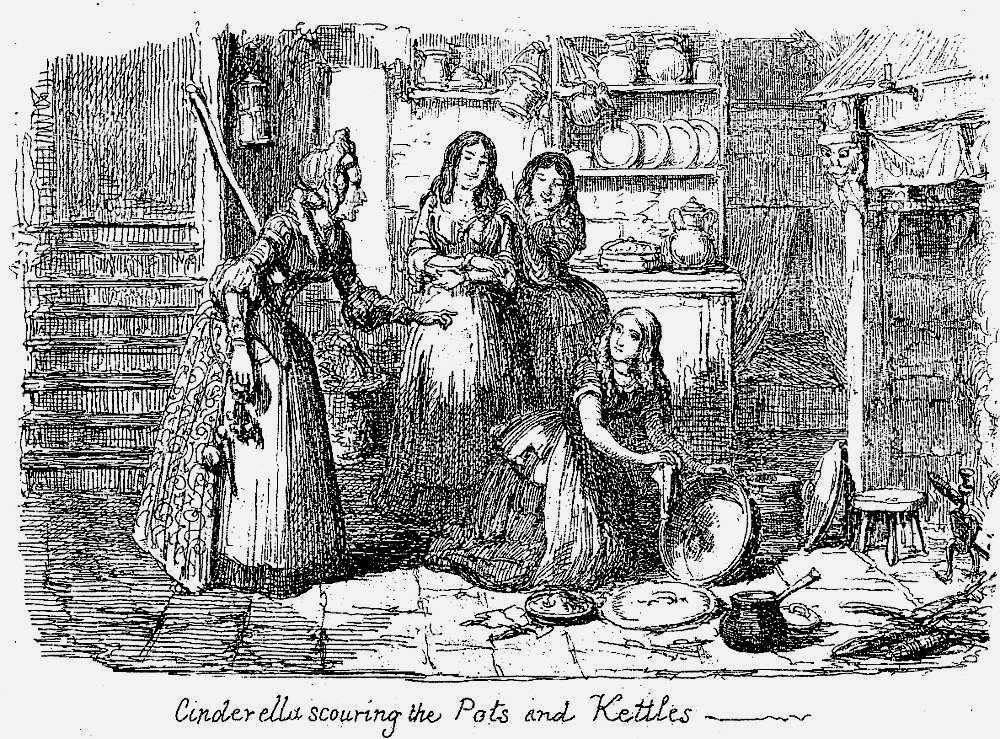

Cinderella scouring the Pots and Kettles (6.5 cm high by 9.8 cm wide, facing page 8) — the second illustration for both the single-volume edition of 1854 and for the third tale in the 1865 anthology, George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. In the second illustration, Cinderella's step-mother (left) charges her with tidying up the kitchen while she and the step-sisters go to a grand ball and banquet in honour of the coming of age of His Majesty's son, the Prince, having already served as the hair-dresser for her stepsisters. Apparently at the King's ball the Prince will choose a wife from among "the ladies in those parts" (8). Her hauteur in commanding her stepdaughter implies that Cinderella's stepmother is "proud, selfish, and extravagant, and [that] these bad qualities led her to be unjust and cruel" (6). An inveterate gambler, she has run through her own fortune and then that of her foolish, good-natured husband, who has subsequently (like John Dickens, the novelist's father) been consigned to a debtors' prison. Having had to discharge her servants in order to economize, the step-mother keeps up appearances, but uses Cinderella as a general house servant, "scolding her without any cause" (7), when she is, in fact, a member of the family.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are from the collection of the commentator.

Passage Illustrated

. . .but as the house and furniture had been settled upon her at her marriage, [the ste-mother] kept that on, and, by pinching and contriving in various ways, she managed, with a little property she had left of her own, to keep up appearances. And now began the cruel conduct towards poor Cinderella, whom she compelled to do all the rough, hard, dirty work of the kitchen and scullery, whilst she and her daughters did all the light and clean work required for the best rooms.

It is a very unpleasant thing to speak ill of ladies, but the truth must be told; and in this case we are sorry to say that the lady in question came to have a very bad temper, and behaved in a very cruel manner to Cinderella — scolding her without any cause ; and it is very painful to add that the young ladies were so influenced by their mother's example, that they also behaved very unkindly to their step-sister. — "Cinderella and The Glass Slipper, p. 7.

The Context in Perrault

No sooner were the ceremonies of the wedding over but the stepmother began to show herself in her true colors. She could not bear the good qualities of this pretty girl, and the less because they made her own daughters appear the more odious. She employed her in the meanest work of the house. She scoured the dishes, tables, etc., and cleaned madam's chamber, and those of misses, her daughters. She slept in a sorry garret, on a wretched straw bed, while her sisters slept in fine rooms, with floors all inlaid, on beds of the very newest fashion, and where they had looking glasses so large that they could see themselves at their full length from head to foot.

The poor girl bore it all patiently, and dared not tell her father, who would have scolded her; for his wife governed him entirely. When she had done her work, she used to go to the chimney corner, and sit down there in the cinders and ashes, which caused her to be called Cinderwench. Only the younger sister, who was not so rude and uncivil as the older one, called her Cinderella. However, Cinderella, notwithstanding her coarse apparel, was a hundred times more beautiful than her sisters, although they were always dressed very richly. — Chales Perrault, "Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper."

Commentary

The quaint face on the fireplace pillar reminds the reader that this is another view of the kitchen described in frontispiece. Here, we are literally "below stairs" as the staircase behind the elaborately dressed step-mother suggests. Behind the step-sisters is the dresser with its platters and vessels.Since the sisters are wearing their hair down in this panel, but up in an elaborate, eighteenth-century manner (including feathers, suggestive of the vanity) reminiscent of the styles of the Court of Versailles in Cinderella helping her Sisters to Dress for the Royal Ball (also facing page 8), we may assume that the scene in the scullery precedes that in the boudoir. Cinderella pauses in her scouring of a large serving-platter to listen to her step-mother, whose pointing with her upstage (left) hand may suggest that she is left-handed, but more likely implies that we are seeing the story enacted, as in a stage production. In the right foreground is the little stool on which Cinderella will be sitting when visited by her alternate mother, the dwarf-fairy, after the other members of the family leave for the palace. Although Cruikshank had formerly, as with the rather slatternly Nancy in Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, not been much of a hand at depicting feminine beauty, these three young women are not unattractive in their faces, figures, hair, or dress. Cinderella, very much the protagonist of both the text and narrative-pictorial sequence, appears prominently in all frames, but one: The Herald's proclaiming the Prince's wish, that all the Single Ladies should try on the Glass Slipper!.

The situation in which the clever, industrious, long-suffering Cinderella finds herself after her father's incarceration superficially resembles that of twelve-year-old Charles Dickens when his father was arrested for debt and consigned to the Marshalsea. However, the situations of the fictional and historical characters are somewhat different in that, although working during the week at Warren's Blacking, Hungerford Stairs, he spent weekends with his family. He was, moreover, supported emotionally by his parents and siblings. The other point to note is that only John Forster among the members of Dickens' circle knew about the blacking factory episode in Dickens's childhood, so that Cruikshank probably have had no idea that he was drawing a parallel between his protagonist and the novelist. One presumes that Cruikshank wished to find a plausible reason for keeping Cinderella's father out of the way without making Cinderella an orphan, and allowing for the possible release of her father when his daughter marries the Prince and can negotiate with his creditors. The situation is hardly anachronistic, however, as in eighteenth-century England (the era that the women's fashions imply) large numbers of debtors were incarcerated; for example, in 1774, although the population of Great Britain stood at six million, and there were just over 4,000 prisoners in gaols in the United Kingdom, fully half of all prisoners were insolvent debtors.

Related Materials

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1853)

- Editor's Note on "Frauds on the Fairies"

- Defending the Imagination: Charles Dickens, Children's Literature, and the Fairy Tale Wars

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- Fairy Tales: Surviving the Evangelical Attack

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas; Michael Slater and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

British Library. "George Cruikshank's Fairy Library." Romantics and Victorians. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/george-cruikshanks-fairy-library

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. Cinderella and The Glass Slipper. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. The third volume in George Cruikshank's Fairy Library. London: David Bogue, 1854. (Price one shilling) 10 etchings on 6 tipped-in pages, including frontispiece.

Cruikshank, George. George Cruikshank's Fairy Library: "Hop-O'-My-Thumb," "Jack and the Bean-Stalk," "Cinderella," "Puss in Boots". London: George Bell, 1865.

Guildhall Library blog. "A Gem from Guildhall Library's Shelves: George Cruikshank's Fairy Library by George Cruikshank published by Routledge in London (c. 1870)." 8 August 2014. https://guildhalllibrarynewsletter.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/a-gem-from-guildhall-librarys-shelves-george-cruikshanks-fairy-library-by-george-cruikshank-published-by-routledge-in-london-c1870/

Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University. "George Cruikshank." http://library.tulane.edu/exhibits/exhibits/show/fairy_tales/george_cruikshank

Hubert, Judd D. "George Cruikshank's Graphic and Textual Reactions to Mother Goose." Marvels & Tales, Volume 25, Number 2, 2011 (pp. 286-297). Project Muse. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/462736/pdf

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Perrault, Charles. "Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper." Fairy Tales and Other Traditional Stories. Lit2Go. http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/68/fairy-tales-and-other-traditional-stories/5089/jack-and-the-bean-stalk/

Vogler, Richard, The Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 29 June 2017