The Chief Characters of Oliver Twist Except Fagin Realised: 1837-1910

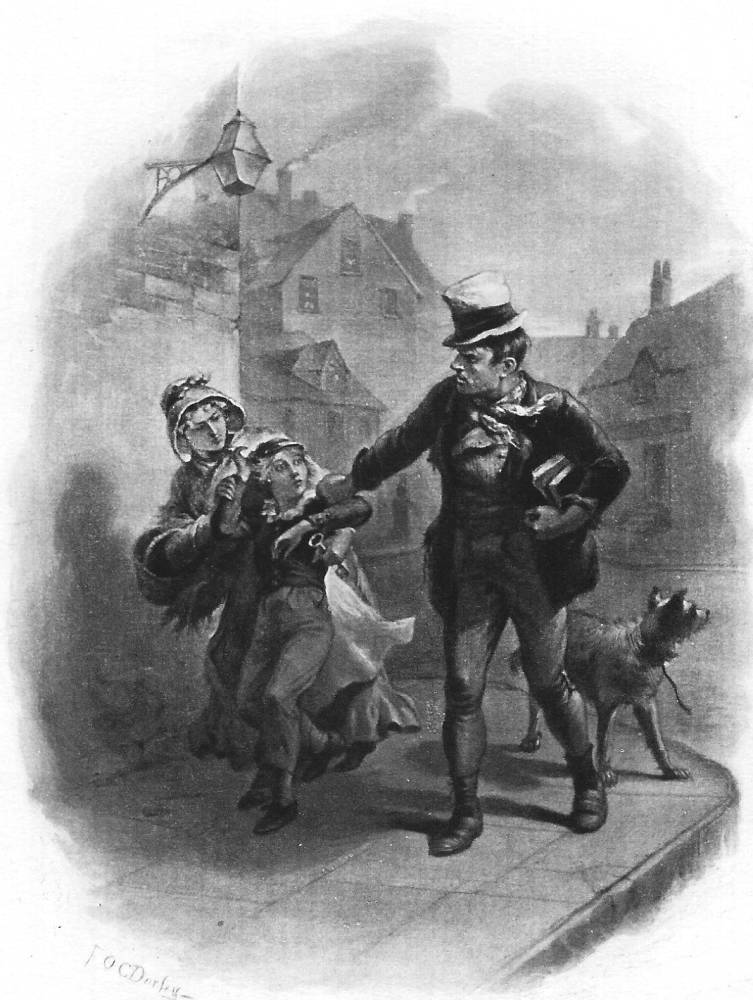

Right: American illustrator's Darley's photogravure in which Bill Sikes has just re-captured Oliver: Sikes, Nancy, and Oliver Twist (1888).

In his triple portrait of Oliver Twist, Bill Sikes, and Nancy for his Character Sketches from Dickens (1888) Felix Octavius Carr Darley uses the juxtaposition of these well-known characters to recall for readers familiar with George Cruikshank's original serial illustrations for Oliver Twist the criminal gang's re-apprehension of Oliver and through their poses and expressions to comment upon the nature of the characters themselves: timid Oliver, eager to please; devoted yet terrified Nancy; and the brutal, ruthless bully, Bill Sikes, whom Dickens first describes in Chapter 13, accompanied by Bull's-Eye:

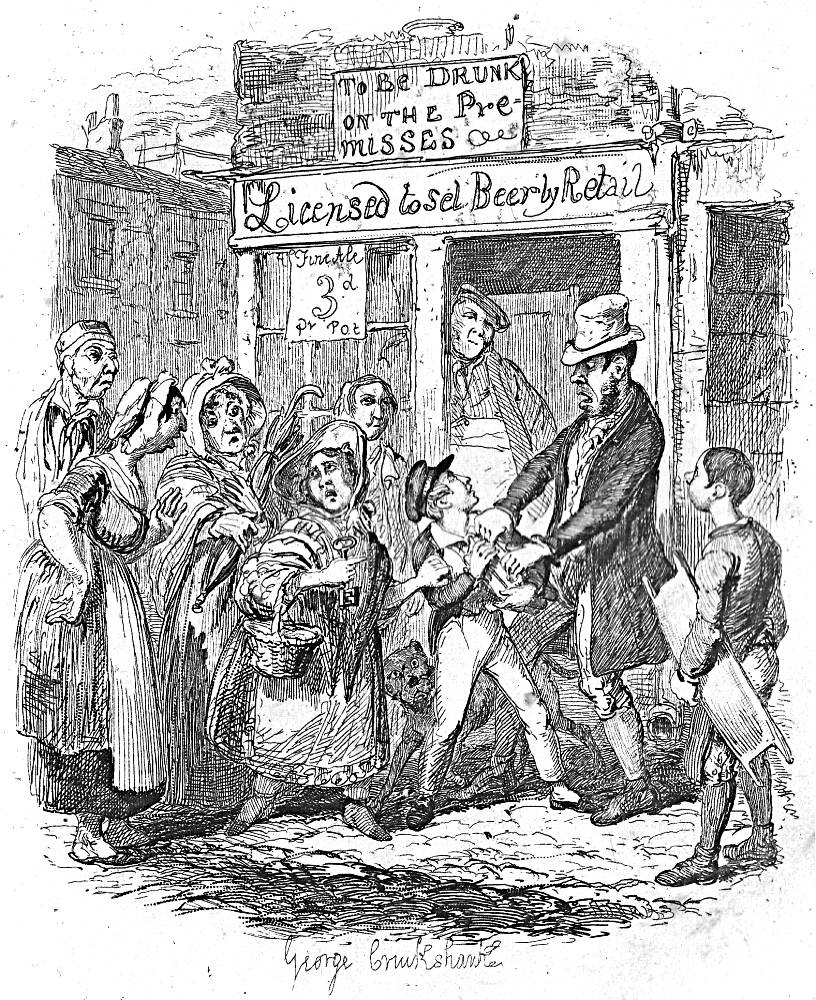

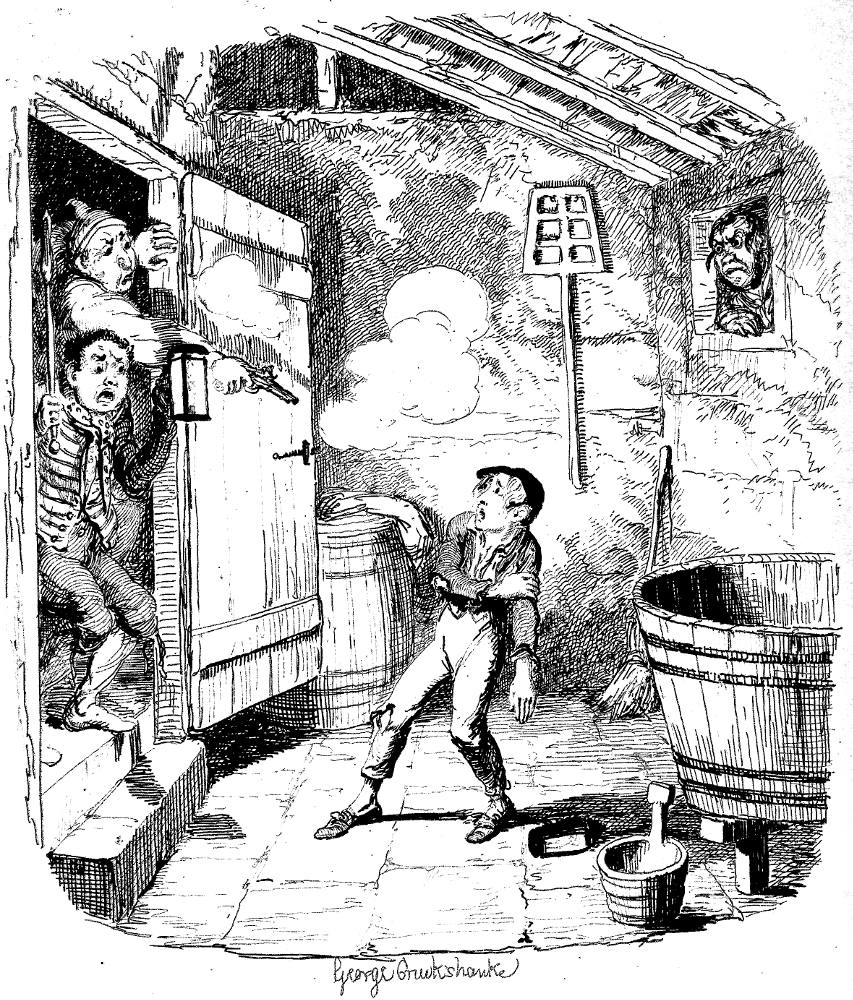

Left: Cruikshank's scene in which Bill Sikes re-captures Oliver after his time with Mr. Brownlow, the ironically entitled Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends in Chapter 15, "Showing How Very Fond of Oliver Twist, The Merry Old Jew and Miss Nancy Were" (Part 7, September 1837).

The man who growled out these words, was a stoutly-built fellow of about five-and-thirty, in a black velveteen coat, very soiled drab breeches, lace-up half boots, and grey cotton stockings which inclosed a bulky pair of legs, with large swelling calves; — the kind of legs, which in such costume, always look in an unfinished and incomplete state without a set of fetters to garnish them. He had a brown hat on his head, and a dirty belcher handkerchief round his neck: with the long frayed ends of which he smeared the beer from his face as he spoke. He disclosed, when he had done so, a broad heavy countenance with a beard of three days’ growth, and two scowling eyes; one of which displayed various parti-coloured symptoms of having been recently damaged by a blow.

"Come in, d'ye hear?" growled this engaging ruffian.

A white shaggy dog, with his face scratched and torn in twenty different places, skulked into the room. [Chapter XIII, "Some New Acquaintances are Introduced to the Intelligent Reader, Connected With Whom Various Pleasant Matters Are Related, Appertaining to this History," p. 141-142 in the Household Edition, vol. I]

Darley uses the juxtaposition of these three well-known characters to recall for those readers familiar with Oliver Twist the criminal gang's reapprehension of Oliver. Through their poses and expressions Darley comments upon the nature of the characters themselves: timid yet indignant Oliver; Nancy, Sikes's devoted confederate in crime; and the brutal, ruthless bully, Bill Sikes. The illustrations by James Mahoney in the Household Edition and by Harry Furniss in the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1871 and 1910 respectively) are also realistic responses to Cruikshank's originals, but it may be that Darley's study is as much his reaction to the dual characterization of his countryman, Sol Eytinge, Junior, the sole illustrator of the 1867 Diamond Edition, as it is to Cruikshank's originals. Certainly Darley renders Nancy an active accomplice in the boy's abduction, and therefore unworthy of the kind of sympathy with which the reader of Eytinge's Diamond Edition wood-engraving might have responded.

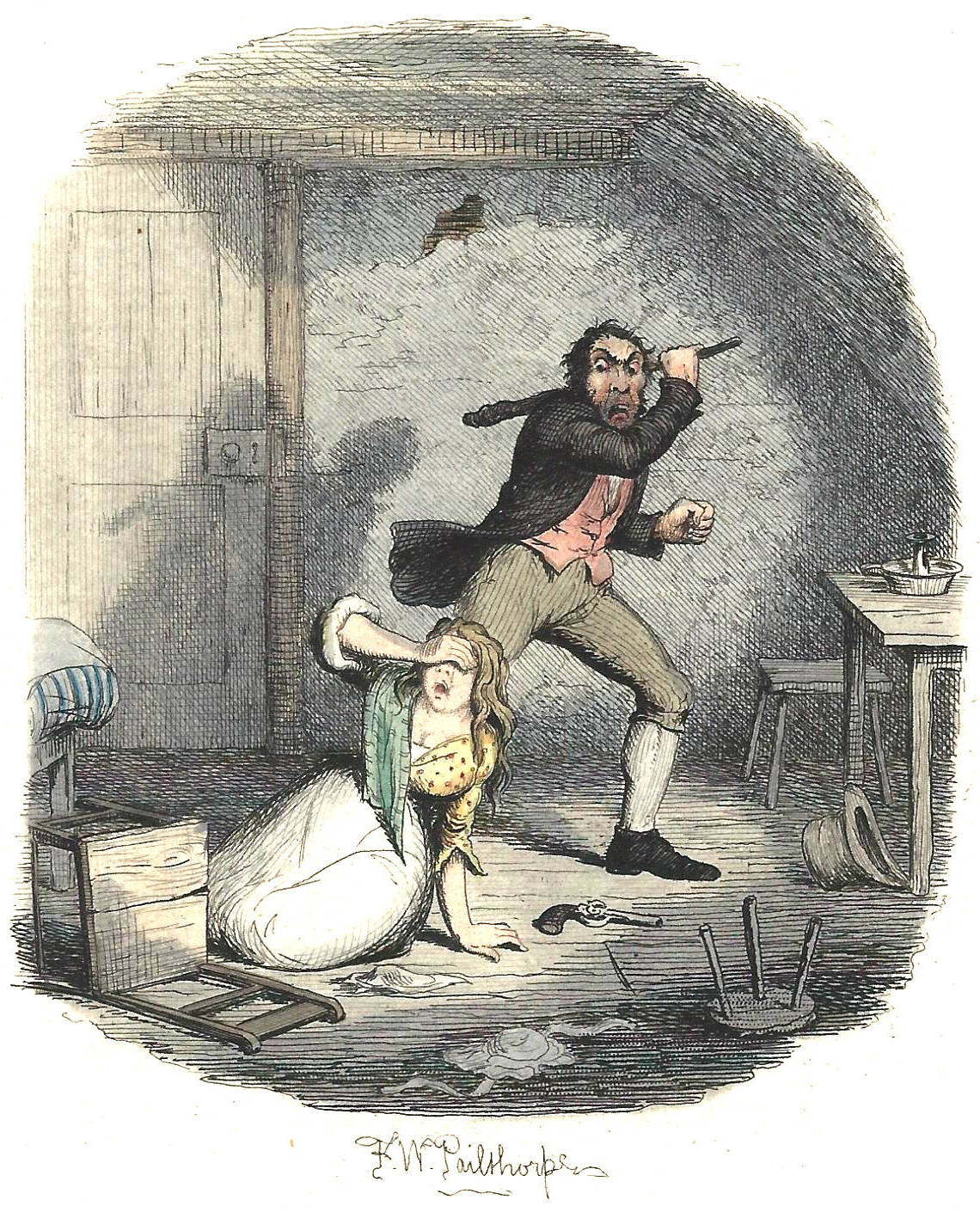

Right: British illustrator F. W. Pailthorpe's hand-tinted engraving in which Bill Sikes brutally murders Nancy: A Foul Deed (1886).

Although Darley may not have seen Frederic W. Pailthorpe's chilling and sensational A foul deed (1886), Darley was well aware of Sikes's brutal murder of Nancy. The scene is one of the story's most sensational: Sikes turns on the woman who loves him when he suspects that she has impeached upon him to the authorities. Unlike Cruikshank, Darley possessed a complete knowledge of the novel's plot that the original serial illustrator would not have had because he had only the serial instalments issued up to September 1837 to work with. Darley's task, like that of all the other post-Cruikshank illustrators, is visually to provide suggestions of Sikes's stern and brutal nature in advance of the murder in order to make Sikes's bludgeoning to death his common-law wife and quondam assistant both plausible and horrific.

Left: Cruikshank's somewhat humorous depiction of Sikes "framed" in the attempted robbery of the house at Chertsey: The Burglary (Part 10, January 1838).

Although Dickens's illustrator for the Bentley's serial run of Oliver Twist depicts the housebreaker Bill Sikes as the sordid, lower-class villain out of contemporary melodrama, the determined figure whom Darley describes is once again much moreof an individual (despite his caricatural long face and white top hat drawn from the Cruikshank series) than a type. In the chapter 22 illustration which depicts Oliver's being surprised and shot at almost as soon as he has entered to house that Sikes is attempting to rob, The Burglary, Cruikshank injects the notorious housebreaker into the scene in a framed portrait: Sikes, unable to act, watches the unfolding drama with interest and some frustration. Anthony Burton in "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction" in George Cruikshank: A Revaluation notes how throughout the sequence the artist employs doors and windows as "potent symbols of exclusion and inclusion" (127), with Sikes obviously excluded from the action here, but Oliver wounded: "the door opens on him and emits a puff of smoke and a bullet" (127).

Above: Kyd's (Clayton J. Clarke's) turn-of-the-century coloured lithographs bespeak a certain fascination with the uncouth, atavistic villain of Dickens's Newgate novel: Bill Sikes, from the Player's Cigarette Card series.

Effectively rendered, Cruikshank's ruffian is unshaven, unkempt, and full-faced — but the small window through which he peers would prevent him from firing his own weapon on the two servants, let alone haul Oliver out if harm's way by the collar in the text on the page facing the steel-engraving. Selecting an equally dramatic moment in the story, Darley depicts the brutal Sikes in action, rather than as a static figure, whereas in the 1867 Diamond Edition, Sol Eytinge in Nancy and Bill Sikes (1867) captures the disreputable couple's desperation and despondency. A youthful but haggard Nancy with bedraggled hair is refined by her gesture of deep concern for her rough companion, whose face and hands place him lower down the evolutionary scale. In the particular moment in the action that Eytinge captures, he plays the contrasting figures off against one another to reveal their natures, complementing Dickens's description of them in the facing page. Neither is shown in their former youthful vigour and health:

Lef: Sol Eytinge's dual character study contextless depiction of Sikes the housebreaker armed with a cudgel, which is an extension of his character: Bill Sikes (1867).

The room in which Mr. Sikes propounded this question, was not one of those he had tenanted, previous to the Chertsey expedition, although it was in the same quarter of the town, and was situated at no great distance from his former lodgings. It was not, in appearance, so desirable a habitation as his old quarters: being a mean and badly-furnished apartment, of very limited size; lighted only by one small window in the shelving roof, and abutting on a close and dirty lane. Nor were there wanting other indications of the good gentleman's having gone down in the world of late: for a great scarcity of furniture, and total absence of comfort, together with the disappearance of all such small moveables as spare clothes and linen, bespoke a state of extreme poverty; while the meagre and attenuated condition of Mr. Sikes himself would have fully confirmed these symptoms, if they had stood in any need of corroboration.

Right: Kyd's sympathetic portrait of Sikes's ill-kempt doxy: Nancy (c. 1910).

The housebreaker was lying on the bed, wrapped in his white great-coat, by way of dressing-gown, and displaying a set of features in no degree improved by the cadaverous hue of illness, and the addition of a soiled nightcap, and a stiff, black beard of a week's growth. The dog sat at the bedside: now eyeing his master with a wistful look, and now pricking his ears, and uttering a low growl as some noise in the street, or in the lower part of the house, attracted his attention. Seated by the window, busily engaged in patching an old waistcoat which formed a portion of the robber's ordinary dress, was a female: so pale and reduced with watching and privation, that there would have been considerable difficulty in recognising her as the same Nancy who has already figured in this tale, but for the voice in which she replied to Mr. Sikes's question. [Chapter XXXIX, "Introduces Some Respectable Characters with whom the Reader is Already Acquainted. . . ," pp. 119-120 in the Household Edition, vol. II]

Left: Furniss's contextless depiction of Sikes the housebreaker armed with a cudgel, which is an extension of his character: Bill Sikes 1910).

Darley would not of course have had the benefit of studying Harry Furniss's economical character portrait of the East End housebreaker (left), Bill Sikes (1910). However, he would undoubtedly have consulted the earlier Cruikshank engravings (readily available through American piracies), and the more recent wood-engravings by James Mahoney for the British Household Edition (1871). Whereas Mahoney's Sixties style is as realistic as Darley's, his drawings of the criminal couple lack Darley's dynamism, depth, and finish. Rejecting Cruikshank's caricatural manner, Darley has replaced Cruikshank's seedy and somewhat cartoonish crowd of bystanders outside the Regency beer shop with an atmospheric backdrop suggestive of early evening (as indicated by the gas-lamp which illuminates Nancy) in the neighbourhood of Smithfield. As in the text, Nancy's large street-door key and the boy's confiscated books are prominent — but no one is near to come to Oliver's rescue, whereas in Cruikshank's version, Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends the presence of so many curious and sympathetic bystanders leads the viewer to expect that Oliver may yet escape Sikes's grasp. Whereas Cruikshank's Nancy (readily identifiable by her basket and key) is short, dumpy, and unattractive, Darley's more modelled heroine is youthful, slender, and vigorous as she firmly restrains the frightened boy. And Darley utilizes as binary opposites Oliver's expensive Regency clothing (a revenant of Mr. Brownlow's care) and the thug's soiled togs. Brownlow's books, the key, and the nearby street-lamp, although not represented as anything but what they are, reveal that Darley had scrupulously re-read Dickens's text, and thought through the theatrical properties, poses, and juxtapositions of his characters, as well as the nocturnal setting in Smithfield. A nice touch is Darley's including Sikes's vigilant dog — a far cry from the slight, short-coated cur in the Cruikshank plates — a dingy off-white Bull's-Eye, scanning the deserted street, as if he is standing guard for the malefactors to ensure that they are not apprehended — rendering Sikes's later attempting to murder the dog all the more ironic.

Other Relevant Illustrations of Bill Sikes and Nancy (1846-1910)

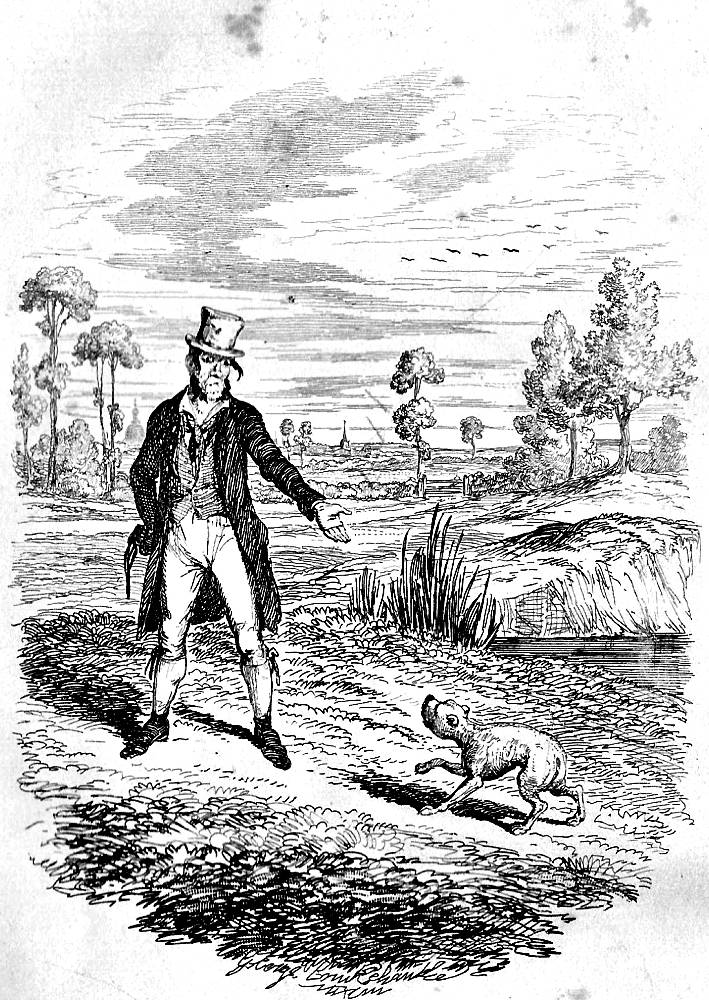

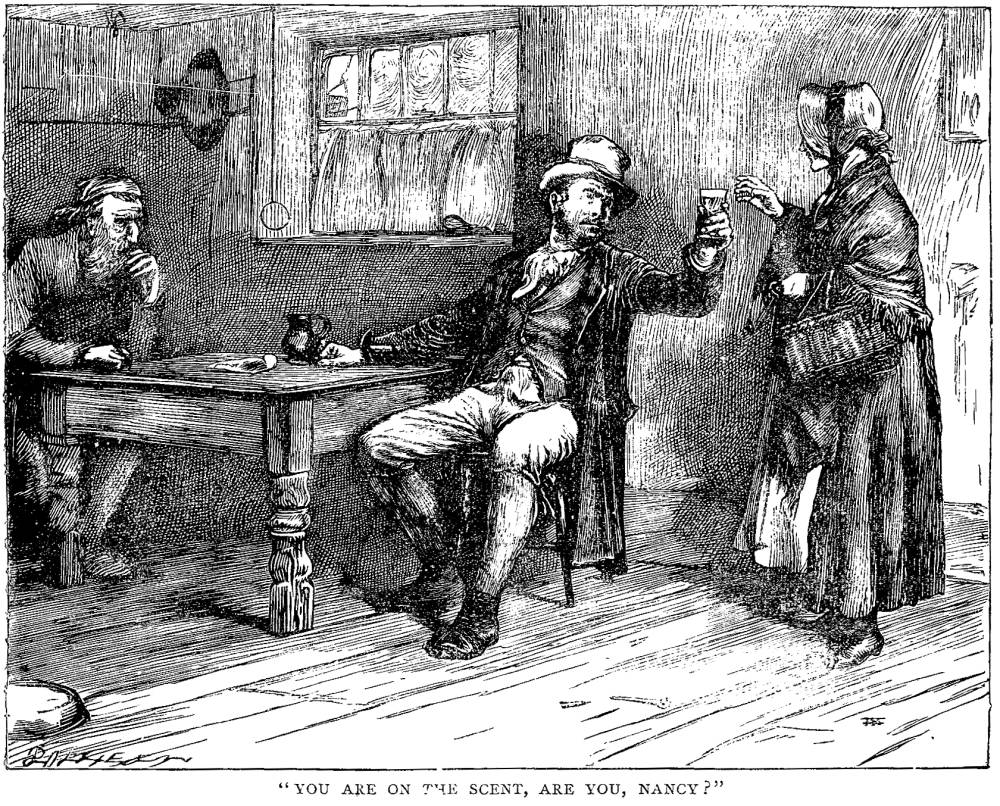

Left: Furniss's Oliver in the Grip of Sikes (1910). Centre: Cruikshank's Sikes attempting to destroy his dog (1846). Right: Mahoney's Household Edition illustration (1871) "You are on the scent, are you, Nancy?". [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Material

- Oliver Twist Illustrated, 1837-1910

- George Cruikshank's Serial Illustrations for Dickens's Adventures of Oliver Twist (February 1837 through April 1839)

- Versions of the Botched Burglary in Oliver Twist, Ch. 22

- Early dramatic adaptations of Oliver Twist (1838-1842)

- Alternative Dickens: cartoon based on Cruikshank in Oliver Twist

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Bolton, Theodore. The Book Illustrations of Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1951). Worcester, Mass: American Antiquarian Society, 1952.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974. Pp. 93-128.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

_______. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865. 2 vols.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_______. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

Grego, Joseph (intro). Cruikshank's Water Colours. [27 Oliver Twist illustrations, including the wrapper and the 13-vignette title-page produced for F. W. Cosens; 20 plates for William Harrison Ainsworth's The Miser's Daughter: A Tale of the Year 1774; 20 plates plus the proofcover the work for W. H. Maxwell's History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798 and Emmetts Insurrection in 1803]. London: A & C Black, 1903. OT = pp. 1-106]. Book in the Rare Book Collection of the University of Toronto.

Pailthorpe, Frederic W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Created 15 November 2021 Last updated 5 December 2021