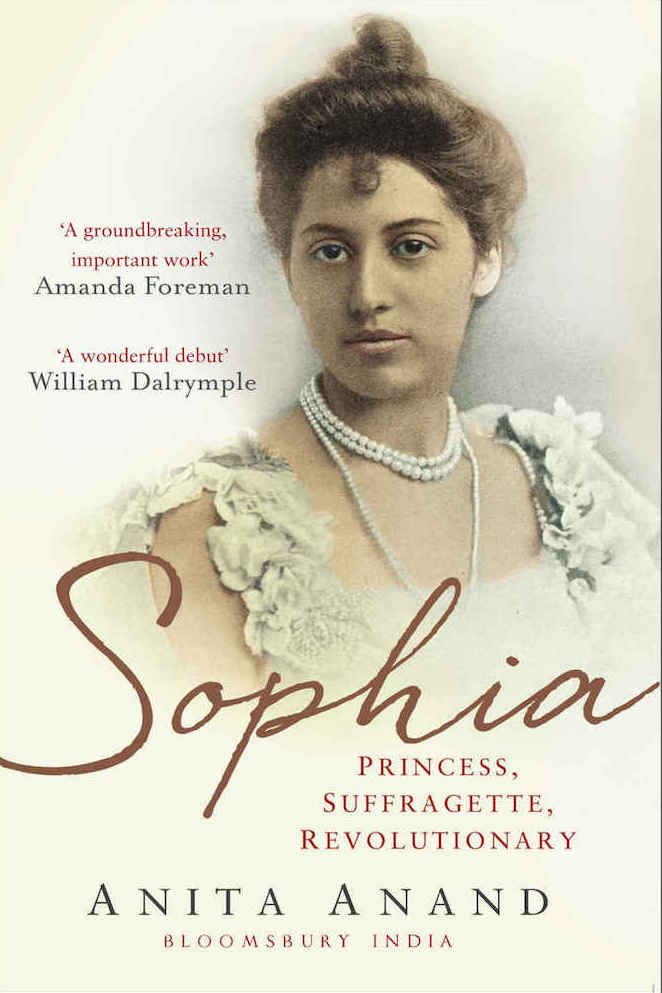

The book is well illustrated, but the photographs here (apart from the first, of the book cover), are from our own website, or were sourced or taken by the present author. You may use the latter without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information where available.]

Sophia Duleep Singh was born in 1874 to Maharajah Duleep Singh and his first wife, Bamba (née Muller). Before Anita Anand brought Sophia's remarkable life to our attention, her father's story had been much more familiar than hers, mainly perhaps because of his connection with the Koh-i-Noor diamond. The earliest part of Duleep's story is certainly arresting, not to mention troubling to British readers already burdened with the guilt of Empire. Heir to the riches of the Sikh kingdom in the Indian subcontinent (including the iconic diamond), the young Maharajah had survived the kingdom's overthrow by the British and the machinations that removed the older heirs to it. But he had been promptly separated from his ambitious mother, and consigned for the rest of his formative years to the guardianship of a Scottish surgeon and his wife, the Logins, in the distant cantonment town of Fategarh. Still only eleven years old, he had been prevailed upon to sign away his rights both to kingdom and fortune — including the diamond. He had also converted to Christianity. At the age of fifteen he had come to England at his own request, quickly establishing himself as a favourite of Queen Victoria.

Franz Winterhalter's portrait of Duleep Singh as a young man (in 1854).

The sad story of Duleep's later life, including his reconversion to his ancestral faith and frustrated dream of returning to India to reclaim his lost rights, is also well known, at least in outline. But much less has been said about his wives and children. By his first wife, Bamba, who was of mixed German and Abbysian blood, Duleep had four sons and three daughters: one died in infancy; the others were, in birth order, Victor, Frederick, Bamba, Catherine, Sophia and Edward. By his second wife, previously a St James's hotel chambermaid called Ada Weatherill, he had another two children, Pauline and Irene (the latter's second name, by which she was known). Of these eight, then, Sophia was the youngest daughter by his first wife. She would grow up to be in some ways very much a part of her times, but in others a little outside them — something, in fact, of a revolutionary, as Anand's subtitle claims. Her exploits take us well into the twentieth century, but also have much to tell us about the end of the nineteenth.

Despite being a godchild of the Queen, Sophia experienced a great deal in her early life that might have broken a lesser person — a whole string of misfortunes, in fact. These included her father's desertion as he took up with other women; her mother's consequent depression, from which she sought relief in alcohol; the loss of the palatial family home, Elveden Hall in Suffolk, as a result of Duleep's neglect and lifestyle; her mother's death in 1887 which enabled her father to regularise his relationship with Ada; and last but not least, her favourite brother Edward's death in 1893, when he was only thirteen. Yet, unexpectedly, the shy and awkward young Sophia blossomed into strong, determined woman, who partook of the new freedoms becoming available to her sex, and championed both the Indian struggle for independence and, more actively and prominently, the suffragette cause in England.

An early sign of her emergence from the shadows, not long after she and her sisters "came out" in Buckingham Palace in 1894, was her participation in the new sport of cycling:

Soon Sophia became a poster girl for a growing and evangelical cycling movement. She was photographed with her Columbia 41 in Richmond Park, and in Battersea, where the most fashionable "wheel people" tended to congregate. Publications such as The Sketch featured photographs of her posing stiffly but proudly with her bicycle, declaring that she was very fond of the outdoor life "and simple amusements which are felt to be the birth right of every happy, healthy girl, be she Princess or peasant." The article went on to describe Sophia as a "first-rate cyclist." [132; quoting the high society Sketch of 1896]

Another sign of her emancipation was that she began smoking, receipts from the estate revealing that she ordered quantities of expensive and exotic cigarettes from Cairo. She was a keen horsewoman, and took a great interest in dog breeding, entering her magnificent Borzois at dog shows. She also indulged her competitive streak in hockey matches: "The world's first women's field hockey clubs were emerging at the turn of the century, and Sophia was a keen and talented sportswoman." All in all, continues Anand, "[t]he timid girl who used to squirm before the camera was now an unabashed show-off" (134). Her activities at this point give us precious insights into the life of the racier kind of well-to-do young English woman in the late Victorian period.

However, the world was opening up for her now, and there were soon nobler causes into which she could channel her energies. In 1894, after finishing her schooldays in Brighton, she had stayed in Germany and made a Grand Tour around the Mediterranean with her sisters Catherine (by now a graduate of Oxford in French and German) and Bamba (who had failed to get a degree). On her return, she was granted a grace-and-favour residence at Faraday House, close to Hampton Court Palace, where she enjoyed living. But again in 1900 she ventured forth, going East with Bamba, who felt the pull of India more than she did, and hoped to get as close to it as she could — despite the government's fears that Duleep's offspring would become a focus of rebellion there. In the event, they disembarked briefly in Colombo before travelling from Japan to America, where Bamba stayed on to pursue her dream (never fulfilled) of becoming a physician. Later, though, Sophia and both her sisters visited the subcontinent itself. They went out, uninvited, for the Delhi Durbar of 1903, in honour of Edward VII's accession. Not unexpectedly, this first visit to her father's country made a huge impact on Sophia, particularly because the sisters were shunned by the British but welcomed enthusiastically by the Sikhs. While Bamba would settle in India and become deeply involved in the struggle for independence, after nine months Sophia decided to return to Hampton Court. But the experience of seeing the poor and downtrodden there was the prelude to her commitment to more important causes at home than winning dog shows or hockey matches.

Sophia selling copies of the Suffragette outside Hampton Court, courtesy of the British Library (there marked public domain).

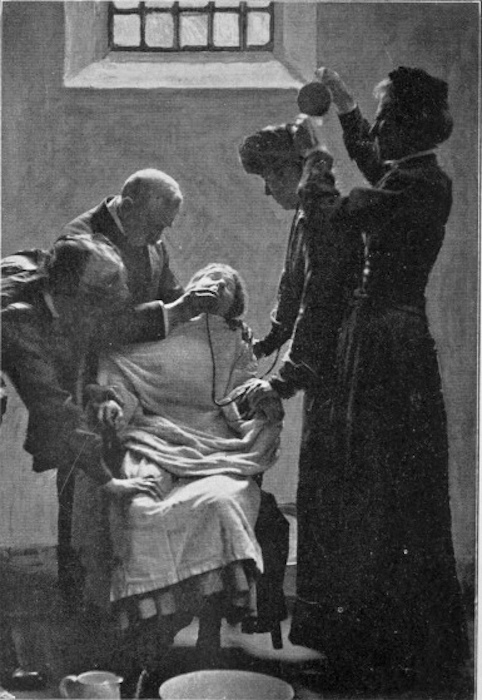

Sophia's new and more serious frame of mind was evident from the moment her ship docked, and the cold, "thin, dark and hungry" lascars of the East India Company caught her eye (161). Helping them was to be the first of her good causes. But what drew her most was the battle for women's voting rights — the suffragette movement. Anand's book is full of interest throughout, but the extent and nature of Sophia's contribution here is the most surprising aspect of it: once converted to this cause, she proved invaluable, not least because of her celebrity status as an Indian Princess. This was as effective in attracting publicity in England as it had been in India. She raised funds, attended meetings, and distributed propaganda. Nor did she dissociate herself from the increasing militancy of the movement. In 1909 she signed up as a tax resister ("No taxation without representation," 241), and assiduously courted arrest, speaking out in court against the injustice of being asked to contribute to the state without having any say in the way her money would be used. Evidently fearing the fall-out, officialdom would not allow her to be sent to prison, but Anand includes some graphic descriptions of her co-activists' horrendous experiences in jail. Force-feeding was a much worse kind of torture than most readers may have realised.

"Forcible feeding with the nasal tube." Source: Pankhurst, facing 433.

There is no mention of Sophia in Sylvia Pankhurst's record of this period, and even those previously aware of Sophia's rather exotic presence in the movement may not have realised just how prominently she figured in it. On 18 November 1910, for instance, Sophia was in the forefront of the demonstration in favour of the vetoed Conciliation Bill, which was intended to grant at least some classes of women the right to vote. Following just behind Emmeline Pankhurst and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, she was by far the youngest of the leading suffragettes, and fought back with a vengeance against police brutality in the notorious skirmishes which ensued. Confirmation that she had won admiration and affection for her efforts in the cause came when her supporters bought back for her the jewellery seized from Faraday House in lieu of taxes. Not surprisingly, then, she was among the select few who saw Pankhurst off on her consciousness-raising tour of America in October 1911. "Sophia's place at the heart of the movement was confirmed, as was its place in her own heart" (175).

Sophia would continue to support the suffragette cause publicly and prominently. Her wish for Indian independence, strengthened by a six-month stay with Bamba in India in 1906-7, could not but take second place to this more immediate cause. But her loyalties to her father's country were apparent when she volunteered to help nurse the wounded Indian soldiers brought to the Brighton Pavilion during and after World War I. Although or perhaps because Sophia never married, her personal life would involve her in other caring roles, including a close relationship with a goddaughter (her housekeeper's little girl), and taking in evacuees in August 1940. The bungalow gifted to her by her sister Catherine in Penn, Buckinghamshire, became a haven for them as well as for herself, providing her with the family she had missed out on during her colourful life.

This splendid equestrian statue of Duleep Singh on Butten Island in Thetford, Norfolk,* by Denise Dutton, was unveiled by Prince Charles on 29 June 1999. Duleep Singh is shown wearing full ceremonial dress, and the inscription acknowledges that he was "compelled to resign his sovereign rights and exiled," and that the Sikh nation still "aspires to regain its sovereignty." — photographs by JB

Anand carries us along with her right through this life, and the lives of her siblings, up to her death in 1948. The narrative successfully combines pace with drama, and evokes sympathy for Sophia herself while bringing vividly to life the larger projects in which she played a part. Much that Sophia had longed for came to pass during her own lifetime. But there was sorrow too, about Emmeline Pankhurst's unexpected and now generally unremarked turn towards Imperialism, for instance, and of course about Partition. When the Sikh kingdom of the Punjab was divided between India and Pakistan, "[g]reat cities she had known and loved were split between irreconcilable new neighbours. Lahore went to Pakistan, Amritsar went to India and a river of blood ran between them, as Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs turned on one another with murderous ferocity. Sophia lived to see the British leave, and mourned what had been left in their wake" (370). At the root of the whole story of Duleep Singh and his progeny is the original injustice done to them in the name of Empire, and Anand, quite rightly, does not allow us to forget this.

*The statue is sited here because Sophia's brother Frederick lived nearby, in Blo' Norton Hall. A generous local benefactor, much loved by many, Freddie kept an open door for all his family, and Sophia often stayed there. House and statue are both part of the impressive Anglo-Sikh Heritage Trail.

Related Material

- [Review of] William Dalrymple and Anita Anand's Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Famous Diamond

- The Battle for Women's Suffrage — A Timeline

- H.H. Sophie Duleep-Singh (as a "Doggy Person")

- Maharajah Duleep Singh, the last ruler of the Sikh kingdom of Punjab

- Portrait of Maharajah Duleep Singh

- [Offsite] The Anglo-Sikh Heritage Trail

Bibliography

Book under review: Anand, Anita. Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary. Bloomsbury, 2015. London: Bloomsbury, 2015. £20.00. 416 + xiii pp. ISBN 978-1-4088-3545-6.

Pankhurst, Sylvia. The suffragette; the history of the women's militant suffrage movement, 1905-1910. New York: Sturgis and Walton, 1911. Internet Archive. Contributed by Cornell University Library. Web. 20 September 2018.

Created 6 November 2020

Last modified 29 July 2024