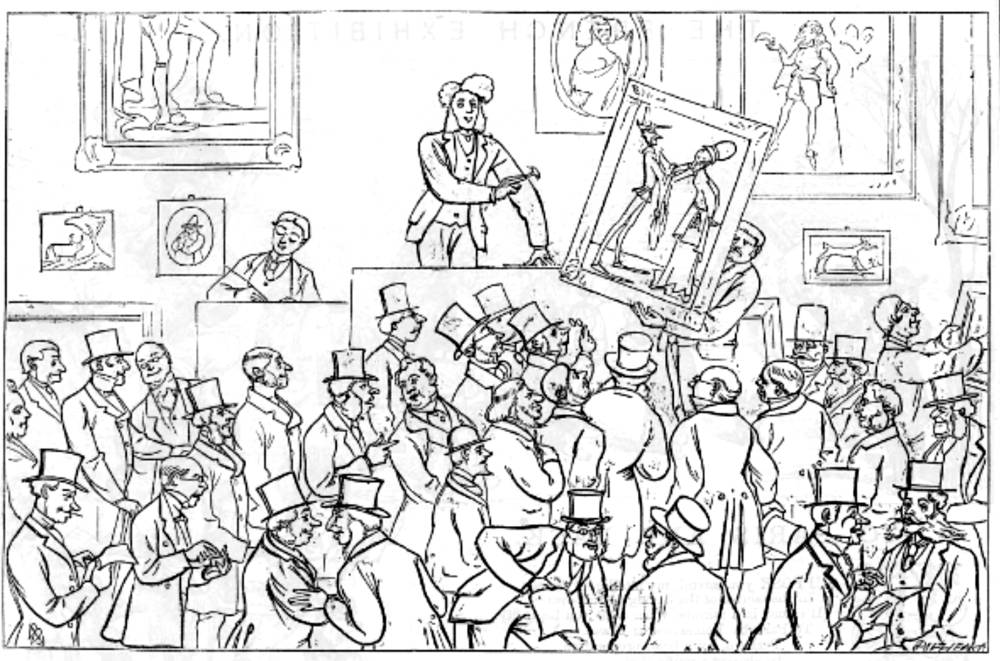

Reflections at a Picture-Auction. William S. Brunton (fl. 1859-71), artist. Fun (6 April 1867): 38. Signed with a monogram lower left. Engraved by the Dalziels. Courtesy of the Suzy Covey Comic Book Collection in the George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida. Click on image to enlarge it.

The author cites the “Medicis of Manchester,” the new men of money, because they were the earliest and largest collectors of the Pre-Raphaelites and other Victorian painters, and that fact explains why major works of both the Brotherhood and the later artists of the aesthetic movement are in Manchester, Liverpool, and other northern cities, and why other major works of these artists as well as Frederick Lord Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema came from the collections of the captains of industry. Of course, some these factory owners did speculate on art, but a good many left their collections to museums. John Ruskin’s defense of contemporary artists very much represents a movement away from the taste of many of the old aristocracy and was seen as such by conservative reviewers.

The accompanying text

It may shock those who are given to talking about “the increasing love of art” and the “munificent patronage of art by the Medicis of Manchester;” but there can be no doubt that Picture-Auction Rooms are only a species of Share Market, and that paintings are a kind of currency. As for the Manchester Medicis, in most cases it is to be feared they buy pictures as furniture. They see galleries of fine works in the houses of the old landed gentry, and they feel it necessary to have something of the same sort too. Pictures are an investment, and the only wonder is that so-called Art journals do not give the state of the market, just as the commercial journals record the rise and fall of shares. The Picture-Auctions would supply the needful statistics; and from them the list might be made out something in this style :—

“The demand for genuine Old Masters continues active. In Modern Works much business has been done, though, in consequence of the approaching Royal Academy sale, which begins on the 1st May, some large customers are holding back. Pickersgills are a little flat. Harts have a downward tendency. Creswicks are steady. There is an advance in Leaders, and Landseers go pretty briskly. Barneses show a tendency to rise. Millais's are lively, and there has been a call for Calderons. Sandyses command good sales, and in some quarters Burne Joneses are well looked after. It is stated there will be good business done in Armytages, Nicolses, and Petties next month.”

Nothing is more common than to meet with “patrons of Art,” who are coolly reckoning up the returns they are likely to get for their money.

“I say,” says old Cotton, the millionaire from Manchester, who has just dropped in at Dryer’s studio to see if there’s a bargain to be picked up in the way of Art, “I say, Dryer, how’s that chap Smalt getting on ? ”

“Oh, pretty well,” Dryer thinks; “seems to be always at work. Has been married lately.”

“How’s he getting on with his lectures,” Cotton means. “Do they sell well?”

“Yes, they sell very well,” Dryer is glad to say.

“I mean good prices,” says Cotton, careful to be particular in his interrogation.

“Yery good,” replies Dryer, who thinks it’s very kind of old Cotton to take such au interest in a young and struggling artist.”

“Glad of it,” says the Manchester man. “Fellow advised me to buy some things of his. Got ’em cheap—they’ll fetch twice what I gave for ’em now. Capital pictures!”

To a real lover of Art, a visit to a picture sale is full of interest. First of all there are the pictures to see—pictures he may never have the chance of seeing again; early works by recognised men, fetching good prices which they don’t merit. Early works by unrecognised men, fetching about half their real value. Then there are the buyers — men who buy pictures because they like them — men who buy pictures because they want to be supposed to like them — men who buy pictures because other people buy pictures — men who buy pictures as an investment. Next are the non-buyers — men who don’t buy pictures because they don’t care about them — men who don’t buy pictures because they can’t afford to buy them — men who don’t buy pictures because they can afford not to buy them. The varieties are endless. Some never praise or blame a picture till they have found out the painter's name in the cornor. Others always blame — others always praise. Then there are the people who know all the technical terms, and talk you stupid with keeping aud chiaroscuro, scumbling and glazing, and a host of more recondite words of obscure meaning.

For our part, we consider Picture-Auctions to be little bettor than slave marts. A man has no business to bo always buying and selling pictures, any more than ho has to be always changing a wife. He ought not to buy a painting until he is quite sure he really likes it; and once its owner, he ought not to be allowed to part from it unless he can show sufficient cause, such as poverty, for instance, before an Art-Divorce Court. It is a desecration of Art for a man to be perpetually changing the paintings on his walls, as if he were re-papering. The collections of such people should be confiscated, and added to the National Collection.

Related material

Last modified 5 June 2018