The Fine Art Society, London, has most generously given its permission to use information, images, and text from its catalogues in the Victorian Web, and this generosity has led to the creation of hundreds and hundreds of the site's most valuable documents on painting, drawing, sculpture, furniture, textiles, ceramics, glass, metalwork, and the people who created them. The copyright on text and images from their catalogues remains, of course, with the Fine Art Society. [GPL]

No one quite understood why art should flourish in grimy Glasgow at the turn of the twentieth century. Even in eulogies on the ‘second city of the Empire’ there was a sense of wonder at how this could be – how a group of painters known as the Glasgow School should hold such sway in the foreign academies, Salons and secessions of western Europe and North America. Forty years earlier the freakish paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites had been regarded as no more than a curiosity at the first great Paris Exposition Universelle, and now a Scots group whose pictorial etiquette was distinctly un- English, led the mainstream. London critics were askance. It was not just that the ‘Glasgow Boys’, as they were familiarly styled, studied the advanced art of France and Holland, it was that in suave, stylish pictures such as John Lavery’s The Tennis Party they brought new life to the concert of fin-de-siècle art styles. At the same time, this firm grasp on modernity contrasted with the bold, brutishness of pictures like George Henry and E.A. Hornel’s The Druids, Bringing in the Mistletoe. In the 1890s, there was less of a consensus on the direction painting would take than there had been in the mid-century, and Glasgow, before the advent of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and so-called l’art nouveau, spanned the field and scooped medals and prizes in Europe and America.

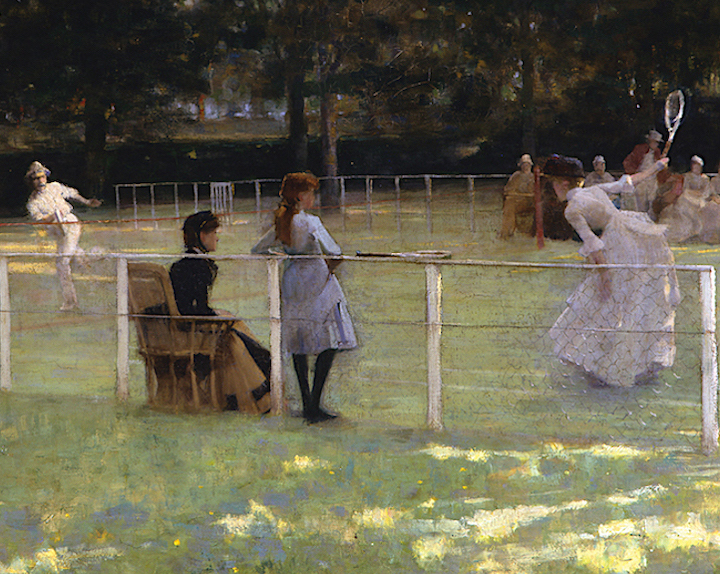

John Lavery, The Tennis Party (detail), 1885, Aberdeen Art Gallery.

In their beginnings, young painters from the west of Scotland were no more exceptional than those from elsewhere in the British Isles. They went through the filtering processes of local art schools and exhibitions, and only if they survived, would they join the migrant student shoals who drifted between Montparnasse and Montmartre. No one contested the ascendancy of Paris around 1880. Such was its popularity that the teaching ateliers were overcrowded. In noisy, smelly, overheated rooms in front of a naked model, the Scots rubbed shoulders with the French, English, Irish, American, Eastern European, Scandinavian and other expatriate students. They were part of the rowdy ‘anglais’ brigade and their only gripe was that restaurateurs on the Left Bank dismissed their staple porridge as something only to be applied to boils. Lavery, an Ulsterman coming from Glasgow, recalled that his teacher, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, having established that he was not a rich Irish landlord, told him his drawings were wooden and instructed him to look for character and tone. Studying form, proportion, space and three dimensions was not of itself a radical curriculum, but the competitive atmosphere and the ruthless criticism of the Salon masters inevitably sorted the oats from the chaff.Illustrated journalism, photography and the rapid dissemination of images created new conditions for the production of paintings around 1880 and the most controversial works responded to the call for documentary accuracy. A revered young master like Jules Bastien-Lepage achieved the ultimate naturalism and was hailed by Emile Zola, no less, as superior to the Impressionists because he knew how to ‘realize’ his impressions. He impressed ‘St Mungo’s merchant princes’, Glasgow’s avant-garde collectors, housed in the palatial villas of Kelvinside. He exposed art to the open air and brought it back into the studio. Notes and studies, along with photographs and other visual evidence, had a greater purpose in réalisation. And as the techniques to achieve verisimilitude became more sophisticated, the imagination was reined-in to the here and now. Lived experience, rural rather than urban, swiftly became the criterion. The heady debates fuelled by beer and tobacco, spilled over from the denizens of the quartier latin into the countryside – north and west to the Seine Valley, east to the Marne, and south to Barbizon, the Fontainebleau forest, as far as the tiny village of Grez-sur-Loing.

The artists’ artists’ colony at Grez had been founded in 1875 by a group of students from Carolus Duran’s atelier that included Robert Allan Mowbray Stevenson, the cousin of Robert Louis Stevenson. RLS became the early chronicler of the village and its chief publicist. Within a couple of years it was attracting other Scots such as Robert Campbell Noble in 1877 and Arthur Melville in 1878. Melville’s Paysanne à Grez is almost a thesis-picture demonstrating the new plein-airisme currently sweeping the studios. It was an ‘impression’, a stage in the process of realisation, which only in later years, with the ascendancy of the Impressionists, was recognized as a legitimate end in itself. The Scots, William Kennedy, Alexander Roche and Thomas Millie Dow patronized the Grez hotels, but the most important habitué of the village on the Loing was Lavery. In 1883 and 1884 his ‘impressions’ were successfully converted to major works – to panoramic riverscapes such as The Bridge at Grez, to woodland scenes like La Rentrée des Chêvres, and garden pictures, On the Loing, An Afternoon Chat – all of which became favourite exhibitionpieces typifying the new, radical naturalism of young west of Scotland painters. ‘Art’ as one of the Glasgow students triumphantly recalled ‘was the only thing worth living for’.

James Guthrie, To Pastures New (1882), Aberdeen Art Gallery.

The raucous enthusiasm of the quartier was undimmed by the Glasgow drizzle. Under its lowering skies, the Boys congregated at the end of 1884 determined to change things. James Guthrie with pictures such as To Pastures New raised the standard. There was nothing sentimental about his goose girl; the heather hills which might have set the national scene, were banished. This was new painting of the most impressive kind. Unlike Lavery, Roche, Kennedy, Walton and Melville, Guthrie may not have endured the rough and tumble of the ateliers, but he caught the mood of the time and his early success convinced others that the imperial city was the place to be. He was even prepared to write to The Glasgow Herald , upholding the common cause of the ‘sincere art workers’ who were his friends. The occasion was provided by the great International Exhibition to be staged at Kelvingrove in 1888 in which local industry was matched with that of the rest of the world. The city was not however, explicitly valued for itself. There was no Canaletto to paint its Gothic Cathedral, its ‘Greek’ Thompson classicism, much less its ‘wynds’ and ‘closes’. The rich hinterland of high garden walls concealing the middle classes was more immediately beckoning, and in such a setting, on the banks of the Cart, Lavery painted the newly fashionable game of lawn tennis that in ten years had swept the country. It was ‘no special occasion’ recalled the principal player, Alex MacBride, just a ‘very fine picture’ for which he and his friends posed from time to time. As you walk up to the open gate marking the corner of the court, all eyes are on the game. The picture was awarded a ‘wooden spoon’ by the readers of the Pall Mall Gazette when it was shown in London, but two years later, the enlightened Parisians gave it a medal – the first to be awarded to a Glasgow Boy. George Moore, then dabbling in art criticism, declared it ‘a beautiful thing’ and a ‘permanent source of happiness’ when he found it in the Salon.

Why was London so out of step? Two years before Lavery placed his picture in the Royal Academy, Ruskin in one of the last coherent flashes from his fell-side fastness, declared the national school ‘in peril’. Every young painter was heading back from Paris speaking tongues that the erstwhile Pre-Raphaelite propagandist could not accept. The suave modernity of Cartbank and Helensburgh was not a thing to celebrate. The Boys were painting the very class of people who were their patrons. Their modernity was an ugly thing. And although their professional and industrialist backers at first were taken with kailyard paysanneries, they ultimately longed to see themselves and their pretty daughters – in the street, in the garden, visiting an exhibition or, fancydressed, for a for a costume ball – as the true subjects of contemporary art. With flashing brushes, the Glasgow School painter was a reporter, and his finest works were witness statements. The couples linking arms in Lavery’s view of The Glasgow International Exhibition, 1888, were undoubtedly there at the very hour it was painted.

But this vivid engagement with the passing scene was not all that Glasgow painters could offer. When they delved into history it was to find what one painter referred to as ‘the soul of Scotland’ – that poignant moment when Mary, Queen of Scots after Langside, stares at defeat in the ashes of the fire, or when the ancients solemnly process through the sunlit snow in George Henry and Edward Atkinson Hornel’s The Druids, Bringing in the Mistletoe . This extraordinary canvas has still to release all its secrets – the ‘cup and ring’ marks found on Galloway stones, the Celtic spirals taken from the Battersea Shield, and the ‘primitive’ faces, recalling that back in the late 1880s, the popular imagination was fired by Red Indians on tour with William Cody’s Wild West Show. With its gold embellishments, surface patterns and bright colour, the picture introduced a new principle – the decorative. The wan, wishywashy followers of Burne-Jones were blown away.

Travel too, in the age of Cook, Murray and Baedeker, was something the Glasgow Boys were good at. Not only did they follow their pictures to the exhibitions in Europe and the United States, but they were also Orientalists and artist-adventurers. Henry and Hornel, in the spirit of Phineas Fogg, steamed off to Japan. Crawhall, Lavery, Mann and others established a colonial outpost in Tangier, long before it became the haunt of gay writers and Melville trekked across the sands on horseback to Baghdad. In this day of themed waterway holidays, it may not seem so extraordinary to take a barge along the Ebro in Northern Spain, but Melville did this in 1892, noting his experiences in vivid oil sketches, which in one notable case, was transformed into a lunar landscape punctuated by the blue ghosts of Monet’s poplars. On the distant hillside – he would have to squint to see it – was a mule train carrying Contrabandista, and with it, the frisson of rls’s adventures. But this was no graphic novel; its lush, sensuous swirls of paint ushered in a new, ‘Post-Impressionist’ sensibility, long before the term was coined.

James Lavery, Night, Tangier. Oil on canvas, 25 x 30 inches; 63.5 x 76.2 cm. Signed. Provenance: Private Collection, Scotland. Exhibited: London, Royal Academy, 1911, no. 57.

Everywhere but Edinburgh and London, the Boys were international stars. In the nineties they faced down their opponents. Castigated by the Scottish Academy’s president for their brand of ‘Impressionism’, they nevertheless supplied the only pictures that made its exhibitions worth visiting, and it was to its detriment that the radical London-based New English Art Club rejected their work. It was not so with succeeding generations who took to Montparnasse a freshness and freedom of handling that placed the Scottish Colourists in the vanguard of Fauvism. This was part of the artistic ferment in the seething city that by the turn of the twentieth century was responsible of nearly a third of the world’s shipping, much of its cloth and a good proportion of its refined sugar. The engine room of the Empire may have incubated strange flowers, but none was more proud of its blooms. Its painters were recalled in 1899 to portray Glasgow’s place in ‘general history of human culture from the dawn of intelligence in the naked savage … to the modern epoch of the development of the higher arts …’ amidst the riotous marble pilasters and ‘electroliers’ of the City Chambers. Roche’s St Mungo pulling a lost ring from the mouth of a salmon, plucked from the Clyde, represented its legendary Christian founding, while in the ‘modern epoch’ shipbuilders toil in the Clydebank yards in Lavery’s mural (see below).

Painters who had made history, became its servants and grimy Glasgow was their arena.

John Lavery, Modern Glasgow, 1900, City Chambers, Glasgow

References

McConkey, Kenneth. Lavery and thr Glasgow Boys. Exhibition Catalogue. Clandeboye, County Down: The Ava Gallery; Edinburgh: Bourne Fine Art; London: The Fine Art Society, 2010.

Last modified 5 October 2011