Where there are men and women in a society there will always be, to some extent, by some definition, prostitution; it is as an act old as time itself (indeed, there is evidence in the Code of Hammurabi of the Mesopotamian society to suggest that it existed in the eighteenth century BC). However, with its increasing number of social problems and rise in the middle class domestic morality it was the nineteenth century that saw prostitution become a social evil of epic proportions. In his 1862 publication, London Labour and the London Poor, Henry Mayhew mentions its origins in ”the year 1802, when immorality had spread more or less all over Europe, owing to the demoralizing effects of the French Revolution” (p. 211).

By the mid nineteenth century it was becoming more and more difficult for women to find work in more desirable professions, and this lead to a rise in the number of women holding jobs with long hours and little pay, such as agricultural gangs, shop girls, domestic servants, needle-trades and factory workers (Sigworth et. al, 81). Subsequently these women sought other means of supplementing their incomes, and increasingly turned to prostitution as a way to do so. With the passing of the Contagious Diseases Act of 1864, 1866 and 1869 (Acton, iii), which legalised prostitution but entailed legislation enabling the police to arrest women suspected of being prostitutes and the subsequent examination of them for signs of venereal disease, it became a matter of public controversy and the era of ”The Great Social Evil” was born. Mayhew discusses the definition of prostitution thusly:

Prostitution, professionally resorted to, belongs to the latter class [”obtaining a living by seducing the more industrious or thrifty to part with a portion of their gains”], and consists, when adopted as a means of subsistence without labour, in inducing others, by the performance of some immoral act, to render up a portion of their possessions. Literally construed, prostitutions is the putting of anything to a vile use . . . specially so called, is the using of her charms by a woman for immoral purposes. [4]

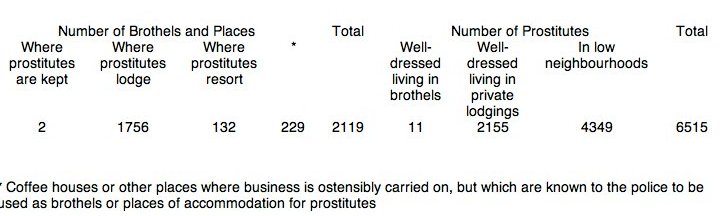

In Prostitution Considered in its Moral, Social, and Sanitary aspects (second ed. 1870) William Acton, M.R.C.S. attempted to give some estimate of the number of prostitutes in London at the time. These ranged from 6,371 as stated on the returns on the constabulary force presented to parliament in 1839, to an estimation by the Bishop of Exeter ”of them as reaching 80,000” (p.3). Through a series of calculations Acton bases on the statistics of births and marriages, he proposes that there are, in fact, many more: ”219,000, or one in twelve, of the unmarried females in the country above the age of puberty have strayed from the path of virtue.” In any case, prostitution was rapidly becoming prevalent in Victorian England, particularly in London.There were three very different categories pertaining to the housing of prostitutes, as defined by figures obtained by Acton from the Metropolitan Police Office in November of 1868 (p. 6). They were broken down as follows:

With the evolution of prostitution came a need for the evolution of its perception by society at large. ”The dirty, intoxicated slattern, in tawdry finery and an inch thick in paint — long a conventional symbol of prostitution”, Acton declares was not an apt depiction of a prostitute. According to him she was in fact ”generally pretty and elegant — often painted by Nature than by art” and had ”cast away the custom of drunkenness” (p. 27).

In his poem, “The Harlot’s House”(text), Oscar Wilde seemingly conforms to Acton’s supposition of the unsavoury stereotype:

Sometimes a horrible marionette

Came out, and smoked its cigarette

Upon the steps like a live thing.

It would appear that Wilde’s harlot falls into the category of whore living ”where prostitutes are kept”, defined by Acton as houses ”whose proprietors overtly devote their establishments to the lodging, and sometimes to the boarding, of prostitutes only”, otherwise known as brothels. It is interesting to note that despite the prevalence of such establishments in 1857, with a total of 410 in the Metropolitan District as demonstrated in a similar table, by ’68 there are only 2 as known to the police in Greater London, perhaps marking The Harlot’s House less as a work of true representation and historical accuracy and more as one containing a fair amount of embellishment. With a general consensus that the act of prostitution ”consists in the base perversion of a woman’s charms — the surrendering of her virtue to criminal indulgence” (Mayhew, 4) it is hardly surprising that prostitution became known in Victorian England as ”The Great Social Evil”. More surprising is Wilde’s apparent conformity to this notion.

As a pioneer in the aesthetic/decadent movement Wilde was supposedly advocating ”art for art’s sake”: the belief that Art should be freed from the constraints of morals and meaning and be something in and of itself, and it was in this vein he departed from the traditionally uptight, heavily moralistic Victorian style in his works such as “The Decay of Lying.” However, in The Harlot’s House he dehumanises prostitutes to a cruel extent:

Like strange mechanical grotesques,

Making fantastic arabesques,

The shadows raced across the blind.

We watched the ghostly dancers spin

To sound of horn and violin,

Like black leaves wheeling in the wind.

Like wire-pulled automatons,

Slim silhouetted skeletons

Went sidling through the slow quadrille

Wilde refers to them variously as ”mechanical grotesques”, ”automatons”, ”skeletons”, ”puppet[s]”, ”marionette[s]” and ultimately ”the dead”. He could hardly find more synonyms for ”manipulated, lifeless dolls”. One may be inclined to argue that he is not expressing personal opinion, and is, by definition, creating ”Art for Art’s sake”, yet this utter disrespect for and lifeless depiction of prostitutes is also evident, if to a lesser degree, in his poem, “Impression Du Matin” (Hawes):

But one pale woman all alone,

The daylight kissing her wan hair,

Loitered beneath the gas lamps' flare,

With lips of flame and heart of stone.

Prostitution was not alone as a violation of Victorian morality. ”The pervert, child masturbator, homosexual, hysteric, prostitute, primitive and nymphomaniac, all emerged as distinctly classified sexual species possessing their own internal "secret" which had been revealed by the penetrating gaze of science” (Ridgway). Homosexuality in particular was considered a heinous crime, punishable by death right up until 1861. Thus Wilde’s apparent disgust for prostitutes is stranger still: not only was he known to have committed acts of homosexuality, (indeed later, in 1895, he was sentenced to two years’ hard labour because of them,) and thus one could suppose he might share a certain camaraderie with prostitutes as fellow outlaws of Victorian propriety, but those acts were allegedly with male prostitutes!

Perhaps his abhorrence of the prostitute is actually a form of self-criticism, perhaps he really did consider them the scum of the earth, or perhaps The Harlot’s House is truly ”Art for Art’s sake”. In any case, personal connections aside, Wilde’s depiction of whores is very in keeping with the view of prostitutes as held by the vast majority of Victorian society, as demonstrated by the dubbing of it as ”The Great Social Evil”. The fact that by the time he wrote it there were very few brothels officially in existence serves to emphasise the narrow-mindedness of society and their limited perception of prostitution.

Appendix

As pertaining to this table Acton states:

It is, in the first place, desirable that the reader should understand the distinction between the three classes of houses, termed by the police, brothels. The first, or ”houses in which prostitutes are kept,” are those whose proprietors overtly devote their establishments to the lodging, and sometimes to the boarding, of prostitutes only . . .

By ”houses in which prostitutes lodge,” the reader must understand those in which one or two prostitutes occupy private apartments, generally with, though perhaps in rare cases without, the connivance of the proprietor . . .

”Houses to which prostitutes resort” represent night houses — the brothels devoted to casual entertainment of these women and their companions, and the coffe-shops and supper-shops which they haunt . . .

The ”well-dressed, living in lodgings” prostitute is supposed to be the female who . . . eschews absolute ”street-walking” . . .

The ”well-dressed, walking the streets” is the prostitute errant, or absolute street-walker, who plies in the open thoroughfare and there only . . .

The ”low prostitute, infesting low neighbourhoods,” is a phrase which speaks for itself (p. 7).

Later, on the differentiation between the ”classes” of prostitutes Acton notes:

The order may be divided into three classes — the ”kept woman” (a repulsive term, for which I have in vain sought an English substitute). Who has in truth, or pretends to have, but one paramour, with whom she, in some cases, resides, the common prostitute, who is at the service, with slight reservation, of the first comer, and attempts no other means of life’ and the woman whose prostitution is a subsidiary calling (p. 28).

Related Material

Works Cited

Acton, William. Prostitution, Considered in Its Moral, Social, and Sanitary Aspects in London and Other Large Cities and Garrison Towns, with Proposals for the Control and Prevention of Its Attendant Evils. London: John Churchill and Sons, 1870. Print.

Allingham, Philip V. "Oscar Fingal O'Flaherty Wilde (1854-1900)." The Victorian Web. Web. 17 May 2010.

E.M Sigworth and T.J Wyke. “ Study of Victorian Prostitution and Venereal Disease.” in M. Vicnius, Suffer and be still. Women in the Victorian Age. London: Methuen, 1980. Print.

Hawes, Kenna. "The Pervasion of Prostitutes." The Victorian Web. Web. 17 May 2010.

Landow, George P. "Early and Mid-Victorian Attitudes towards Prostitution." The Victorian Web. Web. 17 May 2010.

Mayhew, Henry, and William Tuckniss. London Labour and the London Poor: a Cyclop�dia of the Condition and Earnings of Those That Will Work, Those That Cannot Work, and Those That Will Not Work. London: Griffin, Bohn, and Company, 1861. Print.

Ridgway, Stephan. "Sexuality & Modernity: Victorian Sexuality." Isis Creations: Weaving Webs With Peoples. <>. Web. 17 May 2010.

Walkowitz, Judith R. Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class, and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1980. Print.

Wikipedia. "Contagious Diseases Acts." Wikipedia. Web. 17 May 2010.

Last modified 18 May 2010