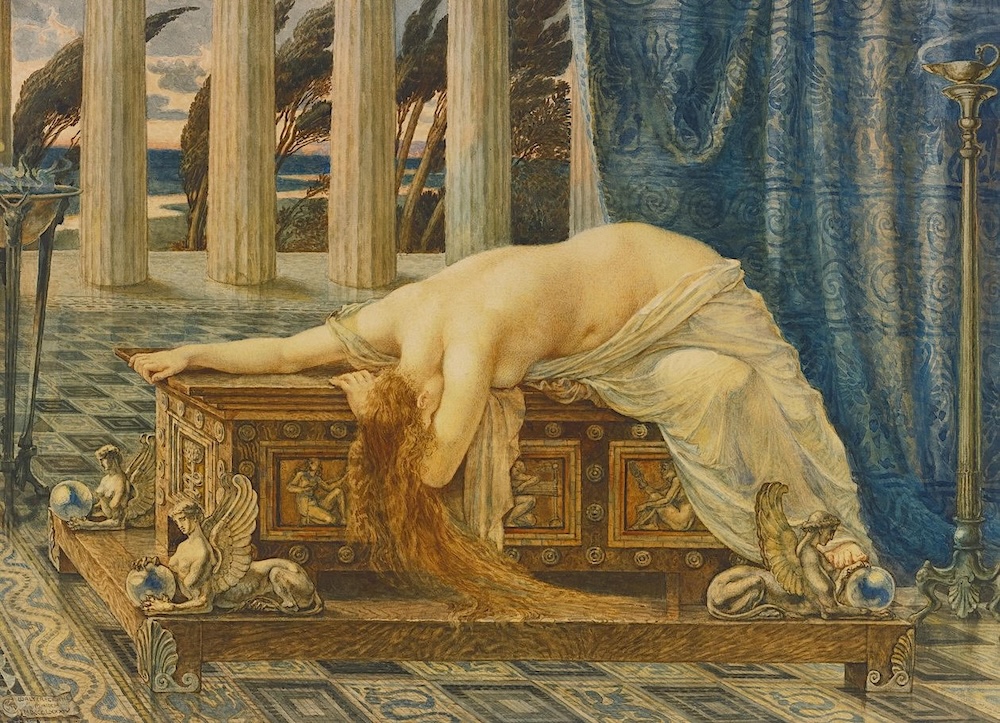

Pandora, by by Walter Crane, RWS (1845-1915). 1885. Watercolour on paper. 21 x 29 inches (53.3 x 73.6 cm) – sight. Private collection. Image courtesy of Sotheby's, New York. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Pandora was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1885, no. 16. In Greek mythology Pandora was created by the gods as a punishment to mankind for Prometheus stealing fire and presenting it to humanity. Zeus gave Pandora to Prometheus's brother Epimetheus and presented her with a box that he told her never to open. Her curiosity eventually got the better of her, however, and she opened the box thereby releasing all the evils and miseries of the world including sickness, sorrow, strife, and death. In most versions of the story, as Pandora quickly tries to close the box, hope gets trapped under the lid and doesn't escape, thereby providing some comfort to mankind as it confronts these hardships. In Crane's watercolour the partially clothed figure of Pandora is shown in a state of anguish lying on the box she was presented by Zeus, her hands clutching the lid after she has brought about disaster by opening it. The box lies on a wooden stand, surrounded by four sphinxes as ornaments, and the stand sits on a beautiful mosaic floor. Isobel Spencer has noted that "[t]he delicate colour and setting of a colonnaded hall with tossing cypresses beyond made this a pleasing work in spite of Pandora's abandoned posture which was condemned by critics for being as formless as a jellyfish" (128-29).

Morna O'Neill has given her own interpretation of this picture:

Crane's watercolour presents the grieving Pandora draping herself over the casket. She is placed in an elaborately decorative and theatrical setting. The box itself is elevated on a platform, and its every sheen and surface is carefully rendered. An inlaid end panel makes reference to another temptation story - the biblical tale of Adam and Eve - by showing a serpent intertwined with the tree of knowledge of good and evil. The three visible side panels depict the Three Fates (or moirai): Clotho spins, Lachesis weaves or measures the thread, and Atropos cuts the thread of human life. Each corner of the casket is guarded by a regal sculpted sphinx, with images of the mythic creature - the most prominent of the "minatory emblems of austere heraldry" - appearing as well on the floor, the curtain, and the casket…. Pandora is a crucial expression of what Crane would later term the "identical" forms of decoration and symbolism. In this painting, inspired by his study of Renaissance book illustration and classical ornament, he employed the emblem to unite symbolic purpose and decorative effect. [115-116]

Contemporary Reviews of the Painting

Critics reviewing the Grosvenor Gallery exhibition of 1885 were in general much more impressed by Crane's other submission that year, the large oil painting of Freedom. The Artist merely remarked about the smaller watercolour: "The imaginative vein of the school [Burne-Jones] is well sustained by Walter Crane in his large canvas Freedom and the wonderfully sympathetic Pandora" (132). A reviewer for The Builder pointed out the awkwardness of the figure of Pandora: "Mr. Crane's other work, Pandora (16), is hardly a success; the attitude of the figure is rather painfully contorted, and the drawing of the head, bowed forward, so as to hide the face, is not quite successful" (610).

The critic for The Illustrated London News found none of the works of the principal followers of Edward Burne-Jones was sufficiently interesting to arouse his "flagging interest" in this group including "neither Mr. Walter Crane in his Pandora (16), prostrate on a chest into which she might enter in search of Hope, or in his still more exaggerated Freedom" (544). W. E. Henley in The Magazine of Art was one critic who actually preferred Crane's smaller watercolour: "Mr. Crane's Pandora is, so far as we can recall, the best of his pictures; it is a riddle not easy to read, but it is very choice and pretty decoration" (351). Henry Blackburn simply describes the picture: "Golden hair, pearly tints in drapery; marble palace, inlaid pavement and blue curtain; a brazier burns on the left; marble columns; evening sky, and blue distance; cypresses bending in the wind" (7).

Crane was not the only Victorian artist to portray Pandora opening either a box or a vase, with others such as D.G. Rossetti, Laurence Alma-Tadema, J.W. Waterhouse, J.D. Batten, and Henrietta Rae taking up the same subject.

Bibliography

Blackburn, Henry. Grosvenor Notes. London: Chatto and Windus (May 1885): no. 16, 7.

"The Grosvenor Gallery." The Artist VI (1 May 1885): 132-33.

"The Grosvenor Gallery." The Builder XLVIII (2 May 1885): 609-10.

"The Grosvenor Gallery." The Illustrated London NewsLXXXVI (23 May 1885): 544.

Henley, William Ernest. "Current Art – I." The Magazine of Art VIII (1885): 346-52.

"The Myth of Pandora's Box." Greek Myths. Web. 25 November 2025. https://www.greekmyths-greekmythology.com/pandoras-box-myth/#what-does-it-symbolize-in-greek-mythology

O'Neill Morna. Walter Crane. The Arts and Crafts, Painting, and Politics, 1875-1890. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010. 115-116 & 121-22.

Sotheby's Designer Showcase. New York: Sotheby's (April 20, 2015): lot 165. https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2015/sothebys-designer-showhouse-n09333/lot.165.html

Spencer, Isobel. Walter Crane. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc., 1975.

Stephens, Frederic George. "Fine Arts. The Grosvenor Gallery." The Athenaeum No. 3000 (25 April 1885): 540.

Created 25 November 2025