The paintings shown below were photographed at the exhibition by the author, with the gallery's permission, for the purpose of this review. Because of our time frame, the works discussed here all come from the Fleming Collection. Click on the images to enlarge them, and usually for more information about them.

The Lightbox is a cultural hub in Woking, Surrey. Opened in 2007, it is tucked away near the Basingstoke Canal, but only a short walk from the centre of town. Despite its intimate feel, it includes a local history museum and ample space for visiting exhibitions. Its current show, running from 23 April-3 July 2022, presents highlights from two different but complementary sources: the Fleming Collection, which focuses on Scottish Art, and the Ingram Collection of Modern British Art, which follows developments in British art from the twentieth century onwards. Both have some exceptional works not easily seen — especially not together in one show. It is a rare privilege to encounter them locally, in this airy, welcoming ambience.

Robert the Bruce, by

George Jameson, 1633.

Expectations are reset from the very start. Instead of a majestic stag or Highland cattle looming from the mists, visitors are greeted by a dynamic portrait of Robert the Bruce. Not for nothing was the artist George Jameson (1587‐1644) considered "the Scottish Van Dyck." Looking over his shoulder, features framed by bushy ginger hair and whiskers, and with light glancing off his helmet and armour, Jameson's Robert the Bruce is fiery and alert, a man ready for anything. The portrait captures the indomitable spirit that led the Scots to victory against great odds at the Battle of Bannockburn. This was an inspired choice for the first section of the exhibition, "Phoenix from the Ashes," announcing the reinvigoration of Scotland's art scene after the ravages of the Reformation.

Thomas Faed's The Last of the Clan, 1865.

Just a little further on in the gallery, a work by the Victorian artist Thomas Faed is impressive in a very different way. Faed is a past master at eliciting sympathy, but he outdoes himself in The Last of the Clan. Here, he presents a wretched and recent episode in Scottish history, to epic effect. An emigrant ship is about to be cast off, during the notorious Highland Clearances. The ship itself is left to our imagination: the focus is not on the brave menfolk setting off to find work in other lands, but on the older and younger folk, the parents, wives and children, left desolate on the quay. The proud Scottish spirit in this instance is not theirs: these are broken people; it is the artist's, as he upbraids the English for their injustice by graphically conveying the misery it caused.

Migration has been a huge part of the Scottish experience, and it has not been passed over here. Yet the country's wrenching loss has often been the larger world's gain, and at home, in more recent years, immigration has helped to compensate for it. The exhibition is arranged thematically, not chronologically, and nearby in this second section ("Lost Idyll") there is Iman Tajik's Can You Hear Me 1 of 2015, which confronts the viewer with a refugee. (This work can be glimpsed in the gallery view top right.) The man's face, unlike Robert the Bruce's, is partially hidden. But his rumpled T-shirt, bearing the legend, "Highlands Club," and snatches of other words associated with Scotland, says much about his longing for a new beginning after the traumas of the past. Tajik is based in Glasgow now, but his own experience as a refugee is reflected here. Looking positively at the back-and-forth flow of people, another contemporary artist, Barry McGlashan (b. 1974), depicts tiny migrant birds perching here and there on the branches of a tree, outlined against a great full moon. McGlashan's Painting in Defence of Migrants (2021), on a small, tile-like panel, is striking in its simplicity and immediacy, and the message conveyed by its title is heartening.

Left: William Orchardson's Ophelia of 1874. Right: Arthur Melville's The Highland Glen of about 1893.

Despite the thematic arrangement, there is a strong sense here of the evolution of Scottish art. John Knox's rose-tinted traditional landsape of about 1816, with its pockets of close detailing View of the Clyde, from Faifley and Duntocher, appears in the first section. In the third, "Painters of the Modern World." William Orchardson's Ophelia of 1874 is unmistakably Victorian in feel: she is a waif, almost a wraith, her white dress remarkable in its filmy flimsiness, her lost look demonstrating the inwardness for which Orchardson's later work is praised. More daring kinds of innovation follow, both in subject and technique, from the Glasgow Girls and Boys, the Scottish Colourists, and other highly individual artists like Arthur Melville and Sir John Lavery. All were driving through and over the old conventions. The distance they travel can be measured by comparing that early nineteenth-century almost topographical View of the Clyde by Knox to Melville's The Highland Glen of the nineties, with its conjunction of cloud, mist and pooling light (or possibly autumn colours in the trees).

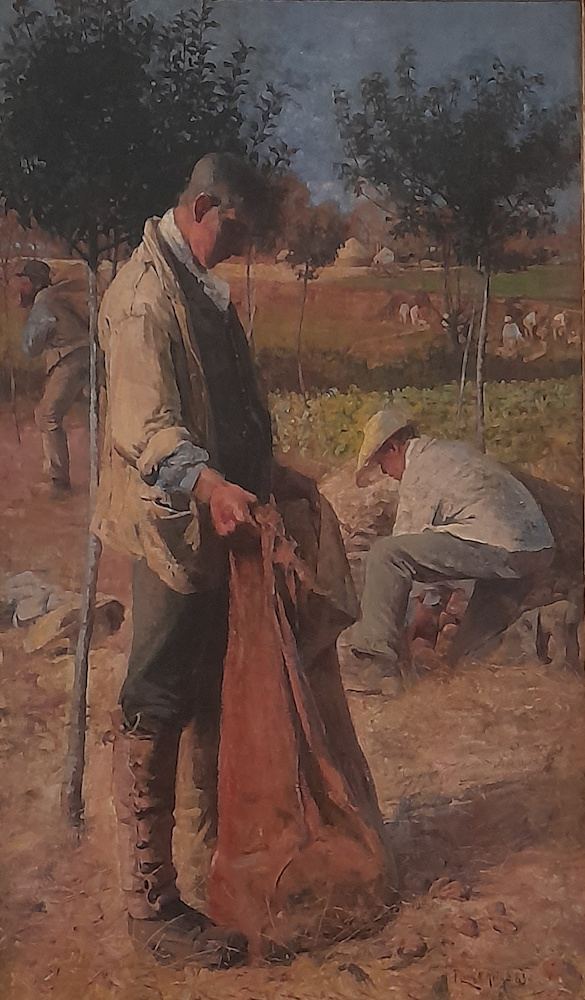

Left to right: (a) Flora Macdonald Reid's Fieldworkers, 1883. (b) Phoebe Anna Traquair's Portrait Miniature of Hilda Traquair, age five years, 1884. (c) Annie French's Two Ladies, c. 1895

The influence of French painting is often felt too, for example in Flora MacDonald Reid's Fieldworkers of 1883, a work that suggests the particular influence of Jules Bastien-le-Page. This is a truly absorbing painting, expressing the beauty of the everyday, even in the grind of daily labour. In dramatic contrast to this large work, as also to Melville's "blottesque" technique, is a delicately detailed miniaturist work on the opposite wall to Fieldworkers: Phoebe Anna Traquair's fresh and precise Portrait Miniature of Hilda Traquair, age five years (1884). The diminutive size of this is (ironically) one of the biggest surprises of the exhibition, and it comes rather unexpectedly in the fifth section, called "Swagger." Despite the prominence of the central figure, it seems far from the "grand manner" that the term denotes.

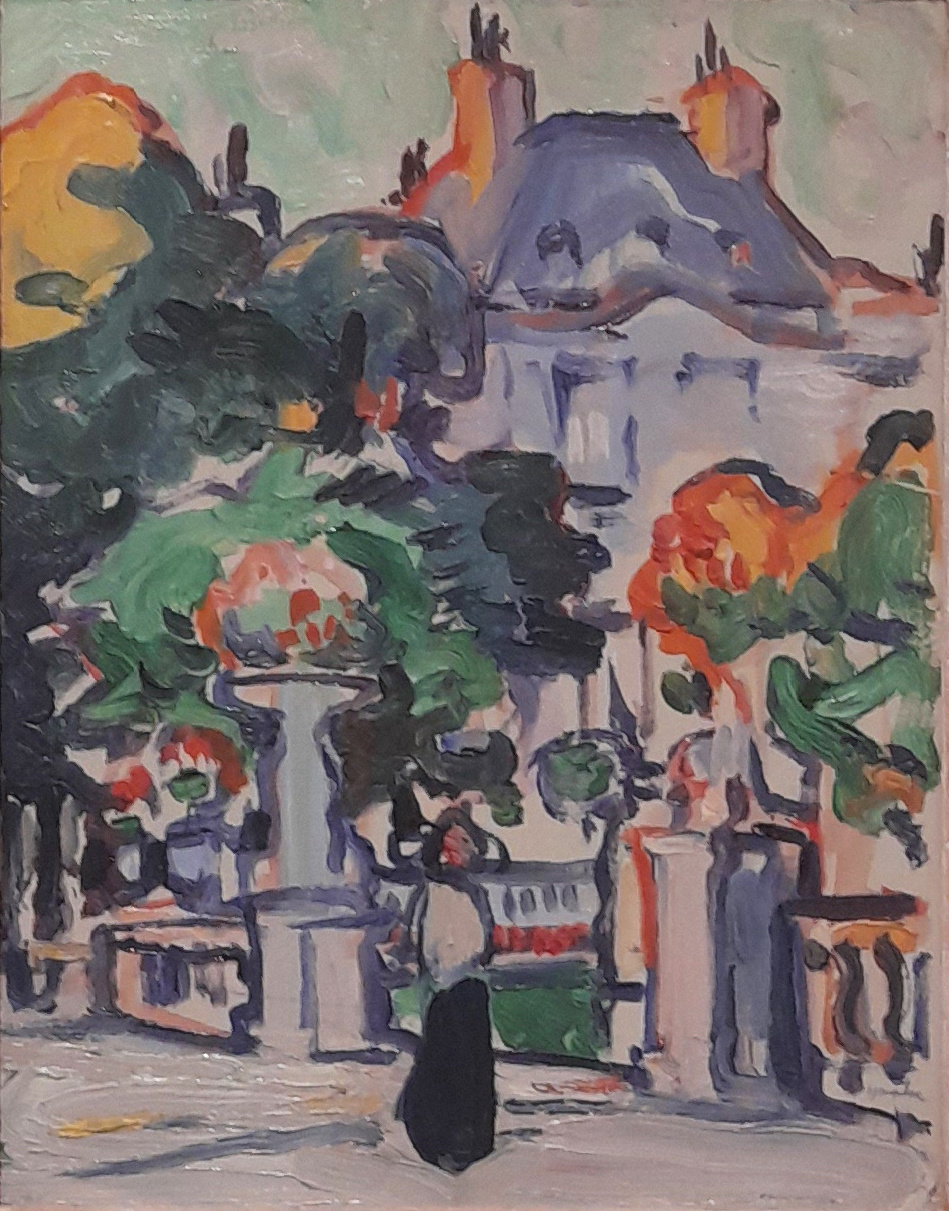

Left: Sir John Lavery's Blue Hungarians of 1888. Right: Samuel Peploe's Luxembourg Gardens of 1912.

Later sections also have much to offer: different influences (the Scottish Fauve artists, for instance, with S.J. Peploe's colourful Luxembourg Gardens, of about 1910); unexpected innovations (Iman Tajik used an inkjet printer to create his refugee image); the impact of war; and, as the works about refugees suggest, what it means to be Scottish in our own times. One section is given over entirely to the conceptual art of Ian Hamilton Finlay. Works in the Ingram Collection, continuing the story of Scottish art into our own times, are often more radically experimental. Yet, for all the sometimes startling developments on display here, there is a constant theme: the focus on Scotland. It is there even when other parts of the world are shown, or ideas from abroad incorporated. What appeals then is the difference, something brought out clearly in Lavery's The Blue Hungarians of 1888, in which crowds flocking to the International Exhibition in Glasgow have stopped to listen to a Hungarian band in their blue uniforms: the very title is arresting. The music has drawn people to these visitors from abroad, but only for the duration of their concert. This visiting exhibition in Woking's Lightbox successfully presents a people distinct in their vision, but open to new experiences; it gives the visitor a welcome entry into a rich, complex and ever-evolving culture.

Bibliography

Lightbox Final Fleming Object List (provided by The Lightbox, Woking, for reviewers of the exhibition there).

Created 25 June 2022