Apart from the first one, of the cover of the book under review, the images below all come from our own website. Click on them to enlarge them, and to find out more about them. — JB

In spite of the recent homage paid to Burne-Jones, for the centenary of his death in 1998, or more recently, in 2018 at the Tate London, it is commonly assumed that the artist was some sort of romantic dreamer, retired in a fantasy universe harking back to the Middle Ages, or rather to an idealised vision of the period, filtered through Pre-Raphaelite imagination. It is precisely such a watered-down image, associated with the greenery-yallery of the aesthetic generation, that Andrea Wolk Rager sets out to combat in his book, the result of years of work on Burne-Jones.

Considering that William Morris was his lifelong friend, whom the future “Sir Edward” met when they were both students at Oxford, it should not come as a surprise that Burne-Jones himself shared Morris’s political orientation and revolutionary aspirations. By focusing successively on examples of his production in various artistic mediums, Rager uncovers the “radical” character of Burne-Jones’s work, which challenged viewers on several levels. The most obvious form taken by this radicalism is the defiance of social and political hierarchies, and the attack against materialism. Some of Burne-Jones’s efforts also had a radical dimension on a purely artistic level, and possibly a religious dimension too.

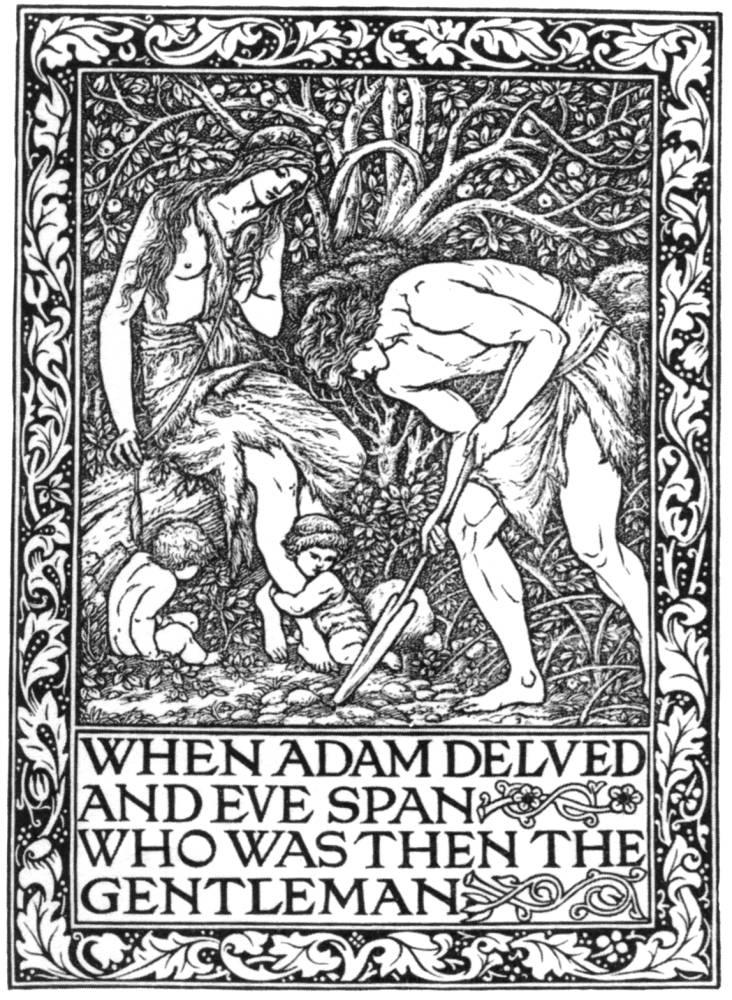

The first two chapters start from works whose radical message is easily accessible. In 1892, Burne-Jones produced the frontispiece for William Morris’s socialist novel A Dream of John Ball, a picture captioned “When Adam delved and Eve span.” In its full version (the second line of the couplet asks “Who was then the gentleman?”), the sentence was originally coined in the twelfth century, and was taken up as a rallying cry by John Ball’s followers during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. In 1857, Burne-Jones had already started depicting Adam using a spade and Eve carrying a distaff, for a stained-glass window, and he repeatedly came back to the subject, as a way to show that labour was not a curse but a means of redemption. Once associated with Morris’s book, “When Adam delved and Eve span” clearly became a form of anti-capitalist protest, but long before 1892, Burne-Jones wanted his art to help social awakening. In fact, he only gave up active political protest when he was disheartened by its apparent uselessness, but still hoped for an egalitarian future.

Left to right: (a) When Adam delved and Eve span, frontispiece to William Morris's A Dream of John Ball (1892). (b) King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid (1884). (c) George Frederic Watts's Mammon (1884-85).

The inversion of hierarchies is also the visible theme in King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid (1884). On this canvas, a poor and weak woman is shown in a dominant position over a rich and strong man. When the work was displayed in Paris, in the English section of the Universal Exhibition of 1889, it was recognised for what it probably was in the artist’s mind: a protest against the “material empire” (67), the phrase used by Burne-Jones in 1896 when he lamented the Boer War, the British empire being characterised by its military aggression and loss of spirituality. In Paris in 1889, King Cophetua was flanked by Watts’s Mammon and Hope, the former being another denunciation of rampant capitalism. (In 1884, it had first been exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery, one of those temples of privilege which Burne-Jones hated, as he wished his work to be enjoyed not only by the moneyed classes but by the population at large.)

Perseus and the Graiae on a panel, photographed with permission at the Tate exhibition of 2018/19.

The most radical aspect of the Perseus series of paintings commissioned in 1875 by Arthur Balfour for his London house was undeniably the fact that Burne-Jones initially planned to mix painting and sculpture, blurring the boundaries between decorative and monumental art, as well as the separation between word and image. Indeed, as witnessed by the only surviving example of the original project, Perseus and the Graiae (National Museum of Wales, Cardiff), four of the ten pictures were to be executed as carved and painted gesso panels, with texts in Latin filling part of the scene. This innovation was to be echoed by the paragone effect of some paintings which imitated sculpture in their rendering of textures. The Medusa myth is all about flesh turned into stone by the eyes of the Gorgon, but Burne-Jones also included allusions to the story of Pygmalion, since he originally wanted to depict Andromeda twice on the same canvas, first from behind on the left and from the front on the right, rotating like a statue on her pedestal, moving from stone into flesh like Galatea. The whole cycle, which remained unfinished when Burne-Jones died, would have been “a meditation on art’s capacity as a mirror on the world” (157).

The following chapter studies the mosaics designed for the American Episcopal Church of St. Paul’s Within the Walls, in Rome. Burne-Jones received the commission in 1881 and was glad to fill the building “with lasting, unsaleable pictures” (167). Not only did this work fit his desire to reach the people and to endure beyond the foreseeable collapse of Western civilisation, it also allowed him to join Ruskin and Morris in their ecosocialism. While The Annunciation took place in a barren desert, The Tree of Life offered a vision of Nature restored, just as Christ, in spite of his traditional position, was not a dead body affixed to a cross but a living God standing in front of a luxuriant tree and extending his benediction toward Adam and Eve in their postlapsarian universe. Taken together, the four mosaics planned for the arches and walls of the Roman church (beside The Heavenly Jerusalem a last one should have depicted the fall of Lucifer) would have formed a “perpetual, cyclical rise and fall across the nave . . . offering hope for the renewal and redemption of the earth to future generations” (203).

Left: Detail of mosaic at St Paul's Within the Walls, decorated 1881 onwards, showing Christ at the apex — "not a dead body affixed to a cross but a living God standing in front of a luxuriant tree and extending his benediction toward Adam and Eve in their postlapsarian universe." Right: Detail of a Burne-Jones stained glass nativity window in the Epiphany Chapel of Winchester Cathedral, installed in 1910.

Finally, Andrea Wolk Rager examines the various representations of the Nativity created throughout his career by Burne-Jones, from 1861 until 1898. “His interpretation of these subjects was profoundly informed by the doctrine of the Incarnation, which in turn became an egalitarian model for aesthetic creation and epiphany” (208). An obvious form of radicalism in these works (paintings, drawings, watercolours, tapestries, stained-glass windows) is the opposition between the Magi and the shepherds, the divine revelation making equals of them – just as Balthazar the African king is shown as the equal of the white kings. Burne-Jones’s visions of the Nativity can be interpreted as “a radical assertion of the Christian mandate to redress social inequalities” (245). Birth and death are gathered in the hint at the Lamentation over Jesus’s dead body in the very representation of a reclining Mary cradling the new-born baby in her hands; the idea of the Word made flesh is also expressed in “apocalyptic visions of the world simultaneously fractured and remade” (252), Burne-Jones finding opportunities to extend “his radical claim of unity from the natural to the social world” (261).

The Wheel of Fortune

(1875-83).

Rager concludes with The Wheel of Fortune, where the rich and mighty are shown to be humbled by the goddess. At the very bottom of the picture, the presence of a figure crowned with laurel and whose eyes are wide open could mean that “the poet may yet be able to awaken his fellows to the possibility of breaking the wheel itself” (269), rebelling against the injustice of the social order and the industrial devastation of the world. Founding her study on a thorough knowledge of the artist, Rager convincingly shows that, far from being escapist fantasies, Burne-Jones’s works used their own beauty as a form of protest against commodity culture, calling for awakening and transformation.

Bibliography

Rager, Andrea Wolk. The Radical Vision of Edward Burne-Jones. New Haven and London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Arts / Yale University Press, 2022. 336pp. £42.55 ISBN ISBN 978-1913107277

Created 18 November 2023