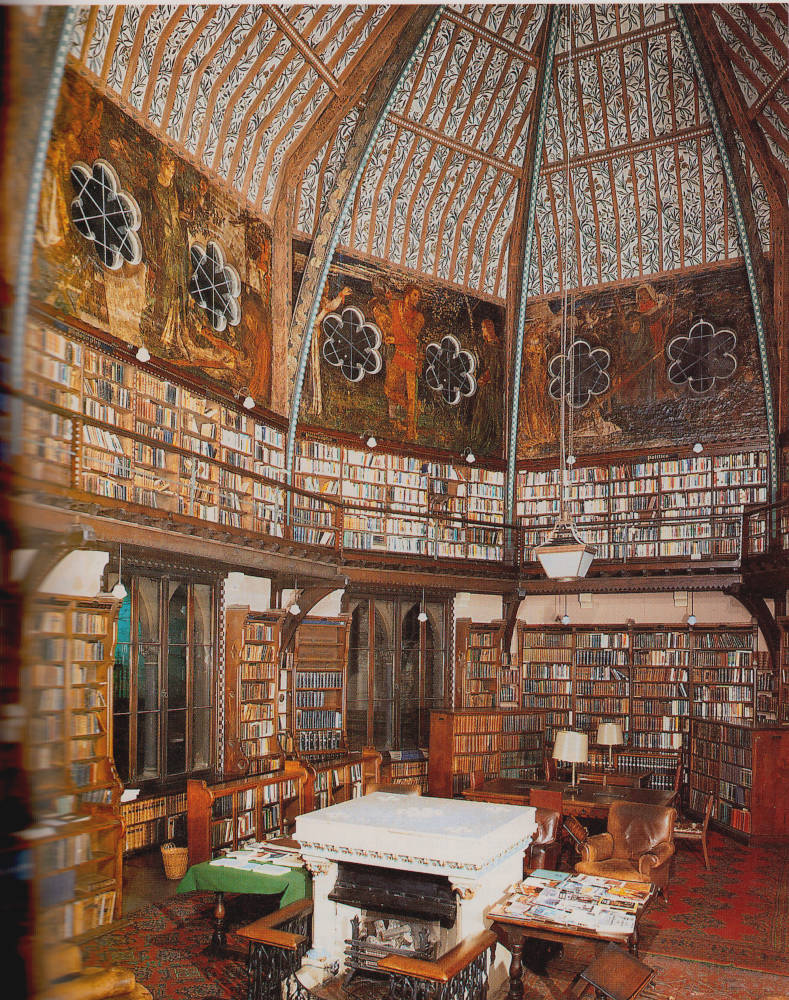

Left: The Oxford Union Library (formerly Oxford Union Debating Hall). Benjamin Woodward, architect. Right: Interior showing murals by D. G. Rossetti, Val Prinsep, and J. H. Pollen and the later roof decorations by W. Morris (1875). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The Oxford Union Debating Hall and the Second phase of Pre-Raphaelitism

The decoration of the Oxford Union Debating Hall, now the Oxford Union Library, was largely carried out between August to November of 1857 but not abandoned until early 1858. After March 1858 no further work was undertaken by any of the original seven artists. This project marks the beginning of the second phase of Pre-Raphaelitism. During the first phase of Pre-Raphaelitism, the period of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with its Ruskinian “hard-edge” style, the dominant figure in terms of influence on Victorian art had been John Everett Millais. In the second phase, however, the dominant influence shifts to Dante Gabriel Rossetti and then later to Edward Burne-Jones after Rossetti largely refused to exhibit his works publically. This project initiates the beginning of the medieval revival phase of Pre-Raphaelitism in both art and poetry. The seven artists who carried out this program of decoration, in effect, became a second Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. How this monumental project came about is an interesting story in itself.

View of the north-facing interior. J. R. S. Stanhope’s mural just to the left of centre.

Recruiting Artists for the Project

In the early part of the Long Vacation of 1857 Rossetti, accompanied by William Morris, travelled to Oxford to see his friend Benjamin Woodward who was the architect for the Oxford Union Debating Hall then in progress. The hall, a striking example of Victorian Gothic architecture, was a long building with apsidal ends. A narrow gallery fitted with bookshelves ran completely around the hall and above the bookshelves was a broad belt of wall divided into ten bays, pierced by twenty windows of a six-foil circular design, and surmounted by an open timber roof. According to Oswald Doughty “Rossetti had for some time dreamed of founding in England a great school of mural painting” (224). Rossetti therefore at once derived the notion of filling these ten bays with murals. Woodward eagerly embraced the plan to see his Victorian Gothic building embellished with medieval-inspired decorations. The Building Committee of the Oxford Union authorized the work on the condition that the paintings should be designed and carried out under Rossetti‘s superintendence. Rossetti decided the subjects should be based on Sir Thomas Malory’s fifteenth century Le Morte d’ Arthur. William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones had initiated Rossetti’s interest in Malory. In 1855, while an undergraduate at Oxford, Burne-Jones had discovered a copy of the Southey edition of Malory’s Morte d’Arthur in a local bookshop that he could not afford but which Morris bought straight away. The Victorians were already familiar with the Arthurian legends through the poetry of Alfred Tennyson but Malory offered a far grittier recounting of the stories as compared to Tennyson’s more conservative interpretations. Rossetti pronounced that Le Morte d’Arthur and the Bible were the greatest books in the world (Mackail 81). Christine Poulson felt that for Burne-Jones Le Morte d’ Arthur “filled the gap left by his abandonment of formal religion…because Malory offered in the Round Table and the Grail quest potent images of fellowship and idealism” (78).

The artists who were to be the executants were to offer their services for nothing but the Union would defray the expense of scaffolding and materials used, and the travelling and lodging expenses of the artists. Rossetti then set about finding collaborators. Ford Madox Brown, William Holman Hunt, and William Bell Scott were wary of the project and wisely declined an invitation to participate. Seven artists were ultimately involved in painting the murals. Not surprisingly Rossetti easily enlisted the help of his two younger disciples Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. He also persuaded his old friend Arthur Hughes and two of G. F. Watts’s students, Val Prinsep and John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, to enlist. Rossetti came to Little Holland House to use his powers of persuasion to convince the flattered but hesitant Prinsep to join. Georgiana Burne-Jones recounted Prinsep’s experience:

I had not studied with Watts without being well aware of my own deficiencies in drawing – so I told Rossetti that I did not feel strong enough to undertake such work. ‘Nonsense,’ answered Rossetti confidently, ‘there’s a man I know who has never painted anything – his name is Morris – he has undertaken one of the panels and he will do something very good you may depend – so you had better come! Rossetti was so friendly and confident that I consented and joined the band at Oxford. [159]

He arrived two days later to look at the project. Stanhope also reluctantly joined despite prophesizing failure for the project. When asked by Rossetti to join he wrote in a letter:

Rossetti has had the painting in fresco of the Oxford Museum entrusted to him. This is really a great mistake on the part of the managers, but I suspect it is the architect’s doing. He has a very ill-regulated disposition, as I believe that he has never completed a single thing that he has undertaken, and has only succeeded in finishing small things which he has managed to complete before he got tired of them; moreover he is quite unacquainted with fresco, and has never worked upon a large scale, so that I expect his attempt will prove a failure. Besides this he is decorating the Union Club there in distemper, - this is voluntary. He has asked me to go and do something there, as there are several fellows working, so I shall certainly go and see, and, if it is advisable to do so, I shall take my share in the work. [(]Stirling, 312-13]

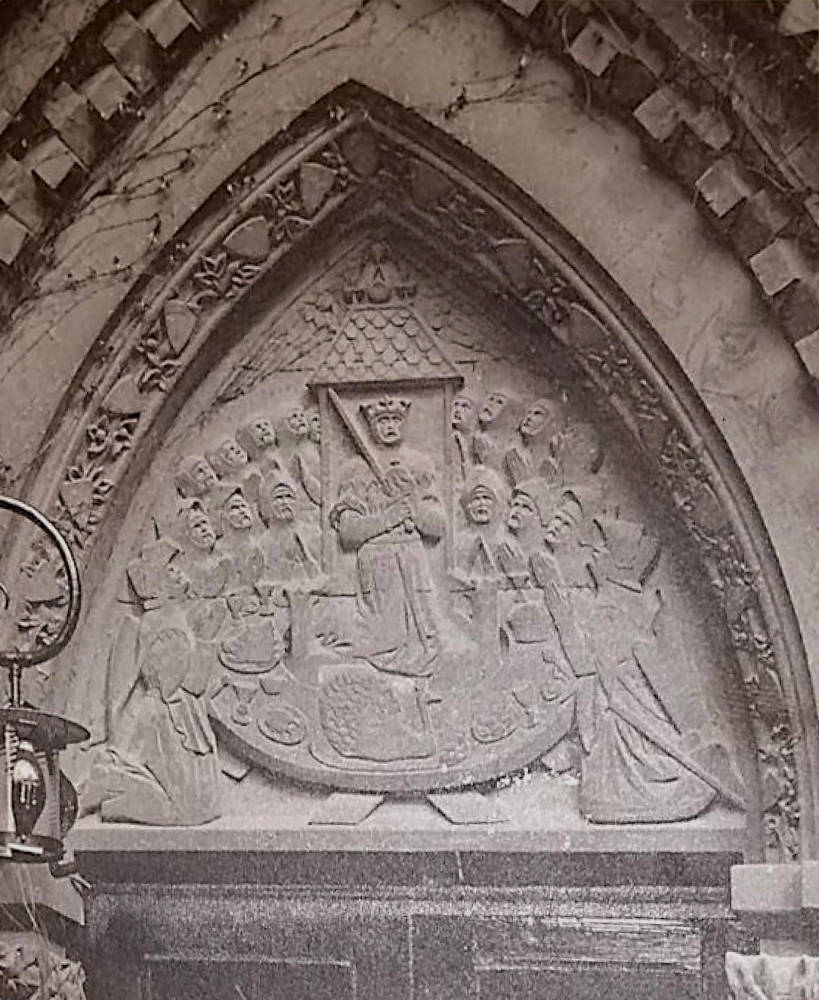

Perhaps the most surprising collaborator was John Hungerford Pollen, then aged thirty-seven, who Rossetti claimed, "was the only man who has yet done good mural painting in England" (Rossetti Correspondence, letter 57.29, 188). Pollen was then Professor of Fine Arts at the Catholic University in Dublin. In truth, however, none of these painters had any real practical knowledge of mural painting. Even Pollen, while he had decorated the ceiling of the Merton College Chapel in Oxford in 1850, had not executed real mural paintings per se. Rossetti had planned to decorate two of the bays, or if possible three, while the rest agreed to undertake one picture each. Eight, or possibly nine, of the ten bays were thus accounted for. In addition the sculptor Alexander Munro had agreed to carve a stone relief designed by Rossetti for the tympanum over the doorway to the entrance to the hall.

King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Alexander Munro. 1858[?]. Photograph courtesy of the Oxford Union Library.

Unfortunately because none of these artists had any practical knowledge of the art of fresco painting their project would be ultimately doomed to failure. One would have thought they might at least have consulted G. F. Watts for advice before starting since at that time he was engaged with the large fresco painting Justice: A Hemicycle of Law-Givers at Lincoln’s Inn, painted between 1853 and 1859. Mural painting necessitates a smooth, dry, and carefully prepared surface. The red brick walls of the Oxford Union building had been just recently built so the mortar was still damp and the bricks were not damp-proof. No ground whatever was laid over the brickwork, with the exception of thin coat of plaster and a coat of whitewash, so the artists didn’t take even elementary steps to better prepare the walls before they started on their task. The artists seemed to believe that paintings in tempera on an unprepared wall would last similar to traditional fresco paintings. Colour was laid on in tempera with a small brush similar to painting in watercolour on paper. The bays were some ten to twelve feet in breadth and at least nine feet tall, which required the figures to be painted larger than life size. Another problem in painting the murals was that each bay was pierced by two of the six-foil circular windows and this feature had to be incorporated into the design. This problem could best be resolved if the artist utilized a tripartite design, such as the ones adopted by Stanhope and Prinsep.

By early August Morris, Burne-Jones, and Rossetti were living together in lodgings at 87 High Street opposite Queen’s College and shortly afterwards the others arrived. By mid-August the project was well under way. Rossetti thought the project "a great lark" and it is generally been termed the "Jovial Campaign." Prinsep later recalled "What fun we had in that Union! What jokes! What roars of laughter!" (Burne-Jones, Memorials, 163). Although the artists appeared to have worked very hard on their murals, starting at 8 am and working as long as daylight lasted, Prinsep recalled that “the whole building rang with chaff and laughter…We worked hard, we younger men, and did our best. We were all wanting in experience. We had not method and but little knowledge” (169). In the evenings there was still time for practical jokes, friendly scuffles, smoking, playing whist, listening to their fellows recite poetry, and trying to avoid unwanted social invitations such as those offered by the well-intentioned, but boring distinguished scientist Dr. Henry Acland. There were also many discussions on art and literature. If models were needed the artists sat for each other. Burne-Jones, for instance, modelled for the head of Sir Launcelot in Rossetti’s mural. Later when the autumn university term began on October 16, and the undergraduate who owned their lodgings returned, Rossetti, Burne-Jones, and Morris moved from the High Street to new lodgings in a picturesque but squalid "crib" nearby at 17 George Street.

The subjects from Le Morte d’ Arthur chosen by the various artist

1. Dante Gabriel Rossetti - Sir Launcelot's Vision of the San Grael (Sir Launcelot prevented by his sin from entering the chapel of the San Grael)

2. Edward Burne-Jones – Merlin Lured to his Death by Nimue (Merlin Being Imprisoned Beneath a Stone by the Damsel of the Lake)

3. William Morris – Sir Palomydes’ Jealousy of Sir Tristam (How Sir Palomydes loved La Belle Iseult with exceeding great love out of measure, and how she loved not him again but rather Sir Tristam).

4. Arthur Hughes - The Death of King Arthur (King Arthur Carried to Avalon)

5. John Roddam Spencer Stanhope – Sir Gawaine Meeting Three Damsels (Sir Gawaine and the three Damsels at the Fountain in the Forest of Arroy)

6. Valentine Cameron Prinsep – The Love of Sir Pelleas for the Lady Ettarde (Nimue bringing Sir Pelleas to Ettarde, after their quarrel)

7. John Hungerford Pollen – The Finding of Excalibur (How King Arthur received his sword Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake)

8. Alexander Munro - King Arthur and the Knights at the Round Table, a sculptural relief.

William Morris’s mural Sir Palomydes’ Jealousy of Sir Tristam.

Morris’s mural of Sir Palomydes’ Jealousy of Sir Tristam was the first begun, the first finished, and generally considered the least successful of the group relative to his lack of artistic training. Pauline Trevelyan remarked in her letter to William Bell Scott of November 12, 1857. “You would be amused at Palamon [sic] in his garden of sunflowers - & the fair Iseult so hideously ugly that even the PRBs themselves can’t stand her“ (Surtees 278). Sir Palomydes was a Saracen knight who nursed a hopeless passion for Iseult. Morris’s mural features the rather crudely painted faces of the lovers Tristram and Iseult looking out in the upper right corner while the jealous Sir Palomydes watches them from the left. A twisting thicket of apples trees, and particularly sunflowers, from which the heads of the lovers emerged, covered much of the panel. The sunflowers were likely meant to symbolize a lost love. The theme of tragic unrequited love was one that was to have some reflection later in Morris’s own life. Some time after the completion of his mural Morris wrote to J. R. Thursfield, the chairman of the Oxford Union Fresco Committee, about the murals:

"As for my own, I believe it has some merits as to colour, but I must confess I should feel much more comfortable if it had disappeared from the walls, as I am very conscious of its being extremely ludicrous in many ways. In confidence to you I should say that the whole affair was begun and carried out in too piecemeal and unorganized a manner to be a real success – nevertheless it would surely be a pity to destroy some of the pictures, which are really remarkable, and at the worst can do no harm there. [Mackail 125]

After completing his mural Morris started work on decorating the roof “with a vast pattern-work of grotesque creatures” that incorporated quaint beasts and birds around foliage, the designs for which he made in a day. This became the first example of Morris’s innate genius for design. His collaborators noted it "was a wonder to us for its originality and fitness, for he had never before designed anything of the kind, nor, I suppose, seen any ancient work to guide him" (Burne-Jones 161). Morris worked all the autumn through upon the roof assisted by his and Burne-Jones’s old Oxford school friends Charles Faulkner and Cormell Price and by a friend of Rossetti’s named Swan. This was likely Henry Swan, a pupil of Ruskin’s at the Working Men’s College. The roof was completed by early November. Morris redecorated the roof in 1875 to a modified lighter and more sophisticated design utilizing the firm of decorative painters Frederick R. Leach to carry out the work.

Pollen’s mural of How King Arthur received his sword Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake follows Malory quite closely. King Arthur is seen punting himself towards Excalibur, which is brandished above the surface of the lake by the Damsel of the Lake who gives him the sword. The wizard Merlin stands behind Arthur in the boat. Pollen whose mural was never quite finished recalled: "I have worked just double as fast as the fastest; but I greatly feel the disadvantage of appearing in such company! And to work up to so rich a key of colouring is more than can be done hastily…Now I am approaching a very imperfect sort of completion, for I can give no more time to the thing. Rossetti and I worked on by gaslight until late” (270). Prinsep considered Pollen’s mural “was clearly the work of an amateur. Though showing greater cleverness of execution [compared to Morris], it was, artistically, the feeblest of the lot” (172).

Left: D. G. Rossetti’s mural Sir Launcelot's Vision of the San Grael. Photograph courtesy of Professor James Bump, University of Texas at Austin.

Rossetti’s Sir Laucelot’s Vision of the San Grael featured a sleeping Launcelot to the right, while to the left is the Damsel of the Grail, clasping the sacred vessel, and surrounded by her attendant angels. Between them the figure of Queen Guenevere rises in his dream, gazing at him and with her arms extended in the branches of an apple tree. She is seen clutching an apple, emphasising the symbolism with man’s first temptation and the original sin as told in the Book of Genesis, and making Launcelot’s sin more explicit. The adulterous relationship between Launcelot and Guenevere has been the cause of his failure to attain the Grail. This mural was halted unfinished when Rossetti was called away in mid-November because of a dangerous illness to Lizzie Siddal, who was then at Matlock in Derbyshire. The mural was never resumed.

The Blue Closet by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). 1857. Watercolour on paper, 14 x 10 ¼ inches (35.4 x 26.0 cm). Collection of Tate Britain, accession no. N03057

Part of the reason why Rossetti had not progressed further in his mural was the fact that he was working on his watercolours The Tune of the Seven Towers and The Blue Closet at that same time. Even in its unfinished state, however, it was surely the finest and most masterly of the murals. Pauline Trevelyan referred to Rossetti’s mural as “a most glorious piece of colour, & very beautiful besides” (Surtees 277). Rossetti never began the second mural he promised to do, generally thought to be of Sir Galahad, Sir Bors and Sir Percival Receiving the Sanc Grael (The Attainment of the Sanc Grael), although a design for it in pen and ink is in the collection of the British Museum. A watercolour sketch based on the design painted several years afterwards and now in the collection of Tate Britain gives some indication of how splendidly brilliant in colour the murals must have looked in their original state. There is some controversy, however, as to what the second and third murals were that Rossetti intended to execute. As late as June 1858, in a letter to Scott, Rossetti stated he was planning on going back to Oxford in the long summer vacation and paint his second mural of “Lancelot surprised in the chamber of Guenevere. There will be a third done, probably by Morris, from a design of mine, as a companion to the first, & representing the achievement of the Sancgrael by Galahad” (Rossetti Correspondence, letter 58.6, 212). A finished pen-and-ink drawing for Launcelot in Guenevere’s Chamber is in the collection of the Tate Britain.

Merlin and Nimue. Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones. 1857-58. The Oxford Union Library (formerly Oxford Union Debating Hall). Photograph courtesy of Professor Florence S. Boos, University of Iowa.

The subject of Merlin and Nimue seems to have fascinated Burne-Jones throughout his career. Nimue was “a lady of the lake” brought to King Arthur’s court at Camelot by King Pellinore. Merlin fell in love with her, taught her his magical crafts, and followed her to Cornwall when she left Arthur’s court. Nimue grew tired of his attentions, however, and being afraid of him lured Merlin to his death. Using an enchantment she had learnt from Merlin himself, she made him go under a great stone that he could never escape from despite all the magic craft he possessed. Burne-Jones‘s mural of Merlin Lured to his Death by Nimue wasn’t completed until February of 1858. As Spencer Stanhope recalled: "As time went on I found myself more and more attracted to Ned; the spaces we were decorating were next to each other, and this brought me closely into contact with him. In spite of his high spirits and fun he devoted himself more thoroughly to his work than any of the others with the exception of Morris; he appeared unable to leave his picture as long as he thought he could improve it, and as I was behindhand with mine we had the place all to ourselves for some weeks after the rest had gone" (Burne-Jones 164). Prinsep in his reminiscences considered Burne-Jones’s effort "The only one of real artistic merit…It was fine in colour, excellent in design, and entirely new in aspect" (172). Rossetti wrote “The best of the lot is Jones’s which is a perfect masterpiece in every way” (Correspondence, letter 58.6, 213) Other visitors to view the murals also considered Burne-Jones painting to be one of the best of the series. Pauline Trevelyan stated “Mr. Jones has a most beautiful figure of an enchantress with a lute, enticing Merlin into a wood where there is a little well &c – very nice – the lady is really very fine” (Surtees 278).

Stanhope’s mural of Sir Gawaine and the Damsels at the Fountain is based on the episode from Malory where Sir Gawaine accompanies his cousin Sir Ewaine, who had been banished from King Arthur’s court because of the treachery of his mother Morgan le Fay. In the Forest of Arroy they come across three women at a fountain. One of the women was aged sixty, the second was aged thirty with a circlet of gold around her head, while the last damsel was but fifteen years with a garland of flowers around her head. In Stanhope’s picture only Sir Gawaine is shown with the damsels, the youngest of whom is seen at the centre with her hair wreathed with flowers. The two older women are seen to the left with the fountain just visible behind.

The subject chosen by Prinsep to illustrate was The Love of Sir Pelleas for the Lady Ettarde. Gawaine, continuing his adventures, came across Sir Pelleas who was in love with the Lady Ettarde who has spurned his attentions. Gawaine offers to make her love Pelleas only to sleep with her herself. Pelleas come upon the lovers but chose not to kill them instead laying his sword across their throats. He swore he would die of sorrow but Nimue, the Lady of the Lake, cast an enchantment over Ettarde that caused her to love Pelleas whom she had previously hated. Pelleas rejected her and she died of a broken heart. In Prinsep’s mural Sir Pelleas is shown turning away from Ettarde in anger while to his left stands Nimue. Lady Trevelyan thought that “the figure of the lady who is being left is full of touching entreaty. The knight’s head is fine & manly the rest of him wasn’t painted” (Surtees 278).

Hughes’s mural of The Passing of Arthur shows King Arthur being received into a barge by the three queens who will take him to the Isle of Avalon, there to recover against his future coming. Arthur had been mortally wounded in the battle against his traitorous son Mordred. To the left of the composition, at the edge of the foreground, Sir Bedivere throws Arthur’s sword Excalibur into the lake where it is received by a mysterious hand. The death of Arthur was a popular subject for Victorian artists.

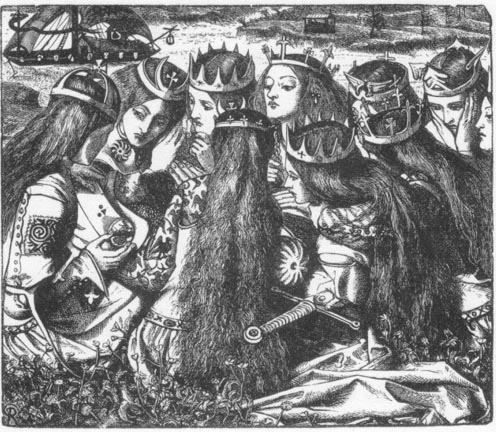

The Palace of Art. Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Engraved by the Dalziels. 1857. Wood engraving, 3.6 x 4.2 inches, Source: The Moxon Tennyson.

Rossetti had treated it previously in his illustration of “The Weeping Queens” for “The Palace of Art” in the Moxon Tennyson recently published in 1857. Hughes painted this subject as a moonlight scene, and while most people who viewed it considered it very successful, Ruskin did not. In a letter from Lady Trevelyan to m Scott of November 12, 1857 she writes: “Hughes has painted Arthur conveyed away in the boat, over the moonlight lake, & Sir Bevedere [sic] throwing Excalibur back into the water. I like it very much, but Mr. Ruskin does not he thinks it is not decorative enough and that a moonlight & an effect of light was not suitable, which perhaps is true, but it seems needful to complete the story, & the quiet of it seems to me pleasant & reposeful among all the blue skies, red haired ladies, and sunflowers. Several of the mourning ladies are very pathetic” (Surtees 278).

Munro’s relief in the tympanum of the porch to the Oxford Union entrance represented King Arthur and the Knights at the Round Table. It had the peculiarity of being coloured. Coventry Patmore remarked “Mr. Woodward and his pre-Raphaelite friends are clearly of the opinion that the use of colour in architecture may and ought to be revived to an extent at present almost undreamt of by most persons” (584).

Patmore’s Praise of the Murals and their Completion by the Rivieres

The murals must initially have presented a glorious appearance as can be ascertained from Coventry Patmore’s praise in The Saturday Review of 1857:

These paintings, which are in distemper, not fresco, promise to turn out novelties – and quite successful novelties - in art. We have not seen any mural painting which at all resembles, or, in certain respects, equals them. The characteristic in which they strike us as differing most remarkably from preceding architectural painting is their entire abandonment of the subdued tone of colour and the simplicity and severity of form hitherto thought essential in such kinds of decoration, and the adoption of a style of colouring so brilliant as to make the walls look like the margin of a highly-illuminated manuscript. The eye, even when not directed to any of the pictures, is thus pleased with a voluptuous radiance of variegated tints, instead of being made dimly and unsatisfactorily conscious of something or other disturbing the uniformity of the wall-surfaces. Those of our readers who have seen any of Mr. Rossetti’s drawings in water-colours will comprehend that this must be the effect of a vast band of wall covered with paintings as nearly as possible in that style of colouring…The colours, coming thus from points instead of from masses, are positively radiant, at the same time that they are wholly the reverse of glaring. An indefiniteness of outline – by no means implying any general dissolution of form – is a necessary result of Mr. Rossetti’s manner of colouring; but this result is one which seems to us to render it all the better suited for architectural painting…Mr. Rossetti and his associates have observed the true conditions and limitations of architectural painting with a degree of skill scarcely to have been expected from their inexperience in this kind of work. [584]

Unfortunately within a very few years the murals had deteriorated significantly, the result of having been executed in unsuitable materials upon poorly prepared walls and becoming obscured by dust and smoke. The hall initially was lit by naked gas-flames in large chandeliers so the smoke and heat generated by them went straight up on to the paintings. Over time the colours of the murals partly sank in, faded, blackened, and partly flaked off. Despite repeated attempts at restoration the murals exist today in a largely ruinous condition although their overall features are still recognizable.

The three unpainted panels that were left obviously troubled the Oxford Union authorities so they wrote to Rossetti to ask how much he would charge per panel to paint the rest. Inconclusive negotiations were carried out with Rossetti for about two years regarding the completion of his unfinished promised pictures. Finally in June 1859 the Oxford Union Committee hired William Riviere, assisted by his son Briton, to fill the three bays left vacant following the completion of the Jovial Campaign for a sum of £150. William Riviere had just become a teacher of painting in Oxford. The committee obviously wanted the architectural spaces to be visually complete because areas left unfilled next to the completed murals would have disrupted not only the visual continuity but also the narrative. The three murals they completed were The Education of Arthur and King Arthur’s First Victory with the Sword by William Riviere and King Arthur’s Wedding Feast by Briton Riviere. Val Prinsep considered “The pictures he added to what we did were, if anything, weaker than ours, and certainly lacked the something which our pictures possessed, namely, the excess of sentiment and lack of conventionality which commend the school of Rossetti to many thinking people” (172).

Notwithstanding the shortcomings of the murals they were to prove highly influential. John Christian, in his definitive writings on the murals, noted: “Although the venture can only be described as a failure, it remains the major contribution of Pre-Raphaelitism to the revival of large-scale mural painting, one of the most cherished ambitions of English art in the nineteenth century” (1). In spite of the young age and lack of experience of many of the artists involved in this project they all went on to distinguished careers as painters or designers. The importance of the Jovial Campaign, besides initiating the second phase of Pre-Raphaelitism, is that it also brought some individuals of merit into the orbit of the Pre-Raphaelite circle. The first was the undergraduate student Algernon Charles Swinburne of Balliol College, whose enthusiasm for Malory and the Arthurian legends made him a welcome visitor. Although he had already written poetry by then, he was soon to become one of Victorian England’s best-known and most notorious poets. The second person was Jane Burden, the seventeen-year-old daughter of an Oxford ostler, who Rossetti, Morris, and Burne-Jones discovered one evening sitting with her sister in a box above them when they attended a play at the Drury Lane Theatre in late September or early October. Rossetti asked her to model for him and his friends. Jane became Rossetti’s model for Guenevere, and Morris fell in love with her. Morris married her on 26 April 1859 and she became an accomplished embroiderer and assisted her husband in Morris & Co., embroidering items to his designs.

Bibliography

Burne-Jones, Georgiana. Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones. Volume 1. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd. 1904, 158-68.

Christian, John. The Oxford Union Murals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Doughty, Oswald: A Victorian Romantic. London: Oxford University Press, Second Edition, 1960, 224-42.

Glab, Tracee. “More Than Pictures”: Dante Gabriel Rossetti And The Oxford Mural Project. Wayne State University Thesis. Paper 56 (2010): 1-74.

MacCarthy, Fiona. The Last Pre-Raphaelite: Edward Burne-Jones and the Victorian Imagination. London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2011, 79-81, 84-85.

Mackail, J. W. Life of William Morris. Volume 1. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1905, 117-29.

Marsh, Jan. Dante Gabriel Rossetti Painter and Poet. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1999, 180-85.

Patmore, Coventry. “Walls and Wall Painting at Oxford.” The Saturday Review, 4 (December 26, 1857): 583-84.

Pollen, Anne. John Hungerford Pollen. London: John Murray, 1912.

Poulson, Christine. The Quest for the Grail. Arthurian Legend in British Art 1840-1920. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999.

Prinsep, Valentine Cameron. “A Chapter from An Artist’s Reminiscence. The Oxford Circle.” The Magazine of Art 27 (1904): 167-72.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Formative Years 1855-1862. Ed. William E. Fredeman. Volume 2. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2002.

Stirling, A. M. W. A Painter of Dreams. London: John Lane The Bodley Head, 1906, 312-17.

Surtees, Virginia. Reflections of a Friendship. John Ruskin’s Letters to Pauline Trevelyan 1848-1866. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1979. 277-78.

Last modified 24 November 2021