he area now known as Notting Hill was, before 1800, called Kensington Gravel Pits, a name which continued in use until the end of the nineteenth century. The hamlet was north of the village of Kensington and on the ancient main road from London to Oxford. Nearby was Kensington Palace, which had been enlarged by William III in 1689 to make it his main residence as he believed the clean air here was better for his health than the fogs of Westminster.

Part of T. Starling’s map of Kensington, 1822 (from Plate I in the Survey of London, Vol. 37, North Kensington).

The map on the right shows the gated turnpike road running along the top with a gravel pit on either side. Church Lane goes south to the village of Kensington and another lane known as The Mall runs parallel to this, backing onto the grounds of Kensington Palace. The Palace itself is bottom right.

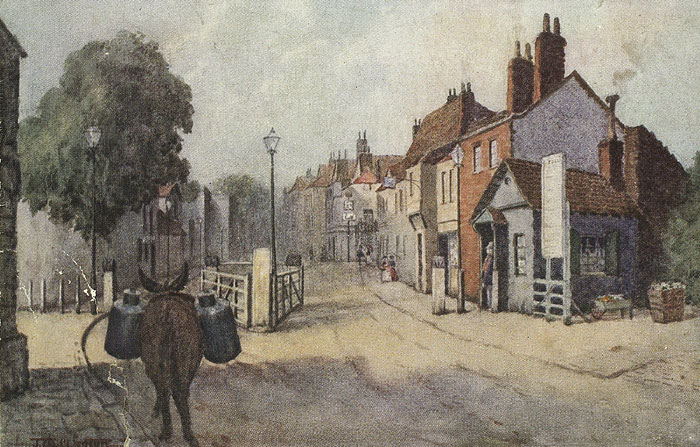

Individual Turnpike Trusts in England were set up across the country from 1769, with gates at intervals to halt the traffic and collect fees from the toll booth. At this particular junction the gravel was especially useful in maintaining the road in good condition as most of the land here was clay, ideal for making bricks but not for heavy traffic. The turnpike system remained in place for a century, with the gates here being removed in 1867.

The Notting Hill Toll Gate at the junction with Pembridge Road, by H. Oakes Jones - nineteenth century, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, by kind permission.

The first artist of any note to live at Kensington Gravel Pits was Augustus Wall Callcott (1779-1884) who was born here and lived at a house in The Mall all his life. An ancestor, Thomas Callcott, a bricklayer who had worked on the Orangery at Kensington Palace, had built several houses in The Mall in 1737. These continued to be occupied by his descendants, several of whom became distinguished musicians. Augustus Callcott was a chorister in his youth but showed artistic talent and entered the Royal Academy schools in 1797. He was a pupil of John Hoppner (1758-1810) and his first exhibited works were portraits. From around 1804 he turned to painting landscapes which formed his chief output for the rest of his career. He was elected RA in 1810 and his pictures became very popular, commanding high prices in his lifetime.

Portrait of Augustus Wall Collcott, RA (1779-1844), by John Linnell (1792-1882), 1847.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century the desire to escape from the increasingly polluted city prompted many Londoners to move to outlying villages. As Kensington Gravel Pits was already known for its clean air it became a favourite destination and In 1809 the artist William Mulready (1786-1863) was one who settled here. Born in Ireland, Mulready had come to England in 1800 to enter the Royal Academy Schools, aged 14, and studied for a time with the topographical watercolour artist, John Varley (1778-1842) who urged his pupils to go faithfully to Nature for their inspiration. In 1806 another artistic prodigy, John Linnell (1792-1882) came to study under Varley. Linnell had taken instruction from Benjamin West (1738-1820) but greatly admired the slightly older Mulready who he said offered him more artistic help and advice than any one else. The pair became good friends, lodging together for a time and painting portraits of each other and their tutor. They also made portraits of any acquaintances in exchange for a small sum. This was the best way to make money as landscapes, other than ideal classical scenes, did not have a ready market at this time.

Mulready was described by a contemporary, A.T. Story, as ‘a genial large hearted and handsome young fellow’. He had married Varley’s sister Elizabeth in 1803 when he was only seventeen, and began exhibiting at the RA in 1804. From 1809 to 1828 he gave his address as The Mall, Kensington Gravel Pits, where he was a close neighbour to Augustus Callcott and other distinguished members of the Wall and Callcott families. Later another relative, John Callcott Horsley (1817-1903) wrote nostalgically in his Recollections of a Royal Academician about his childhood at Kensington Gravel Pits, when the surroundings were still very rural and travellers on the roads risked attack by footpads. He also remarks on the many fine old elm trees in the area, regretting that the trees were cut down and most of the houses demolished during his lifetime. In spite of later rebuilding a few still survive, including Horsley’s own, 1 High Row, now numbered 128 Kensington Church Street.

Near the Mall, Kensington Gravel Pits, by William Mulready, c.1812.

John Linnell came to stay with his friend Mulready and both artists made studies of the country round them, including views of the gravel pits and brick kilns. Such industrial ‘low life’ subjects broke new ground but had little commercial appeal in an era that preferred the ideal landscapes of Claude Lorrain.

The Kensington Gravel Pits (located on the south side of todays Notting Hill Gate), by John Linnell, 1810-11 (click on the image for more information).

Linnell exhibited this picture at the British Institution in 1813. It did not sell for some time and Linnell eventually parted with it for £40, much less than he had hoped.

In 1814, after Napoleon’s dismissal to Elba, Tsar Alexander visited London to celebrate the victory with King George III. Edward Orme, who had a lease on the gravel pits, sold Alexander two shiploads of the best golden gravel to pave the forecourts of his Russian palaces. This may have marked the end of production here and the post Napoleonic building boom meant that the whole area was ripe for development, thus bringing in new profits for the landowners. A later group of street names, Moscow Road, St Petersburg Place and Orme Square, perpetuate the legacy of the once flourishing gravel pits.

William Mulready had four sons born in quick succession but his marriage was not happy and his wife eventually left him. J.C Horsley knew the Mulready family well and commented: 'Mulready was an affectionate and excellent father but after this painful break in the family circle the four high spirited, wild Irish boys were of necessity left much to themselves; and as they were all of the same pugnacious character a good deal of their time seems to have gone in fighting each other and the Kensington gamins'.

Left: The Fight Interrupted, by William Mulready, 1816. Right: John Sheepshanks and His Maid, by William Mulready, 1832-34.

David Wilkie had popularised genre painting - scenes of everyday life - and his friend Mulready, who had found only a small market for his landscapes, was now following this more lucrative path. The Fight Interrupted was his first major success and he was elected RA in the same year. His boys modelled for the main characters and were used by him in several other pictures. In 1820 Mulready had another success when his painting The Wolf and the Lamb was bought by George IV for the Royal Collection. But in John Sheepshanks and His Maid, Mulready shows another patron, the Leeds-born collector who had made his money in the cloth industry, in the drawing room of the New Bond Street house in which he then resided. Sheepshanks is surrounded by books and portfolios, while the housemaid brings in his letters and morning tea. His important collection of Netherlandish prints and drawings was sold to the British Museum in 1836, while his collection of 233 oil paintings (including both the works shown above) was given to the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1857. Mulready painted two portraits of him.

As well as these successful genre scenes Mulready supported his boys by teaching and painting theatrical scenery, so it was not long before he could afford to move to a larger house. He left The Mall in 1828 to live in Linden Grove (now Linden Gardens) one of the new developments on the north side of the turnpike road.

Links to Related Material

- Notting Hill Gate: A Nineteenth-Century Artists’ Enclave: Part II

- Campden Hill, Kensington: A Victorian Artists' Colony (in 6 parts with a bibliography)

Bibliography

Chavez, Lydia. Kensington Gravel Pits. London: Courtauld Institute of Art, 2016.

Gladstone, Florence M. Notting Hill in Bygone Days (rpt.), ed. Ashley Barker. United Kingdom: Anne Bingley, 1969.

Horsley, J. C. Recollections of a Royal Academician. London: John Murray, 1903. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California Library. Web. 10 March 2023.

'Plate 1: Part of Starling's map of Kensington (1822),' in Survey of London: Volume 37, Northern Kensington, ed. F H W Sheppard (London, 1973), p. 1. British History Online. Web. 10 March 2023.

Story, A. T. The Life of Linnell. London. nd. [full text]

Wood, Christopher, Christopher Newall and Margaret Richardson. Dictionary of Victorian Painters. 2 vols. London: Antique Collectors Club, 1995.

Created 10 March 2023