The photographs below were taken by the author at the press view of the exhibition, with two exceptions: the image of the book cover, and the reproduction of Flamma Vestalis. The latter comes from the images made available by the gallery for purposes of reviewing. [Click on all the images to enlarge them, and sometimes for more information about them.]

Sir Edward Burne-Jones's style is instantly recognisable — a compelling mix of graceful lines, tonal harmonies and symbolic resonance, within which the human element is raised almost to an abstraction. It is narrative art of a poetic order, quite different in impulse from Victorian genre paintings of historical scenes or domestic realism. Yet it found its way to a large public because, like his friends in the Pre-Raphaelite circle, William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Burne-Jones employed it in a variety of media. In fact, as Elizabeth Prettejohn points out in the opening essay of Edward Burne-Jones, the handsome book accompanying this exhibition, "almost without exception, the artistic ideas that generated this vast body of production originated in the realm of applied or decorative art" (p. 13). In his heyday, then, Burne-Jones's work appealed to the broad church of public taste — an apt metaphor to use of an artist whose stained glass designs can be seen in parishes throughout the country, and even beyond it.

Early Work and Draughtsmanship (Rooms 1 and 2)

Ladies and Death (1860), a painted panel for an upright piano made by Frederick Priestly, in Room I.

The first surprise of the long-awaited Tate exhibition is the sheer quality of Burne-Jones's early work. The basic facts of his apprenticeship years might be familiar — his transition from industrial Birmingham, where he was born and brought up, to Oxford, where he began by studying theology, but soon fell into the company of Morris and Rossetti. But (to take one example among many in the exhibition's first room) the piano panel shown above, painted before he became a founder member of Morris & Co., already bears the hallmarks of his maturity. Several women are seated in a row, two making music, the others lost in it, with another figure leaning into the scene from the right; but at the very door of the room, on the left, looms the spectre of death, crowned, robed and bearing his lethal scythe. Appropriately enough, the posture of the women and the range of the palette seem gradations on a scale, the whole provoking reflection on the meaning of art and human existence. Although the gold highlights stand out as brightly as in some of his early watercolours, here from the start is the emphasis on composition, to which the individual figures seem subordinate; the languor or stillness that characterises these figures and gives them that symbolic plangency; the generally restricted palette; and, above all perhaps, the sense of beauty, culture and innocent pleasure assailed. Early as it is, it serves in many ways as a taster for the much later and more sombrely coloured Briar Rose sequence of 1874-90, which occupies Room 6.

Triptych (1961): The Annunciation and the Adoration of the Magi (1860), also in Room I.

Another early but characteristic work in Room 1 is the beautiful triptych above, receiving its first showing after a long conservation process. Morris has posed for the kneeling King, and Jane Morris for Mary. Even the floral elements here would figure again and again throughout the mature oeuvre. Some of Burne-Jones's fine pen-and-ink drawings, and watercolours, are also on display here, as are several stained glass panels, such as The Good Shepherd (1857-61), and his ceramic tile portrait of Chaucer, borrowed like several other items from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Again, despite the variety of media and subjects, the hand is unmistakable. There is even, already, The Wine of Circe (1863-69), the watercolour which, says curator Alison Smith in her chapter on Burne-Jones's early work, "sealed his reputation as a painter of rare imagination" (66).

The cumulative effect is impressive, and continues to build from one room to another. The special emphasis of the next room is on Burne-Jones's draughtsmanship, and it includes a range of preparatory studies for later work. Many of the smaller ones are breathtaking in their drapery details, while the larger ones (without the distractions of close detail, colour or even their visionary quality) are striking in their composition.

Venus Discordia (c.1872-73) catches everyone's eye in Room 2.

Venus Discordia (c.1872-73) stands out here, not least because, despite being unfinished, it has an elaborate classical frame. This work was started as a complement to Venus Concordia, which shows Venus seated, sweetly pensive, with the Three Graces beside her. Here, however, she sits dispiritedly, witness to a scene of violence involving the four vices: Anger, Envy, Suspicion and Strife. Burne-Jones was much influenced by his trips to Italy, and, according to the gallery label, this shows the particular influence of artists, including Michelangelo, whose work he had studied on his latest visit of 1871. The subject itself is important too, helping to refute the criticism of those who see Burne-Jones's pursuit of beauty as a "dishonest evasion" of reality (see Tromans 41). In another way, as well, this room supplies a more rounded picture of Burne-Jones: in her role as curator, Smith has fitted in some of his comic sketches and caricatures — though not one particular favourite, which speaks of the usual frustrations of "early career" artists: The artist attempting to join the world of art!

Exhibition Paintings and Portraits (Rooms 3 and 4)

Left: Three paintings are seen here: King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid (1884); Laus Veneris (1873-78); and The Golden Stairs, 1880. There is also a partial view of Love and the Pilgrim, 1896-97. Right two: Flamma Vestalis (1896), 1079 x 374 mm., from a private collection. What a difference a frame makes....

The exhibition pictures come next in Room 3, just a dozen, but dazzling. There is no mistaking that here we are entering the realm of the fine rather than applied arts. The paintings include, as well as those shown above, The Beguiling of Merlin (1872-77), Laus Veneris (1873-78) and The Wheel of Fortune (1883), this last brought over to the Tate from its home at the Musée d'Orsay. The Edinburgh Review critic of 1899, in a Masters in Art collection of critiques of Burne-Jones's work, complains that some people find this artist's world of "imaginative emotion" too far removed from reality (25). Yet only the least susceptible could resist responding to that world when surrounded by it on all sides. As another contemporary critic noted, "if few great artists have wandered farther, both in intention and fact, from the presentation of the truth of the broad and multitudinous actualities of the world around them, few have diverged less from the representation of truth to their own individual imaginative vision" (Master in Art, 28). One of Smith's own chapters in the accompanying book is on these exhibition paintings, and she helpfully reminds us that "[a]nother way in which Burne-Jones’s pictures touched a broad audience was through reproductive photographs and prints" (140) — which naturally boosted his reputation and influence, both at home and abroad.

Not even Burne-Jones's relatively few portraits escaped a colouring of his highly individual vision — natural enough in view of his own opinion that "[t]he only expression allowable in great portraiture is the expression of character and moral quality, not of anything temporary, fleeting, accidental" (Burne-Jones 140; also quoted by Charlotte Gere in her informative chapter on the portraits). Another triumph of the exhibition is to bring together in Room 4 twelve of his comparatively few portraits, which are normally widely dispersed among private collections and galleries as far away as Australia. They tend to be idealised, soulful, like the one of his daughter Margaret in Flamma Vestalis of 1896. She is posing here as a vestal virgin. Yet the portrait does not differ greatly from an earlier one in which she is just herself, seated in a blue dress again (her favourite colour) with a round Van Eyck-type mirror behind her head like a halo. There is, in short, the same spiritual cast in both. It is what her father divined in her, expressed with a father's deep affection, and no doubt with his concern for the preservation of her virtue: Margaret is also the model for the sleeping princess in the Briar Rose

Series Paintings (Rooms 5 and 6)

Left: Enveloped in a dream: two paintings from the Perseus sequence in a corner of Room 5, showing the first in the sequence, Perseus and the Graiae on the left, and the Calling of Perseus on the right. Right: Perseus and the Graiae, relief panel on oak.

After the portraits, which are mostly small in scale, Rooms 5 and 6 plunge the visitor back into the Burne-Jones world of large themes and large works on large subjects — quest, trials, doom and not-quite-triumph, all reassembled with some in-filling of cartoons, oils and texts to make up the full sequences of the two great narrative mural cycles for which he is probably best known.

Room 5 deals with the Perseus series, illustrating on a sumptuous scale the mythical story of the Greek hero's quest for, and slaying of, the Gorgon Medusa, and his rescue of Andromeda from a cruel death. It had been retold by Morris in his poetic rendering of such tales in The Earthly Paradise (1868), and was fundamentally an illustration project. Again, the works have been assembled from places as far apart as Germany and Southampton, but the original commission, which came from the future Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, was very much a domestic one: the series was to decorate the walls of Balfour's London drawing-room. Of the ten subjects originally planned, only four were worked up into oil paintings, and of the four wooden panels intended to complement them, only one was completed. But, supplemented by studies, here on display is much of what Burne-Jones had envisaged, and the effect is as immersive as he could have wished for. The wooden panel shown above, with its silver and gold leaf, is unique in that it has a Latin summary of the legend above the main composition. The effect is highly original: as Prettejohn explains, the panels were planned as "a particularly innovative part of the design not only in their mixed media, but also in the stylisation of their figures, silhouetted in the shallowest of relief against a wood-grain pattern that makes no attempt to represent a natural setting" (183). Perhaps because it was not well understood out of context, the panel was poorly received when shown at the Grosvenor Gallery, and no more were made.

The Rose Bower (128 x 231 cm.), from the Faringdon Trust, with two infill panels either side.

Room 6 brings together the four paintings of the Briar Rose sequence, along with ten "infill" panels, all from the Faringdon Collection — they had originally been acquired by the future Lord Faringdon. However, this series too was never complete, at least in Burne-Jones's own mind, insofar as he went back to some of his discarded canvases later, and set to work on them again (see Prettejohn 176). There is a particular sense of hiatus here too, since, even on the brink of achievement, the artist withholds the key moment — that climactic, awakening kiss. Here again is an immersive experience, the somnolence of the court lending it more of an ethereal quality.

Burne-Jones as a Designer (Room 7)

Left: The Graham Piano, ebulliently painted for Frances Graham in 1879-80. Right: Adoration of the Magi tapestry.

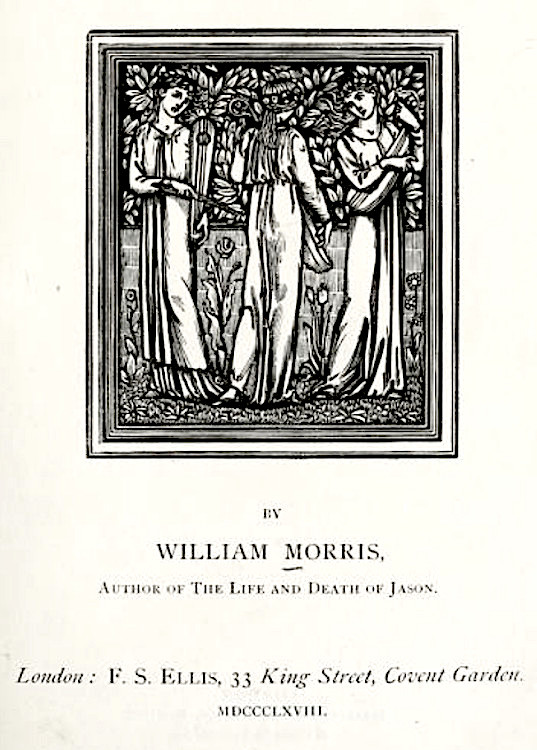

With changing fashions in the art world, particularly the pervasive influence of French Impressionism, Burne-Jones's reputation in the fine arts slumped: "the Burne-Jones collection disappointing & depressing, so many long faced women," wrote Lady Gregory late in the century (10). The Tate's long-awaited retrospective therefore performs a great service by drawing out so fully the unique artistic vision that informs his large and diverse output. It ends on a high note, too, because arguably this last room makes the greatest impression of all. There has never been any doubt about Burne-Jones's flair for designing stained glass, embroidery and tapestries in churches, and he clearly enjoyed painting furniture, as well as helping to produce beautiful books — and some brilliant examples of all these are on display here. They range from the centrepiece shown above, a Broadwood piano that he decorated ebulliently for Frances Graham, to his vignette for the frontispiece of Morris's Earthly Paradise. Does it matter that these glorious pieces are applied rather than fine art?

Left: Stained glass panel, Elijah in the Wilderness. Right: Frontispiece of Morris's The Earthly Paradise, with a woodcut vignette by Burne-Jones.

As shown by the much earlier piano panel featuring Ladies and Death, Burne-Jones knew from the start that the world he was creating from his imagination was a world under siege. Far from ignoring the realities of life, he used his art as a personal rebuttal of them, or at least a bulwark against them: they were the kind of works with which one could truly surround oneself. In this respect, he shared in the ethos of the Arts and Crafts movement, while his reputation in the fine arts, where he had close and obvious affinities with later developments, particularly the Aesthetic and Symbolist Movements, now rests largely on his exhibition work. Yet, as this marvellously multi-faceted exhibition revels, his vision unites all his endeavours. They all count. Surely not even Lady Gregory could have remained untouched by such a display. The accompanying book follows the layout of the exhibition closely and is richly illustrated, making it at once an ideal companion to it, and a souvenir to enjoy and read more closely as time permits.

Related material

Bibliography

[Book under review] Smith, Alison, ed. Edward Burne-Jones. London: Tate Publishing, 2018. 240pp. ISBN 978-1-8. Pbk. £25.00 (Available at all good bookstores and online here.)

Burne-Jones, Georgiana. Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, Vol. II. London: Macmillan, 1904. Internet Archive. Contributed by Brigham Young University. Web. 28 October 2018.

Gregory, Lady Augusta. Lady Gregory's Diaries, 1892-1902. Ed. James Pethica. Gerrards Cross, Bucks: Colin Smythe, 1996.

Masters in Art: A Series of Illustrated Monographs: Burne-Jones. Vol. 2 (July 1901). Boston: Bates and Guild Company. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Getty Research Institute. Web. 1 November 2018.

Morris, William. The Earthly Paradise. London: F. S. Ellis, 1868. Internet Archive. Contributed by Duke University Libraries. Web. 1 November 2018.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. "The Series Paintings." Smith 169-95.

Tromans, Nicholas. "'Girlish Dreams': Burne-Jones in the Twentieth Century." Smith 35-41.

Created 1 November 2018

Link added 19 November 2018