Painting

English Jews became active in the fine arts both painters and clients by the early nineteenth century. The mid- to late eighteenth century saw successful, well-to-do Jewish brokers and traders, such as Sampson Gideon and Abraham Goldsmid, emulating the wealthy English gentry with whom they consorted socially by having their portraits painted by leading portrait artists of the day – Robert Dighton, Benjamin Long, George Henry Harlow. Other Jews became artists themselves and achieved considerable success in a world quite new to those of their faith.

Two Eighteenth-Century Women Miniaturists

One of the earliest known Jewish artists was a woman, Catherine da Costa (1679-1756), a daughter of Dr. Fernando Mendes, who had been physician to Charles II and his spouse Catherine of Braganza, and the wife of Moses da Costa, a wealthy merchant and financier. After studying with the noted English miniaturist Bernard Lens III (1682-1740), da Costa created family miniatures of her father, her young son Abraham, and herself in the second and third decades of the eighteenth century and, in 1720, an imaginary portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots. Another Jewish woman miniaturist, Martha Isaacs (c. 1755-1840), the daughter of Levy Isaacs, an embroiderer, studied with the painter Thomas Burgess, before setting out for India to earn a living making miniatures of British subjects in Calcutta. She gave up working as an artist, however, after converting and marrying an agent of the East India Company in 1779

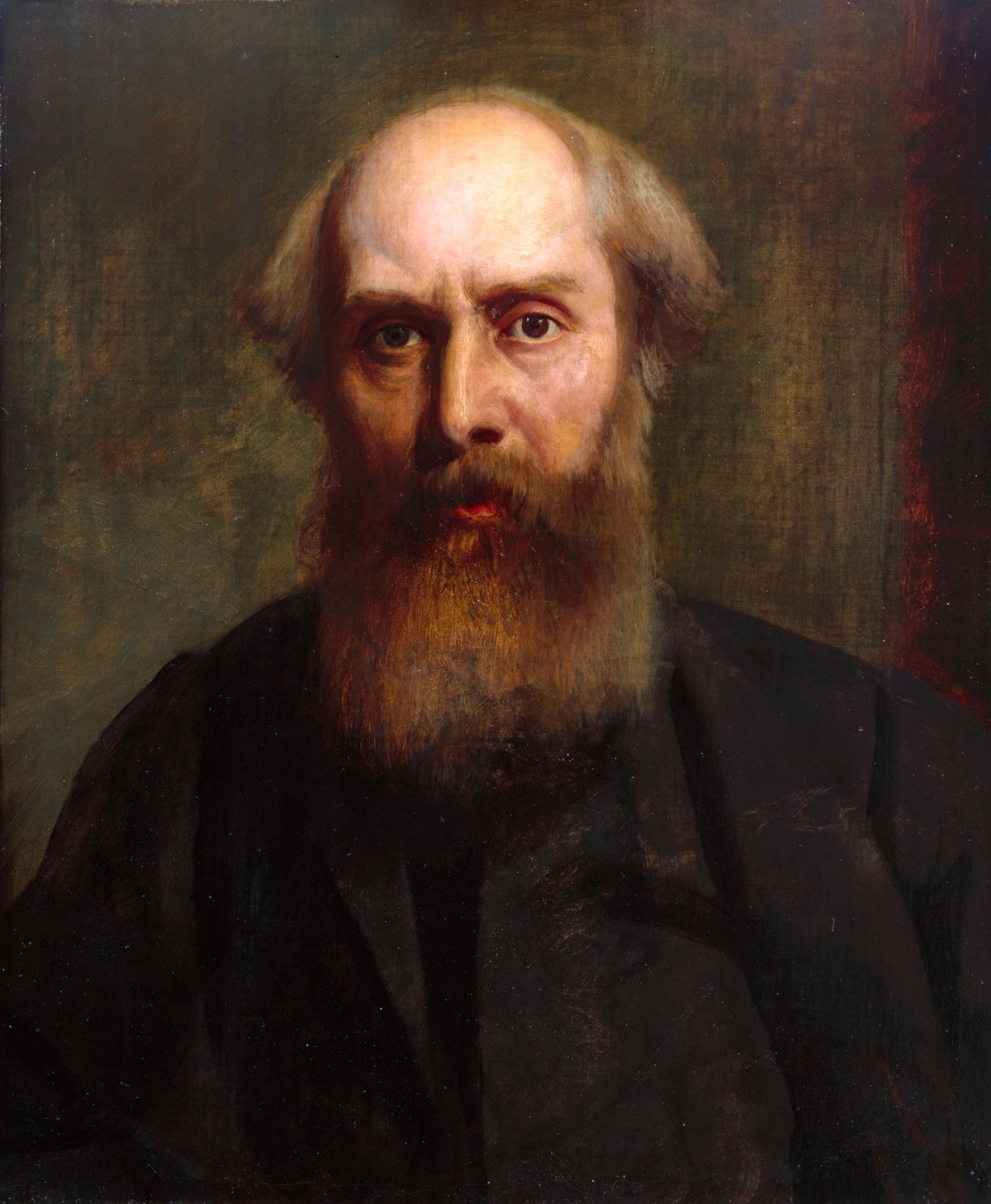

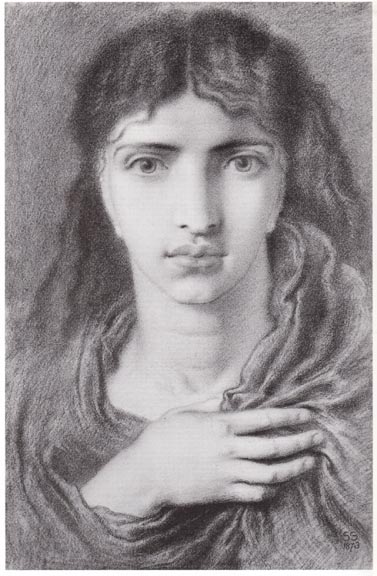

Solomon Alexander Hart

Two Self-Portrait by Solomon Alexander Hart as a young man (left) and when old c. 1860 — the first courtesy of the Prince of Wales Museum, Exeter, and the second, Royal Academy. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Far more productive, well remembered, still well respected, and fully in the mainstream of British nineteenth-century art, the painter Solomon Alexander Hart (1806-1881) became the first Jewish member of the Royal Academy and was on friendly terms with fellow-Academicians Sir Thomas Lawrence, J. W. M. Turner, and John Constable, among others. It was Hart, in fact, who introduced Turner to the Royal Academy Club of which at the time he was Secretary (Hart, 48-58.

Born in Plymouth to an engraver who had tried unsuccessfully to enter the school of the Royal Academy, Hart had a spotty education. “Being an Israelite,” he recounts in his Reminiscences, “I was debarred from entering Dr. Bidlake’s Grammar School” and “consequently was placed with . . . a Unitarian Minister” with whom “I remained the best part of five years.” There was frequent caning, the French lessons were given on the Jewish Sabbath and could not therefore be attended, and “my sums were done for me” by a fellow student. “Though living at a seaport,” he “was not an expert in swimming, nor in any of the other sports most youths are more or less proficient in.” As a result, he spent much of his time indoors “scribbling and drawing” (8-10). His father showed some of his work to engravers in London and he ended up as an apprentice at an engraver’s there, committed to “seven years’ service from seven in the morning until seven in the evening.” Hoping to escape this fate of “cruelty to animals,” he went to the British Museum in 1821 and made drawings from the Elgin marbles, with encouragement from the great Anglo-Swiss artist Henry Fuseli, then Keeper of the Museum (11). In August 1823 these won him admission as a student to the Royal Academy. “The necessity of earning my bread,” however, obliged him to accept commissions for colouring theatrical prints, making “copies of some Old Masters in miniature on ivory,” and painting miniature portraits of sitters, so that his days were taken up and he had time for study only in the evening.

Left: The Feast of the Rejoicing of the Law [Simchat Torah] at the Synagogue in Leghorn [Livorno], Italy. Courtesy of the Jewish Museum, New York. Right: Procession of the Law,. Vourtesy of the Jewish Museum, London.

His first exhibit at the Academy, a portrait of his father, left him dissatisfied, but in 1828, “to my surprise,” a small oil painting of “an Usher supervising the studies of some pupils” that he showed at the British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in Pall Mall was bought for £12 12s. (12). Two years later the first major painting of this Jewish artist– Interior of a Polish Synagogue at the Moment when the Manuscript of the Law is Elevated (now at Tate Britain) – was exhibited at the Society of British Artists and was purchased for £70 by Robert Vernon, a well-known collector of British art. This success led to Hart’s getting seventeen commissions for paintings of which, since each required six months to complete, he was able to produce only three – all three, by his own account, on religious themes: “English Roman Catholic Nobility taking Communion in the time of Queen Elizabeth” for Vernon, a Synagogue picture for a client in Belfast and A Lady taking the Veil for the Marquess of Lansdowne, the Whig politician (13).

Hart relates, however, that he “wished to avoid the imputation of being the painter merely of religious ceremonies” and was determined to demonstrate that he was capable of doing “something of a more definite character in the expression of human emotion and strong dramatic action.” To this end he produced a work illustrating the “quarrel scene” between Wolsey and Buckingham at the opening of Shakespeare’s Henry VIII. This was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1834, as was another history painting, Richard Coeur de Lion and Saladin, in the following year. Hart now became an associate of the Royal Academy (November, 1835) and in 1840 after exhibiting a massive fourteen feet square painting of The Execution of Lady Jane Gray, on which he later claimed to have spent an entire year, he was elected to full membership of the Academy, the first Jew to achieve this public recognition. In that same year, he was commissioned by the Duke of Sussex, the sixth son of King George III and Queen Charlotte and the uncle of the reigning Queen Victoria, to paint his portrait. The Duke, widely known as a Hebrew scholar and in general as well-disposed towards England’s Jewish community, sat for him in a large room in Kensington Palace (Hart, 124-26. Soon after, in 1842, Hart produced a large portrait (119.5 x 77.5 cm) of the young Queen Victoria herself, presently in the Ben Uri Gallery and Museum in London

An Early Reading of Shakespeare. 1848.

Courtesy of the Royal Academy.

From 1854-1863 Hart served as Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy, after which he became its Librarian. An observant Jew himself, he painted portraits of some prominent members of the Jewish community, such as Moses Montefiore (in 1869). At the same time, however, as the historian Richard Cohen points out, he addressed his work to the entire British art-loving community: “Though Hart left several paintings with Jewish themes, relating in particular to Jewish ritual, he expressed above all the inner desire of the Jewish artist who had broken ground and entered into a profession uncommon for Jews in the previous generation, to succeed in the general sphere. He did not want to be known as a Jewish artist engaging in merely particularistic themes relevant to only a select part of the society” (159). His work does indeed range widely, from portraiture, genre scenes, landscapes, and history painting to scenes from synagogue ceremony, from The West End of St. Alban’s Abbey in 1832, by way of The Young Falconer in 1835, span class="painting">The Young Queen Victoria” in 1842,

On the basis of a reference by Solomon Hart, Charles Towne (1781-1854) – usually referred to as “Charles Towne the Younger,” to distinguish him from a somewhat earlier painter (1763-1840) of the same name – has usually been considered a Jewish artist, though very little is known about him (Roth, Jewish Art, 534-35). Like his older namesake, he appears to have painted mostly animals (horses, cattle, hounds) and landscapes, usually with human and animal figures. The similarity of their work is so great that attribution to one or the other seems quite uncertain. One thing is certain, there is nothing “Jewish” about any of the works attributed to Charles Towne the Younger. They were clearly intended for a general, not a Jewish public.

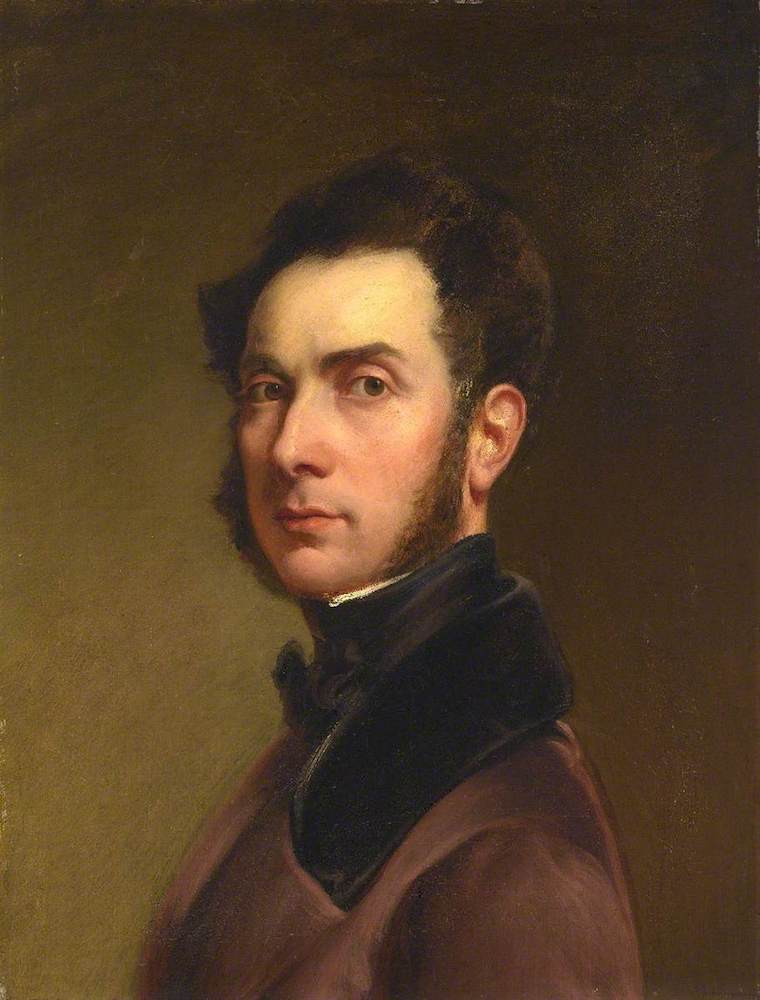

Abraham Solomon (1824-62)

ar better known and extremely successful as professional artists were the three siblings of the gifted Solomon family – Abraham (1824-62), Rebecca (1832-86), and Simeon (1840-1905). The son of one Meyer or Michael Solomon, an immigrant from Germany or Holland – who became a prosperous hat manufacturer, Freemason, and one of the first Jews to be admitted as a Freeman of the City of London, and his wife, Catherine Levy Solomon, an amateur painter of miniatures, Abraham Solomon entered Sass’s school of art in Bloomsbury at age thirteen, and in 1838 won a medal at the Royal Society of Arts for a drawing based on a statue. In 1839 he was admitted as a student to the Royal Academy, where in the same year he received a silver medal for drawing from the antique, and in 1843 another for drawing from life.

The prolific Abraham Solomon’s early paintings include portraits (My Grandmother [1840], The Duke of Wellington [1844], The Letter, Countess Eugénie, The Fair Amateur” [1860]), scenes from literary works in the Victorian anecdotal tradition (“The Vicar of Wakefield [1842]), and genre paintings in the same tradition (The Breakfast Table [1846], Too Truthful [1850]). In 1854, as one art historian put it recently, Abraham achieved a breakthrough in his artistic development which “not only gave him an enhanced reputation as an artist, but enabled him [. . .] through the medium of engravings and chromo-lithographs to become immensely popular on both sides of the Atlantic and lay the foundations of his considerable financial prosperity” (Daniels, 15; Lambourne, 274-86).

Three of Solomon Hart’s paintings that show the range of his subjects: Left: The Altar Boy. 1842, Courtesy of the Maas Gallery, London. Middle: The Flight from Lucknow. 1858. Courtesy of the Leicester Arts and Museums Service. Right: Mother and Daughter. 1854. Courtesy of the Maas Gallery. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The originals of the engravings and lithographs referred to in this comment were two paintings of railway carriage scenes, first exhibited at the National Gallery in 1854: First Class: The Meeting and Second Class: The Parting. Both demonstrated strong technique, while at the same time appealing to the sentimental strain in the Victorian social consciousness. Two similar works, both law court-related scenes, Waiting for the Verdict and Not Guilty or “The Acquittal” followed in 1857 and 1859.

Waiting for the Verdict< and Not Guilty. Both 1857 and courtesy Tate Britain.

All four paintings were well received by both art critics and the general public and engravings of them sold in large numbers. On the strength of these latest paintings, the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray urged the Royal Academy to elect Solomon to membership, which, however, it failed to do (Daniels, 16). In 1860, however, not long before his death, another work, Drowned! Drowned!, depicting the discovery of the body of a young woman who had committed suicide after being dishonored by a heartless man and appealing once again through popular engravings to the sentimental social consciousness of the broad Victorian public, was exhibited at the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition. This time around, Abraham was finally made an associate of the R.A.

Rebecca Solomon (1832-86)

fter receiving her earliest instruction in art from her older brother, Abraham’s sister Rebecca (1832-86), the youngest of three daughters in the Solomon family, took art lessons at the Spitalfields School of Design. Though – inevitably, as a woman artist – overshadowed in her lifetime by her artist brothers, she maintained a strong relationship with both, sharing studios with them at various London addresses from at least 1851 to 1862, the year of Abraham’s death, and thereafter with her younger brother Simeon from 1868 into at least the mid-1870s. Later in her career she became the caretaker of the errant Simeon. Contrary to what might have been expected of a woman from a traditional Jewish family at the time, she also socialised in her brothers’ wide and varied circle of gentile artistic, literary, and musical friends. Through at least the mid-1860s, for instance, George du Maurier and his wife Emma were regular guests at the elaborate receptions of the wealthy, art-, music-, and literature-loving Solomons and Rebecca in turn attended the du Mauriers’ dinner parties. Rebecca was also on friendly terms with Agnes MacDonald — later, as Mrs. Edward Poynter, the wife of a President of the Royal Academy and the aunt of Rudyard Kipling — and on at least one occasion “Aggie” stayed with “Beckie” and her family at 18 John Street, Bedford Row (Ferrari). In 1859 Rebecca joined a group of thirty-eight gentile women artists petitioning the Royal Academy of Arts to open its schools to women. This led to the admission of the first woman, Laura Herford (1831-1870), in 1860.

In 1850, work by Rebecca Solomon was exhibited at the British Institution; in 1851, at the Society of British Artists; and between 1852 and 1868 at the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy, her portrait of her brother (A. Solomon, Esq.) being included (Cat.# 1055) in the Academy’s 84th Exhibition in 1852 (Garish-Nunn, 19). Even after her death her work continued to be featured in the Academy’s annual exhibitions: “A Bit of old London” in the 135th Exhibition (1903, Cat.# 827), and The Fortune Teller) in the 142nd Exhibition (1910, Cat.# 1174). In later years Solomon went on to exhibit at the Dudley Gallery (opened in 1864), at Ernest Gambart’s French Gallery (opened in Pall Mall in the mid-1850s and rapidly established as the leading art dealer’s in London), at the Crystal Palace (in 1870), at the Society of Female Artists (in 1874) and at Birmingham, Liverpool, and Manchester. While copies of paintings by celebrated artists made up a good part of her earliest production – one of her best known works is a copy, begun when she was an assistant in the studio of John Everett Millais and completed by Millais himself, of the noted artist’s controversial Christ in the House of his Parents (several critics, including Dickens, objected to Millais’ “realism,” with one critic charging that the figure of Christ looked too much like a “Jew boy “) — she was soon producing paintings of her own, such as Evangeline) (1853, inspired by Longfellow’s 1847 epic poem of the same name), The Story of Balaclava) (1855) and Behind the Curtain) (1856). A couple of visits to France, probably chaperoning her already wayward brother Simeon, resulted in Lovemaking in the Pyrenees” and Spending a Sou” (both 1858.

Left: The Governness. 1851. Right: The Claim for Shelter [The Fugitive Royalists]. 1862, [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Many of Rebecca Solomon’s paintings reflect gender and social class differences in the England of her time. Among them The Governess) (1854), in which a sad governess looks longingly at the well-to-do, happily married parents of the child she is charged with taking care of, and A Young Teache) (1861) in which a child playfully instructs her mixed-race nanny. She also painted historical and literary themes, probably with the aim of winning recognition as a painter of serious subjects. The Fugitive Royalists) (1862; also referred to as The Claim for Shelter)), for instance, depicts a scene during the English Civil War in which an aristocrat and her son seek asylum from a Puritan mother and her sick daughter, while in The Arrest of the Deserter (1861, Israel Museum), based on a scene in an 1844 play Dominique the Deserter by William H. Murray, the main character, dressed in seventeenth-century clothing, is about to be led away in handcuffs, while a woman at his side pleads his case. By the mid-1860s Simeon’s friendship and close association with the Pre-Raphaelites proved influential on Rebecca. Her Woman on a Balcony (ca. 1865) follows the pattern of the Venetian portrait-style works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, and other Pre-Raphaelite associates, with a beautiful woman leaning out on a balcony gazing into the distance. The Wounded Dove) (1866) representing a young woman, her hair down, caring for an injured dove, and surrounded by Chinese ceramics and Japanese fans, reflects the newly popular Japonisme of the day.

At the height of her career, despite being a woman, Rebecca Solomon won recognition as a talented artist. Behind the Curtain (1858) was cited by a critic in Bentley’s Miscellany as “a first rate work.” Of Peg Woffington’s Visit to Triplet (1860), with its reference to Charles Reade’s recently published 1853 novel about the Irish actress, the Art Journal wrote, “This is really a picture of great power … gratifying, encouraging, and full of hope…. [Solomon] adds another name to the many who receive honour as great women of the age.” As many of Rebecca Solomon’s paintings were reproduced, like her brother Abraham’s, in the form of engravings, she was also, in her day, a popular and widely known artist.

In the last decade or so of her life, however, she fell from grace and never recovered the reputation she enjoyed in her best years. After the death of Abraham, the two younger Solomon siblings developed a closer relationship both personally and professionally. Trying to assist, restrain and reform her gifted but increasingly errant brother, she instead became herself associated with his notorious, morality-flouting ways and the bohemian company he kept. In 1873, at the height of a highly successful career as an artist, Simeon was arrested and charged with attempted “buggery” in a public urinal in England; though convicted, he managed to avoid imprisonment by paying a substantial fine, but not long afterwards, he was charged with “indecent touching” in a similar facility in France and spent three months in a French prison. Worn out by caring for her more and more roving, hard-drinking, overtly homosexual sibling, Rebecca, it is said, took to drinking heavily herself and produced less and less work of her own. Acculturation to gentile English society took an extreme form in this Anglo-Jewish woman artist.

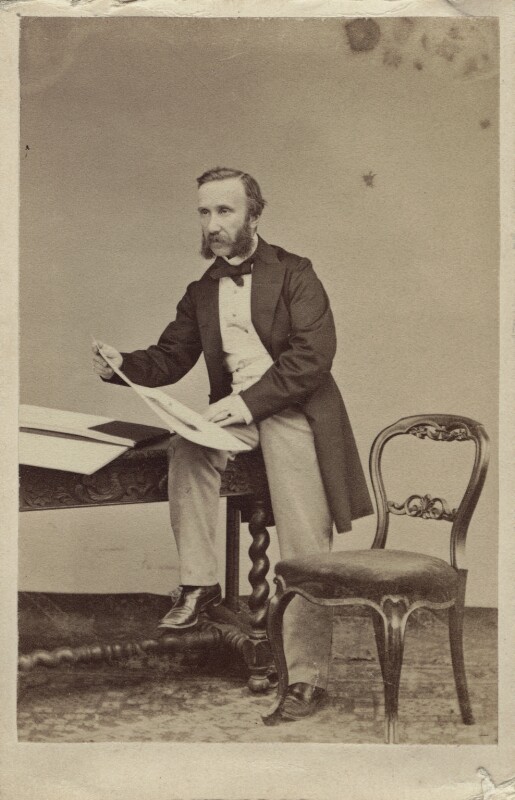

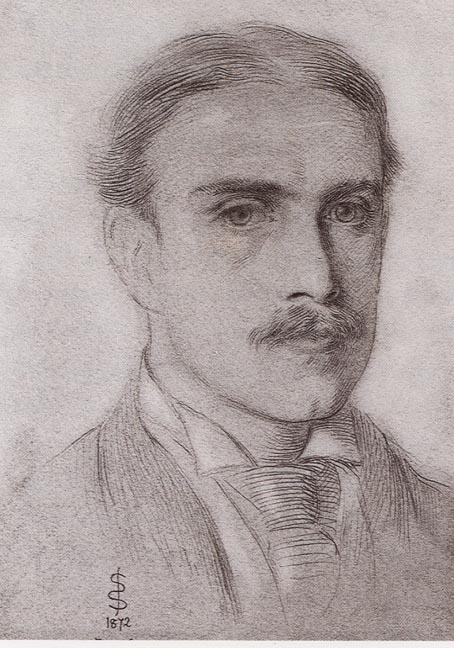

Simeon Solomon (1840-1905)

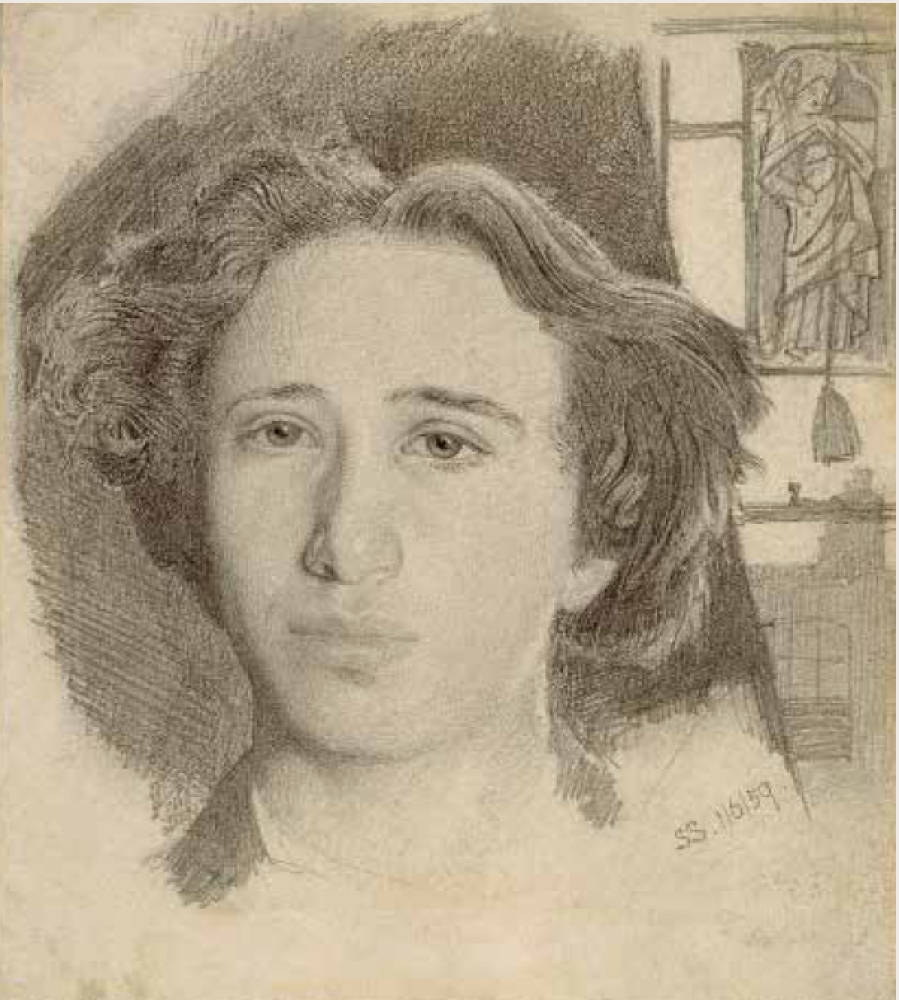

Self-Portrait, 1858. Courtesy of Tate Britain.

s Simeon Solomon was primarily active after 1858, when, with the admission of Lionel de Rothschild to Parliament, virtually full emancipation had been achieved, he will be the last instance of Jewish acculturation in the visual arts to be considered here – far more briefly than this gifted and troubled artist would otherwise merit. It was in fact in that very year, 1858, that Solomon exhibited his first Royal Academy work, a drawing entitled “Isaac Offered,” along with two further drawings at the Winter exhibition of the Ernest Gambart gallery. By the mid-1860s he had produced a considerable body of work and won the respect of both the public and his fellow-artists.

Though much influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, with whose members and immediate successors – Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Henry Holiday – he mixed socially, he also responded, especially in the earlier part of his career, to the urgings allegedly of his sister Rebecca by producing many paintings on Jewish themes (e.g. “Saul” [1859], “David Playing the Harp before Saul” [1859], “Babylon hath been a Golden Cup” [1859], “The Mother of Moses” [1860], “Shadrach, Meschach and Abednego” [1863]), as well as numerous engravings illustrating Jewish ritual (“Circumcision,” “Lighting of the Candles,” “Passover Seder,” ”Jewish Wedding”) in popular illustrated magazines, such as Once A Week and The Leisure Hour, as well as in the collection known as Dalziels’ Bible Gallery.

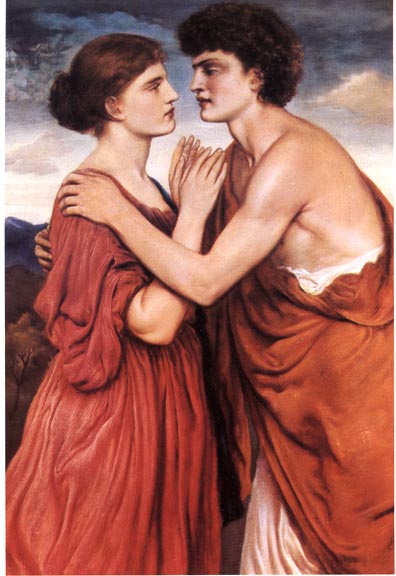

Three paintings showing the range of Solomon’s subjects — Classical Greek, Christian, and Jewish. Left: Damon and Aglae. 1866. Middle: Two Acolytes Censing, Pentecost. 1863. Right: The Mother of Moses. 1860. Courtesy of the Delaware Art Museum. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Even as an illustrator, however, he was not identifiable as different, because of his Jewish background, from other artists in the immediate succession of the Pre-Raphaelites. Many nominally Christian artists and friends – Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones, William Holman Hunt, Frederick Leighton, Frederick Augustus Sandys, George Frederick Watts – also contributed in the 1860s to the volume of illustrations of the Old Testament finally put out by George, Edward and John Dalziel in 1881. While always recognized as a Jew by his friends and fellow-artists, in other words, Simeon Solomon was not thought of as either a religious Jew (whatever his “religion” or “spirituality,” it was not identifiable with any established faith) or as a painter of primarily Jewish or Old Testament subjects. His work in fact ranged widely and he borrowed from Jewish, Christian, and Classical legend to express, through his images, his own longings and ideals, physical and spiritual. His art was understood and admired by the fellow-artists, poets, and critics who were his close friends and who were similarly inspired by the aestheticism of the time: Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Walter Pater, Algernon Swinburne, John Addington Symond.

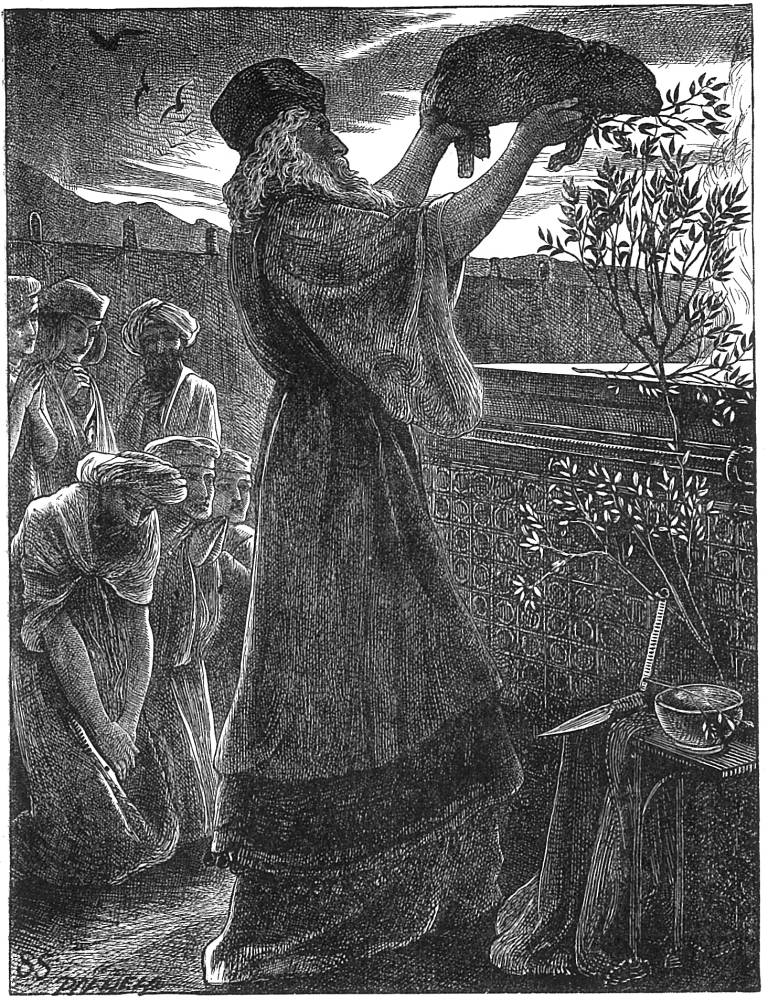

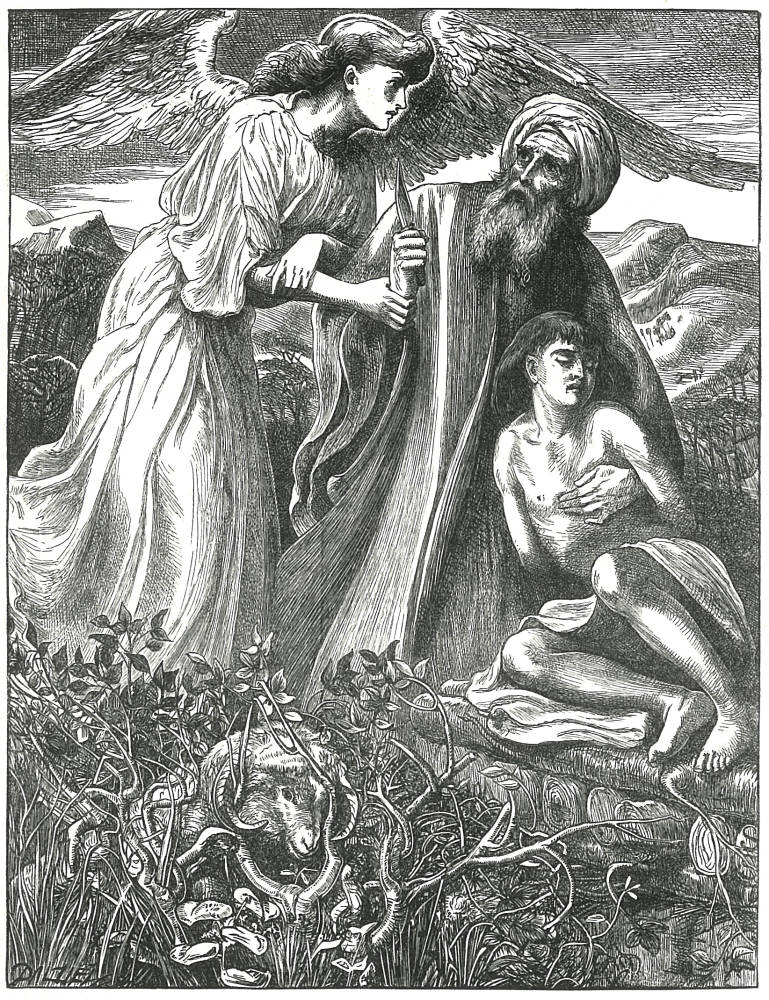

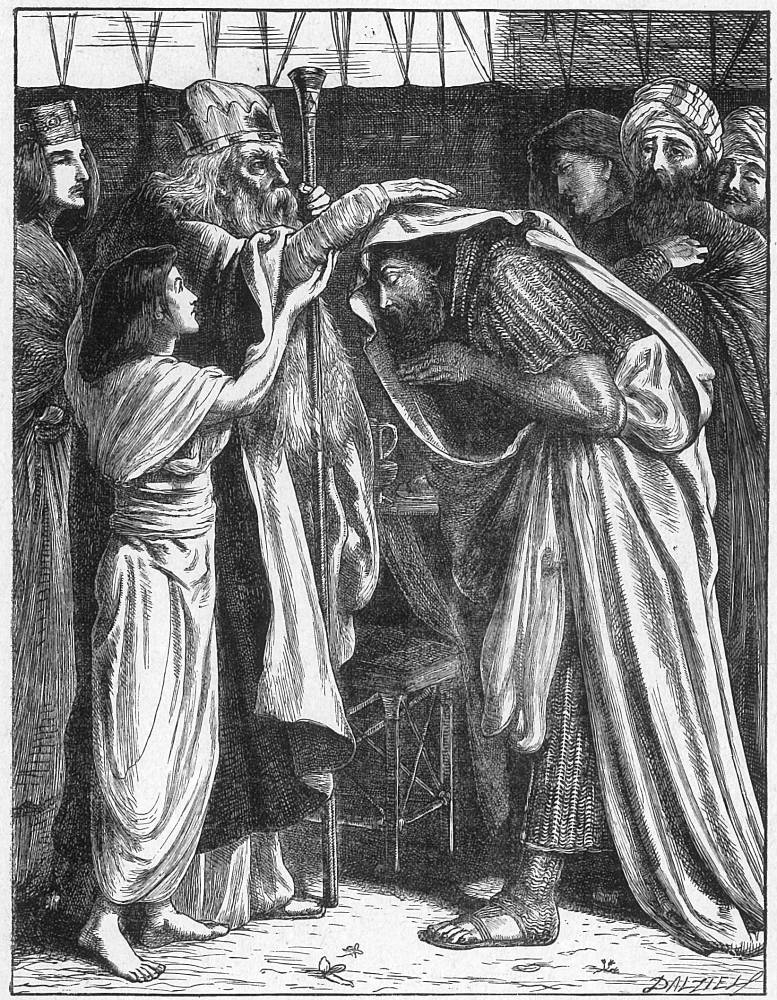

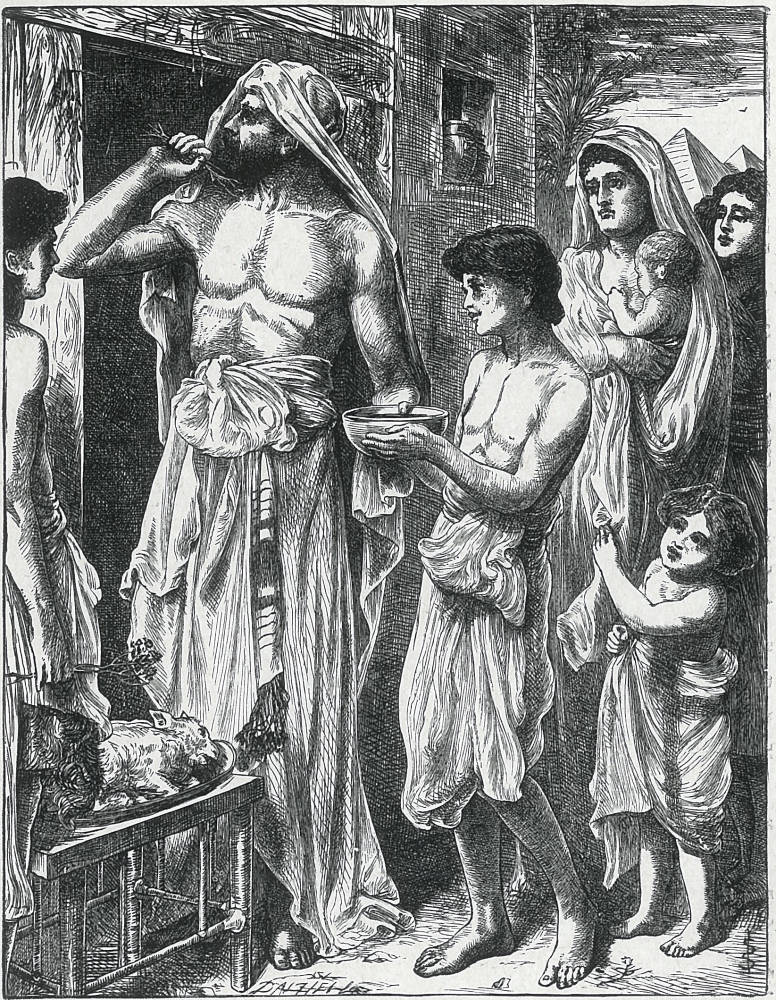

Four of Solomon’s illustrations of Old Testament scenes which are both Jewish and Christian, since each of the scenes depicts precisely those parts of the Old Testament Christian interpreters read as divinely intended types (or prefigurations) of Christ. Ruskin commissioned Rossetti to create Passover in the Holy Family, which the artist accompanied by a sonnet explaining the symbolism. Left: The Burnt Offering. Middle left: Abraham’s Sacrifice [The Sacrifice of Isaac]. Middle right: Melchisedek blesses Abram. Right: The Passover. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Almost from the start and increasingly as he matured, his human figures took on the androgynous character also found in the work of several other Pre-Raphaelite artists striving to transcend the restrictive, rigid, and in their view distorting and falsifying categories and oppositions of their time: spiritual and material, normal and perverse, masculine and feminine.

Left: Night. Middle: A Vision of Wounded Love. Courtesy of Peter Nahum. Right: Head of Hypnos, or Dawn. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The same-sex love that was one of the forms taken by Solomon’s searching for peace, beauty and transcendence of the everyday – portrayed sometimes directly or by suggestion, more often through figures that are indistinguishably male or female did not in fact alienate him from the Pre-Raphaelite artists, essayists, and fellow-poets who were his friends. On the contrary, some of them shared it in one form or another, and virtually none of them seems to have been in the least disturbed by it. There is even reason to surmise that Solomon and Swinburne may have had a homoerotic relationship of some kind.

Walter Pater. 1873. Courtesy of Peter Nahum.

The fact that virtually all his friends and associates withdrew from him and failed to assist him after he fell from grace in 1873 reflects not their own judgment of his sexuality, other than that he ought to have been more cautious and discreet, but their fear of being found guilty by association and of seeing the ill repute to which he was now subject, not only as a person but as an artist, extended to themselves. This was especially the case of Swinburne, who had indeed the most to fear. Among the consequences of Simeon’s fall from grace (an increasingly irregular life-style, homelessness, neglect of his person, and alcoholism), was the fact that he now had difficulty getting galleries to exhibit and sell his work. Symonds was unusually open on this score: “I wonder whether Hollyer [Frederick Hollyer, the well known photographer and engraver of Pre-Raphaelite art works –L.G.] would send me down for inspection any of Solomon’s drawings and pictures,” he wrote to his friend, the poet and essayist Horatio Forbes Brown, on 2 November, 1875. “I am interested by what you tell me, and I should be glad to help him. I never really liked his style as a man, so I do not feel any duty towards him as a previous acquaintance. But it touches me to the quick that a really great artist is in difficulties because no one will exhibit his pictures” (Symonds, letter 980, 2:388.

While Victorian English society on the whole was intolerant of any deviation from what was seen as normal love between men and women, there was some limited tolerance of same-sex love in the upper or cultured classes, provided discretion was carefully observed and the established social and moral order was not recklessly or directly challenged. It is doubtful, however, that there was a similar slackness in the Jewish community, in which male homosexuality had always been considered an abomination. Acculturation to gentile English society thus went further in the case of this noted Anglo-Jewish artist than in that of his sister Rebecca, who at least remained strictly faithful to traditional Jewish religious observances. His life after 1873 was spent in poverty and he died in a workhouse. His work in those later years, however, did not suffer the drastic decline often attributed to it. It continued to evolve and at times attained an originality missing from that of his heyda.

Bibliography

Cohen, Richard. Jewish Icons. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 199.

Daniels, Jeffery. “Abraham Solomon.” Solomon: A Family of Painters, exh. cat. London: Inner London Education Authority, 1985-8.

Ferrari, Roberto C. “Rebecca Solomon (1832-1886): A Brief Biography.” http:/www.simeonsolomon.com/Rebecca-solomon-biography.html (accessed 26.6.2020.

Garrish-Nunn, Pamela. “Rebecca Solomon.” Solomon: A Family of Painters, exh. cat. London: Inner London Education Authority, 1985-8.

Hart, Solomon Alexander. The Reminiscences of Solomon Alexander Hart, R.A. Ed. Alexander Brodie. London: Printed for private circulation by Wyman & Sons, 188.

Jaffares, Neil. “Isaacs, Martha, Mrs Alexander Higginson.” Dictionary of pastellists before 1800. Web. 22 July 2020.

Lambourne, Lionel. “Abraham Solomon, Painter of Fashion, and Simeon Solomon, Decadent Artist.” Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England, 21 (1962-1967): 274-8.

Mills, Rev. John. The British Jews. London: Houlston & Stoneman, 185.

Naylor, Aileen Elizabeth. “Simeon Solomon’s Work before 1873: Interpretation and Identity.” Birmingham University M. Phil. thesis, 200.

Ragussis, Michael. Figures of Conversion. “The Jewish Question” & English National Identity. New Haven: Yale University Press, 199.

Roth, Cecil. “Jewish Art and Artists before Emancipation.” Jewish Art: An Illustrated History, ed. Cecil Roth. New York: McGraw Hill, 196.

Last modified 22 July 2020