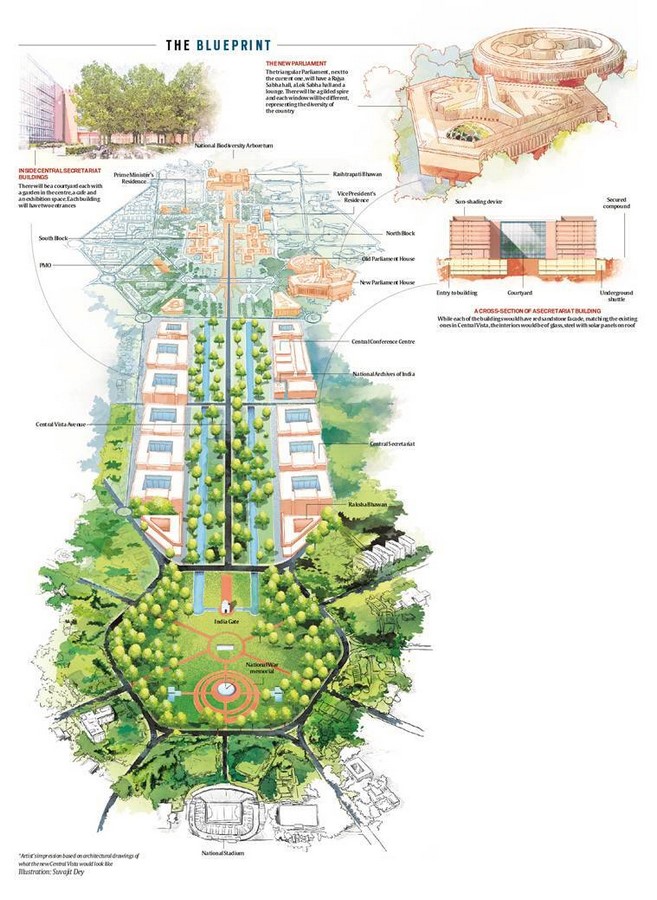

Work has now begun on a redevelopment project first proposed in 2019 by the Indian Government's Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. According to the Hindustani Times, the project "envisages a new triangular Parliament building, a common Central Secretariat and the revamping of the three-km-long Rajpath from the Rashtrapati Bhavan to India Gate and new residences for the prime minister and the vice president." Photography has been forbidden (itself a worrying sign), but some newspapers have caught the very beginnings of it, and the visible effects of the work, at this early stage, have shocked many in India and around the world. Eidya Pal is a young Delhi'ite who has written to us about the project, expressing her personal views on it. — Jacqueline Banerjee

he purlieus of India Gate and its nearby regions in the heart of New Delhi are being radically changed. India’s own government is about to demolish some key buildings that are the pride of the Indian capital, with a view to "revamping" the Central Vista, that is, the area near India Gate and Raisina Hill. There could hardly be a less appropriate time for resources to be deployed in this way, as the Covid pandemic continues to ravage the country. But there would never be a good time for such a redevelopment.

Left: Lutyens's India Gate War Memorial. Right: The Immortal Warrior Cenotaph beyond it. [Click on these images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.]

Master architects Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker designed the Central Vista in the 1920s. It is the area around India Gate that includes Rajpath — surely the most important boulevard in India — with nearby Parliament House, leading up to Raisina Hill. This is the incline on which the Rashtrapati Bhawan, originally designed by Lutyens as Government House, is located. The Central Vista further includes an ensemble of buildings and monuments such as the Central Secretariat and more. The designs of the buildings, structures and monuments are inspired by the Indo-Saracenic architectural style as practised widely in British India by earlier architects like Robert Chisholm, Henry Irwin and Frederic William Stevens. This loosely-defined but easily recognisable style showcases elements and motifs from all types of Indian architecture down the ages and across the subcontinent, and merges them with the western revivalist styles of the time, both Gothic and Neo-Classical.

Ensemble of Government buildings on Rajpath in New Delhi, India, by A. Savin (Wikimedia Commons, WikiPhotoSpace).

There were, inevitably, some difficulties in planning this massive project. For example, Lutyens was disappointed to find that, due to failings in the perspective drawings, only the dome of the Rashtrapati Bhawan could be seen from the foot of the incline (see Peck 268). Nevertheless, this could be said to have added a certain mystique to the view. There is certainly something very special about the Central Vista. It has long served as the symbol of democracy and governance in India, while India Gate itself has come to symbolise the whole country’s spirit of freedom and unity. Republic Day parades — and countless protests — have taken place here.

The current proposals, to change the area as part of a new Master Plan of Delhi, will insert oddly shaped buildings along both of its sides, forming a new "Common Central Secretariat." These will entirely disrupt the architectural layout of both the monument (India Gate) and its surroundings. The grand and spacious environment which has inspired Indians to come together as a populace, and, on occasion, to exercise their democratic rights and stand up for their beliefs, will be changed beyond recognition: the open lawns and serene pools on either side here will be replaced by a built avenue, robbing the Central Vista of its grace and grandeur, in the process obscuring its history and all that it means for the country.

A sketch by Surajit Dey explaining the proposed blueprint for the Central Vista at New Delhi (Creative Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0) via Wiki.

Worse still, to accompany the unnecessary creation of this crowded avenue, the government is razing other fine buildings to the ground. About a dozen landmark buildings including Vigyan Bhavan (the government's conference centre), Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, the National Museum and more are being demolished. These were built later than Lutyens' and Baker's, but they take their cue from the earlier work, and are also architectural masterpieces. For example the design of the Vigyan Bhavan building (by R.P Gehlote) is based on Indo-British architecture as well as directly on Mughal, Hindu and Buddhist architecture, acknowledging all our many-layered past history. The Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts has numerous times been a location where cultural programmes and gatherings have taken place, and distinguished people like his holiness the Dalai Lama and others have visited it. These are critical venues and form not only the architectural but also the cultural identity of Delhi. The older they get the more precious they are to all of us.

The prospective demolition of the National Museum is particularly troubling. Its first phase was completed only in 1989, and further developments have taken place since then. But it was purpose-built as a museum. Now its priceless exhibits are to be moved to the North Block, with its old-fashioned office spaces. No doubt attempts will be made to turn these into display areas, but it is very hard indeed to imagine it as a modern museum. Further, the Ashokan edicts lying outside in the present National Museum lawns, and the other huge archeological structural elements, will be at great risk during their relocation.

Other plans include the construction of a new office and residence for both the Prime Minister and Vice President, and a new parliament building just beside the old one. The original parliament building is very important to India and particularly to the Hindus, because its design was inspired by the very holy Chausath Yogini Temple in Morena, Madhya Pradesh. So again, there is a complete disregard for heritage here, in this case spiritual as well as architectural.

The present government is not the first to have considered the redevelopment of this area, but it is the first to have started implementing it. Among the reasons cited are that the original parliament building is old, and its capacity limited. These shortcomings could be addressed by a far less radical plan. But there may be a more fundamental reason: to remove any remnant of colonial legacy. However, the legacy here is thoroughly mixed, and, again, not only in terms of its architecture. Cultural and historical factors also come into it. The buildings and entire layout here communicate emotions of the bygone times that tell of both struggle and success. They symbolize not only the British Raj, and all that that meant for India, for good and ill, but the supplanting of it, after hard-won freedom from dependancy. Such legacies enrich a country and strengthen it. They are something of which to be immensely proud. Up until now, India has presented the world with some notable examples of the "retain and explain" strategy now being urged in the west (such as retaining the Mutiny Memorial on Delhi's North Ridge, but adding a new memorial board to it, celebrating those who died fighting bravely for the nation's freedom). Purposefully obliterating the country’s heritage is a sign of weakness and lack of confidence.

One of the long rectangular artificial lakes with fountains, amid lawns and trees, running either side of Rajpath. In this view from the road, India Gate itself is practically hidden by foliage on the left.

The destruction of cultural heritage is something that causes shockwaves across the borders of nations. Conventions have been ratified to preserve cultural heritage all around the world. Delhi's Central Vista is no exception. The lives of Delhi residents revolve around India Gate and this magnificent assemblage of buildings there. For decades now, they have spent some of the most memorable moments of their lives in that grand vast area in the central heart of the city. Its symmetry and spaciousness have been enjoyed by residents and visitors alike. Disrupting the Central Vista in the way proposed would be like building up Central Park in New York.

Opposition to the plans has been voiced at home and abroad by a range of people, from common citizens to academics and architects. Last year, for example, "60 former civil servants wrote to the prime minister about the scheme’s environmental impact on 'the lungs of the city.' 'Constructing a large number of multi-storeyed office buildings in this open area will create congestion and irreversibly change and damage the environment.' They added that the project would be an assault on the area’s architectural heritage, which is part of India’s cultural identity" (Debika Ray). International bodies and historians need to cooperate on this issue to prevent the damage and save the purlieus of India Gate and the heart of New Delhi.

Bibliography

"Centre busts myths around Central Vista, says 'claims mischievously exaggerated.'" Hindustantimes.com. Updated 6 June 2021. Web. 13 June 2021. [This expresses some different points of view.]

Peck, Lucy. Delhi: A Thousand Years of Building. An INTACH Roli Guide. 7th Impression. New Delhi: Roli, 2015. [INTACH is the increasingly active Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage.]

Ray, Debika. Apollo Magazine. May 2021. Web. 13 June 2021. [This also presents a variety of views.]

Created 13 June 2021