ere is a collection of academic essays assembled by the late

Frederick Nesta on publishing, bookselling, and readers in England and

elsewhere in the nineteenth century. The collection, titled rather

clunkily Where the Victorians Got Their Reading: Cultural Change in

Marketing, Distribution, and Individual Access for "The Million" in

Britain, North America, and Australia, contains material that allows the

reader to get a sense of the socio-economic and technological changes in

the Victorian era that transformed the book industry and provoked

opposition from traditionalists. The reader who navigates its sometimes

difficult prose will discover a world much like ours, in which

enthusiasm for the new ways collided with alarm at the consequences.

ere is a collection of academic essays assembled by the late

Frederick Nesta on publishing, bookselling, and readers in England and

elsewhere in the nineteenth century. The collection, titled rather

clunkily Where the Victorians Got Their Reading: Cultural Change in

Marketing, Distribution, and Individual Access for "The Million" in

Britain, North America, and Australia, contains material that allows the

reader to get a sense of the socio-economic and technological changes in

the Victorian era that transformed the book industry and provoked

opposition from traditionalists. The reader who navigates its sometimes

difficult prose will discover a world much like ours, in which

enthusiasm for the new ways collided with alarm at the consequences.

One of the most interesting essays in the book is Graham Law's contribution on "number men," that is, the door-to-door sellers of "number books," books sold in parts, notably encyclopedias and other reference works, but also Bibles, the works of Shakespeare, and novels. Door-to-door selling was a way to bring books to "the poor man's door," said one commentator at the time (89), though others denounced the practice as spreading cheap trash to the ignorant or as "one of the greatest nuisances of the day" (94). Some warned that the practice involved fraud and deception, and one offended cleric complained that a genteel young lady had intruded into his house to try to sell numbers of a new encyclopedia. This new custom, he said, threatened to add "a new terror to life" (93).

Throughout this book one can see the clash between new ways and old, between those who embraced new practices and those who clung to traditional ways and saw the innovations as dangerous. While new readers found new ways to acquire books — at the corner shop, the grocer's or the draper's, in addition to having them delivered to their door — those in the traditional book trade fumed, decrying the "orgy of underselling" (52) perpetrated by new discount publishers. One American bookseller warned that the book trade would soon be "in the hands of drapers, druggists, and grocers" (69).

But the changes could not be stopped. Thanks to growing prosperity and the Education Act of 1870, the market for books grew; people had money and they could read. Those who lacked money could go to libraries run by the Mechanics' Institutes, institutions devoted to the education of the working classes, where readers could find books on topics from phrenology to Fenimore Cooper. These institutions endured into the late nineteenth century, when they made way for free public libraries.

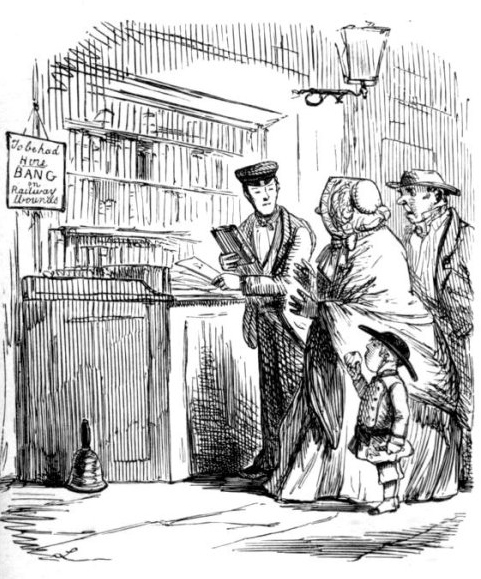

Included in this collection are two essays by John Spiers describing the spreading book market and warning against anti-business bias. It was the confluence of commercial, technological, and educational advances, he says, that produced both a large number of books and large numbers of people to read them. The railways played a key role here, as railway bookstalls run by W.H. Smith became ubiquitous. Books were sold not only at the stations but, at least in the United States, on trains themselves, as Anthony Trollope noted: he saw young tradesmen flinging books and magazines at passengers in the railway cars and coming back to collect their payment later (246-47, and see Trollope 1, 420-21).

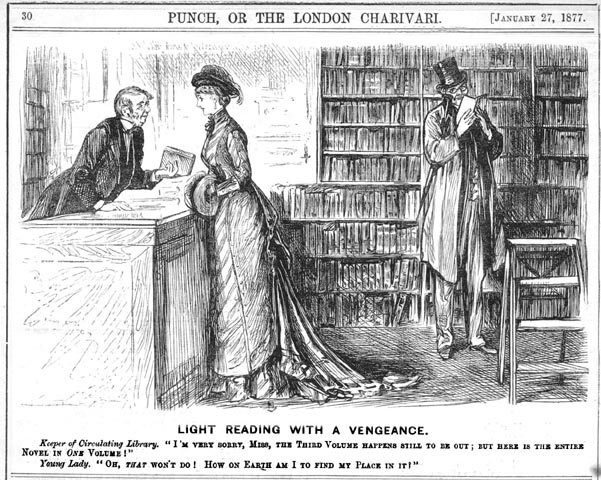

Left: "Railway Literature," engraving by John Leech; right: "Light Reading with a Vengeance" from Punch.

The traditional book trade fought a rearguard battle against these developments, but by the end of the century Mudie's traditional subscription library was gone, as were the three-decker novels that went with it. Some worried that this loss would sound the death knell for traditional bookshops as well, but what actually seemed to happen is that a new era of reading ushered forth in the form of cheap publications such as pocket novels and magazines like Tit-Bits. Books seemed to be everywhere.

This collection covers not just Britain but North America, and what emerges from this enlarged perspective are some interesting details about nineteenth-century reading sources. It might have been useful to have included a chronological essay tracing the developments, as well as a detailed description of a corner shop or a railway bookstall. But there are interesting morsels nonetheless, like the fact that a Dickens novel might be given away as a bonus for buying soap, or that in Victorian Ontario there might be household tensions over whether money should be spent on books or on necessities.

A little more class differentiation might have been useful as well. The book's subtitle suggests that the focus will be on "The Million," the mass market among the lower classes, but sometimes middle-class examples are included, creating some confusion. An article explaining how Mudie's worked for the upper classes might have clarified matters, along with more definitions: What exactly was a draper's shop? Was it for cloth or clothes or other things? Of course, the point that emerges here is that drapers diversified their products, leading to the development of department stores and to books being sold outside traditional bookshops. In response, the traditional bookshops branched out into stationery, purses, and umbrellas, prompting accusations and counter-accusations.

One of the remarkable aspects of the book is its favourable depiction of nineteenth-century capitalism. A couple of essays focus on radicals and criticize the authorities, but mostly the attitude is captured by Grace Adeneye in her essay on dime novels: "The lower classes called, capitalism answered" (237). Altogether the collection suggests that the spread of mass education caused an upsurge of reading, and the increased demand for books was met within an economic system that found ways to profit from the expanded market of readers.

Also of interest is Adeneye's distinction between the types of dime novels read by women and men. Women were drawn by the author's name, men by the hero's, perhaps because men were looking for a series of adventure books involving the same hero while women's novels typically ended with marriage, after which the heroine would not appear again. Another draw, as John Spiers notes, was the cover: the flashy yellowbacks were designed to capture travellers' attention at railway bookstalls.

Overall, what emerges from these essays is a picture of an age very much like our own, full of technological innovation and fears for the future. The book offers a sense of what it might have been like to seek out reading material in the nineteenth century while conveying the excitement, fascination, and concern about the spread of reading, reflecting the more general transformations of Victorian society. It is unfortunate that the picture is occasionally clouded by awkward writing, and the book is also marred by typographical errors, including one quite amusing one about the "daisy doses" of medication that Oscar Wilde was required to take while in prison (130). Still, there is much to gather here.

Links to Related Material

- Print and Print Culture in the Victorian Age

- Print Technology and Publishing: A Selective Chronology

- Pickwick Papers and the Development of Serial Fiction

Bibliography

[book under review] Nesta, Frederick, ed. Where the Victorians Got Their Reading: Cultural Change in Marketing, Distribution, and Individual Access for "The Million" in Britain, North America, and Australia. Brighton: Edward Everett Root, 2024.

Trollope, Anthony. North America. 2 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1862.

Created 9 October 2025

Last modified 6 November 2026