This review is reproduced here by kind permission of the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where it was first published. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee, who has also added the headings, captions and links. Click on the images for larger pictures and more information where available.

Here is an interesting and enjoyable book that is as valuable for the questions it raises as much as for what it actually says. Oliver Bradbury, a freelance architectural historian and the author of a study of the lost mansions of Mayfair, has written a book that describes how ideas derived from or inspired by one late eighteenth, early nineteenth-century neo-classical architect continued to flow somewhere in the background even during the period of the high gothic revival when his reputation was at its nadir. And yet the questions one finds oneself asking are: what was it that made John Soane's bizarre architecture so irresistible to his imitators? And what would have happened had there been no gothic revival?

Soane practised independently as an architect between 1781 and his death in 1837; the author has chosen 1791 as a starting date because it was in that decade that his idiosyncratic style reached maturity. He held two major public posts: one from 1788 as architect to the Bank of England, in succession to Robert Taylor and on the Bank's island site in the City of London; and from 1814 he was one of the Attached Architects to the Office of Works, from which position he designed extensions to government offices in and near Downing Street, as well as the "scala regia" to the House of Lords and a large law courts building adjacent to the old Palace of Westminster.

Left to right: (a) Sir John Soane's house and museum at Lincoln's Inn Fields. (b) Pitzhanger Manor House, Soane's country house at Ealing. (c) Dulwich Picture Gallery (1817).

Nearly all of this has vanished: in fact only some of the bank's outer walls and a few rooms in Downing Street, or merely fragments of them, survive, the latter something of a pathetic reminder of Soane's grand plans to redevelop the area completely to his own magnificent designs. These haunting schemes with their curious sail domes, their thin segmental arches, their mysterious indirect rooflighting, their peculiar "starfish" ceilings, are known only through Soane's own drawings and the poignant photographs of the Bank of England before and during their destruction in the 1920s. Yet they continue to exert fascination. What is left – Soane's own house and museum; the Dulwich Picture Gallery; various, mostly mutilated, country houses; and some other bits and pieces – is not much of a substitute for what has gone.

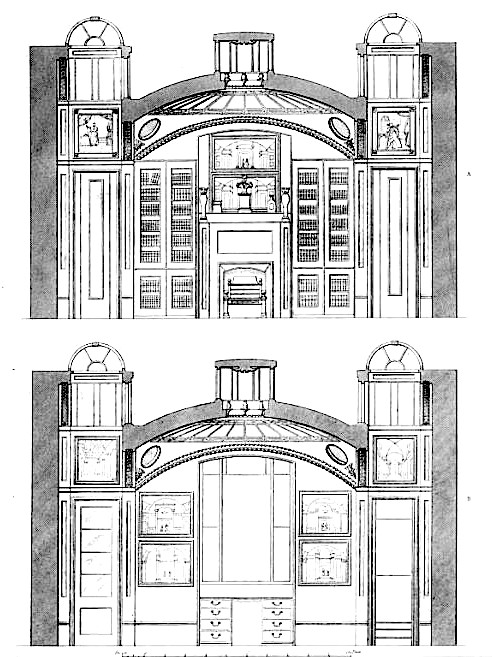

"Decoration, vaulting and top-lighting"

The Breakfast Room at Lincoln's Inn Fields. Left to right: (a) and (b) from its shallow dome, with its Greek key patterning surround, rises a small octagonal lantern. Source: Soane (1835), Plates etc., 1-3. (c) Looking south into one of Soane's typically curious spaces. Source: Soane (1832), Plate XXIX, facing p. 48.

Bradbury begins by defining the aspects of Soane's work that later architects imitated; the first of these categories is a broad one that includes most of what we would today recognise as Soanian: "Decoration, vaulting and top-lighting." Soane's decoration consisted of incised lines in simple rectilinear shapes, or a Greek key pattern; externally, he used acroteria abundantly, sometimes translated into a three-dimensional form and used as pinnacles. His most characteristic vaults were sail vaults – that is, they rose over a square space on pendentives (usually without any impost mouldings) to form a circular dome above which, at the Bank of England and elsewhere, a round glazed cupola might rise; but he also used groin vaults and, in his own house and at Downing Street a strange, starfish-like elongated variant of it. His top-lighting was generally indirect, for example from above the open sides of a sail vault. This was the arrangement in the breakfast room at his own house but at the law courts in particular he developed it with variations and frequent use of shallow segmental arches. Beyond this, Bradbury identifies Soane's church planning, his impact on the architectural profession, and his composition of facades as having later lives; and yet the book concentrates almost entirely on that first, mainly decorative category.

Soane's Pupils

Left: George Basevi's Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (1837-45). Right: Another pupil David Mocatta, designed Brighton Station in 1841. This picture was lithographed from his own drawing, by George Childs. Source: "View of the Brighton Station."

Bradbury's first task is to lay out the ways in which Soane's own pupils continued the style; sadly they were either noticeably lacking in talent or drive, or they came to an unhappy early end; perhaps Soane succeeded in knocking "feelings" out of them, as evidently he attempted to do. George Basevi, by some distance the most gifted, was killed in an accident at Ely cathedral in 1845, but not before having won the competition for the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Although altered during completion by C.R. Cockerell, this can be seen, as David Watkin has put it, as in effect a major late work "by Soane," the master whose influence Basevi was apparently already trying to escape. The railway architect David Mocatta was prolific but worked in an idiom that called little on Soane for its inspiration, and in any case nearly all of his buildings have been demolished. But the others had less to offer. George Allen Underwood also died young, at 36; his few pleasant houses and terraces in the spa town of Cheltenham are decorated with features that are superficially at any rate Soanian (or "Boeotian," to use the word employed insultingly at the time – the meaning of which was "dull" and "stupid" as well as from Boeotia in Greece). Soane's pupil and favoured perspective artist J.M. Gandy built little, but his work included a charming Soanian office building on Trafalgar Square, long gone.

Soane's — or Dance's — Imitators

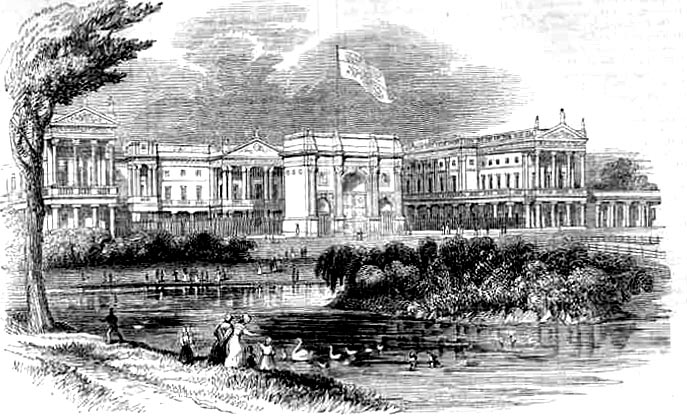

Left: Buckingham Place in 1841, with Nash's additions and Marble Arch in the courtyard. Right: Charles Barry's Manchester City Art Gallery of 1824-35.

In fact it seems that towards the end of Soane's life it was the great architects who borrowed from him: Nash, especially at Buckingham Palace; Jeffry Wyatville; Benjamin Latrobe, in Washington; Charles Barry; and even (and avowedly) Soane's own former pupil master George Dance the Younger. Or were they in fact borrowing from Dance? This is what Andrew Saint has suggested to the author, a plausible argument given that where these architects used sail domes or indirect lighting, or planned a tribune (a top-lit stair hall) in a large house as Soane often did, they seem to have avoided the weirder aspects of Soane's style. The latter, however, continued with a life of their own among anonymous builders in London and elsewhere. Bradbury points to the work of John Foulston in Plymouth as the most blatant of the Soane imitators. The incised patterns and acroteria-laden parapets were easy to copy; and Soane's layered brickwork arches, deployed at the stables he designed at the Royal Hospital in Chelsea in 1814-1817, were not only easy but cheap. They can be seen on a small scale all over the place in early-nineteenth-century London terraces, for example in Islington.

Late Nineteenth-Century Influence

Statue of Sir John Soane by Sir William Reid Dick, RA 1878-1961, unveiled in 1937, on the north wall of the Bank of England, Threadneedle Street, London EC2.

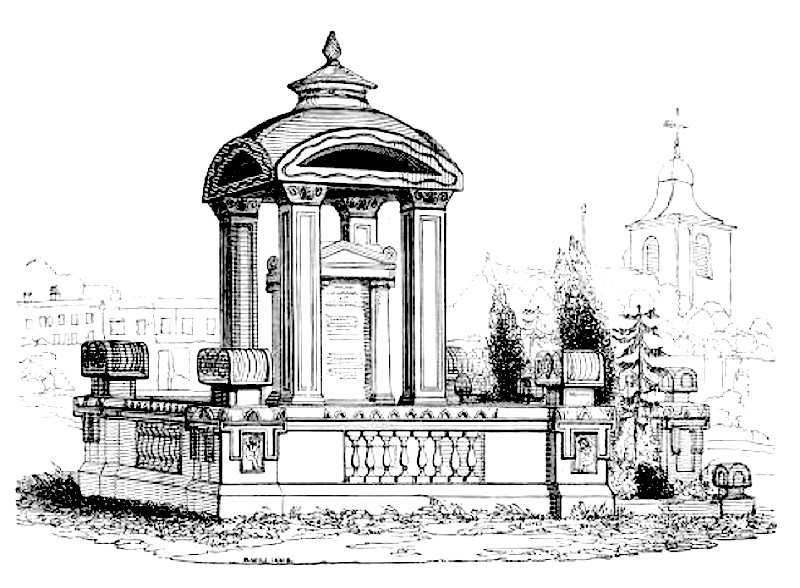

So, Soane goes underground in High Victorian London, and only emerges when young architects are tired of gothic. Here Bradbury's narrative speeds up somewhat and we move into much more familiar territory, of which only a brief overview is necessary here. Philip Webb, W.R. Lethaby, and even J. F. Bentley (at the clergy house of Westminster Cathedral) have been seen by some as channelling Soane, albeit surreptitiously; then, at the turn of the century, A. Beresford Pite starts to cite Soane directly, both at a large scale in his vaulted churches and on a tiny scale in details such as fireplaces. A little later, Edwin Lutyens designed a well-known kitchen for Castle Drogo in Devon with a Soanian dome, and H.S. Goodhart-Rendel a little-known drawing room for a small house in Surrey. Most modern Soane is internal work only. Herbert Baker, perhaps feeling guilty about presiding over the demolition of the Bank of England, simultaneously attempted Soanian interiors for a school dining room. In 1925 Giles Gilbert Scott made Soane's family tomb the model for his ubiquitous K2 public telephone kiosk. A.T. Bolton, the director of Soane's Museum, started to write more profoundly about Soane than anyone had attempted before; and after the Second World War, Bolton's successor John Summerson and the architect Albert Richardson continued the work. Raymond Erith did scaled-down "Soane" in his own Great House in Dedham and in his rebuilding of Downing Street; and, as a prolonged finale, Philip Johnson started to build Soanian ceilings all over the place: in a guest bedroom; in his Manhattan flat (in "shrimp pink and pistachio green"); in a Texan dining room; in a synagogue; wherever. The only aspect of this twentieth-century part of the story which might be unfamiliar is the use made of Soane's work by McMorran and Whitby: their Cripps Hall at the University of Nottingham (1957-1959), is illustrated here; its attenuated clock tower rising from a sculpted brick base bears a remarkable resemblance to the kitchen at Soane's now well restored Moggerhanger House in Bedfordshire.

Bradbury's language is a little odd in places and his chapter construction is most peculiar: the first one is very long, and the later ones much shorter, and Johnson inexplicably and quite disproportionately receives a tiny one almost to himself. The long chapter on the lesser-known Victorian houses is fascinating and full of valuable detail. But the continuing story is worthwhile too, for the story of Soane's continuing legacy is not just about the impact of one man: it confronts those two big questions of early-mid-nineteenth-century architecture.

Reputation

Left: Soane's family tomb in St Pancras old churchyard. Source: Soane (1835) 27. Right: Out of Order, David Mach's installation (1987) in Thames Street, Kingston-upon-Thames, plays on the iconic status of Giles Gilbert Scott's Soane-derived phone-box (now sometimes used for advertising purposes). Souce: photograph by JB.

Soane's reputational demise was not merely a matter of shifting fashion, or a change in generation: the gothic revivalists hated him more than anyone else and usually referred to him – rather than to the hapless and discredited Nash, or even the personally abhorrent James Wyatt – when they wanted a straw man for a target. Why Soane in particular? The obvious reason must be the importance of the quality of building construction to the revival. Soane's father was a bricklayer and the brick walls of his buildings are said to be of high quality; but the rest of them? Those vaults and hanging segmental arches that do nothing structurally, emphasised by pointless decorative incisions into plaster (like the scoring on the rind of a piece of pork, as was famously said at the time) – what are they made of, exactly, and how do they stay up? The moving force behind the revival and its professional success was what we now call "realism": the attempt to solve the evident problems of poor construction and lack of imagination in modern architecture by first of all expressing or even exaggerating the physical nature and function of materials, joints and junctions; and, secondly, by emphasising the purpose of a room in its outward form and planning. Soane's architecture did none of these things. His famous Bank of England Old Four Per Cent Office was for the revivalists nothing but a vast blown-up version of his breakfast room. And Soane himself was a bad-tempered hermetic, a freemason; easily angered and provoked; easily made to look stupid. It was the gothic revivalists and their various allies in the profession and in the Church of England who more or less invented the vicious culture of personal abuse as a form of architectural criticism and the death in 1837 of the litigious Soane – forever waging and losing legal battles over his reputation – made it all the more rewarding to direct it in particular against him.

"The Architecture of Death"

The house as museum, complete with Egyptian sarcophagus in the basement. Source: Soane (1832), facing p. 43.

But that is only part of the story. The other part is that Soane's architecture then as today looked like the architecture of death. His tomb, familiar from its endless repetition in the form of that telephone kiosk, and his Picture Gallery mausoleum are blatantly morbid, but then so is much else: the sepulchral indirect lighting; the unexplained labyrinthine plans; his strange pagan symbolism and iconography; his interest in the architecture of ancient Egypt; perhaps even his association with Gandy, a debtor incarcerated in a lunatic asylum obsessed by apocalyptic visions of ruins. It is obvious – and it was explicit at the time – that the gothic revivalists promoted their work by contrast as the architecture of redemption. Pugin was able to make an argument for his gothic churches that credibly used the language of Christianity – truth, honesty, morality, and so on – to describe what he was doing not only because those were the words of the clients he most wanted to please, and not only because of his own piety, but because the buildings suddenly soared upwards: look at his early church of St Mary's, Derby, in the context of the recent squat and clumsy efforts by his contemporaries in the same town and you can quickly see why one critic found it "painfully" beautiful. There was a great deal in Pugin's writing – in fact, there is an explicit description in his 1841 text The Present State – about the morally and physiologically uplifting qualities of stained glass windows that faced the sun, but there is quite a bit also about how these are necessarily the properties of gothic architecture of all kinds.

And thus emerge the two intriguing questions that this book suggests without actually mentioning. Why did an architecture of death have any continued appeal? And what would have happened if England had never had a gothic revival? The answer to the first question must surely be that the assertive optimism of the gothic revival is not for everyone. As well as inventing a caustic, ad hominem methodology for shaming opponents, it was the gothic revivalists who succeeded in establishing the idea that architecture should be judged in binary and simplistic terms; that there is "good" and "bad" in architecture just as there is "truth" and "morality" in it. But not everyone sees architecture like this: for some, buildings can be memorials, and not always in a good way; for others, the power of them lies in their inexplicability or illogicality. Johnson, surely, tried to provoke and annoy other architects and Bradbury tells us that Mies van der Rohe was so appalled by that guestroom ceiling that he refused to sleep there. One of the intriguing aspects of the Regency revival of the early twentieth century is that those who did the reviving knew that this was a "doomed" style: they were aware that it had been wiped out from the front line of architecture by the gothic revival. It was almost synonymous with failure and to adopt it was to signal defiance of the aging leaders of the profession and all that they stood for. But the answer to the second question is less clear. Had there been no gothic revival, how then would our neo-classicism have looked? Would our young British architecture students today be learning about Schinkel or Semper? As it is, they know nothing of them. Or would Soane and his morbid gloom have shaped our cultural personality instead of the sunlit uplands of the gothic revival and the "arts and crafts"?

Bibliography

Book under Review: Bradbury, Oliver. Sir John Soane's Influence on Architecture from 1791: A Continuing Legacy. Farnham: Ashgate, 2015. Hardcover. xxiv + 455p. ISBN 978-1472409102. £95.00.

Sources of illustrations not already in the Victorian Web or given above:

Soane, John. Description of the Residence of Sir John Soane, Architect. Privately printed copies of 1832 (Google Books) and 1835 (Internet Archive, contributed by the Getty Research Institute). Web. 6 April 2015.

"View of the Brighton Station." Wikimedia. Web. 6 April 2015.

Created 6 April 2015