The following passage comes from the author's The Destruction of Lord Raglan, (Longmans, 1961), pp. 112-13, used here with the author's kind permission. Copyright, of course, remains with Dr. Hibbert. Alvin Wee of the University Scholar's Programme, created the electronic text using OmniPage Pro OCR software, and created the HTML version. — Marjie Bloy Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, National University of Singapore.

The order had been written to send the cavalry to the Causeway Heights where the Russians were taking away the British guns. The cavalry was in the valley and could not see the events to which Lord Raglan referred. The result was the Charge of the Light Brigade on 25 October 1854. This narrative begins after Raglan has sent the order to Lord Lucan.

General Airey's A.D.C., Captain Lewis Edward Nolan, was a remarkable young man. His Irish father was in the British Consular service, his mother was Italian. He was extremely intelligent, goodlooking and excitable. He had written books on cavalry tactics and was considered by his fellow-officers as something of a prig. 'He writes books,' Lord George Paget said with some distaste, 'and was a great man in his own estimation and had already been talking very loud against the cavalry.' His contempt for both Lucan and Cardigan, but particularly Lucan, was violently and frequently expressed. He was, however, a superbly skilful horseman and it was because of this that Lord Raglan had chosen him rather than a more respectful officer to take the order to Lord Lucan six hundred feet below. A.D.C.s with previous orders had taken their horses carefully down, picking their way cautiously. Nolan went diving down the hill by the straightest and quickest route.

He galloped up to Lord Lucan and handed him the order. Lucan read it slowly with that infuriating care which drove more patient men than Nolan to scarcely controllable irritation. He read it, in fact, as he himself later confessed, 'with much consideration — perhaps consternation would be the better word — at once seeing its impracticability for any useful purpose whatever'. He urged 'the uselessness of such an attack and the danger attending it'.

'Lord Raglan's orders are,' Captain Nolan said, already mad with anger, 'that the cavalry should attack immediately.'

'Attack, sir! Attack what? What guns, sir? Where and what to do?'

'There, my Lord!' Nolan flung out his arm in a gesture more of rage than of indication. 'There is your enemy! There are your guns!' And leaving Lord Lucan as muddled as before, he trotted away to ask Captain Morris if he might charge with the 17th Lancers.

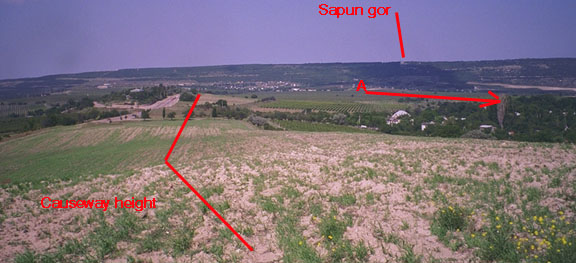

Standing in the center of the Causeway height looking down its length toward Sapun Gor ridge. The Light Brigade charged down the north valley and passed through the Russian artillery line. I am grateful to John Sloan for permission to use the photograph. Click on the thumbnail for a larger image.

The trouble was that Lord Lucan had no idea what he was intended to do. He could not, on the plain, see nearly as far as Lord Raglan could on the hills above him. He could not see any redoubts. And he could not see any guns being carried away. Since the battle had begun he had taken no steps to find out what was happening beyond the mounds and hillocks and ridges which cut off his view of the ground that had fallen into the hands of the enemy. The only guns in sight were at the far end of the North Valley, where a mass of Russian cavalry was also stationed. Those must presumably be the ones Lord Raglan meant. Certainly Nolan's impertinent and flamboyant gesture had seemed to point at them. His mind now made up, Lord Lucan trotted over to Cardigan and passed on the Commander-in-Chief's order. Coldly polite, Lord Cardigan dropped his sword in salute.

Certainly, Sir,' he said in his loud but husky voice. 'But allow me to point

out to you that the Russians have a battery in the valley in our front, and

batteries and riflemen on each flank.'

I know it," replied Lucan. 'But Lord Raglan will have it. We have no choice

but to obey.'

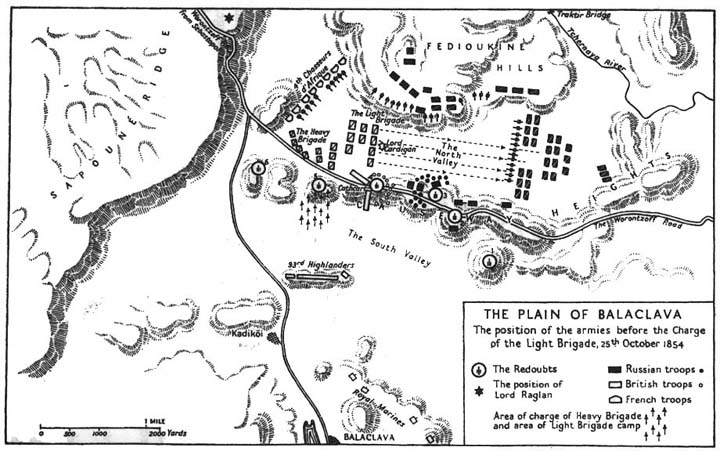

Map of the "Valley of Death": the plain at Balaclava just before the Charge of the Light Brigade. Click on the thumbnail for a larger image.

Cardigan saluted again, turned his horse, murmuring loudly to himself as he did so, 'Well, here goes the last of the Brudenells!', and he rode up to Lord George Paget. On the way he passed some men of the 8th Hussars who were smoking pipes. Their colonel angrily told them to put them out as they were 'disgracing his regiment by smoking in the presence of the enemy'. Paget himself was smoking a 'remarkably good' cigar and was embarrassed by Colonel Shewell's comment and then annoyed with Cardigan, who, after telling him to take command of the second line, added, 'and I expect your best support — mind, your best support', repeating the last sentence 'more than once'.

'Of course, my Lord. You shall have my best support,' Paget replied, obviously nettled. He decided to keep his cigar.

Cardigan galloped back to the front of the brigade and drew it up in two lines. The 13th Light Dragoons were placed on the right of the front line, the 17th Lancers in the centre, the 11th Hussars on the left but slightly behind the regiments to the right of them. The 4th Light Dragoons and the 8th Hussars formed the second line. At the last moment Lucan, without consulting Cardigan, told Colonel Douglas to withdraw the 11th Hussars, Cardigan's regiment, from the first line and to take up a position in support of it.

Cardigan himself rode forward to sit for a moment quite still and bolt upright in his saddle well in front not only of the first line but also of his staff. The spectators on the hills above excitedly leaned forward to watch what Camille Rousset afterwards referred to with cruel aptness as 'ce terrible et sanglant steeple-chase". They could see quite clearly the two white legs of Cardigan's chestnut charger.

The Charge of the Light Brigade by R. Caton Woodville. This picture graciously has been shared with the Victorian Web by from Stephen Luscombe, from his website, The British Empire, and to whom thanks are due. Copyright, of course, remains with him.

Click on the image for a larger view.

They had, indeed, a magnificent view. They were on the Sapouné Ridge, which at this point overlooks the valley from its eastern end and falls down to the plain in a succession of grass-covered steps. On these steps those with no duties to perform sat in comfort and safety to watch the battle. Below them stretched the long and narrow North Valley; on their right the Causeway Heights; on their left the Fedioukine Hills. In front of them at the end of the valley, and facing the Light Brigade immediately below them, were the squadrons of Russian cavalry which had retreated over the Causeway Heights from the Heavy Brigade. Twelve guns had been unlimbered in front of them; three fresh squadrons of Lancers stood on each of their flanks; along the Fedioukine Heights were four additional squadrons of cavalry, eight battalions of infantry and fourteen guns. Opposite them, across the valley on the Causeway Heights, were the eleven battalions that had stormed upon the Turks and were now being gently prodded by Cathcart, and with them were a further thirty-two guns. Only a madman, as Lucan afterwards said, would expect men to charge into that open, mile-long jaw.

The Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava. I am grateful to John Sloan for permission to use this image from the Xenophongi web site and which graciously he has agreed to share with the Victorian Web. Copyright, of course, remains with him. Click on the image to enlarge it.

'The Brigade will advance,' Lord Cardigan said in a strangely quiet voice.

Lord Raglan and his staff did not immediately realise that anything had gone wrong. The direction of the advance was perhaps a little inclined to the left but not yet alarmingly so, and soon no doubt when the pace quickened the Light Brigade would swing to the right on to the Causeway Heights. This undoubtedly was what the Russians were expecting, for as the cavalry came slowly but determinedly towards them they withdrew from all but one of the captured redoubts and formed up in squares near the crest of the ridge. Here was Sir George Cathcart's opportunity, and some of his staff anxiously waited for him to take quick advantage of it. His division was still halted in the position it had taken up an hour or so previously, but he refused to move it, even though the redoubts he had been ordered to recapture were now no longer occupied. A staff officer urged him to advance. He said no, his mind was quite made up on the matter, and he would write to Lord Raglan.

For the first fifty yards the Light Brigade advanced at a steady trot. The guns were silent. Lord Cardigan in his splendid blue and cherry-coloured uniform with its pelisse of gold-trimmed fur swinging gently on his stiffly thin shoulders looked, as Lord Raglan afterwards said of him, as brave and proud as a lion. He never glanced over his shoulder, but kept his eyes on the guns in his front.

Suddenly the beautiful precision and symmetry of the advancing line was broken. Inexcusably galloping in front of the commander came that 'impertinent devil' Nolan. He was waving his sword above his head and shouting for all he was worth. He turned round in his saddle and seemed to be trying to warn the infuriated Lord Cardigan and the first line of his men that they were going the wrong way. But no one heard what words he was shouting, for now the Russians had opened fire and his voice was drowned by the boom and crash of their guns. A splinter from one of the first shells fired flew into Nolan's heart. The hand that had been so frantically waving his sword remained rigidly above his head, and his knees, as if even in death they could not forget the habits of a lifetime, still gripped the flanks of his horse. The horse turned round and, as his rider's sword slipped from the still raised hand, he galloped furiously back with his terrifying burden, which suddenly gave forth a cry so inhuman and piercingly grotesque that one who heard it described it as 'the shriek of a corpse'.

The pace began to quicken, and there could be no doubt now that most of these seven hundred horsemen were riding to their death. From three sides the round shot flew into the ranks and the shells burst between them, opening gaps which closed with so calm and unhurried a determination that men and women watched from the safety of the hills with tears streaming down their cheeks, and General Bosquet murmured, unconsciously delivering himself of a protest against such courage which was to be remembered for ever, 'C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre.' 'The tears ran down my cheeks,' General Buller's A.D.C. wrote, 'and the din of musketry pouring in their murderous fire on the brave gallant fellows rang in my ears.' 'Pauvre garçon!' said an old French general standing at his side, trying to comfort him, patting him on the shoulder. 'je suis vieux, j'ai vu des batailles, mais ceci est trop.'

Cardigan was still in front. An excited officer of the 17th Lancers rode up alongside him, and Cardigan held out his sword across his breast. 'Steady! Steady! the 17th Lancers,' Cardigan shouted above the roar of the guns.

Behind him could be heard the fragmented shouts of squadron commanders — 'Close to your centre! "Do look to your dressing on the left!' 'Keep back, Johnson, back!' But more frequently than any other order — 'Close in! Close in! Close in to the centre!' For men and horses were falling now in appalling numbers, and with every fifty yards the charging lines became narrower, more ragged, split and uneven, more confused. Wounded men stumbled back through the muddle of bleeding horses and their dead and dying friends. Terrified riderless horses thundered out of the smoke.

Seeing the Light Cavalry massacred in front of him, Lord Lucan turned to Lord William Paulet and said to him, 'They have sacrificed the Light Brigade, they shall not have the Heavy, if I can help it.' And he ordered the halt to be sounded, withdrawing the brigade to a position where he might be able to prevent the light cavalry being pursued on its return. Wounded in his leg, he had shown complete indifference under fire and earned the grudging admission of one of his most violent critics that 'Yes, he is brave, damn him.' It took courage of another sort to withdraw the Heavy Brigade at such a time and give his enemies further opportunity to misunderstand his reason for doing so.

The Light Brigade was almost on the guns now. The officers had lost control of their men, who rushed on furiously, forcing Cardigan to increase his pace. Still so angry with Nolan that the only other thing he could think of was what it would be like to be cut in half by a cannon-ball, he picked out the smoke-filled space between the red flashes of two guns and rode straight for it. He was less than a hundred yards from the guns when all twelve of them simultaneously exploded in his face, rocking the earth and filling the air with thick smoke and flying metal. The Russian gunners had fired their last salvo before crawling under the guns. Cardigan was almost blown off his horse, but steadied himself and charged on into the battery at a speed, so he calculated with careful concern for accuracy, of seventeen miles an hour.

Only fifty men of the front line remained alive to follow him. But in they rushed, slashing at several brave Russian gunners who had not dived after their comrades under the guns but were pulling at the wheels in their efforts to drag them away. About eighty yards behind the guns were ranged the unmoving ranks of Russian cavalry. Cardigan looked at them with distaste. They all appeared to be gnashing their teeth. He took this to be a sign of greed at the sight of the rich fur and gold lace of his uniform. But other men had noticed before these 'numberless cages of teeth' in the pale, wide faces, and it was believed to signify not greed, nor even ferocity, but annoyance and impatience due to a thwarted wish to charge.

As Cardigan looked at them disdainfully, one of their officers, Prince Radzivill, looked back and remembered having met him at a party in London. He ordered some Cossacks to capture him alive. The Cossacks came forward, encircled him, and prodded him with their lances, cutting his leg. Cardigan glared scornfully at their wretched-looking nags, keeping his sword at the slope, as he considered it 'no part of a general's duty to fight the enemy among private soldiers', and then galloped away. He left his private soldiers to continue the fight while he trotted back up the valley to lodge a complaint about the infamous conduct of Captain Nolan.

Behind him the struggle continued unabated. Officers and men hacked at the Russian gunners, who hunched their heads between their shoulders as they tried to drag off their guns; while beyond the guns Captain Morris with what remained of the 17th Lancers charged at a mass of Russian cavalry and drove them back in disorder. He pursued them for some way until an enormous number of Cossacks forced his men back again.

Another body of Cossacks rode down on the men still fighting in the battery. Colonel Mayow, the Brigade Major, led the men out and drove the Russians off, as Lord George Paget galloped up and charged into the battery with the second line. The 4th Light Dragoons fell upon the gunners with a frightening savagery and massacred them with the ferocious excitement of Samurai. One British officer, maddened by the smell and sight of blood, clawed frenziedly at them with his bare hands, another swung his word in the air screaming hysterically.

When all the Russian gunners were dead, the Dragoons charged on towards the cavalry beyond. But as they galloped through the still thick smoke, they ran into the 11th Hussars retreating before a vastly superior force of Russian lancers.

'Halt, boys!' Lord George shouted. 'Halt front. If you don't halt front, my boys, we're done.'

And so the two regiments, numbering between them less than forty men, stood at bay to face the advancing enemy. Suddenly a man shouted, 'They are attacking us, my Lord, in our rear.' It was true. Their retreat was cut off.

Lord George turned to Major Low. 'We are in a desperate scrape. What the devil shall we do? Where is Lord Cardigan?

But Lord Cardigan had trotted away, and there was only one thing that could be done.

'You must go about,' he called to the men, 'and do the best you can.'

The men rode hard and straight up the valley at the Russian lancers formed up across their line of retreat as fast as their 'poor tired horses would carry' them. The Russian lancers backed away as if they were preparing to fall on the flank of the retreating horsemen when they galloped past. But they did not do so. Restrained perhaps by that curiously indecisive leadership which was becoming a feature of Russian cavalry tactics, the lancers allowed Lord George's men to graze past them, half-heartedly pushing at them with their lances. Or perhaps it was that they were moved to compassion by the sight of these tattered remains of the most splendid-looking cavalry in the world.

For the men of the Light Brigade presented a pitiable sight. Their gorgeous uniforms were torn and smeared with blood, their horses as damp and bedraggled as water-rats. And they were the fortunate ones. Others went past on foot, alone or in pairs or dragging loved horses limping and bleeding to death behind them.

The ground was 'strewn with the dead and dying'. Horses in every position of agony struggled to get up, then floundered back again on their mutilated riders.

Even now the guns still fired at them. But only from the Causeway Heights. On the Fedioukine Hills the Russian artillery had been driven from their positions by a spectacular charge of the 4th Chasseurs d'Afrique, who had shown what brave horsemen can do when well directed and skilfully led.

The leader of the Light Brigade was already home. He, at least, felt clear of blame for the unskilful manner in which the brigade had been directed. 'It is a mad-brained trick,' he said to a group of survivors. 'But it is no fault of mine.'

He rode up to Lord Raglan to offer the same excuse.

'What did you mean, sir?' Raglan asked him, more angry than his staff had ever seen him before, shaking his head from side to side, the stump of his arm jumping convulsively in its empty sleeve. 'What do you mean by attacking a battery in front, contrary to all the usages of warfare and the customs of the service?'

'My Lord,' Cardigan said, confident of his blamelessness, 'I hope you will not blame me, for I received the order to attack from my superior officer in front of the troops.'

It was, after all, a soldier's complete indemnification. Lord Cardigan rode back to his yacht with a clear conscience. And when his anger had cooled Lord Raglan had to admit that the brigade commander was not to blame. He had 'acted throughout', he wrote in a letter typical of many generous comments on Cardigan's part in the disaster, 'with the greatest steadiness and gallantry, as well as perseverance'.

With Lucan, Lord Raglan was not so forgiving. Soon after his conversation with Cardigan, who had naturally put the entire blame on his brother-in-law, Raglan said to Lucan sadly, 'You have lost the Light Brigade.'

Lucan vehemently denied it. He had, he said, merely carried out an order given to him both in writing and verbally by an A.D.C. from Headquarters. Lord Raglan, according to Lucan, now made a curious reply.

'Lord Lucan,' he said, 'You were a lieutenant-general and should, therefore, have exercised your discretion and, not approving the charge, should not have caused it to be made.'

****

Under flags of truce the dead and wounded were brought back from the now silent valley, while patrols trotted slowly across the space separating the two armies. Horses streaming with blood and unable to get to their feet bit at the short grass with froth-covered teeth. And every now and then men winced at the sharp, melancholy sound of the farriers' pistols. Nearly five hundred horses were lost.

Of the 673 men who had charged down the valley less than two hundred had returned. The Russians, as well as the allies, were deeply moved by such heroism. General Liprandi could not at first believe that the English cavalry had not all been drunk. 'You are noble fellows,' he told a group of prisoners, 'and I am sincerely sorry for you.'

The allies had need of sympathy. The engagement could not, whatever feats of courage had been displayed, be considered a victory. Balaclava admittedly had not been taken, but the Russian armies now straddled the Causeway Heights. And the road, which ran along the top of them and which might have saved the army from some of the horrors of the coming winter, was lost.

Last modified 16 May 2002