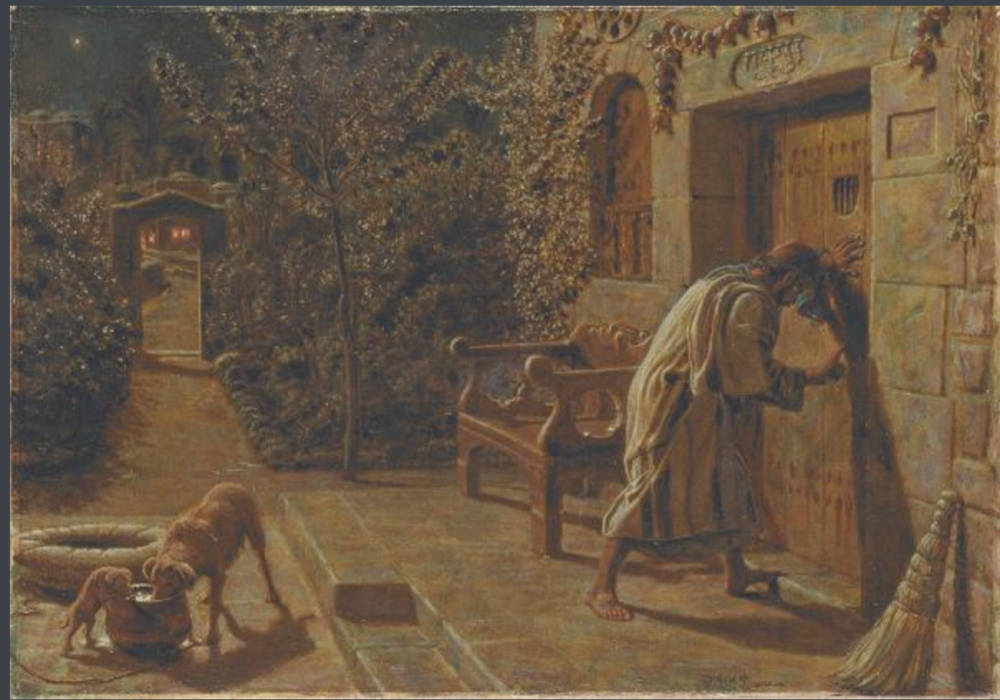

The Importunate Neighbour. 1895. Oil on canvas, 14 x 20 inches. Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria.

When Hunt wrote G. F. Watts during the summer of 1894, he had presumably largely completedThe Importunate Neighbour (1895), a photographic reproduction of which he had already included in Sir Edwin Arnold's The Light of the World or the Great Consummation (l893). This small oil painting, which measures 14 x 20 inches, was the last entirely new religious subject the artist painted, and it relates in interesting ways to his other works. Like Christ the Pilot, The Importunate Neighbour presents an image of man trying to return to his divine father and divine homeland, and so, despite the two pictures' very different subjects, they have more in common than one might expect. In fact, one wonders if the painter ever considered making The Importunate Neighbour part of the planned triptych. Given Hunt's own statement that The Light of the World and The Awakening Conscience were intended to form something very like a diptych, one perceives that he on occasion considered strikingly different subjects and images as cohering on thematic grounds.

This picture, one of several prompted by his fourth and last trip to the Middle East in 1893, illustrates Luke 11: 5-10:

And he [Jesus] said unto them, Which of you shall have a friend, and shall go unto him at midnight, and say unto him, Friend, lend me three loaves;

For a friend of mine in his journey is come to me, and I have nothing to set before him? And he from within shall answer and say, Trouble me not: the door is now shut, and my children are with me in bed; I cannot rise and give thee.

I say unto you, Though he will not rise and give him, because he is his friend, yet because of his importunity he will rise and give him as many as he needeth.

And I say unto you, Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you.

For every one that asketh receiveth; and he that seeketh findeth; and to him that knocketh it shall be opened.

John Everett Millais had illustrated this same text in The Parables of Our Lord (1864). Unlike Hunt, he chose to depict the friend handing the importunate neighbor the requested bread. If Hunt's figure of the pleading late-night visitor draws upon any of Millais's illustrations to The Parables of Our Lord, it follows "The Foolish Virgins" in representing a person standing against a closed door.

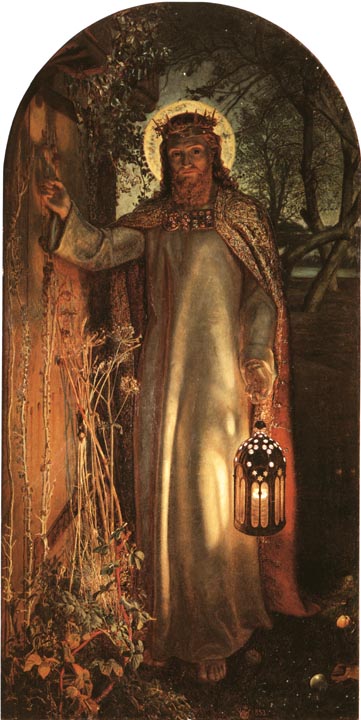

The Light of the World. William Holman Hunt. 1851-53.>Oil on canvas over panel. arched top, 49 ⅜ x 23 ½ inches. Keble College, Oxford.

The Importunate Neighbour, however, relates more obviously to Hunt's own The Light of the World since it provides an obvious companion image or complement to the artist's first great popular success. The Light of the World depicts Christ knocking on the door of the human heart, and it thus represents the way God in his grace awakens the human heart and conscience. The Importunate Neighbour, on the other hand, represents man seeking God — and God welcoming the seeker. For as Jesus tells his disciples: "Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you." Both paintings, then, create images of divine grace. In The Importunate Neighbour man is the active agent, the seeker; in The Light of the World Jesus is the seeker. Considered with respect to standard Evangelical paradigms of conversion experience, the two pictures represent subsequent stages of man's voyage to God, for whereas the earlier painting, which Hunt claimed recorded his own visionary conversion experience, depicts the first instant when man awakens to God, the second shows the awakened conscience, the convert, in search of his God and his salvation.

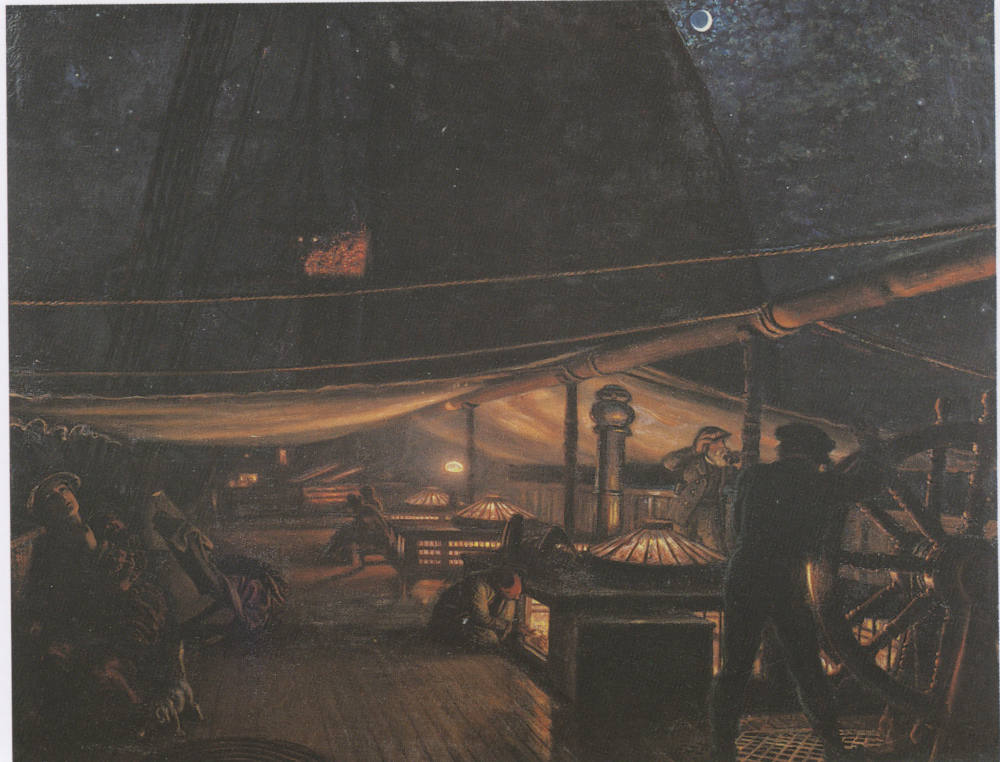

Although The Light of the World employs a vertical format and the later painting a horizontal one, both depict single male figures knocking at closed doors in settings in which vegetation plays an important part. Moreover, both are night scenes. Hunt had earlier painted London Bridge on the Night of the Marriage of the Prince and Princess of Wales (1863, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford), The Ship (1875, Tate Gallery), and the various versions of The Triumph of the Innocents (1876-1886, Liverpool, Tate Gallery, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University), and during his last trip to Italy, Greece, and the Middle East, he had painted several such night scenes, including the watercolors Athens (1892, Mrs. E. B. Tompkin) and The Nile Postman (1892, Lord Lambton). Certainly one reason Hunt chose a parable that had to be represented as a night scene was that, as he once wrote his friend the Rugby drawing master and minor sculptor, John L. Tupper, he always found such subjects far easier to execute than those set in the full light of day. In his letter of June 20, 1878, Hunt told his friend: "If 'The Light of the World' had required sunlight I should have had the difficulties of my task increased immensely" (Huntington Library M5). Since at this time he experienced difficulties with his vision that made working with color increasingly difficult, he would have had the additional reason of being drawn to a night picture — that he believed such works took less effort and caused less strain than a sunlight picture, and therefore he could preserve his failing sight for major large-scale projects, including the large version of The Light of the World and The Lady of Shalott (ca. 1886-1905, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford).

The Ship by W. Holman Hunt. 1875-79. Oil on canvas lined with blind stretcher), 75 x 96.5 cm. [Click on image to enlarge it.] Tate Britain. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported).

Nonetheless, we must conclude that Hunt's choice of a night scene that contains a single male figure knocking upon a closed door obviously owes a great deal to the fact that such a subject demands comparison to The Light of the World. At this time the artist had particular reason to concern himself with his first great popular success, which had been purchased by Thomas Combe of Oxford, his friend and financial advisor. As Hunt explained in a pamphlet written for the enlarged version's exhibition at the Fine Art Society, London, he had begun "the present replica of the original picture ... after an interval of half a century" because the public no longer had adequate access to it. On the day of Combe's funeral, his widow, who was deeply interested in the approaching opening of Keble College, determined to sacrifice this most treasured possession at once, and present it to the new foundation.

Hung in the Library at Keble College, it suffered (unnoticed) such serious damage, from the proximity of a hot flue, that, when, lent for the exhibition of 1886, with the general collection of the artist's work, it was found to be . . . virtually destroyed . . . Mr. Holman Hunt gave some weeks to re-painting the ruined parts, restoring it as far as possible to its original state. On its return to the College it was again hung in the library; in safety this time, but very disadvantageously as regards surroundings. In view of this, Mrs. Combe made provision in her will for the construction of a special chapel, in which the picture should find an appropriate home, and obtain careful and honourable treatment. It was evident that, presumably upon religious grounds, the picture was not regarded favourably by the authorities of Keble College; for when the chapel was built, the picture was at length placed there, but in a new frame, without the title, and bearing a different and totally inappropriate text.

The picture was refused for public exhibition at the Guildhall, London, and the permission for reproduction agreed to by the Warden was ultimately withdrawn by the Council. The artist, thus driven to the conclusion that his work was permanently hidden from the world, determined on the production of a replica. ["The Light of the World" by W. Holman Hunt now Exhibiting at the Fine Art Society's [sic], London, The Fine Art Society, n.d., 14-15. I would like to thank Mr. Peyton Skipwith of the Fine Art Society for his assistance in obtaining a copy of this catalogue]

Thus, during the period when the artist was bitterly disappointed both that he had not been invited to contribute to the decoration of St. Paul's Cathedral and that the Keble authorities had prevented the public from gaining adequate access to his most popular religious painting, he decided to make a larger version of it.ls The extent to which The Light of the World was then in Hunt's mind does much to explain why he should have echoed its composition and central ideas in a very different work.

In The Importunate Neighbour the artist characteristically recapitulates his earlier themes, subject, and pictorial techniques while yet trying to create a very different kind of work from what he had done before.16xx Whereas his major religious pictures all represent either scriptural history or reconstructions of incidents in the artist's personal, iconological, and formal concerns at this point in his career.

Shadows Cast by the Light of the World: William Holman Hunt's Religious Paintings, 1893-1905

[This article originally appeared in The Art Bulletin, 65 (1983), 471-84.]

- Introduction

- Christ the Pilot

- The Miracle of the Holy Fire in the Church of the Sepulchre at Jerusalem

- The Beloved

- Hunt's Themes of Conversion and Illumination Throughout His Career

Created 2001; last modified 3 August 2015