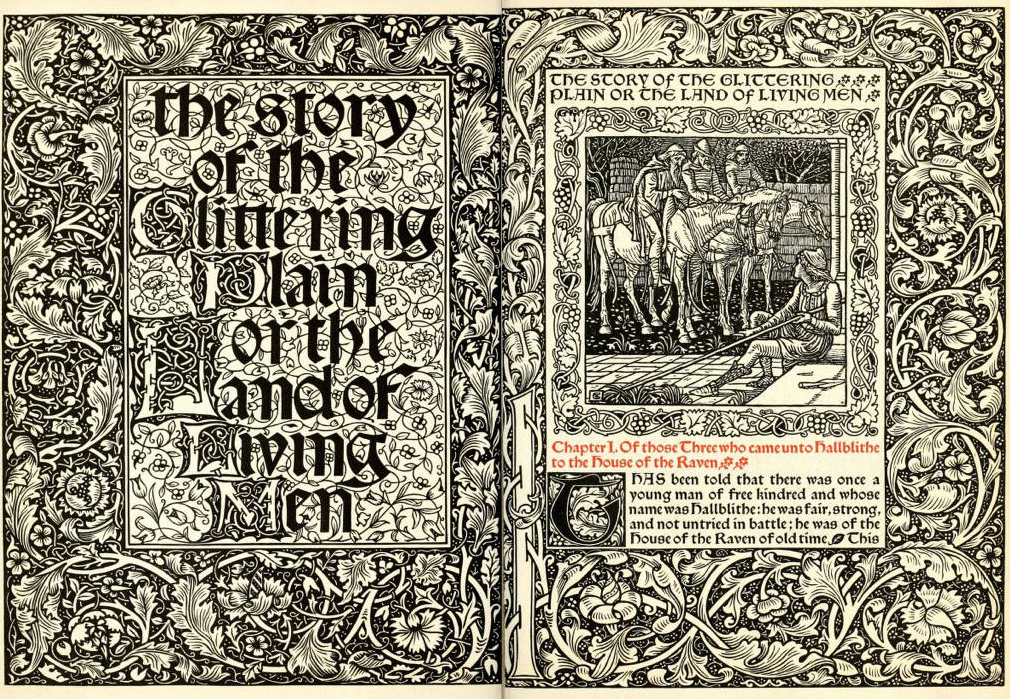

The Kelmscott Press was, in a very real sense, the final statement, the culmination, of the work of art which was Morris's life, as it was one of his final attempts to preserve the old relationships between the artist and his art and his society — threatened in his day as in our own — and one of his great legacies to posterity. In 1891 he rented a cottage near Kelmscott House and set up three printing presses . He had long been interested in the printing and the binding of fine books, and there, influenced by mediaeval illuminated manuscripts and the work of early printers such as Caxton, he would design and manufacture beautiful editions of over fifty books (printed in over 18,000 volumes) written by himself as well as by those — including Coleridge, Keats, Shelley, Tennyson, Rossetti, Swinburne, and his favorite mediaeval authors — who had influenced him, and to whom, in this series of final gestures, he paid a kind of tribute. The books issued by the Kelmscott Press were expensive — Morris designed his own typefaces, made his own paper, and printed by hand — but they were beautiful. They were designed to be read slowly, to be appreciated, to be treasured, and thus made an implicit statement about the ideal relationships which ought to exist between the reader, the text, and the author — a statement which we have, by and large, continued to ignore.

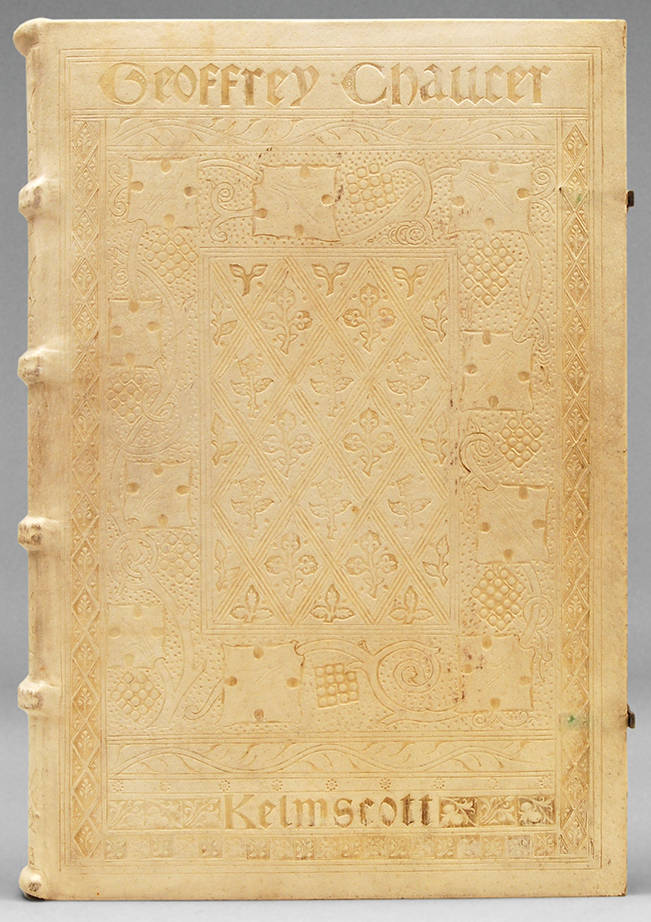

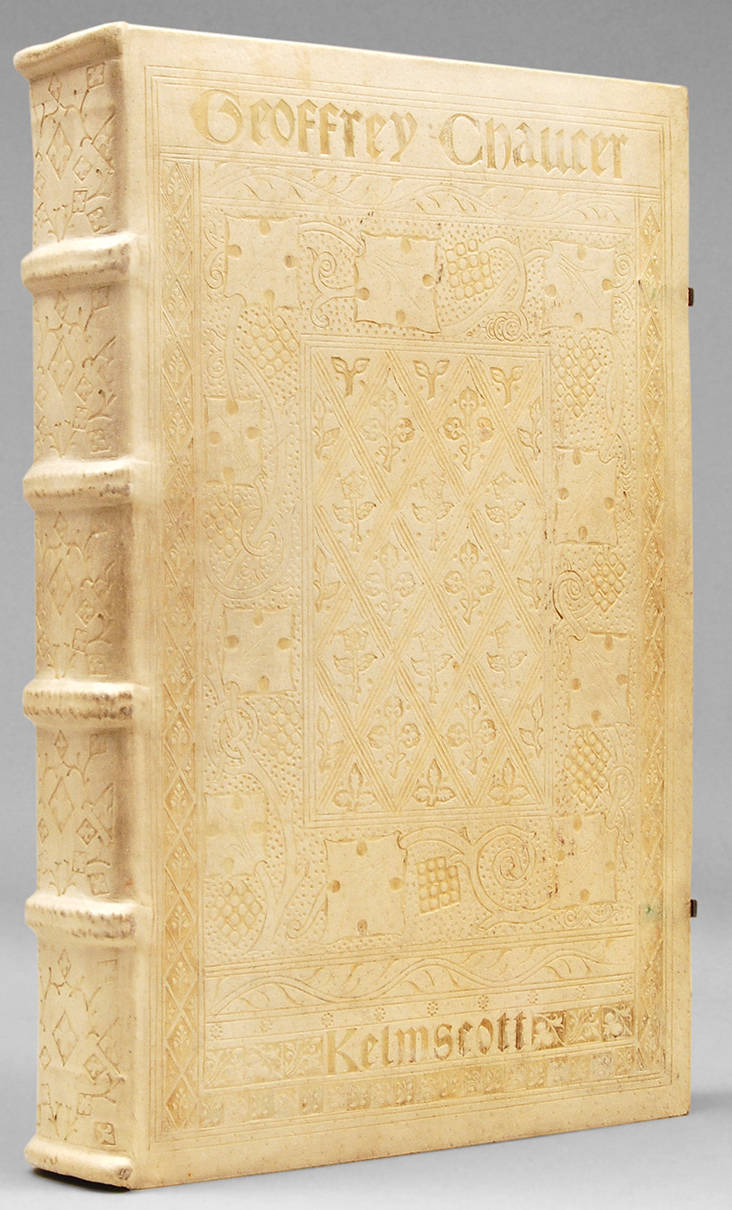

Left to right: Three views of the Kelmscott Chaucer. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

As Duncan Robinson points out,

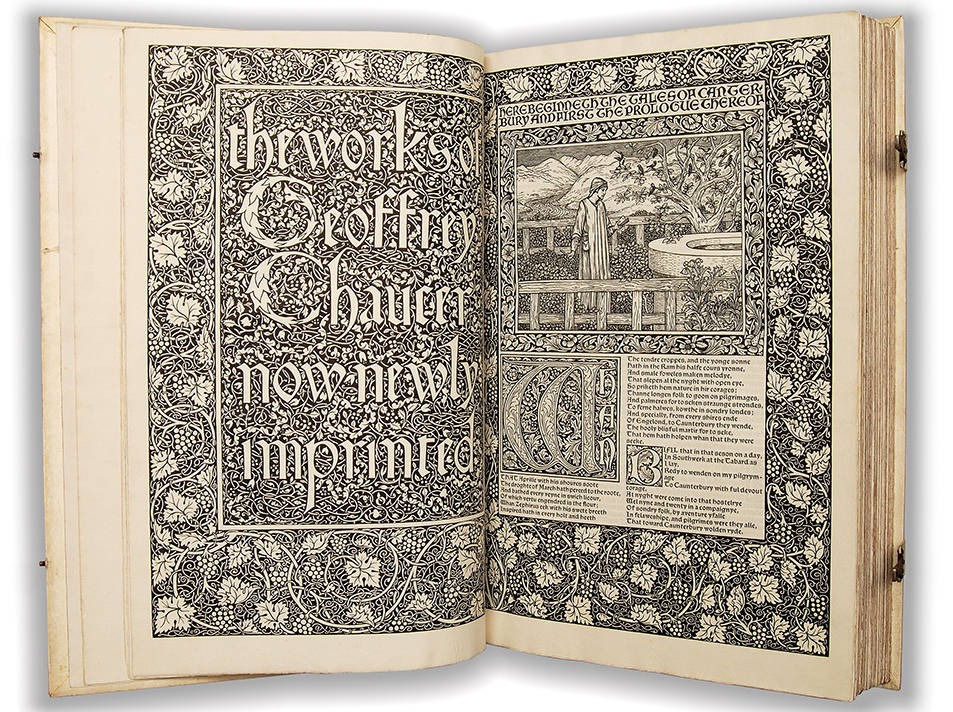

To the modern reader, accustomed to the functional sans-serif type faces of the twentieth century, Kelmscott publications have a decorative richness that places them squarely in the Victorian period. With their ornamental bindings, foliated borders and woodcut illustrations they have become prime examples of late nineteenth-century decorative art, from the hands of the man who made a greater contribution to that field than any other individual. But this should not be allowed to obscure the very clear emphasis that Morris placed, in stating his aims as a printer, upon clarity and simplicity. 'I began printing books', he wrote, 'with the hope of producing some which would have a definite claim to beauty, while at the same time they should be easy to read and should not dazzle the eye, or trouble the intellect of the reader by eccentricity of form in the letters.' [13]

The finest achievement of the Kelmscott Press — The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, designed by Morris and illustrated by his old friend Burne-Jones — appeared shortly before his death: the most beautiful book of its day, it serves as a fitting tribute both to Chaucer — his poetic "Master" — and to Morris himself.

Morris and Co, the catalogue of a 1979 exhibition at The Fine Art Society, describes the Kelmscott Chaucer and quotes Morris's credits:

Containing eighty-seven woodcut illustrations after Burne-Jones with title, borders and initials designed by William Morris. Printed in red and black on paper, bound in pigskin at the Doves Bindery, 1896. The Kelmscott Chaucer, the most famous of all Morris' printed works, occupied much of his time during the last six years of his life. It was the culmination of the artistic collaboration between Morris and Burne-Jones, which had spanned nearly forty years. Morris, in the penultimate paragraph, apportions the credits thus:

Here ends the Book of the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, edited by F. S. Ellis; ornamented with pictures designed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and engraved on wood by W. H. Hooper. Printed by me William Morris at the Kelmscott Press, Upper Mall, Hammersmith, in the County of Middlesex. Finished on the 8th day of May, 1896. [p. 55]

The edition on paper was limited to 425 copies. Folio

Related Material

- Morris's illuminations, printed books, and book design

- The Albion printing press, Hammersmith

- The Burne-Jones Illustrations for the Kelmscott Chaucer

- Morris and Chaucer

- Morris's Mediaevalism

References

Morris and Co. Exhibition catalogue. London: The Fine Art Society with Haslam & Whiteway Ltd., 1979.

Robinson, Duncan. William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, and The Kelmscott Chaucer. London: Gordon Fraser, 1982; Mt. Kisco, N.Y.: Moyer Bell, nd.

Last modified 6 November 2014