This is a lightly edited version of an essay that first appeared in the PRS Review special edition, ‘Forgotten Pre-Raphaelites,’ 31:3 (Autumn 2023). Reproduced with permission of the author and editor. Click on the first four images for more information about then, and to see larger pictures.— Simon Cooke

n 1897, a twenty year old Frank Cadogan Cowper enrolled as a student at the Royal Academy Schools. He had previously been educated at Cranleigh, before going on to study at St. John’s Wood Art School. His precocious talent for drawing had been fostered by his parents, both authors, although his father also illustrated some of his own books. In London, Cowper met a coterie of like-minded artists, fired by the romance of a bygone age, and inspired by the art and literature of previous generations. In 1898, the Royal Academy staged two important retrospective exhibitions – one devoted to the works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and another to the works of John Everett Millais. These two exhibitions would have a marked impact upon Cowper and his student friends, presenting works of art that they would venerate and, to a certain extent, imitate. For Cowper, the early works of the Pre-Raphaelites would become the first major influence in his development as an artist, and although his idiosyncratic style of painting and choice of subjects would evolve through successive decades, this early influence would continue to underpin his work right up until his death in 1958.

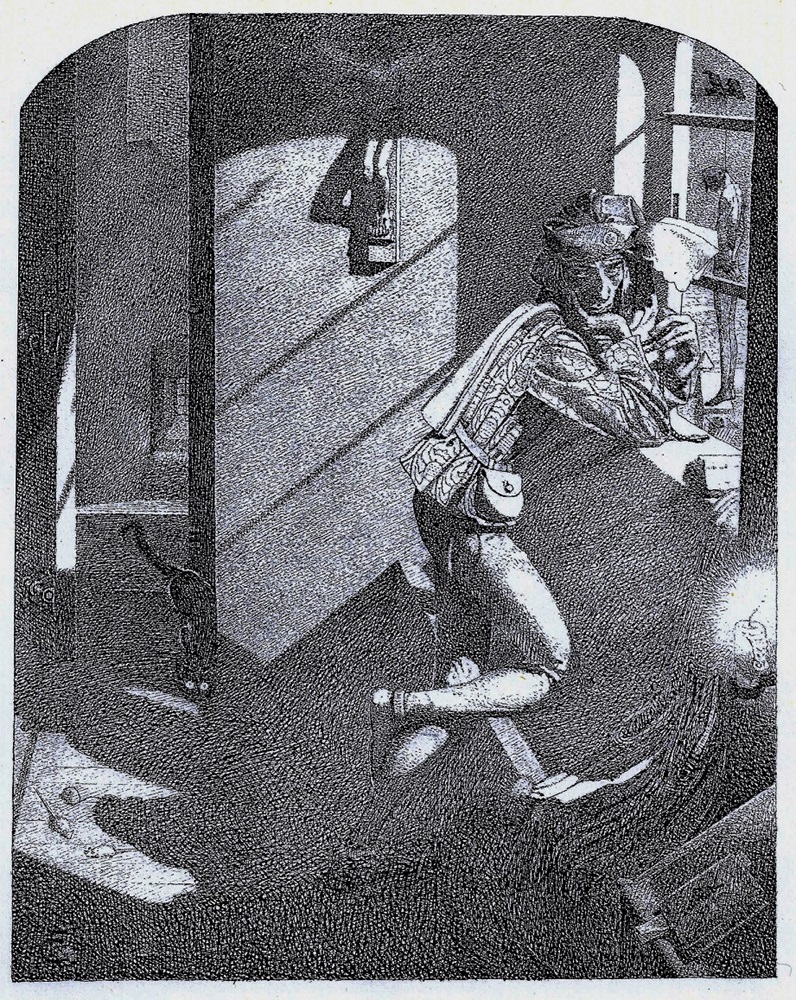

King Louis XI of France.

A Pre-Raphaelite attention to detail is obvious in the work that Cowper created at around this time. His arched-topped drawing of King Louis XI of France was published in The Idler magazine in 1899 – a dark and sinister portrayal of the mediaeval French monarch, perched between a half-lit crucifix on the wall behind him, and a hanged corpse outside the window (The Idler 588). Louis XI’s reputation as a paranoid recluse, fearful of being murdered by his subjects, was borne out by reports of courtiers seen hanging from trees in the gardens of the castle of Plessis-les-Tours. The king’s contorted crossed leg pose is reminiscent of a figure in Rossetti’s drawing of The First Anniversary of the Death of Beatrice (Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery), whilst his shadowed face is imbued with a brooding melancholy, as his bony fingers fondle the beads of a rosary. Three unwitting mice, picked out by moonlight, are approached by a black cat, its eyes glowing in the direction of the viewer. A shadowed object, possibly a small crown, to the left of the composition, resembles Millais’s monogram – almost certainly a humorous nod to Cowper’s Pre-Raphaelite predecessor. And upon a ledge sits a closed book of prayer, reminding us again of the king’s religious fervour.

Cowper’s principal source is undoubtedly Victor Hugo’s description of ‘the retreat where Monsieur Louis de France says his prayers’ (222–225). Hugo chronicles the sparse contents of the chamber within the topmost storey of the Bastille, feeding Cowper’s imagination and guiding his pen:

There was only one window, a long pointed casement, latticed with brass wire and apartments, neither benches, nor trestles, nor forms, nor common stools in the form of a chest, nor fine stools sustained by pillars and counter-pillars, at four sols a piece. [Hugo 223]

He also describes the king in unflattering terms, with ‘his body ungracefully doubled up, his knees crossed, his elbow on the table, a very badly accoutred personage’ (224).

Cowper’s depiction of the king owes some debt to contemporary illustrations to Hugo’s text, but relies more upon the author’s descriptive prowess and Cowper’s own imagination to construct the scene. In terms of comparable Pre-Raphaelite imagery of the subject, Cowper was probably unaware of Rossetti’s sketch of Charles Keane as Louis XI (Private Collection, Fredeman Plate 65), or Eyre Crowe’s Louis XI at Sainte-Chapelle, Paris (Private Collection). Apart from the title, no text accompanied the image when it was first published, although it was later reproduced in The Studio magazine where it was described as ‘an early example of that artist’s accomplished draughtsmanship – it was, we believe, executed when he was a student at the R.A. Schools – and though destined to appear in the now defunct Idler has not, we think, been published before’ (Studio, 1923, 44). The drawing was then in the possession of Mr H. Danielson, whereas the owner of the copyright was Sidney H. Sime, former editor of The Idler, himself an artist whose work at times was redolent of the Louis XI drawing. Cowper went on to provide illustrations for two further editions of the short-lived magazine, but none of them had the impact of the present image.

Cowper favoured an arched-top composition not just for his archaic drawings, but also for his paintings, using the same format in several of his exhibited canvases. These included The Good Samaritan, which was to feature in a revised edition of Percy Bate’s The English Pre-Raphaelite Painters and Hamlet – the churchyard scene, for which the artist had a large hole dug in his front garden, so that he could perfectly replicate in paint the subtleties of a newly dug grave (Royal Academy Summer Exhibition 1902, No. 507). A self-portrait, painted in 1899, intended for that year’s Royal Academy exhibition retains a trace of its arched-top border, despite now being framed without its original slip. Cowper gazes out confidently through a pair of pince-nez spectacles, sporting a high collar that he continued to wear long after they had gone out of fashion.

Cowper’s self-portrait of 1899.

This visible self-assurance is reflected in a letter that he wrote to his mother at about this time:

Now I feel what I never felt before and that is confidence in painting, because I have got a method and understand it. Certainly, Eden and I understand the theory of Pre-Raphaelitism perfectly now, and as far as the method of painting is concerned, we understand it better than all the P.R.B. (except Millais) did themselves, and Millais either painted in the proper way unconsciously because it came easiest without knowing why, or else he understood it thoroughly, having found it out from the early Italians (as Eden has done) and was a beast and kept it to himself. I think this is not unlikely, because Millais must have looked upon Rossetti and Hunt as rivals, as though they were all upholding the same theory of Art [Letter dated 13 August 1899. Royal Academy Archives, COW 2/1]

The bold assertion that Cowper and his artist friend William Denis Eden understood the Pre-Raphaelite method of painting better than the Pre-Raphaelites was illustrated by a string of successful Royal Academy exhibits, and prompted an announcement a few years later that they had formed ‘A Brotherhood, which, in a modest way, endeavours to work with the same ideals that inspired the original P.R.B’ (The Art Record, 733.) This new realisation seems to have directed Cowper’s focus away from producing illustrations, however two further significant black and white works were produced, before he completely immersed himself in the world of colour.

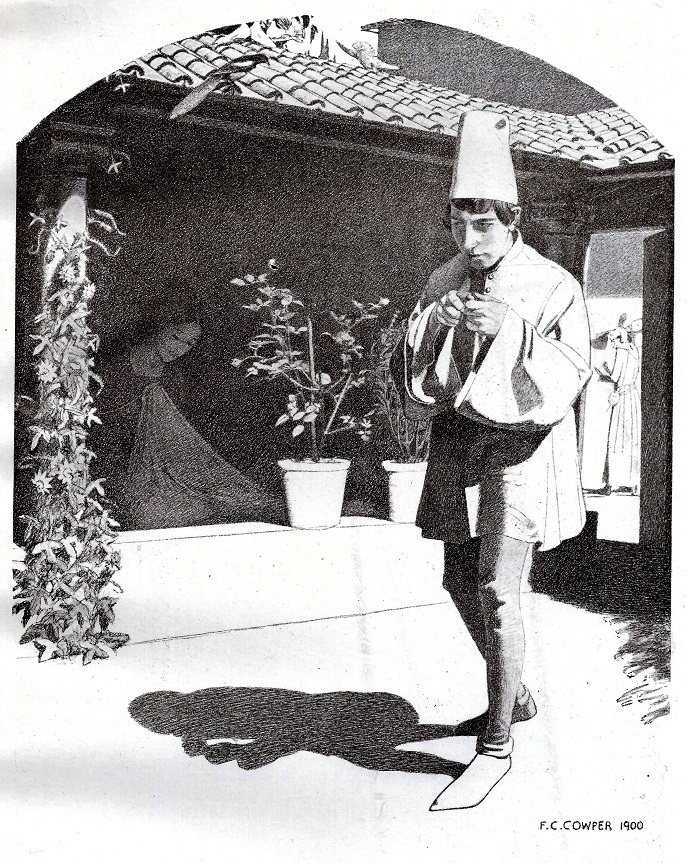

Lorenzo and Isabella.

A detailed pen and ink drawing, which Cowper began working upon at the same time as the self-portrait, shares the arched-top format, the subject being Lorenzo and Isabella (see letter to mother, 17 February 1899, Royal Academy Archives, COW 1/1). Although one might expect him to reference Millais’s more famous treatment of the subject in some way, Cowper’s imagination conjures a very different scene. Lorenzo walks across a sunlit courtyard, whilst in the shade, Isabella works upon an embroidery, a pot of basil before her. Through an open doorway, her brothers plot Lorenzo’s demise, one brandishing a knife in his left hand. Their depiction recalls the angular figures in early drawings by Millais and Simeon Solomon. A gathering of birds atop the sloping roof is again reminiscent of Millais’s work, although the overall composition is perhaps more indebted to Byam Shaw’s illustrations of Isabella published in 1899 (see Boccaccio 105–117). Cowper’s drawing was eventually exhibited at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1900 with lines from Keats’s ‘Isabella; or the Pot of Basil’ (‘How ill she is, said he, etc’), yet it was reproduced in 1923 with a different verse from the same poem:

So said he one fair morning, and all day

His heart beat awfully against his side;

And to his heart he inwardly did pray

For power to speak. [Salaman 157]

The drawing was given by Cowper to the artist Frank Lewis Emanuel, who also provided illustrations to The Idler.

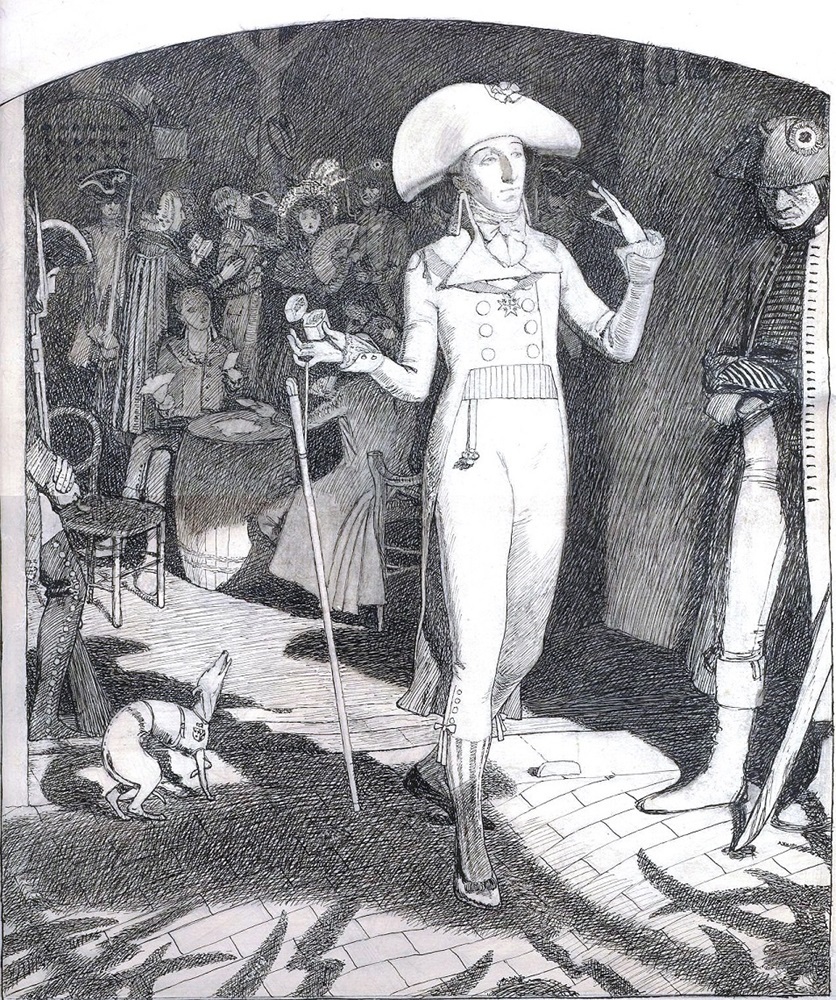

Fortitude – An Aristocrat on the Way to Execution.

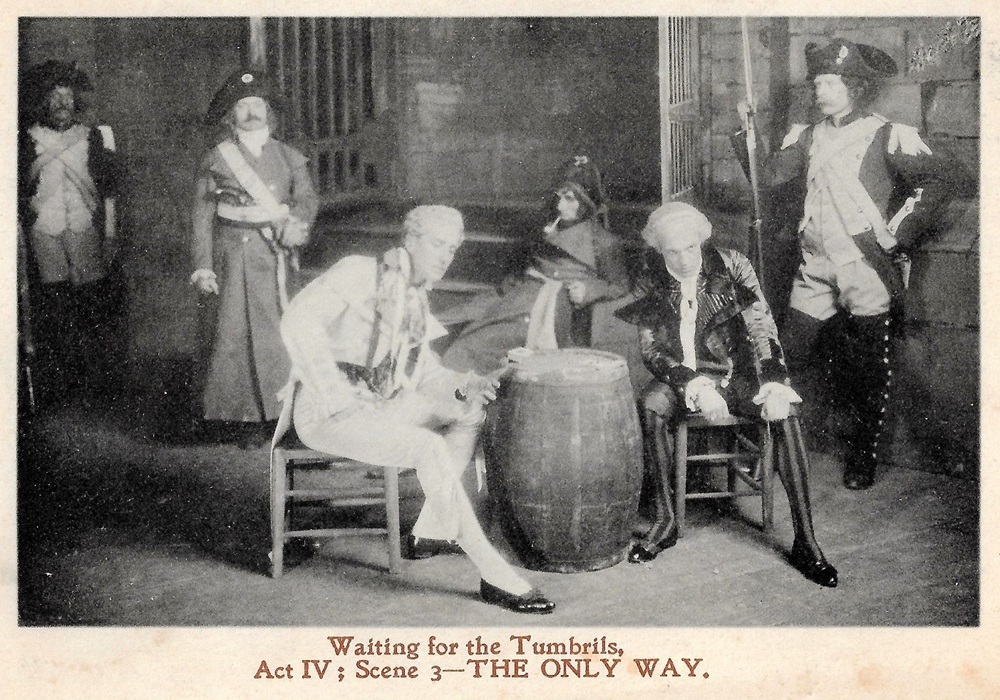

Like the works previously discussed, another of Cowper’s arched-top drawings experiments with the contrasts of light and shade, this time with a particular focus upon prominent foreground shadows. Fortitude – An Aristocrat on the Way to Execution was probably created at around the same time as Isabella and Lorenzo, although the subject depicted is from a much later historical period. It illustrates a scene from the French Revolution, although no specific literary work is cited as its source. The aristocrat emerges defiantly from the darkness of the communal cell, clasping a pinch of snuff between his fingers as he steps out towards the baying crowd, here suggested by the shadows of knives, scythes and bayonets. The retinue of fellow prisoners seem equally unperturbed by their impending fate, playing cards or taking snuff, whilst ignoring the admonitions of an abbé, prayer book in hand. Guards flank the scene, one slumped against the wall to the left, another leaning against the cell door to the right. A greyhound, bearing an aristocratic coat of arms upon its jacket, bays in the foreground. Dogs, particularly greyhounds, are a recurring theme within Cowper’s works, but are also yet another device that he has borrowed from the Pre-Raphaelite vocabulary. The obvious source for the scene of a man going defiantly to the guillotine is Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. A stage adaptation of the novel titled The Only Way, starring the actor-manager Sir John Martin-Harvey as Sidney Carton, enjoyed a long and successful run after its first performance at the Lyceum Theatre in London in 1899. Photographs of the production show a stage set similar to the cell depicted in Cowper’s drawing, including figures using an upturned barrel as a card table (Butler 50).

A postcard photograph of a scene from the stage production of The Only Way.

The success of The Only Way might have inspired Cowper to work his drawing up into an oil painting, An aristocrat answering the summons to execution – Paris, 1793, which he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1901 (Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, 1901, No. 506). A watercolour version of the subject also exists (Bonhams Lot 110). The drawing, the watercolour and the oil painting of this subject were all produced within an arch-topped format. Baroness Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel was written a few years after Cowper’s painting was exhibited - a story in which the protagonist seems to have more in common with Cowper’s aristocrat than Dickens’s Sidney Carton. The Fortitude drawing does not appear to have been published as an illustration, or separately exhibited. It was gifted by the artist to Dion Clayton Calthrop, who himself had also contributed to The Idler as both a writer and an illustrator. The two artists remained good friends, Cowper exhibiting a portrait of Calthrop as a lieutenant with the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition of 1915. In the 1990s, the unsigned drawing was sold with a misattribution to Calthrop, having previously being acquired as part of a group of Calthrop’s own drawings and watercolours (Abbott & Holder no. 231).

These early drawings by Cowper are the product of his fervour to replicate something of the mood and energy of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s graphic work. Although he continued to produce sketches and studies throughout his career, few examples have the same vitality and attention to detail as these finished illustrations (Buckle & Wilson). It is as if his detailed draughtsmanship was to become enmeshed within his painting, as this note about his technique explains:

If Mr. Cowper does all his drawing with the brush, he uses his pen, as it were, as an instrument for painting. He is not concerned with the sensitive expressiveness of the pen line, but uses it pictorially for massing his light and shade and halftones in an accumulation of infinitely delicate and scarcely perceptible crisscross strokes which produce the effect of grey washes. [Konody 31]

Following the completion of his training at the Royal Academy Schools, a six month stint in the studio of Edwin Austin Abbey and subsequent travels to Italy would strengthen Cowper’s use of colour, and would foster a new fascination for works of the Italian Renaissance. He continued to depict obscure episodes from literature and history, but in resplendent colour, his Pre-Raphaelite eye for detail continuing to manifest in his exhibited paintings and watercolours.

Bibliography

Abbott & Holder. List 327 (August 1999).

The Art Record 2, No. 43 (8 March 1902).

Boccaccio, Giovanni. Tales from Boccaccio done into English by Joseph Jacobs. London: George Allen, 1899.

Bonhams, Fine British & Continental Watercolours & Drawings (7 March 2006).

Buckle, Scott Thomas & Wilson, Neil. Frank Cadogan Cowper & Arthur Gaskin. Hove: Campbell Wilson, 2004.

Butler, Nicholas. John Martin-Harvey – The Biography of an Actor-Manager. Wivenhoe: Nicholas Butler, 1997.

Fredeman, William E. A Rossetti Cabinet. Stroud: Ian Hodgkins & Co. Ltd, 1991.

Hugo, Victor. Notre Dame De Paris (1831), Translation by Isabel F. Hapgood. New York: T. Y. Crowell & Co., 1888,

The Idler (1899).

Konody, P. G. ‘The Academy's New Associate. The work of Mr. F. Cadogan Cowper, A.R.A.’ The Pall Mall Magazine (January 1908).

Royal Academy Archives.

Royal Academy Exhibition Records.

Salaman, Malcolm. British Book Illustration, Yesterday and To-day. London: The Studio, Ltd., 1923.

The Studio 85, no. 358 (15 January 1923).

Created 22 February 2024