Added by Marjie Bloy, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, National University of Singapore, from Timothy Gowing, Voice from the Ranks: a personal narrative of the Crimean Campaign (Nottingham: 1895).

he nights began to get very cold, and we found the endless trench

work very trying, often having to stand up to our ankles (and sometimes knees)

in muddy water, with the enemy pounding at us all the time with heavy ordnance,

both direct and vertical, guns often dismounted and platforms sent flying in all

directions; our sailors generally paid the enemy out for it. The Russians often

fought with desperation, but moral strength in war is to physical as three to

one. Our men had handled the enemy very roughly more than once since the Alma,

and they were shy at coming to close quarters unless they could take us by surprise.

he nights began to get very cold, and we found the endless trench

work very trying, often having to stand up to our ankles (and sometimes knees)

in muddy water, with the enemy pounding at us all the time with heavy ordnance,

both direct and vertical, guns often dismounted and platforms sent flying in all

directions; our sailors generally paid the enemy out for it. The Russians often

fought with desperation, but moral strength in war is to physical as three to

one. Our men had handled the enemy very roughly more than once since the Alma,

and they were shy at coming to close quarters unless they could take us by surprise.

Thus things went on day after day until the morning of the 25th October, 1854, when we awoke to find the enemy were trying to cut off our communications at Balaclava, which brought on the battle.

I was not engaged, but had started from camp in charge of twenty-five men on fatigue to Balaclava, to bring up blankets for the sick and wounded. It was a cold, bleak morning as we left our tents. Our clothing was getting very thin, with as many patches as Joseph's coat. More than one smart Fusilier's back or shoulder was indebted to a piece of black blanket, with hay bound round his legs to cover his rags and keep the biting wind out a little; and boots were nearly worn out, with none to replace them. There was nothing about our outward appearance lady-killing; we were looking stern duty in the face. There was no murmuring, however — all went jogging along, cracking all kinds of jokes.

We could hear the firing at Balaclava, but thought it was the Turks and Russians playing at long bowls, which generally ended in smoke. We noticed, too, mounted orderlies and staff officers riding as if they were going in for the Derby.

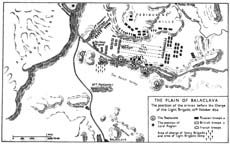

This map is taken from Christopher Hibbert's The Destruction of Lord Raglan, (Longmans, 1961), with the author's kind permission. Copyright, of course, remains with Dr Hibbert.

Click on the image for a larger view

As we reached the hills overlooking the plains of Balaclava, we could see our cavalry formed up, but none of us thought what a sight we were about to witness. The enemy's cavalry in massive columns were moving up the valley; the firing was at times heavy. Several volleys of musketry were heard. The Turks ran from our guns, but found time to plunder our camp. In a few minutes more the enemy got a slight taste of the 93rd Highlanders, and after satisfying themselves they were not all Turks who were defending our communications, they retired as quickly as possible. My party was unarmed, hence my keeping them out of harm's way.

One column of the enemy's cavalry advanced to within half a mile of our people, who were a handful compared with the host in front of them. It was soon evident our generals were not going to stop to count them, but go at them at once. It was a most thrilling and exciting moment.

The Charge of the Heavy Brigade at Balaklava from William Simpson's The Seat of War in the East, second series. I am grateful to John Sloan for permission to use this image from the Xenophongi web site, which graciously he has agreed to share with the Victorian Web. Copyright, of course, remains with him.

Click on the image for a larger view

As our trumpets sounded the advance, the Greys and Inniskillings moved forward at a sharp pace and as they began to ascend the hill they broke into a charge. The pace was terrific, and with ringing cheer and continued shouts they dashed right into the centre of the enemy's column. It was an awful crash as the glittering helmets of the boys of the Green Isle and the bearskins of the Greys dashed into the midst of levelled lances with sabres raised. The earth seemed to shake with a sound like thunder. Hundreds of the enemy went down in that terrible rush. It was heavy men mounted on heavy horses, and it told a fearful tale.

A number of the spectators, as our men dashed into that column, exclaimed, 'They are lost! They are lost!' It was lance against sword, and at times our men became entirely lost in the midst of a forest of lances. But they cut their way right through, as if they had been riding over a lot of donkeys. A shout of joy burst from us and the French, who were spectators, as our men came out of the column. It was an uphill fight of 500 Britons against 5,000 Muscovites.

Fresh columns of squadrons closed round this noble band with a view of crushing them — but help was now close at hand. With another terrible crash, and with a shout truly English, in went the Royal Dragoons on one flank of the column; and with thrilling shouts of 'Faugh-a-Ballagh' [1] the Royal Irish buried themselves in a forest of lances on the other. Then came thundering on the Green Horse (5th Dragoon Guards) and rode straight at the enemy's column.

The Russians must have had a bad time of it. At a distance, it was impossible to see the many hand-to-hand encounters; the thick overcoats of the enemy, we knew well, would ward off many a blow. Our men, we found afterwards, went in with point, or with the fifth, sixth, or seventh cuts about the head [2]. The consequence was, the field was covered pretty thickly with the enemy; but hundreds of their wounded were carried away. We found that they were all strongly buckled to their horses, so that it was only when the horse fell that the rider was likely to fall. But if ever a body of cavalry were handled roughly, that column of Muscovites were. They bolted — that is, all that could — like a flock of sheep with a dog at their tails. Their officers tried to bring them up, but it was no go; they had had enough and left the field to General Scarlett's band of heroes. How ever that gallant officer escaped was a miracle, for he led some thirty yards right into the jaws of death and came off without a scratch.

The victorious brigade triumphantly rejoined their comrades and were received with a wild burst of enthusiasm. It would be well if we could now draw the curtain and claim a glorious victory. The French officers were loud in their admiration of the daring feat of arms they had just witnessed; many of them said it was most glorious. Sir Colin Campbell might well get a little excited and express his admiration of the Scots Greys. This old hero rode up to the front of the Greys with hat in hand and exclaimed with pride:

'Greys, gallant Greys! I am past sixty-one years; if I were young again, I should be proud to be in your ranks. You are worthy of your forefathers!'

But they were not alone: it was the Union Brigade, as at Waterloo, that had just rode through and through the enemy and drew the words from Lord Raglan, who had witnessed both charges, 'Well done, Scarlett!'

The losses of this noble brigade were comparatively trifling, taking into consideration the heavy loss they inflicted upon the foe. The Union Brigade was composed of one English, one Irish, and one Scotch regiment; so it was old England, ould Ireland, and Scotland for ever!

But we now come to where someone had blundered. The light cavalry had stood and witnessed the heroic deeds of their comrades the heavies. Had we had an Uxbridge, a Cotton, or a Le Marchant, at the head of our cavalry, not many of the enemy's heavy column, which had just received such a mauling from the Heavy Brigade, would have rejoined their comrades. The light cavalry would have been let go at the right time and place, and the enemy would have paid a much heavier price for a peep at Balaclava.

The noble six hundred had not to wait much longer. They were all on the look-out for something. It comes at last. A most dashing soldier, Captain Nolan, rode at full speed from Lord Raglan with a written order to the commander of our cavalry, the late Lord Lucan:

Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance to the front, and try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Troop of horse artillery may accompany. French cavalry is on your left. Immediately. R. AIREY

Anyone without a military eye will be able to see at a glance that it was our guns (from which the Turks had run away) our commander wished to retake from the enemy; it could have been done without much loss, as General Sir G. Cathcart was close at hand with his division. This was not the first order sent to the commander of our cavalry. The former order ran thus:

Cavalry to advance and take advantage of any opportunity to recover the heights. They will be supported by the infantry, which have been ordered to advance on two fronts.

What heights? Why, the heights on which our spiked guns are! It must have been very amazing to our commander that his orders had not been obeyed, although some thirty-five precious minutes had elapsed. From the high ground he could see that the enemy were about to take our seven guns away in triumph, hence the order 'immediately'. The commander of our cavalry evidently lost his balance with the gallant Nolan, as we find from authentic works upon the war. Lord Lucan (who was irritable, to say the least of it) said to Nolan:

'Attack, sir? Attack what? What guns, sir?'

'Lord Raglan's orders,' he replied, 'are that the cavalry should attack immediately.'

Nolan , a hot-blooded son of the Green Isle, could not stand to be snapped at any longer, and he added, 'There, my Lord, is your enemy, and there are your guns!'

The order was misconstrued — and the noble six hundred were launched into the valley of death! Poor Captain Nolan was the first that fell. But they and he shall live renowned in story.

Thus far, I had been an eye-witness of one of the noblest feats of arms that ever was seen upon a battlefield. It spoke volumes to the rising generation. Go and do likewise. Never say die. A brave man can die but once, but a cowardly sneak all his life long. It told the enemy plainly the metal our cavalry were made of. They said that we were red devils at the Alma; it must be acknowledged that they got well lathered then, and now the Union Brigade of heavy horse had shaved them very roughly. As for the Light Brigade, with sickness, disease, a strong escort for our Commander-in-Chief, and mounted orderlies for the different generals, it hardly mustered the strength of one regiment on an Indian footing.

There was a lot of excitement on the hill-side when we found the Light Brigade was advancing, first at a steady trot, then they broke into a gallop. Their noble leader, the Earl of Cardigan, might well say, 'Here goes the last of the Cardigans! [3] Some one (an officer) said:

'What on earth are they going to do? Surely they are not going to charge the whole Russian army! It's madness!'

But, madness or not, they were simply obeying an order. And this noble band pressed on towards the enemy, sweeping down the valley at a terrific pace, in all the pride of manhood. Every man's heart on that hill-side beat high.

'They are lost! They are lost!' burst from more than one spectator.

The Charge of the Heavy Brigade at Balaklava from William Simpson's The Seat of War in the East, second series.

I am grateful to John Sloan for permission to use this image from the Xenophongi web site, which graciously he has agreed to share with the Victorian Web. Copyright, of course, remains with him. Click on the thumbnail for a larger image

The enemy's guns — right, left and front — opened on this devoted band. A heavy musketry fire was likewise opened; but still they pressed on. The field was soon strewn with the dead and wounded. It was a terrible sight to have to stand and witness without the power of helping them. The excitement was beyond my pen to express. Big briny tears gushed down more than one man's face that had resolutely stormed the Alma. To see their countrymen rushing at a fearful pace right into the jaws of death was a most exciting scene to stand and witness!

The field was now covered with the wreck of men and horses. They at last reached the smoke. Now and then we could hear the distant cheer and see their swords gleaming above the smoke, as they plunged into one of the terrible batteries that had swept their comrades down.

An officer very kindly lent me his field-glass for a short time. The field presented a ghastly sight, with the unnatural enemy hacking at the wounded — some trying to drag their mangled bodies from the awful cross-fire — but a few escaped the bloodthirsty Cossack's lance.

We could see the enemy formed up to cut off all retreat; but it was now do or die. In our fellows went with a ringing cheer, and cut a road through them; and now, to our horror, the brutish enemy opened their guns with grape upon friend and foe, thus involving all in one common ruin; and the guns again opened on their flanks.

It was almost miraculous how any of that noble band escaped. As each brigade or party came back they were greeted with a hearty cheer. Our gallant allies, the French, had witnessed the heroic deeds of the Light Brigade, and now the Chasseurs went at the enemy in a most dashing manner, to help to rescue the remains of such a noble band. The Chasseurs d'Afrique charged more like madmen than anything else; they had witnessed the Charge of the Light Brigade, and it had had the effect of rousing them to emulation. The chivalrous conduct of our allies on this field will always be remembered with gratitude; they had ten killed and twenty-eight wounded.

All cavalry charges are desperate work. As a rule, they are soon over; but they leave, particularly if successful, a heavily bloodstained mark behind. This was the only field on which our cavalry were engaged during the campaign; at the Alma a few squadrons were on the field, but not engaged. At Inkerman a portion of the cavalry were formed up — they then would have had a chance if the enemy had broken through the infantry. As far as the siege was concerned, they only did the looking-on part.

Our gallant allies admired much the conduct of our cavalry, both heavy and light. General Bosquet said that the charge of the Heavies was sublime; that of the Light Brigade was splendid 'but it was not war'.

We have not the slightest hesitation in asserting that the Light Brigade was sacrificed by a blunder. It is but little use trying to lay the blame on the shoulders of poor Captain Nolan; had he lived, the cavalry would have gone at our guns and recaptured them, or had a good try for it. It was Lord Lucan, and no one else, that ordered the charge. To say the least of it, it was a misconception of an order. But I am confident that Old England will long honour the memory of the noble six hundred.

Had the battle continued, the First and Fourth Divisions would have had a hand in the pie, as they were on the ground but not engaged.

Had my party been armed, I should most likely have gone down the hill at the double and formed up on the left of 'the thin red line' — the 93rd Highlanders. Shortly after the sanguinary charge of the Light Brigade, I moved forward as fast as I could. On arriving at Balaclava I found the stores closed up, and the Assistant Quartermaster-General ordered me to take my party on to the field to assist in removing the wounded, as far as it lay in my power.

Off I went at once. I found the cavalry still formed up. The Light Brigade were but a clump of men ... Noble fellows! They were few, but fearless still. I was not allowed to proceed further for some time, and I had the unspeakable pleasure of grasping more than one hand of that noble brigade. There was no mistaking their proud look as they gave me the right hand of fellowship!

A sergeant of the old Cherry Pickers, who knew me

well, gave me a warm shake of the hand, remarking, 'Ah, my old Fusilier, I told

you a week ago we would have something to talk about before long.'

'But, I replied, 'has there not been some mistake?'

'It cannot be helped now — we have tried to do our part. It will all come

out some day.'

My men carried a number of the Heavies from the field to the hospitals, then I got my store of priceless blankets and off we plodded through the mud back to camp; we had something to talk about on our way home.

Our gallant allies, the French, were in high glee — they could hardly control themselves. As soon as they caught sight of us, they commenced to shout, 'Bon Anglais, bon Anglais!' And so it continued until I reached our camp.

Exciting and startling events now rapidly succeeded each other: the victorious cavalry had hardly sheathed their swords after their conflict with the enemy when about 10,000, almost maddened with drink and religious enthusiasm, took another peep at our camp next day, supported by some thirty guns. This afterwards was called 'Little Inkerman', and was a stiff fight while it lasted.

About midday on the 26th October the enemy came out of the town in very strong columns and attacked us, just to the right of the Victoria Redoubt; the fighting was of a very severe nature. The Second Division, under Sir de Lacy Evans, received them first; and a part of the Light Division had a hand in it. The enemy made cock-sure of beating us and brought trenching tools with them, but were again doomed to be disappointed. We were hardly prepared for them but soon collected ourselves and closed upon them with the bayonet when, after some hard fighting, they were hurled from the field.

They paid dearly for a peep at our camp, leaving close upon 1,000 dead and wounded. They retired much quicker than they came, with our heavy guns sweeping them down by scores and cutting lanes through their columns. Our artillery on this occasion did great execution, whilst a continuous rain of Minié rifle balls mowed their ranks like grass, and for the finishing stroke they got that nasty 'piece of cold steel'; our huge Lancaster guns simply killed the enemy by wholesale.

General Bosquet kindly offered assistance, but the reply of our Commander was, 'Thank you, General, the enemy are already defeated and too happy to leave the field to me.'

The attack of the 26th was nothing more nor less than a reconnaissance in force, preparatory to the memorable Battle of Inkerman, but it cost them heavily, while we also lost a large number of men. On this field the brutal enemy distinguished themselves by bayoneting all our wounded that the pickets were compelled to leave behind in falling back for a short distance. The stand made by the pickets of the 30th, 55th, and 95th on our right was grand, for they retired disputing every stone and bush that lay in their way.

The following morning our commander, under a flag of truce, reminded the Russian chief that he was at war with Christian nations and requested him to take steps to respect the wounded, in accordance with humanity and the laws of civilized nations. Nevertheless, the remonstrance did not stop their brutality. A few days later, on the memorable field of Inkerman, the Russians murdered almost every wounded man who had the misfortune to fall into their hands.

Whilst the pickets were holding on with desperation, the Royal Fusiliers and portions of the Royal Welch, 33rd Duke's Own, and 2nd Battalion Rifle Brigade, went with all speed to the Five-Gun Battery to reinforce the pickets there, and a portion of us were directed to the slopes of the White House Ravine.

We had just got into position when we observed one of the enemy retiring towards Sevastopol with a tunic on the muzzle of his rifle, belonging to one of the Fusiliers who was on fatigue in the ravine, cutting wood, when the attack commenced. Having nothing to defend himself with, he had to show his heels.

One of the Rifle Brigade at once dashed off shouting that the tunic should not go into the town. As the Rifleman neared, the Russian turned and brought his rifle to the present. John Bull immediately did the same. As luck would have it, neither of them was capped [4] . They closed to box [fist-fight]; the Briton proving the Russian's superior at this game, knocked him down, jumping on top of his antagonist. But the Russian proved the strongest in this position and soon had the Rifleman under. We watched them but dared not fire. A corporal of the Rifles ran as fast as he could to assist his comrade, but the Russian drew a short sword and plunged at our man, and had his hand raised for a second. The corporal at once dropped on his knee and shot the Russian dead.

Our men cheered them heartily from the heights. They were both made prisoners of war by an officer, and in due course brought before the commander of our forces, who made all enquiries into the case and marked his displeasure with the young officer by presenting £5 to the gallant Rifleman for his courage in not allowing the red coat to be carried into Sevastopol as a trophy, and promoted the corporal to sergeant for his presence of mind in saving the life of his comrade. No end of dare-devil acts like the above could be quoted, for the enemy always got good interest for anything which they attempted.

Our numbers were now fast diminishing from sickness and hardship; our clothing began to get very thin; we had none too much to eat, and plenty of work, both by night and by day, but there was no murmuring. We had as yet received no reinforcements, though the enemy had evidently been strongly reinforced.

Day after day passed without anything particular being done except trench work. Our men went at it with a will — without a whimper — wet through from morn till night, then lay down in mud with an empty belly, to get up next morning, perhaps to go into the trenches and be peppered at all day, to return to camp like drowned rats, and to stand to arms half the night.

The following letter was written from the

Camp before Sevastopol, October 27th, 1854

My Dear Parents,

Long before this reaches you, you will have heard that our bombardment has proved a total failure; if anything, we got the worst of it. The French guns were nearly all silenced, but our allies stuck to us well. But you will have heard that we have thrashed the enemy again, on two different fields.

On the 25th inst. they attacked our position at Balaclava. Our cavalry got at them — it was a grand sight, in particular the charge of the Heavy Brigade, for they went at them more like madmen than anything that I can explain; the Greys and Inniskillings (one a Scotch and the other an Irish regiment) went at them first, and they did it manfully. They rode right through them, as if they'd been a lot of old women, it was a most exciting scene. I hear that the Light Cavalry have been cut to pieces, particularly the 11th Hussars and the 17th Lancers. The rumour in camp is that someone has been blundering, and that the Light Cavalry charge was all a mistake; the truth will come out some day. The mauling that our Heavy Cavalry gave the enemy they will not forget for a day or two. I was not engaged in fighting but simply going down to Balaclava on fatigue. You will most likely see a full account of the fight in the newspapers, and I feel you will be more interested in our fight, which we had yesterday (the 26th). What name they are going to give it, I do not know. It lasted about an hour and a half, but it was very sharp.

The Second and Light Divisions had the honour of giving them a good thrashing, and I do not think they will try their hands at it again for a little while. We had not much to do with it; it was the 30th, 41st, 49th, and 95th that were particularly engaged, and they gave it to them properly. We supported them. The field was covered with their dead and wounded — our artillery simply mowed them down by wholesale. The Guards came up to our assistance, but they were not engaged more than they were at Balaclava.

We charged them right to the town. I heard some of our officers say they believed we could have gone into the town with them; but our noble old commander knew well what he was about. I mean Sir De Lacy Evans, for he commanded the field.

You must excuse this scrawl, as I must be off — I am for the trenches tonight. It is raining in torrents, so we are not likely to be short of water; but I am as hungry as a hunter. Don't be uneasy; thank God I am quite well, and we must make the best of a bad job. As long as we can manage to thrash them every time we meet them, the people at home must not grumble while they can sit by their firesides, and smoke their pipes, and say, 'We've beat them again!'

We begin to get old hands at this work now. It is getting very cold and the sooner we get at the town and take it the better. It is immensely strong, and looks an ugly place to take, but we will manage it some day. The enemy fight well behind stone walls, but let us get at them and I will be bound to say that we will do the fighting as well as our forefathers did under Nelson and Wellington. By the bye, our sailors, who man our heavy guns, are a tough and jolly set of fellows.

I shall not finish this letter until I come off duty.

October 29th

Well, I've got back to camp again, We have had a rough twenty four hours of it; it rained nearly the whole time. The enemy kept pitching shell into us nearly all night, and it took us all our time to dodge their Whistling Dicks [5], as our men have named them. We were standing nearly up to our knees in mud and water, like a lot of drowned rats, nearly all night; the cold, bleak wind cutting through our thin clothing (that now is getting very thin and full of holes, and nothing to mend it with). This is ten times worse than all the fighting.

We have not one ounce too much to eat and, altogether, there is a dull prospect before us. But our men keep their spirits up well, although we are nearly worked to death night and day. We cannot move without sinking nearly to our ankles in mud. The tents we have to sleep in are full of holes, and there is nothing but mud to lie down in, or scrape it away with our hands the best we can — and soaked to the skin from morning to night (so much for honour and glory)! I suppose we shall have leather medals for this one day — I mean those who have the good fortune to escape the shot and shell of the enemy and the pestilence that surrounds us.

I shall write as often as I can; and if I do not meet you any more in this world, I hope to meet you in a far brighter one. Dear Mother, now that I am face to face with death almost every day, I think of some of my wild boyish tricks and hope you will forgive me; and if the Lord protects me through this, I will try and be a comfort to you in your declining days. Good-bye, kind and best of mothers. I must conclude now. Try and keep up your spirits

And believe me ever

Your affectionate son,

T. GOWING, Sergeant, Royal Fusiliers

Notes

[1] Faugh-a-Ballagh: Gaelic for 'clear the way'.

[2] fifth, sixth, or seventh cuts: these were

techniques taught in sabre drill and were aimed at the head. Cavalry troops

used sabres as one of their main weapons.

[3] What he actually said was,

"Here goes the last of the Brudenells."

[4] 'neither of them was capped': neither gun

would fire. The reference is to the percussion caps that were needed for the

gun to be fired.

[5] Whistling Dicks: huge shells that made a whistling noise as they flew through the air.

Last modified 16 April 2002