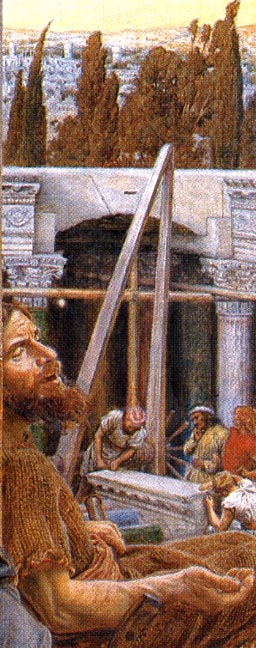

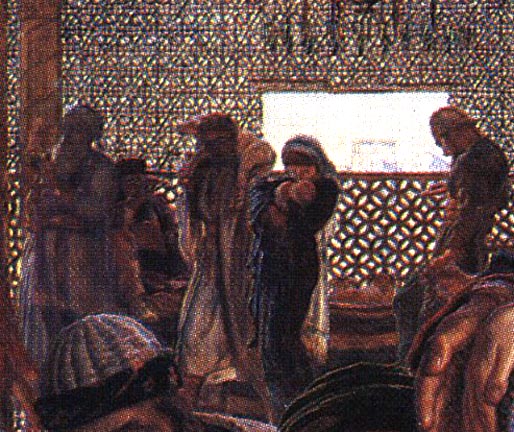

In The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, Hunt opposed inner and outer spaces while at the same time juxtaposing significant actions: in the courtyard of the Temple the builders are literally completing the edifice of the Old Law, while within its walls the young Christ performs the same function spiritually and figuratively. Futhermore, as F. G. Stephens pointed out, within the Temple itself Hunt divided the composition into "two groups; that of the Rabbis and their attendants, officers of the Temple, and that of the Holy Family. The first is arranged in a semi-circle, partly enclosing the second." We have already noticed that the painter chose this particular scriptural subject because it conveyed his deepest feelings about the way old and new encounter each other, and we should also observe that he devoted great care to rendering the nature of the conservative group in truly Hogarthian detail. Like Tennyson, Holman Hunt was concerned to emphasize that

The old order changeth, yielding place to new,

And god fulfils himself in many ways,

Lest one good custom should corrupt the world.

[Tennyson, "The Passing of Arthur"]

In his careful portrayal of the Rabbis who resisted Christ's message, Hunt chose to reveal the many ways in which the old faith had indeed corrupted itself and the world. Beginning with the chief Rabbi, he offers a series of psychological portraits which set forth the many ways and reasons that men have for resisting Christ — and all new truths as well. According to Stephens's helpful guide through Hunt's cast of characters, "Nearest of the Rabbis is seated an old priest, the chief, who, blind, imbecile, and decrepit," clutches the Torah to himself "strenuously yet feebly; his sight is gone, his hands seem palsied . . . He is the type of obstinate adherence to the old and effete doctrine and pertinacious refusal of the new." Thus, he not only is the representative symbol of those Pharisees who refused to believe in Christ — in the Messiah for whom they had been waiting — but he also prefigures all men who resist Christianity. "Blind, imbecile, he cares not to examine the bearer of glad tidings, but clings to the superseded dispensation," and his attitude is echoed by the second Rabbi, "a good-natured, worldly individual, with a feminine face, who, holding the phylactery-box, that contained the promises of the Jewish dispensation in one hand, touches with the other that of the blind man, as though to . . . express a mutual satisfaction in their sufficiency, whatever may come of this new thing Christ in conversation has suggested". Whereas the older man represents what the painter took to be an exhausted, feeble tradition and is himself psychologically incapable of entertaining any new ideas, this good-natured man will not allow himself to be troubled by any venturesome thought. He is a good member of the Establishment of any age and place, and although he chiefly explains the nature of those who opposed Christ in his own time, for Hunt he is also analogous to many an Anglican clergyman as well.

In his careful portrayal of the Rabbis who resisted Christ's message, Hunt chose to reveal the many ways in which the old faith had indeed corrupted itself and the world. Beginning with the chief Rabbi, he offers a series of psychological portraits which set forth the many ways and reasons that men have for resisting Christ — and all new truths as well. According to Stephens's helpful guide through Hunt's cast of characters, "Nearest of the Rabbis is seated an old priest, the chief, who, blind, imbecile, and decrepit," clutches the Torah to himself "strenuously yet feebly; his sight is gone, his hands seem palsied . . . He is the type of obstinate adherence to the old and effete doctrine and pertinacious refusal of the new." Thus, he not only is the representative symbol of those Pharisees who refused to believe in Christ — in the Messiah for whom they had been waiting — but he also prefigures all men who resist Christianity. "Blind, imbecile, he cares not to examine the bearer of glad tidings, but clings to the superseded dispensation," and his attitude is echoed by the second Rabbi, "a good-natured, worldly individual, with a feminine face, who, holding the phylactery-box, that contained the promises of the Jewish dispensation in one hand, touches with the other that of the blind man, as though to . . . express a mutual satisfaction in their sufficiency, whatever may come of this new thing Christ in conversation has suggested". Whereas the older man represents what the painter took to be an exhausted, feeble tradition and is himself psychologically incapable of entertaining any new ideas, this good-natured man will not allow himself to be troubled by any venturesome thought. He is a good member of the Establishment of any age and place, and although he chiefly explains the nature of those who opposed Christ in his own time, for Hunt he is also analogous to many an Anglican clergyman as well.

Their neighbor, a man "eager, unsatisfied, passionate, argumentative," represents a far different kind of person, for "his strong antagonism of mind will allow no such comfortable rest as the elders enjoy". He has been arguing with Christ when the entrance of Mary and Joseph interrupts the debate. In contrast, the fourth Rabbi, a haughty, self-centered man "assumes the judge, and would decide between the old and new. He is a Pharisee of the most stiff order. Beyond even the custom of the chief Rabbis and ordinary practice of his sect, he retains the unusually broad phylactery bound about his head." Between these last two figures appears one of the musicians, who "seems to mock the words of Christ upon some argument that has gone before, and, with one hand clenched and supine, protrudes a scornful finger, hugging himself in self-conceit. He is a levite, a time-serving, fawning fellow ... who would ingratiate himself with his seated superiors." The fifth Rabbi "has a bi-forked beard, like that of a goat, reaching to his waist," and this "good-natured, temporizing" fellow makes himself comfortable upon his divan "and would willingly let every one else be as much at ease". Again employing the principle of contrast, Hunt has made the sixth Rabbi "an envious, acrid individual, a lean man" who has arrived late at the Temple and stretches forward to see the face of the Virgin. The seventh and last of the Rabbis is a "mere human lump of dough . . . a huge sensual stomach [91/92] of a man, who squats upon his own broad base, and indolently lifts his hand in complacent surprise at the interruption". These seven men and their attendant musician provide a gallery of psychological as well as physical portraits of the Pharisees of Christ's time and of all ages. As Stephens explains, the painter leads us through "many forms of character, from the blindness of eye and heart of the eldest Rabbi, through the simple reposing confidence of the second, to the eager championship of the third, the self-centred complacency of the fourth, the indolent good-nature of the fifth," the envious hostility of the sixth, and the sensual complacency of the last. Both Hunt and Stephens were proud of Hunt's ability to record archeological and ethnographical fact, and Stephens devoted a great deal of space in his pamphlet to demonstrating the accuracy of Hunt's observations and hypothetical reconstructions of costumes, architecture, and physiognomy. But as he also emphasizes at length, Hunt was also concerned to create a gallery of psychological types, a gallery of varied humanity which would enable the spectator to experience this sacred event more fully, reliving it in his own imagination. Even as Hunt portrayed the details of costume and psychology of each participant, he made representative men, men who are types in a double sense: those who represent a particular kind of resistance to Christ's Gospel at the moment it appeared and who also represent — who prefigure — the resistance his message will meet throughout later ages.

To this encircling group of Rabbis, Hunt opposed the figure of Christ himself just as he is discovered by his parents. According to Stephens, he made a major contribution to sacred art by presenting Christ "as a man, and the Virgin as a mother; by no means as the spiritualized idealities of the early Italian painters, and still less . . . [as] the sensuously beautiful types of the later schools". Such an untraditional mode of representing the Holy Family, asserts Stephens, has the advantage of creating an art "far more catholic and [of] infinitely wider appeal" (Hunt and His Works, 61) than earlier painting. Hunt's version of the young Christ called forth powerful disapproval from some of the reviewers who did not accept that he could be depicted properly either as a Jew or as a member of the lower classes. Hunt himself would surely have numbered these critics among the spiritual descendants of those Rabbis who rejected Christ, and he would have done so in large part because they, like their spiritual ancestors, rejected precisely that which they supposedly awaited. Many of the critics continually complained about the lack of a truly English art, and here Hunt believed that he had been able to create precisely what they called for. Stephens, playing the part of Hunt's John the Baptist, several times elaborates upon this aspect of the painter's program, granting him high praises for "carrying out of a thoroughly English [92/93] principle; not alone in the minor fact that the mere execution is of the most workmanlike and complete kind, but because the idea of devotion to duty is inculcated by the very action of the chief figure," who is obedient to his earthly parent (Hunt and His Works, 61). Stephens likewise praises Hunt for creating a new version of the young Christ:

Divinely beautiful, he is yet humanly noble . . . We agree heartily with Mr. Hunt in not rendering this a simple type of passive holiness or asceticism, or merely intellectual power. A man, he is cast in the noblest mould; nobly beautiful, to express the glory of his origin and the greatness of his task — also strong and robust, to be able to do it . . . Mr. Hunt is as certainly right in the fine Englishness of his idea of the splendid body of our Lord (Hunt and His Works, 70).

although some reviewers harshly attacked Hunt's conception of the young Saviour and his parents, and his entire program of sacred realism, others agreed completely with Stephens. Once a Week announced that the Pre-Raphaelites could point to Hunt's picture as [93/94] the "absolute vindication of their principles," for, whereas hostile criticism had insisted that precise detail distracted, the Brotherhood had countered that "if all parts of the picture are truly painted, the interest of the human face will give it due dominance in the composition". According to Once a Week, The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple had proved the Pre-Raphaelite method workable, valid, and effective. The reviewer pointed out that Hunt's method challenged previous theories of religious art:

Great religious painters hitherto have striven to attain their aim through idealization — the countenance was idealized until it had almost lost its human interest — to mark the divineness of the subject the surrounding accessories were generally of a purely conventional character . . . by making the picture unearthly, it was sought to make it divine. With the Pre-Raphaelites the reverse; their principle is realization: in showing us as truly as possible the real, we are to behold the wonder of the divine. [101, quoted from the review of 14 July 1860]

This perceptive reviewer, who understood the artist's conception of sacred art, obviously believed it was valid: the sacred realism of The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple awakened rather than deadened [94/95] the spectator's imagination and sense of wonder. Hunt, he believed,had fulfilled his goal to create a religious art suited to the Victorian age.

Hunt's desire to convey both the visual and psychological "facts" of this historic event was central to his picture, but it provided only one half of his intention. He wanted to make his audience understand as well as see Christ's first encounter with the Law he had come to fulfil. Hunt's spiritual or symbolical intentions were clearly perceived by some of the reviewers, though, as usual, it is difficult to ascertain to what degree Hunt or his friends had primed them beforehand. At any rate, the Manchester Guardian was not alone in urging that

Mr. Hunt has something to say . . . His picture is replete with meaning, from the foreground to the remotest distance. Indeed, it absolutely overflows with significance. There are symbols everywhere, from the stray ear of corn, in the nearest of the foregro[u]nd, which indicates the feast of first-fruits, to the money-changer and the man who sells animals for the sacrifice, in the extreme distance. Nay, the symbols have overflowed the picture, and expanded themselves all over the frame. [24 April 1860]

[95/96] As this reviewer indicates. Hunt has employed a device — which he could have taken from sources as different as Hogarth, Early Netherlandish painting, and contemporary Bible illustrations — of a symbolic frame which prepares the spectator for the events unfolding within its bounds. On one side of the frame he has included the commonplace type of the brazen serpent, representing the "olden Law of Moses — of the sacrifice and substitution of an animal," while on the other he placed a "cross of thorns, with a garland of flowers about it, [which] expresses the New Law." Furthermore, the center of the frame "is surmounted by the sun at full glory, and the moon eclipsed" — which again opposes Old and New spiritual laws. At the foot of the frame appear heartseases, "the symbols of peace, and daisies, of humility, devotion, as well as universality"(Guardian, 78-79). Thus, the brazen serpent, which Hunt also used in his stained-glass design Melchizedek, represents the Old Law, and its opposing symbol of the cross of flower and thorn [96/97] indicates that we are seeing a confrontation of the two Las from which a new universal dispensation of peace, humility, and devotion will issue forth. We are to observe the rising of the sun, which will eclipse the doubtful, insufficient light of the Old Law with its brighter, life-giving beams. Hunt thus employs the frame, in the manner of Hogarth's inscriptions outside his design and of the texts appended to Bible illustrations, to make sure the spectator understands the nature of his subject; and, in the manner of Early Netherlandish painting, particularly the altarpieces he had seen in 1849, he uses the elaborate frame to emphasize the importance, the sacredness, of the events taking place within the picture: for his frame marks a clear boundary between the spectator's everyday world and the special, sacred world within.

The chief event which occurs within the bounds of this frame is Christ's self-revelation — which comes just after he has been disputing with the Rabbis and just as his parents discover him. In the gloss which Hunt inscribed upon the frame, we read:

The finding of the

Saviour in the Temple

and his mother said unto him, Son, why hast thou

thus dealt with us?

behold Thy father and I have sought thee

sorrowing.

And he said unto them, How is it that ye sought me?

wist ye not that I must be about my Father's

business?

As F. T. Palgrave pointed out, the picture which accompanies this text permits the spectator to observe "the turning-point from prophecy to fulfilment; the child's first consciousness of who he is, the earliest call to mission, the revelation of himself to himself." Hunt, as he was to do in The Triumph of the Innocents, shows Jesus encountering the world of spirit and eternity.

Moving from the frame to the picture itself, we note that Hunt has further pointed the way towards his meaning by placing a scriptural text on the circular gold plate on the temple wall immediately behind Joseph. Hunt's Key Plate to Holman Hunt's Picture of the 'Finding of the Saviour in the Temple' identifies the double inscription in Hebrew and Latin as Malachi 3:1: "And the Lord, whom ye seek, shall suddenly come to his Temple." The painter insisted that his artistic license in thus inscribing the text upon the wall of the Temple "demands but little indulgence, seeing that, without doubt, the whole of the Jewish world at that time were dwelling upon the hope of the Messenger coming to them during the existence of this particular Temple." Hunt again wishes us to perceive both Christ's encounter with the Rabbis and his own illumination. Hunt continues:

For the employment of the two languages, or rather of the Gentile one, which might be objected to, it is necessary to call attention to the fact that the inscription is upon a door which shuts the court of the Gentiles, and that it would therefore be desirable to have it in a language known to the strangers, as well as the Children of Israel. In proof that at this time it was necessary to consider this need, it may be adduced, that between the first and second cloisters of the Temple, there was a "partition, declaring the law of purity, some in Greek and some in Roman letters;" to which Titus alludes.

Left: Gustav Jäger. Joseph Interpreting Pharaoh's Dream. Right: Pieter Coecke. The Last Supper. Click on images for larger picture.

The use of typological and prophetical iconography within the furnishings of an interior is, of course, a commonplace device of the Flemish Masters and their descendants. Hunt would have known not only the standard iconography of the Flemish Annunciation but also the use of opposed types on the throne of the Van der Paele Madonna. The mirror surrounded by symbolic scenes in the Arnolfini Portrait closely approaches the idea of a symbolic disk, something which Hunt would have known from Pieter Coecke's Last Supper, and such symbolic disks — containing not types but prophecies — occur in Gustav Jager's Joseph Interpreting Pharaoh's Dream , which Hunt could have seen in the 1851 Art-Journal. Perhaps ironically for a Pre-Raphaelite, the ultimate source of this device was Raphael's Joseph Interprets the Dream of Pharaoh in the Vatican Logge. From so many approximations of his device of placing a prophetic text on a disk, it is difficult to determine Hunt's precise inspiration.

In depicting an event which he sees existing at the center of all human history. Hunt makes all the details of his painting reverberate so that they reinforce each other. To determine to what extent Hunt was understood by his contemporaries, it is worth quoting from the Once a Week review again:

When we turn from the group of the Holy Family, a unity of purpose binds together the separate details of the picture, and insensibly draws our thoughts back again to Him. The consecration of the first born; the lamb without blemish borne away for sacrifice; the table of the money-changer; the seller of doves; the blind cripple at the gate; the superstitious reverence for the Books of the Law, shown by a child who is reverently kissing the outer covering; the phylacteries on the brow; the musicians who have been assisting in the ceremonial of the Temple . . . little witting that the Boy before them is the descendant of the Royal Psalmist. So it comes to pass that this truthful rendering of detail strikes the chords of those feeling which vibrate in our heart with every incident of his sacred career. A grand prelude to the after ministry of Christ — conceived in a fine spirit - as the great musician places the theme of his leading ideas in the overture, which ideas are to be wrought to their fullness in the after portions of his work. [Quoted by Stephens, Hunt and His Works, 103]

All the details of The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple focus upon Christ and his mission, for they recapitulate all the older notions of [99/100] sacrifice, simultaneously indicating how they will be fulfilled in the Crucifixion.

Outside in the courtyard, as Stephens reminds us, we perceive "workmen

yet labouring to its completion, and finishing a stone which, when

raised, will be the 'head stone of the corner'" (Stephens, Hunt and His Works, 59-60). Many reviewers recognized this type as the one from Psalm 118 which Ruskin had employed

in his reading of Tintoretto's Annunciation; Hunt at last had employed

the specific typological image which had so excited him when he

encountered it in 1847. Stephens merely sets off the biblical phrase in

quotation marks, probably because he took it to be such a commonplace

text that it needed neither identification nor interpretation. Indeed, one

comes upon this type of Christ not only in Bible commentaries and

sermons but also in hymns by Isaac Watts and John Chandler and poems

by F. R. Havergall, 's Tractarian associate Williams, and

Tennyson's friend Trench. According to the immensely popular Bible commentaries of Thomas Scott, originally published around the turn of the century, the context of this passage

from the one hundred and eighteenth Psalm literally refers to

Outside in the courtyard, as Stephens reminds us, we perceive "workmen

yet labouring to its completion, and finishing a stone which, when

raised, will be the 'head stone of the corner'" (Stephens, Hunt and His Works, 59-60). Many reviewers recognized this type as the one from Psalm 118 which Ruskin had employed

in his reading of Tintoretto's Annunciation; Hunt at last had employed

the specific typological image which had so excited him when he

encountered it in 1847. Stephens merely sets off the biblical phrase in

quotation marks, probably because he took it to be such a commonplace

text that it needed neither identification nor interpretation. Indeed, one

comes upon this type of Christ not only in Bible commentaries and

sermons but also in hymns by Isaac Watts and John Chandler and poems

by F. R. Havergall, 's Tractarian associate Williams, and

Tennyson's friend Trench. According to the immensely popular Bible commentaries of Thomas Scott, originally published around the turn of the century, the context of this passage

from the one hundred and eighteenth Psalm literally refers to

David's advancement to the throne ... but the whole passage is evidently a prediction of Christ . . . The Redeemer doubtless is also that "stone which the builders rejected" and would have thrown aside as worthless among the rubbish; but which, by the mighty power of God, and to the astonishment of the apostles and disciples, became the Corner-stone, supporting the whole spiritual temple.

Scott's standard explication of this type therefore makes it quite clear, if we have not already grasped Hunt's point, that the completion of the Temple which we see materially carried forward in the courtyard is the precise physical image of the events occurring before us within the Temple: Christ, who has come to fulfil the Law and the prophets, is himself the cornerstone of the New Law. Furthermore, if we consider that Christ will have to be crucified according to the Old Law for the new dispensation to come about, it also becomes clear that the type makes a detailed parallel; for it is those working on the old Temple, the Jews, who will themselves place him as the cornerstone — by crucifying him — as the main element in the New Law. Scott's concluding remarks also suggest that Hunt's entire conception of the Rabbis owes much to typological interpretations of Psalm 118: "And as the chief priests, scribes, and Pharisees of old refused this Foundation-stone of the church; so many of the wise and learned, and professedly religious, of every age and nation ever since, have rejected it."In other words, the rejection of Christ's words by the Rabbis is an exact parallel of what is taking place in the courtyard of the Temple [100/101], just as it is a prefiguration of the manner in which some men will always reject Christ.

This familiar type has the additional significance for Hunt of combining type and prophecy. As Patrick Fairbairn's treatise on the typological interpretation of the Bible explains, "A type . . . necessarily possesses something of a prophetical nature, and differs in form rather than in nature from what is usually designated prophecy. The one images or prefigures, while the other foretells, coming realities." Hunt's concern in painting the instant that Christ realizes his mission (and perhaps his future as well) is to enforce upon the spectator that this is the moment at which Christ as Messiah enters human history. This is the point at which all types and prophecies converge. He therefore patterns his iconography according to a complex structure of types and prophecies which further serve, much in the manner of Van Eyck and Memlinc, to transform this realistically depicted earth and time into something more. Like his predecessors, he employs his iconography to generate a sacred space and time, transforming the earthly events represented into ones which also occur out of space and time. The effect cannot be precisely that of the Ghent altarpiece, because Hunt does not concern himself with a ritual, such as the mass, which takes place both on earth and eternally in heaven." What he attempts to do instead is make us see and feel the events taking place as if they were the focus of God's plan. We are meant to feel that here, with Christ's encounter with himself and the Old Law, divinity irrupts into time, changing it forever.

In his attempt to paint a work whose iconography can thus generate sacred space and time Hunt was at a disadvantage when compared to the Flemish Masters. In the first place, many of the greatest of the earlier works, such as the Portinari altarpiece and the Ghent altarpiece, depict an eternal mass, and this subject is not available to him, though it would have been to a member of the High Church. Secondly, Hunt's urge to create the unique, the novel, and the original prevented him from using older subjects in sacred art. It was not only that he found the body of saints irrelevant to his needs as believer and artist, but also that he felt little attraction to the Virgin as subject. Thus, he was not the least interested in older themes such as the Sacra Conversazione, and he had to find replacements for the older Annunciations, Crucifixions, Resurrections, Last Suppers, and the like.

Typological symbolism allowed him to do precisely that while yet permitting him to draw upon older themes and subjects. The symbolic potential of the type to place the spectator in the presence of two events, the prefiguring and its fulfilment, offered him a way of recasting the ancient subjects. Thus, The Scapegoat becomes his version [101/102] of the Passion and Crucifixion of Christ, while The Shadow of Death, which functions in terms of types within the Saviour's life, is also a foreshadowing of these events. One hesitates to extend this analogy with traditional subjects too far, yet within the context of Hunt's religious beliefs it appears that The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple stands as his version, much transformed, of the older annunciation theme. Since as a radical Protestant Hunt placed comparatively little importance upon Mary as other than a perfect human mother, he therefore has his annunciation come to Christ himself. Of course, God has already descended into human flesh, for Christ is already a youth standing before us, but it is at this moment in his life that the Holy Spirit descends upon him, revealing himself to himself. Appropriately, doves, the stock emblems of the Holy Spirit, have appeared within the Temple; and just as appropriately for the picture's second emphasis, which is the way men resist its appearance, someone tries to drive them out. Interested neither in the Catholic iconography of the Annunciation, nor in St. Birgitta's vision of it, Hunt does not include all the subsidiary iconographic details which refer to Mary's purity and the paradoxical nature of the incarnation. He does, however, include a wide range of symbolic details which function in a manner analogous to those in the Northern Renaissance Annunciations he had seen.

Some of these details of The Finding reinforce the significance of its central action. The blind beggar who sits on the Temple porch prefigures one of Christ's miracles — the restoration of sight to the blind which itself also serves as a type of his entire enterprise to enable man to see with new, higher vision. More important, perhaps, is the fact that the affliction of the beggar echoes that of the chief Rabbi, and by extension that of all the Pharisees within. As the Examiner recognized, "Blind Ignorance, sitting outside the Temple . . . is balanced . . . with a fine study of blind learning within."

The reviewer also pointed out that behind the group of Rabbis "in the airy distance of the Temple, a natural incident of the place foreshadows what shall come. A child is being carried up for consecration, and the lamb of sacrifice is taken from the ewe, who is restrained from following." This deployment of the levitical or legal type, one of the most familiar such images, widens our perspective, allowing us to see not only the law that Christ has come to fulfil but also the self-sacrifice which is to be the instrument of such fulfilment. Even here the painter has provided echoes, for just as the ewe has to be restrained as the lamb is taken from her, so Mary herself recognizes her new separation from her son. As Once a Week points out, Christ "stands isolated even in his mother's arms. Alone, as regards human sympathy, in this great era of his childhood." Even [102/103] the distant landscape serves to foreshadow Christ's final sacrifice, for as Palgrave observes: "Through the open door we see the first slopes of Olivet; we know we are near the earthly scene of the Death." This landscape, in turn, is echoed by the cross which Christ wears upon his belt, an ornament, as one critic remarked, that was "in common use from time immemorial, being the symbol of life even with the ancient Egyptians." Christ has come to give new meaning to that humble ornament, just as he has come unexpected and unwanted to give new meaning to the Law and to the Temple in which it is studied. Hunt has employed glosses, symbols on the frame, texts within the picture itself, the symbolic potential of Pre-Raphaelite composition, and a complex series of typological images and actions to create a painting that is truly "replete with meaning." [102/103]

Created December 2001 Last modified 27 October 2020