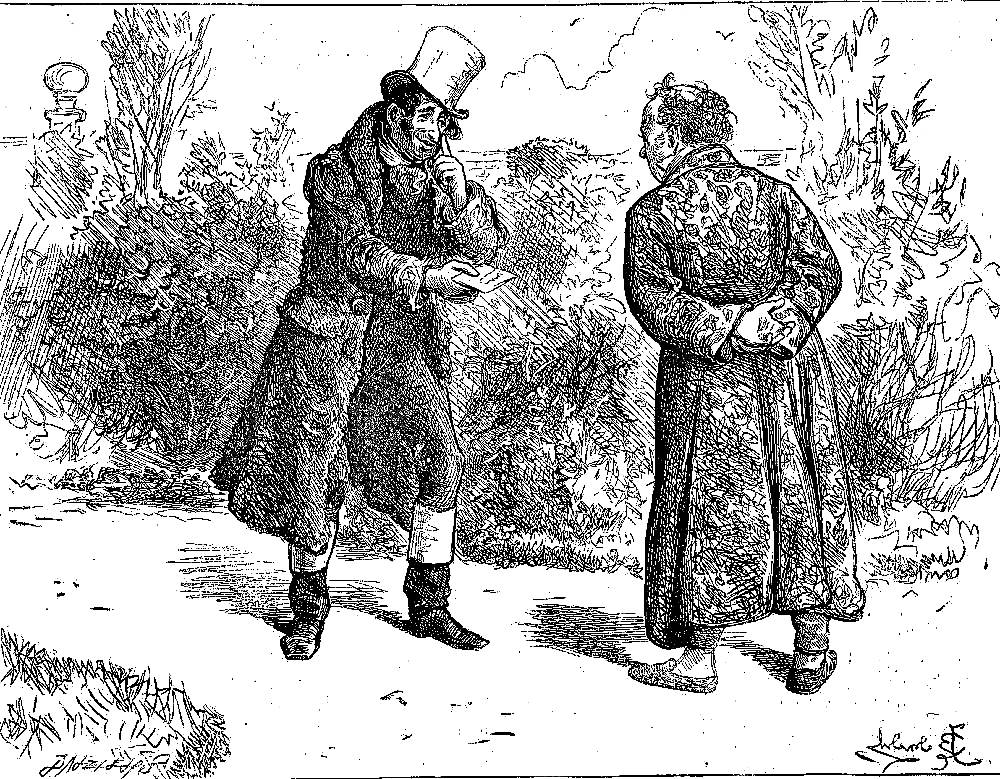

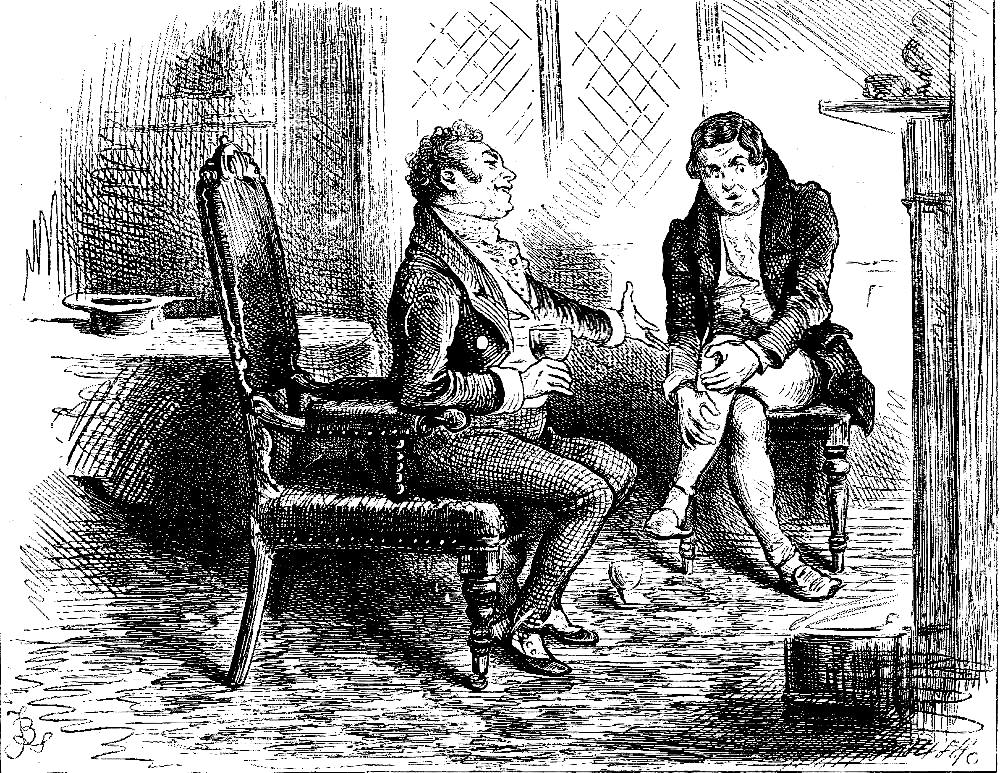

"I've brought this here note," replied the individual in the painted tops in a hoarse whisper; "I've brought this here note from a gen'l'm'n as come to our house this mornin'." (wood-engraving). 1876. 10.6 cm high x 13.7 cm wide, framed. — Fred Barnard's realistic response to the pathetically humorous, two-part short story. This, the second of two illustrations for this story that Barnard prepared for Household Edition parallels the first of three copper-engravings that Dickens's chief illustrator at this point, George Cruikshank, produced for the Chapman and Hall one-volume edition of Sketches by Boz (1839). In The Lock-up House, the first of two illustrations for the second part of the story, Cruikshank represents the dubious social stratum into which Watkins Tottle has fallen as a consequence of his debts. Here, Barnard shows the scene in which, through a deputy of the lock-up house Tottle appeals to his friend and sponsor, Gabriel Parsons, for assistance.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

"Time Tottle was down," said Mr. Gabriel Parsons, ruminating — "Oh, here he is, no doubt," added Gabriel, as a cab drove rapidly up the hill; and he buttoned his dressing-gown, and opened the gate to receive the expected visitor. The cab stopped, and out jumped a man in a coarse Petersham great-coat, whity-brown neckerchief, faded black suit, gamboge-coloured top-boots, and one of those large-crowned hats, formerly seldom met with, but now very generally patronised by gentlemen and costermongers.

"Mr. Parsons?" said the man, looking at the superscription of a note he held in his hand, and addressing Gabriel with an inquiring air.

"My name is Parsons,"responded the sugar-baker.

"I've brought this here note,"replied the individual in the painted tops, in a hoarse whisper: "I've brought this here note from a gen'lm'n as come to our house this mornin'."

"I expected the gentleman at my house," said Parsons, as he broke the seal, which bore the impression of her Majesty’s profile as it is seen on a sixpence.

"I've no doubt the gen'lm'n would ha' been here," replied the stranger, "if he hadn’t happened to call at our house first; but we never trusts no gen'lm'n furder nor we can see him — no mistake about that there" — added the unknown, with a facetious grin; "beg your pardon, sir, no offence meant, only — once in, and I wish you may — catch the idea, sir?"

Mr. Gabriel Parsons was not remarkable for catching anything suddenly, but a cold. He therefore only bestowed a glance of profound astonishment on his mysterious companion, and proceeded to unfold the note of which he had been the bearer. Once opened and the idea was caught with very little difficulty. Mr. Watkins Tottle had been suddenly arrested for 33£. 10s. 4d, and dated his communication from a lock-up house in the vicinity of Chancery-lane.

"Unfortunate affair this!" said Parsons, refolding the note.

"Oh! nothin' ven you’re used to it," coolly observed the man in the Petersham.

"Tom!" exclaimed Parsons, after a few minutes' consideration, "just put the horse in, will you? — Tell the gentleman that I shall be there almost as soon as you are," he continued, addressing the sheriff-officer's Mercury. — Chapter 2 of "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," running head: "Mr. Solomon Jacobs's," p. 214.

Commentary

Comic account of an impoverished middle-aged bachelor's attempt, initiated and organized by his prosperous friend, Gabriel Parsons, to capture the affections of a prim, well-to-do spinster, Miss Lillerton. During the course of the story Tottle is arrested for theft [actually, debt] and taken to a sponging-house, from which he is rescued by Parsons. — The Dickens Index, p. 191.

Just when the enterprising Mr. Gabriel Parsons, sugar-baker, believes that he has found the solution to Watkins Tottle's financial problems (to say nothing of a 33£. debt Tottle owes him) comes a dire complication: Tottle has been apprehended for debt, and is being held in a lock-up house, prior (presumably) to being transferred to the Marshalsea in Southwark. The short scene in which the sheriff-officer's "Mercury" (confidential messenger) delivers Tottle's explanation of his changed circumstances is a fine example of Dickens's ability to create a character in brief space through idiosyncratic dialogue.

Charles Dickens's father, John, must have been held in just such a situation when he was arrested for debt of 40£, including costs (and therefore a sum similar to that owed by Watkins Tottle), and prior to his being incarcerated in the Marshalsea Prison, Southwark, on 20 February 1824, just after Charles Dickens's twelfth birthday. Undoubtedly, as Michael Slater remarks, Charles made "a close study . . . of his father's fellow-prisoners in the Marshalsea" (23) which would serve him well when writing this scene, as well as those in which Samuel Pickwick is incarcerated in the Fleet Prison. Whereas in the original anthology George Cruikshank depicted the interior of Tottle's place of temporary confinement in The Lock-up House, Fred Barnard in the Household Edition has elected to depict instead the moment when Parsons learns of Tottle's misfortune from Solomon Jacobs' agent. The expectation is, of course, that the wealthy Parsons will wish to bail his friend out. The earlier illustration by Cruikshank, The Broker's Man also concerns the issue of a gentleman's being dunned for debt, and the "mercury" here is definitely of the same "knowing" tribe as this earlier functionary.

Harry Furniss has elaborated on the figure of the cocky messenger in his 1910 lithograph The Sheriff-Officer's Mercury. As is more typical of Barnard's artistic tendencies, however, this wood-engraving is essentially a dual character study of the messenger in his white top-hat (reminiscent of that of the housebreaker Bill Sikes in his illustrations for Oliver Twist, notably Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends) and Petersham greatcoat and topboots is exactly as Dickens has described him, with several noteworthy additions: his eyebrows raised in questioning the identity of his interlocutor, the mercury smiles affably and holds an index finger to his nose, as if communicating the information to a knowing auditor. The recipient of the note, in his flowered dressing-gown and slippers, clearly was not prepared to receive visitors so early — he has not even combed and brushed his hair. Barnard requires that we infer Parsons' facial expression from the text and the nature of the news conveyed by the disreputable messenger, but has sketched in sufficient background detail to reveal that the conversation occurs in Parsons' garden in Norwood, a comfortable suburb southeast of London. Since the story is set in 1835, Barnard would have been aware of the rapid development of the area in the 1830s, following architect Decimus Burton's designing a pleasure garden and spa below Beulah Hill in 1831, making the area fashionable for the newly-rich middle class, of which Gabriel Parsons and Miss Lillerton are members. This is precisely the class that Watkins Tottle hopes to join through a favourable marriage, for the opening of the story makes it clear that in imagination he transforms his little room in Cecil Street, Strand, "into a neat house in the suburbs" (207), a house very much like that owned by Gabriel Parsons, the complacent, middle-aged bourgeois in the fashionable dressing-gown in Barnard's illustration.

Illustrations from the 1839 and Other Editions for "Watkins Tottle"

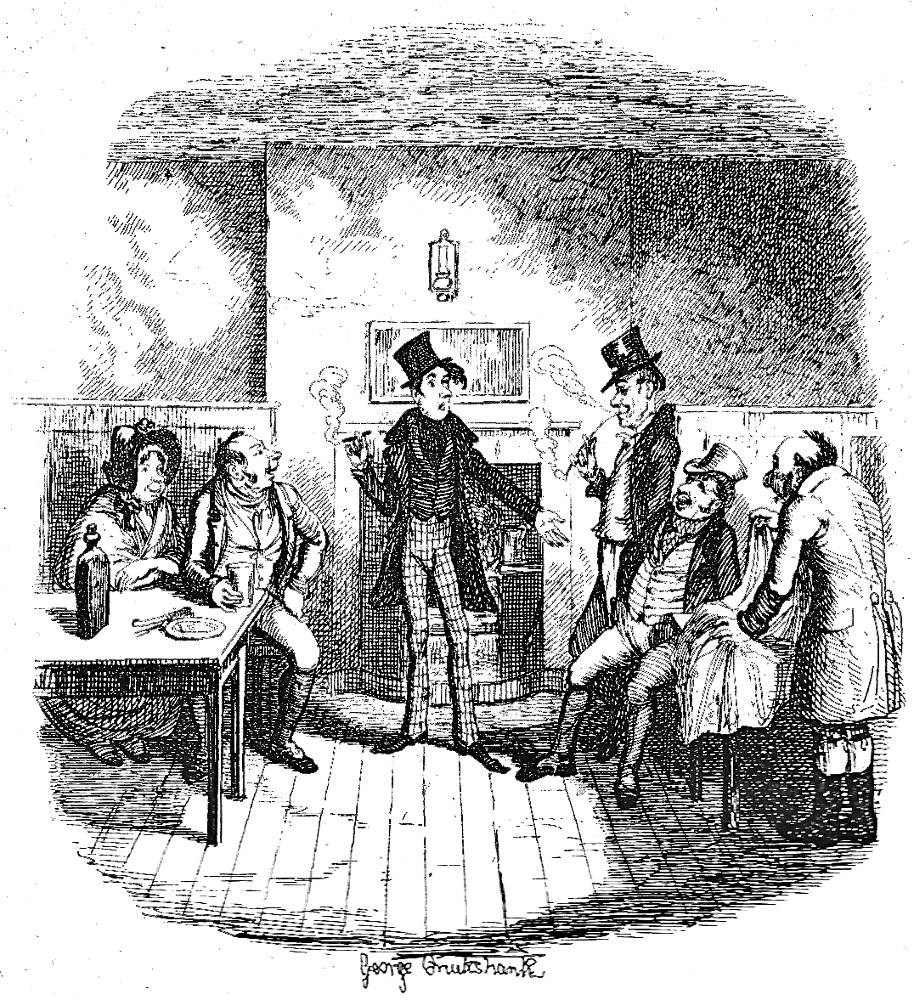

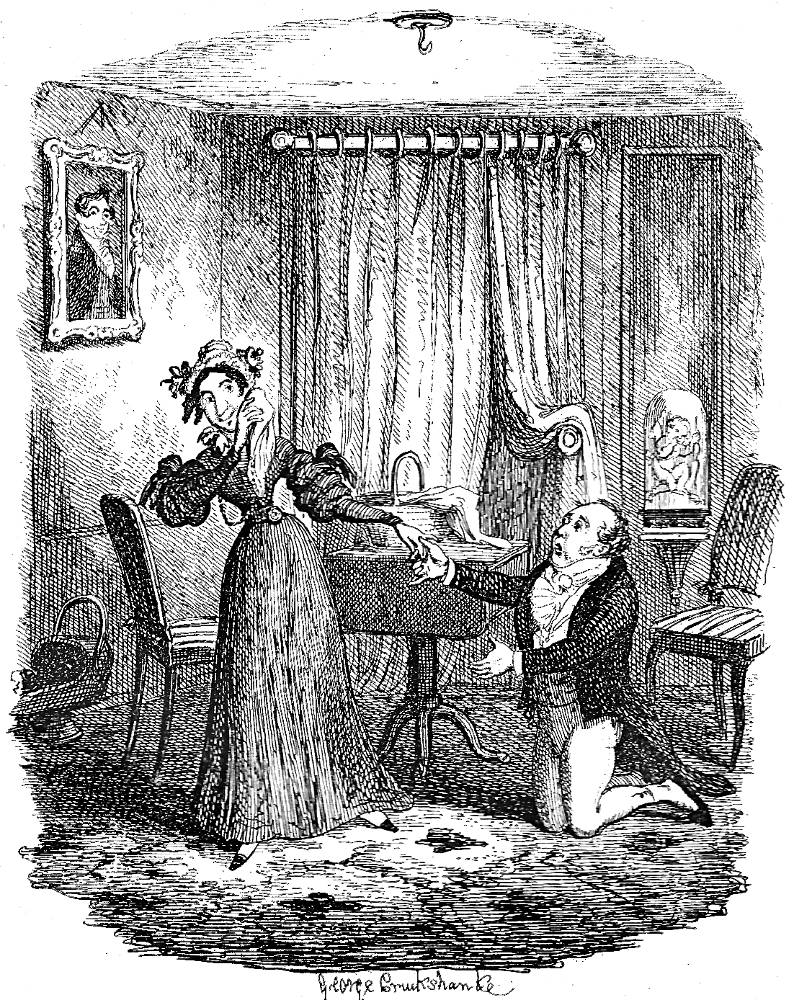

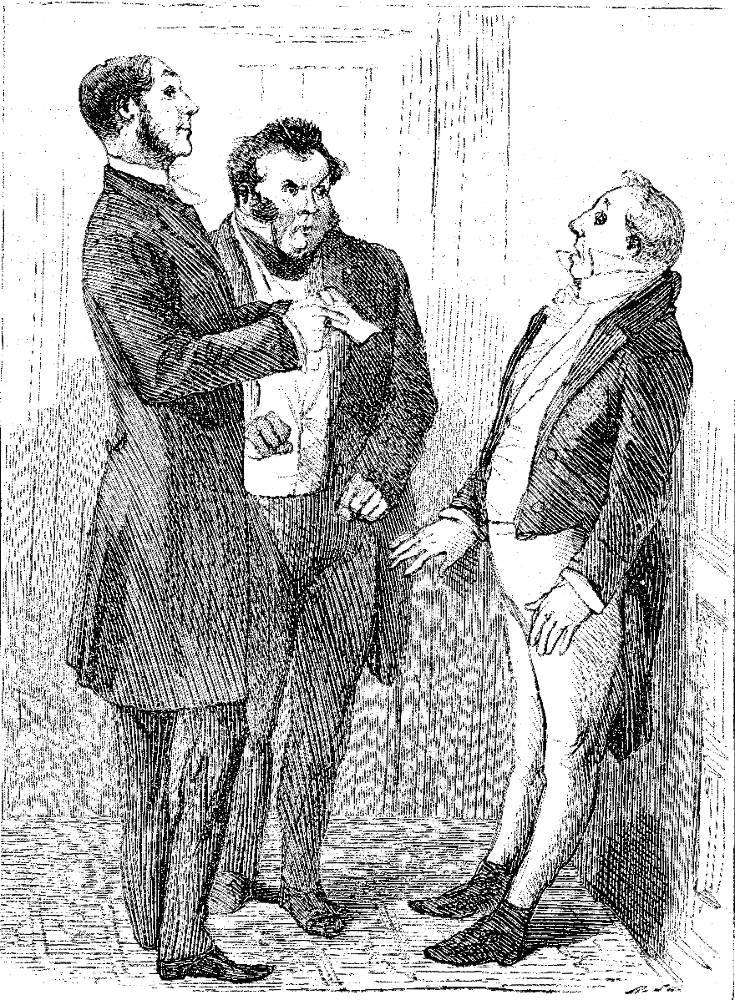

Left: Cruikshank's second illustration for the story, showing the plot complication of Tottle's being arrested for debt as he is preparing to court Miss Lillerton, The Lock-up House in "Chapter the Second." Left of centre: Cruikshank's third illustration, which misleadingly suggests that Tottle will be successful in his courtship of the affluent spinster, Mr. Watkins Tottle and Miss Lillerton. Right of centre: Eytinge's single illustration, featuring Tottle (right), Rev. Timson (lefty), and Parsons (centre), as they learn of Miss Lillerton's engagement to the Anglican minister, Mr. Watkins Tottle (1867). Right: Furniss's realisation of the agent of the lock-up house, The Sheriff-Officer's Mercury (1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

The Initial Illustration of the Story in The Household Edition (1876)

Above: Fred Barnard's wood-engraving of the same situation in the two-part short story, "Why," replied Mr. Watkins Tottle, evasively; for he trembled violently, and felt a sudden tingling throughout his whole frame; "Why — I should certainly — at least, I think I should like —" — to marry the wealthy spinster, Miss Lillerton. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z. The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 326-55.

Dickens, Charles. "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor and Fields edition]. Pp. 465-85.

Dickens, Charles. "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 115-117.

Dickens, Charles. "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1. Pp. 419-55.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall,1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp.1-28.

Schlicke, Paul. "Sketches by Boz.Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 530-535.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Last modified 3 June 2017