The Millais Collection is to be seen in the room adjoining the one where our friend, Pastelthwaite, exhibits his blotting-paper studies; and he has taken a leaf out of Punch's book to add to his own laurel crown, by framing our illustrated review of his artistic eccentricities. On this same page occurred a poem entitled “ Io Triumphe!” and and Mr. Whistler has pasted a sheet of tinted letter - paper over the poem, but left the “Io Triumphe!” as a note of jubilation. He might now change it from “Io Triumphe!” into “I pay triumphe!” as the sale of the Whistler’s effects—we mean the Pastels—has been marvellously remunerative; so that, on the whole, as compared with ourselves and the purchasers, he certainly has the best of the joke, — the best “by chalks.”

But let us pass from the “Jim” to the “Jem” Collection, i.e. that of J. E. Millais’ pictures. It is a perfect history of nis art, from Strawberries in March. 1851, to Ripe Cherries in December, 1880. A converted Pre-Raphaelite makes the best artist. Ask for a glass—there is no refreshment-room, but should Mr. J. Jopling be present, he will courteously provide you with the glass required, a very powerful one, a glass which clears out does not inebriate, and by its aid you can examine the marvels of the pre-Raphaelite painting as shown in Mr. Millais’ early works, when he used his brush on each particular hair of the human head with such care and attention as onlv a Truefit or a Douglas—who beards you in his own den in Bond Street—-could show, and gave the texture of cloth or tweed so faithfully that an experienced tailor could have priced the stuff for trousers at a glance.

No. 5.—Here he took a sacred subject, a touching tradition well known to the earliest Christian artists, and, preserving just so much of the old familar symbolism as would appeal to poetic sentiment, he brushed away halos like cobwebs, and gave us the muscular Christian’s view, in A.D. 1819, of a beautiful legendary episode of A.D. 10.

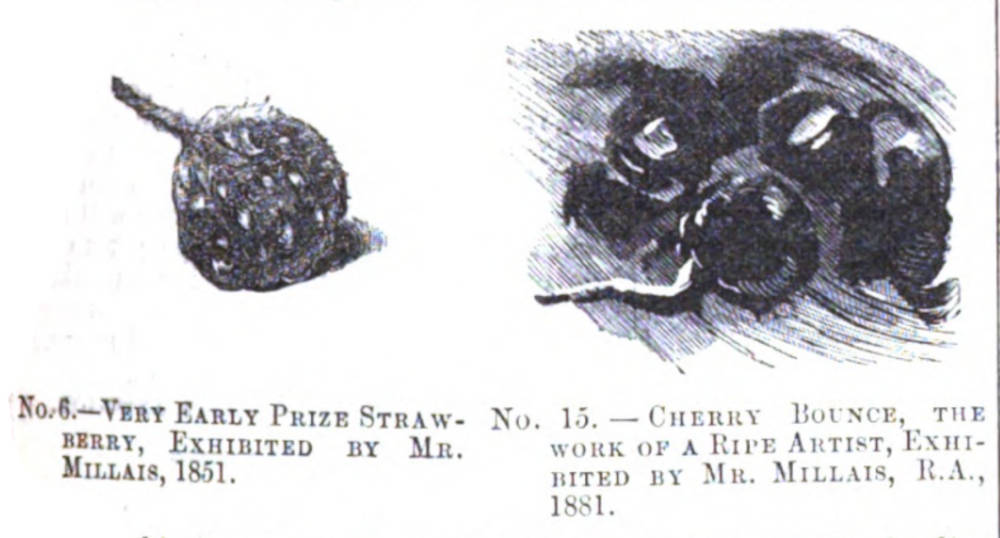

No. 6.—Mr. Millais made his Strawberry-mark in 1851, with “The Woodman's Daughter;" then, in a Pre-Raphaelite frenzy, 1855, exhibited his “ Autumn Leaves” 1856; and as a pre-Raphaelite convalescent, his “ Vale of Rest” 1859, which we may take as typical of the burial of tnat style of art as far as concerns Mr. Millais, who left it to the present resurrectionist school of Burne-Jones & Co., which only exhumed a corpse from which the spirit that gave it life has long since departed.

No. 15, “Cherry Ripe” is the popular picture, of course. Here we see how, in the Graphic Christmas Number, the poor young lady was cut off in her prune. Graphic proprietors might have written under their print, “to be continued in our next,” and given her legs in their Christmas Number for this year. If Mr. Millais adopted Mr. Whistler’s plan, he would exhibit our contrast of “Cherry “UNripe” just underneath. Poor thing! How different her expression would be if any of those twin cherries on one stalk— “Arcades ambo” i.e., blackhearts both—should not be quite as ripe as they look. Like the soldiers at Sir John Moore’s funeral, she would “ bitterly think of the morrow.”

No. 17.—Our old friend, “The Yeoman of the Guard” whose motto, to adapt a quotation from Professor Percival Leigh’s immortal Comic Latin Grammar, ought to be—

”Beefeater unus erat qui scarlet coatum habebat.”

That wonderful artist, Old Father Time, has vastly improved even this magnificent work of art. Time’s touches—ah well, they give even the greatest living artist a wrinkle now and then. Was it Time who took Mr. Whistler by the forelock and left his mark there?

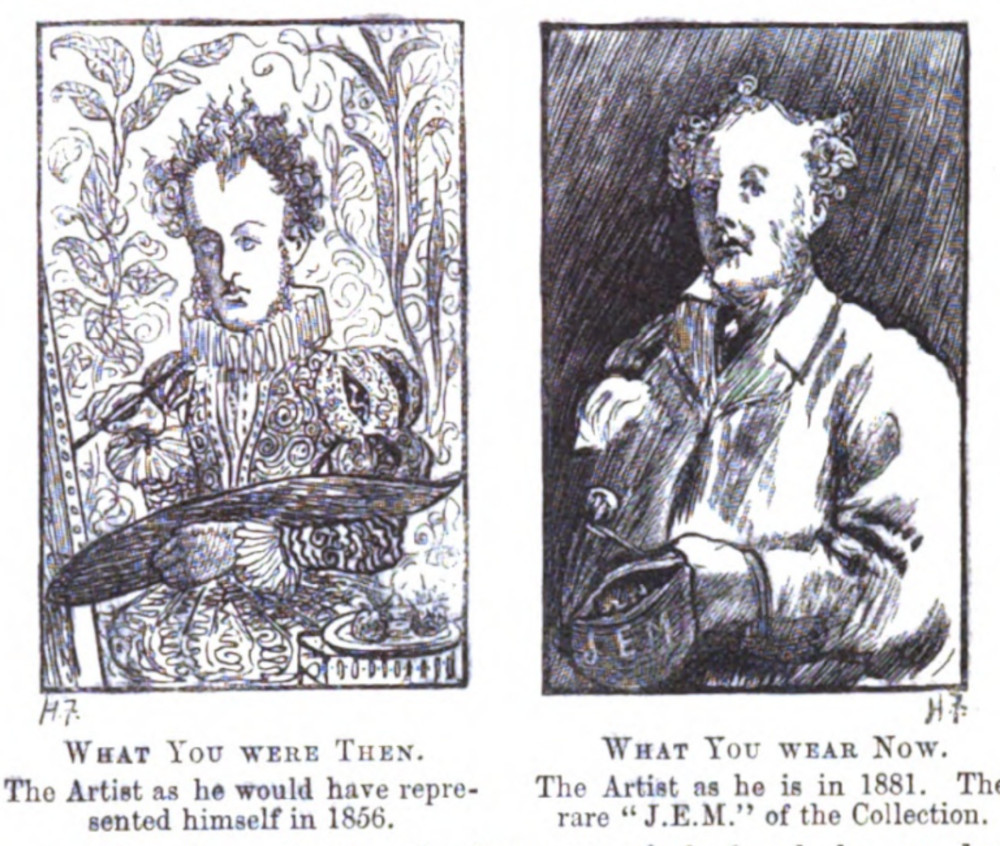

And here, Number Nothing in the catalogue, but Number A 1 in fact, is the portrait of the Great Artist by himself— as it should be. What wrould it have been had he painted himself in his pre-Raphaelite days! Every hair would have been— ahem!—well, at that time perhaps he was necessarily rather a master in Macassar oil, and tne treatment would not only have been very different but would have occupied a considerable time; while now, with a clearer head and a freer use of the brush, he can dash his own or anybody else’s wig off in a week, and we get a manly, sturdy, life-like portrait of a true artist, who learnt much as an “entered apprentice,” then Past Master of the Pre-Raphaelite Fraternity, and who is now rather Athletic than either ÆEsthetic or Ascetic, and in fact just what his portrait represents him—himself all by himself.

Links to Related materials

Created 2 May 2021