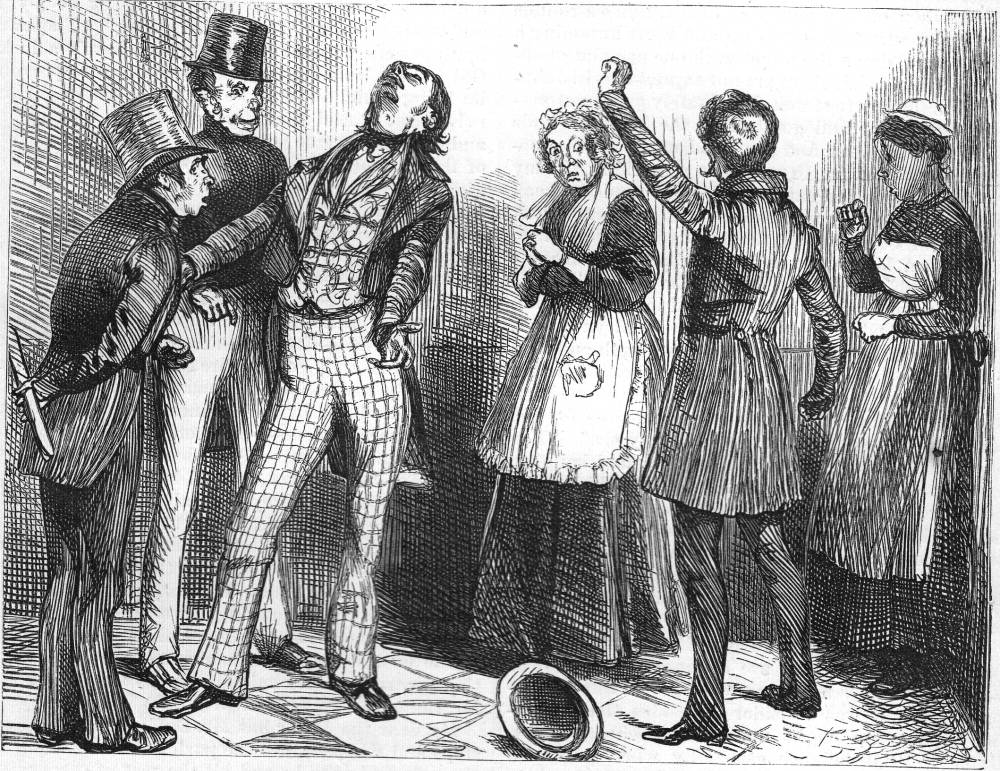

"Come sir! Remove me to my vile dungeon. Where is my mouldy straw?" by E. A. Abbey. 10 x 13.2 cm framed. From the Household Edition (1876) of Dickens's Christmas Stories, p. 217. The illustration originally appeared in "Chapter One: Mrs. Lirriper Relates How She Went on, and Went Over" from Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy in the December 1864 All the Year Round. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Coming from the rhetorical school of hyperbole, Mrs. Lirriper's young brother-in-law, Joshua, resembles both Wilkins Micawber of David Copperfield, and Charles Dickens's own father, John, a naval pay office clerk with a fondness for luxury and rhetorical figures. A further point of correspondence, about which Abbey, having in all likelihood read John Forster's Life of Charles Dickens would have been aware, was Joshua's being apprehended for debt by special constables. Indeed, this is the serio-comic moment that Abbey has realized in Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy (December 1864), the sequel to Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings in All the Year Round (December 1863).

Passage Illustrated on Facing Page

My dear it gave me such a dreadful turn to think of the brains of my poor dear Lirriper's own flesh and blood flying about the new oilcloth however unworthy to be so assisted, that I went out of my room here to ask him what he would take once for all not to do it for life when I found him in the custody of two gentlemen that I should have judged to be in the feather-bed trade if they had not announced the law, so fluffy were their personal appearance. "Bring your chains, sir," says Joshua to the littlest of the two in the biggest hat, "rivet on my fetters!" Imagine my feelings when I pictered him clanking up Norfolk Street in irons and Miss Wozenham looking out of window! "Gentlemen," I says all of a tremble and ready to drop "please to bring him into Major Jackman’s apartments." So they brought him into the Parlours, and when the Major spies his own curly-brimmed hat on him which Joshua Lirriper had whipped off its peg in the passage for a military disguise he goes into such a tearing passion that he tips it off his head with his hand and kicks it up to the ceiling with his foot where it grazed long afterwards. "Major" I says “be cool and advise me what to do with Joshua my dead and gone Lirriper’s own youngest brother." "Madam" says the Major “my advice is that you board and lodge him in a Powder Mill, with a handsome gratuity to the proprietor when exploded." "Major" I says “as a Christian you cannot mean your words." "Madam" says the Major "by the Lord I do!" and indeed the Major besides being with all his merits a very passionate man for his size had a bad opinion of Joshua on account of former troubles even unattended by liberties taken with his apparel. When Joshua Lirriper hears this conversation betwixt us he turns upon the littlest one with the biggest hat and says "Come sir! Remove me to my vile dungeon. Where is my mouldy straw?" My dear at the picter of him rising in my mind dressed almost entirely in padlocks like Baron Trenck in Jemmy's book I was so overcome that I burst into tears and I says to the Major, "Major take my keys and settle with these gentlemen or I shall never know a happy minute more," which was done several times both before and since, but still I must remember that Joshua Lirriper has his good feelings and shows them in being always so troubled in his mind when he cannot wear mourning for his brother. Many a long year have I left off my widow's mourning not being wishful to intrude, but the tender point in Joshua that I cannot help a little yielding to is when he writes "One single sovereign would enable me to wear a decent suit of mourning for my much-loved brother. I vowed at the time of his lamented death that I would ever wear sables in memory of him but Alas how short-sighted is man, How keep that vow when penniless!" It says a good deal for the strength of his feelings that he couldn't have been seven year old when my poor Lirriper died and to have kept to it ever since is highly creditable. [216]

Although the plot of this sequel revolves around Mrs. Lirriper's travelling to Sens in France to learn the identity of an Englishman who died there, leaving her a legacy, Joshua Lirriper, her deceased husband's much younger brother, something an alcoholic and wastrel, affords much comic relief as Mrs. Lirriper's rambling, unpunctuated dialectal narrative (anticipating that of James Joyce's Molly Bloom in Ulysses) communicates her warm-hearted, philanthropic nature. Although the composition of the theatrical scene is complicated, the reader of the American Household Edition, having already encountered the comic scene in the text on the previous page, would have recognised it easily since its positioning makes it subject to an "analeptic" reading — that is, the reader, having experienced the textual material beforehand has a grasp of the characters and the circumstances. Whereas Dickens has Mrs. Lirriper recount the arrest as a first-person retrospective, Abbey makes the action dramatic; however, he maintains the focus on Mrs. Lirriper's judgement about the situation by placing her (with disconcerted expression) at the centre of the somewhat theatrical composition.

Commonly in Abbey's illustrations there are just three subjects, permitting the artist to establish a context through including some background details. Here, however, the caption and Joshua's posture establish the context by referring the reader back to the textual passage on the previous page. The composition is rather crowded, but Abbey has individualised each of the six figures through their poses, costumes, and expressions. Mrs. Lirriper and her brother-in-law are centre, Joshua clearly identified by his histrionic pose. The short and tall bailiffs, with similar hats and neanderthal faces, watch from the left; Major Jackman, incensed at Joshua's conduct, has his back towards the viewer, just having kicked his own hast, which served as an element of Joshua's disguise (an inept attempt to escape the bailiffs) and now lies on the floor. The remaining figure (far right) is Mrs. Lirriper's "girl," that is, her downstairs maid, who customarily answers the door and in this instance has just admitted Joshua and his pursuers. The setting could as easily be a corridor as in Major Jackman's apartments, for Abbey has provided no contextual clues such as draperies, furnishings, or pictures to establish that we are in the parlour. Abbey pleasantly varies the disposition of the figures by having the put-upon Joshua look up to Heaven and by grouping the three figures to the left (as one would expect, the special constables stick close to the subject of their warrant), while bringing Jackman forward and having him face the ladies, upstage (so to speak) in this micro-drama. With her obvious look of discomfort, emphasized by her gripping of her hands and wide-eyed anxiety engendered by Jackman's response and Joshua's hyperbolic utterances, as well as by the presence of bailiffs in the house, Mrs. Lirriper is one of two focal characters; the other is the hyper-emotional Joshua, distinguished by a flowered waistcoat of the type Dickens himself favoured, and the type of checked trousers in fashion in the 1860s, although almost identical to Bob Cratchit's in Abbey's Christmas Carol illustrations "Went down a slide on Cornhill twenty times in honor of its being Christmas-Eve" (p. 14) and "'Mr. Scrooge!' said Bob; 'I'll give you Mr. Scrooge, the founder of the feast!" (p. 28).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting, color correction, and linking by George P. Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 7 December 2012