[Added by Marjie Bloy, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, National University of Singapore, from Timothy Gowing, Voice from the Ranks: a personal narrative of the Crimean Campaign (Nottingham: 1895).

The morning of the 20th found us once more on our legs. Marshal St. Arnaud rode along our line; we cheered him most heartily, and he seemed to appreciate it. In passing the 88th the Marshal of France called out in English:

'I hope you will fight well today!'

The fire-eating Connaught Rangers at once took up the challenge, and a voice loudly exclaimed, 'Shure, your honour, we will! Don't we always fight well?'

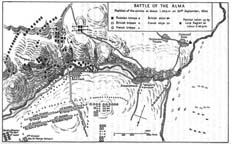

This map is taken from Christopher Hibbert's The Destruction of Lord Raglan, (Longmans, 1961), p. 94, with the author's kind permission. Copyright, of course, remains with Dr Hibbert. Click on the image for a larger view

Away we then went at a steady pace until about midday, the Light and Second Divisions leading, in columns of brigades. To describe my feelings in going into action, I could not. As soon as the enemy's round shot came hopping along, we simple did the polite — opened out and allowed them to pass on; there is nothing lost by politeness, even on a battlefield. As we kept advancing, we had to move our pins to get out of their way. Presently they began to pitch their shot and shell right amongst us, and our men began to fall. I know that I felt horribly sick — a cold shivering running through my veins — and I must acknowledge that I felt very uncomfortable; but I am happy to say that feeling passed off as soon as I began to get warm to it. It was very exciting work, and the sights were sickening.

We were now fairly under the enemy's fire — our poor fellows began to fall fast all around me. As we approached the village of Burliuk, which was on our side of the river (or what was called the right bank) the blackguards set fire to it; but still we pressed on, we by the right, the Second Division to the left.

We now advanced into the valley beneath, sometimes taking the ground to the right, then to the left. We had deployed into line, and presently we were ordered to lie down to avoid the hurricane of shot and shell that the enemy was pouring into us. A number of our fellows lay down to rise no more; the enemy had the range to a nicety.

We still kept advancing and then lying down again. Our men's feelings were now wrought up to such a state that it was not an easy matter to stop them. Up to the river we rushed and got ready for a swim, pulling off knapsacks and camp kettles. A number of our poor fellows were drowned, or shot down with grape and canister — which came amongst us like hail — while attempting to cross. Our men were falling now very fast. Into the river we dashed, nearly up to our arm-pits, with our ammunition and rifles on the top of our heads to keep them dry, scrambled out the best way we could — the banks were very steep and slippery — and commenced to ascend the hill.

From east to west the enemy's batteries were served with great rapidity, hence we were enveloped in smoke on what may be called the glacis and could not see much. We were only about 600 yards from the mouths of the guns; the thunder-bolts of war were, therefore, not far apart — and death loves a crowd. The havoc among the Fusiliers, both 7th and 23rd, was awful. Still, nothing but death could stop that renowned infantry. There were 14 guns of heavy calibre just in front of us, and others on our flanks — in all, some 42 guns were raining death and destruction upon us. A number of our fellows on reaching the top of the slippery bank were shot down and fell back dead, or were drowned in the Alma.

Up the hill we went, step by step, but with a fearful carnage. The fighting now became very exciting, our artillery playing over our heads, and we firing and advancing all the time. The smoke was now so great that we could hardly see what we were doing, and our fellows were falling all around; it was a dirty, rugged hill. When one gets into such a hot corner as this was, one has not much time to mind his neighbours. I could see that we were leading; the French were on our right and the 23rd Fusiliers on our left. We got mixed up with the 95th. Someone called out, 'Come on, young 95th — the old 7th are in front!'

The fighting was not of a desperate kind. My comrade said to me, 'We shall have to shift those fellows with the bayonet, old boy' — pointing to the Russians.

General Sir George Brown, Brigadier Codrington, our noble Colonel Yea, and in fact all our mounted officers, were encouraging us to move on. Sir G. Brown's horse was shot from under him just in front of us; but that fire-eating old warrior soon collected himself, jumped up waving his sword and shouting: 'Fusiliers, I am all right! Follow me, and I'll remember you for it!' Then led the way up that fatal hill on foot. The two Fusilier regiments seemed to vie with each other in performing deeds of valour. General Codrington waved his hat then rode straight at one of the embrasures and leaped his grey Arab into the breastwork. Others, breathless, were soon beside him.

With a ringing cheer we topped the Heights, and into the enemy's battery we jumped, spiked the guns, and bayoneted or shot down the gunners. Here we lost a great number of our men and, by overwhelming numbers, we (the 23rd, 33rd, 95th and Rifles) were mobbed out of the battery and a part of the way down the hill again.

The old 7th halted, fronted, and we lay down and blazed into their huge columns as hard as we could load and fire. In about twenty minutes, came up the Guards and Highlanders and a number of other regiments; His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge was with them, and he nobly faced the foe. They got a warm reception, but still pressed on up that fatal hill. Some will tell you that the Guards retired, or wanted to retire; but no — up they went manfully, step by step, both Guards and Highlanders, and a number of other regiments of the Second Division.

With another ringing cheer for Old England, at them we went again and re-topped the Heights, routing them from their batteries. Here I got a crack on the head with a piece of stone, which unmanned me for a time. When I came round I found the enemy had all bolted — the Heights of Alma were ours! The enemy were sent reeling from then in hot haste, with artillery and a few cavalry in pursuit. If we had only had three or four thousand cavalry with us, they would hot have got off quite so cheaply; as it was, they got a nasty mauling, such an one as they did not seem to appreciate.

After gaining the Heights — a victory that set the church bells of Old England ringing and gave schoolboys a holiday — we had time to count our loss. Alas, we had paid the penalty for leading the way! We had left more than half our number upon the field, dead or wounded, and one of our Colours was gone — but thank God, the enemy had not got it. It was found upon the field, cut into pieces and with a heap of dead and wounded all around it.

Kinglake, the author of The Crimean Campaign, says in the boldest language that 'Yea and his Fusiliers won the Alma'. As one of them, I can confirm that statement — we had to fight against tremendous odds. The brunt of the fighting fell upon the First Brigade of the Light Division, as their losses will testify. At one time the 7th Fusiliers confronted a whole Russian brigade and kept them at bay until assistance came up.

Our poor old Colonel exclaimed, at the top of the hill, when he sounded the assembly, 'A Colour gone! And where's my poor old Fusiliers? My God — my God!' And he cried like a child, wringing his hands.

After the enemy had been fairly routed, I obtained leave to go down the hill; I had lost my comrade and I was determined to find him if possible. I had no difficulty in tracing the way we had advanced, for the ground was covered with our poor fellows — in some places sixes and sevens, at others tens and twelves, and at other places whole ranks were lying. 'For these are deeds which shall not pass away, and names that must not, shall not, wither.'

The Russian wounded behaved in a most barbarous manner; they made signs for a drink and then shot the man who gave it them. My attention was drawn to one nasty case: a young officer of the 95th gave a wounded Russian a little brandy out of his flask and was turning to walk away when the fellow shot him mortally. I would have settled with him for his brutish conduct, but one of our men, who happened to be close to him, at once gave him his bayonet, and dispatched him. I went up to the young officer and, finding he was still alive, placed him in as comfortable a position as I could, and then left him, to look for my comrade.

I found him close to the river, dead. He had been shot in the mouth and left breast, and death must have been instantaneous. He was not in the presence of his glorified Captain; he was as brave as a lion, but a faithful disciple. He could not have gone a hundred yards from the spot where he told me we should 'have to shift those fellows with the bayonet.'

I sat down beside him and thought my heart would break as I recalled some of his sayings, particularly his talk to me at midnight of the 19th: this was about 6 p.m. on the 20th. I buried him with the assistance of two or three of our men; we laid him in his grave with nothing but an overcoat wrapped around him, and left him with a heavy heart.

In passing up the hill I had provided myself with all the water bottles I could, from the dead, in order to help to revive the wounded as much as possible. I visited the young officer whom I saw shot by the wounded Russian and found he was out of all pain. The sights all the way were sickening. The sailors were taking off the wounded as fast as possible, but many lay there all night, just as they had fallen.

The Russian officers were gentlemen, but their men were perfect fiends. The night after the battle, and the following morning, this was proved in a number of cases by their shooting down our men just after they had done all they could for them. Our comrades at once paid them for it either by shooting or bayoneting them on the spot. This was rough justice, but it was justice nevertheless; none of them lived to boast of what they had done.

I rejoined my regiment on the top of the hill, and was made Sergeant that night. Poor Captain Monk, of ours, was the talk of the whole regiment that evening. It appears that a Russian presented his rifle at him, close to his head. The Captain at once parried it and cut the man down. A Russian officer then tackled his in single combat, and he quietly knocked him down with his fist, with others right and left of him, until he had a heap all round him, and at last fell dead in the midst of them.

The 21st and 22nd were spent in collecting the wounded, both friend and foe. Ours were at once put on board ship and sent to Scutari; some hundreds of the enemy were collected in a vineyard on the slopes. The dead were buried in large pits — and a very mournful and ghastly sight it was, for many had been literally cut to pieces. It was a difficult matter really to find out what had killed some of them. Here, men were found in positions as if in the act of firing; there, as if they had fallen asleep; and all over the field the dead were lying in every position it was possible for men to assume. Some of those who had met death at the point of the bayonet presented a picture painful to look upon; others were actually smiling.

Such was the field of the Alma.

The first battle was now over, and as I wrote to my parents from the Heights — 'I hope that you will be able to make out this scrawl, as the only table I have is a dead Russian' — I thanked God I was still in the land of the living, and what's more with a whole skin — except an abrasion on the head caused by a stone — which a few hours ago had appeared impossible.

The three fusilier regiments that led the way suffered fearfully, the 7th Royal Fusiliers on the right, the 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers in the centre, and the 33rd on the left. Any one of these three regiments suffered more than the whole brigade of Guards or Highlanders combined — not that I wish to speak disparagingly of the gallant Guards or the noble Highlanders, I only wish to show on whom the brunt of the fighting fell.

Canrobert, a French Marshal, might well, in the excitement, exclaim, 'I should like to command an English division for a campaign, and it would be the d---- take the hindmost — I feel that I could then attain my highest ambition!'

A Russian wounded general, in giving up his sword as prisoner of war, stated that they were confident of holding their position for some days, no matter what force the allies could bring against them, adding that they came to fight men and not devils. Prince Menchikoff quitted the field in a hurry, for he left his carriage behind and all his state papers. He, poor man, had to eat a lot of humble pie, and we are told that he was furiously mad. He had been over-confident that he could hold us in check for three weeks and then put us all into the sea; he just held the heights for three hours after the attack commenced. Ladies even came out of Sevastopol to witness the destruction of the allies; but I fancy their flight must have been most distressing, while their feelings were not to be envied.

We remained on the Heights until the 23rd, and lost a number of men from cholera. The 57th joined us there, just too late for the battle; but the old 'die-hards' left their marks upon the enemy at Inkerman and throughout the siege of Sevastopol.

The morning of the 23rd found us early on our feet and en route for the fortress. We marched all day, our men fast dropping out from sickness. Our first halting-place was at Katcha, where we had a splendid view; our friends the Cossacks kept a little in front of us. On the 24th away we went again, nothing particular occurring, except that our unseen enemy — cholera — was still in the midst of us, picking off his victims. The Commander- in-Chief of the French, the gallant and gay Marshal St. Arnaud, succumbed to it. But we pressed on, the honour of three nations being at stake.

Nothing worthy of notice transpired until the 28th, when we thought we were going to have another Alma job. We began to get ready; artillery and cavalry were ordered to the front. The enemy got a slight taste of the Scots Greys, a few prisoners being captured. The Rifles got a few pop-shots at them, but it turned out afterwards that it was the rearguard of the enemy. A number of things were picked up by our people, but the affair ended in smoke; they evidently did not mean to try to oppose our advance — they had once attempted it and wanted no more of it — so the following day we marched on without interruption to the nice little village of Balaclava.

We had little or no trouble in taking it; the Russians, however, made a slight show of resistance, for the sake of honour. The Rifles advanced, we supporting them. A few shots were fired; but as soon as one or two of our ships entered the harbour and gave the old castle a few shots, they gave in, and our people at once took possession. The harbour was speedily filled with our shipping. Our men managed to pick up a few old hens and a pig or two, which came in very handy for a stew; and we got some splendid grapes and apples.

Next day we moved up to the front of Sevastopol, whither other divisions had gone on before us. The siege guns were soon brought up, manned by Marines and Jack Tars, and we quickly found out that we had a nice little job cut out for us.

We had plenty to do — at it from morning until night, and often from night again till morning — making trenches, constructing batteries, lying out all night as covering parties; and so it went on for some days. The enemy were no mean foe, and they pretty well peppered us — they would often fire shot after shot from their heavy guns at a single man. Soon they began to collect themselves from the thrashing at the Alma and we had some rough little tussles with them. We had as yet no tents, and consequently had to rough it, with only an overcoat, wet or dry — but we never were dry.

We must acknowledge that the enemy proved themselves worthy defenders of the fortress; they worked night and day to strengthen the lines of forts, huge batteries springing into existence like mushrooms, and stung us more than mosquitoes. It was evident to all that if the allies wanted Sevastopol they would find it a hard nut to crack, that it would be a rough picnic for us. Sir George Brown might well say that the longer we looked at it, the uglier it got.

Thus day after day rolled on. Our tents at last began to come up in driblets. Guns, shot, shell, and all kinds of warlike implements, were daily arriving. So things proceeded until the morning of the 17th of October, when the first shot was fired and the ball was opened, and from 6 until 9 a.m. they were at it; as fast as our men could load and fire it was ding-dong hard fighting. At 9 a.m. one of the French magazines went up with a crash. Still our people kept at it — it was, as far as we could see, all fair give and take. The White Tower was knocked all to pieces very quickly, but huge works were erected all around it, and called the Malakoff.

Our poor sailors suffered very heavily; but I must say some of it was their own fault, for they would persist in jumping on the top of the batteries to see the effect of the shots — they were shot down as soon as they got up, for the enemy's sharpshooters were ever on the alert. To hear some of their expressions at times would have made a pig laugh.

We had some rough work on the 17th and 18th; the French fire was now nearly stopped and all the enemy's efforts were concentrated upon us. The first bombardment was a perfect failure — the enemy had evidently mounted some heavy guns during the night, for there was some very hard pounding; but our bluejackets — those Trafalgar Lambs and Nile Chickens stuck to it manfully. These brave fellows seemed weather-proof and almost disease-proof, for whilst our men were fast dying with cholera, brought about by exposure, the bluejackets were all alive, had comparatively good health, and seemed to enjoy the sport of 'playing at sogers'; Captain Peel's men were nice 'Bellerophon Doves'.

As for the United Fleets, they could not get in close enough to do much damage. The enemy did not seem to care about coming to blows with the fleet and, to prevent our ships from entering, they sank a number of their largest craft across the mouth of the harbour, thereby stopping the navigation.

Our allies the French proved themselves bricks, although they, with us, suffered heavily. We found it no child's play dragging heavy siege guns up from Balaclava; it was a long pull, and a strong pull, up to our ankles in mud which stuck like glue. Often on arrival in camp we found but little to eat, hardly sufficient to keep body and soul together; then off again to help to get the guns and mortars into their respective batteries, exposed all the time to the enemy's fire, and they were noways sparing of shot and shell.

We would have strong bodies in front of us, as covering parties and working parties; often the pick and shovel would have to be thrown down and the rifle brought to the front. Sometimes we would dig and guard in turn — we could keep ourselves warm, digging and making trenches and batteries, although often up to our ankles in muddy water.

All our approaches had to be done at night, and the darker the better for us. As for the covering party, it was killing work lying down for hours in the cold mud, returning to camp at daylight, wearied out with cold, sleepy and hungry — many a poor fellow suffering with ague or fever — to find nothing but a cold, bleak mud tent, without fire, to rest their weary bones in; and often not even a piece of mouldy biscuit to eat — nothing served out yet. But often, as soon as we reached camp, the orderly would call out:

'Is Sergeant G. in?'

'Yes. What's up?'

'You are for fatigue at once.'

Off to Balaclava, perhaps to bring up supplies in the shape of salt beef, salt pork, biscuits, blankets, shot or shell. Return at night completely done-up; down you go in the mud for a few hours' rest — that is, if there was not an alarm.

And thus it continued, week in and week out, month in and month out. So much for honour and glory! The enemy were not idle; they were continually constructing new works, and peppering us from morning until night. Sometimes they would treat us to a few long-rangers, sending their shot right through our camp. And we found often that the besiegers were the attacked party, and not the attacking.

Our numbers began to get very scanty — cholera was daily finding its victims. It never left us from the time we were in Turkey. It was piteous to see poor fellows struck down in two or three hours and carried off to their last abode. Nearly all of us were suffering more or less from ague, fever, or colds, but it was no use complaining — the doctors had little or no medicine to give. Our poor fellows were dropping off fast with dysentery and diarrhoea; but all that could stuck to it manfully. We had several brushes with the foe, who always came off second best. The Poles deserted by wholesale from the enemy. Some of them would turn round at once and let drive at the Russians, then give up their arms to us, shouting 'Pole, Pole!'

We knew well that the enemy were almost daily receiving reinforcements; we had, as yet, received none. We were almost longing to go at the town, take it or die in the attempt to hoist our glorious old flag on its walls.

Last modified 16 April 2002