Juliet and her Nurse [Juliet and the Nurse], 1863. Oil on canvas, 43 x 50 inches (109 x 127 cm). Private collection. Click on images to enlarge them.

The subject of this picture is taken from Act III, Scene 2, of Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet. This scene is charged with high emotional tension with Juliet impatiently waiting for night to fall so that she can meet with Romeo to celebrate their marriage night. The arrival of her nurse, however, douses her anticipation because she bears the news of Tybalt’s death at the hands of Romeo, and his subsequent banishment from the city. In Stanhope’s picture Juliet is shown in despair because of the conflict between romantic love with familial duty. Juliet is depicted at twilight gazing out of the open casement window looking down at the red-roofed Verona, while the nurse sits nearby with a grave expression of both foreboding and love for her charge.

Cords of rope lie in on the floor that the nurse had procured at Romeo’s behest in order to aid his ascent to Juliet’s chambers to consummate the marriage. Trippi commenting on the complex psychological relationships between the characters portrayed notes: “Although Juliet’s hair is neatly braided, these ominous, uncoiling ropes and the ribbon fluttering on her sleeve indicate an emotional turmoil she cannot release in the nurse’s presence. Juliet’s passive gaze and gesture may hint not only at her anguish over Romeo’s misfortune but also at fantasies about the wedding night ahead.”

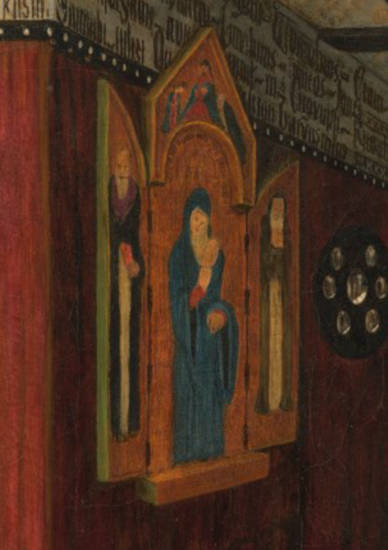

Details from the painting. Left: Juliet. Right: Triptych with the Virgin Mary. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The scene is rendered in rich and sumptuous colour allied with the careful representation of surfaces and textures that is characteristic of Stanhope’s early style. He has portrayed the interior space of the room and its contents with a meticulousness reflective of his study of Netherlandish Renaissance art that he would have been familiar with through the examples on display in the National Gallery. The meticulously rendered interior details are also reminiscent of Millais’s Mariana of 1851, another Shakespearian subject, but this time taken from Measure for Measure. Stanhope may well have seen Millais’s painting when it was shown at the Royal Academy in 1851.

Stanhope has depicted well a medieval interior with its half-timbered ceiling, latticed glass windows incorporating stained-glass crests, crimson wall hangings, and panels with Latin mottos stenciled in Gothic lettering running around the walls next to the ceiling. The ebony and ivory inlayed chair that the nurse sits upon was a prop borrowed from William Holman Hunt. Hunt later incorporated it into his Il Dolce far Niente of 1866.

The influence of Edward Burne-Jones can be seen in the arrangement of seven small mirrors set into a circular wooden frame, similar to those Burne-Jones had included in many of his depictions of early medieval interiors such as his Fair Rosamund and Queen Eleanor of 1861. The triptych of The Madonna and Child seen hanging on the wall in the background may have been loosely based either on a fourteenth-century altarpiece by Duccio in the collection of the National Gallery, London, or an altarpiece from the studio of Fra Angelico at Christ Church, Oxford. The depiction of the Madonna may be a symbolic portrayal of Juliet’s purity. The embroidery is not unlike those produced by Morris, Marshall Faulkner & Co., which had been established in 1861. This work was presumably painted at the studio of Stanhope’s home Sandroyd at Cobham in Surrey.

When this work was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1863 the critic of The Art Journal perceptively detected the influence of the well-known Belgian painter Baron Hendrik Leys: “’Juliet and the Nurse’ (624), by R. S. Stanhope, betraying medieval influences, probably reflected from the work of Leys, famous in the International Exhibition [of 1862, South Kensington]”(109). F. G. Stephens in The Athenaeum praised the picture, particularly its colours:

Mr. R. S. Stanhope’s picture, Juliet and the Nurse (624), deserves a much better place than it has. Notwithstanding slight evidences of inexperience in painting, and something of the like in composition, this work tells its tale with great spirit and success. It is carefully studied, without the ordinary stiffness of labour, and promises highly of the artist’s future. Mr. Stanhope has an excellent perception of colour, and a love of rich tone; the last would express itself better in his work than it does if he adopted a more solid manner than he now follows. [624]

Bibliography

“The Royal Academy.” The Art Journal New Series 2 (June 1, 1863): 105-16.

Stephens, Frederic George. “Fine Arts. Royal Academy.” The Athenaeum No. 1854 (May 9, 1863): 622-24.

Trippi, Peter B. “John Roddam Spencer-Stanhope. The Early Years of a Second Generation Pre-Raphaelite 1858-73.” M.A. Thesis. Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1993.

“The Royal Academy.” The Times (May 7, 1863): 7.

Last modified 7 May 2022