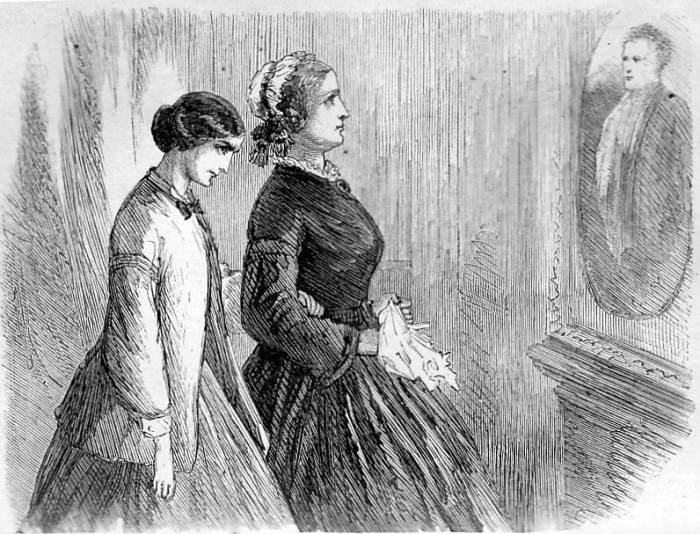

Mrs. Steerforth and Rosa Dartle, the eleventh full-page illustration for the volume by Sol Eytinge, Jr. 7.6 cm high by 10 cm wide (4 by 3 inches), vignetted. Charles Dickens's The Personal History of David Copperfield (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867), facing page 243. [Mouse over the text for links. Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Commentary

Whereas Phiz depicted Mrs. Steerforth and her misanthropic companion, Rosa Dartle, in company with Dan'l Peggotty and David Copperfield in Mr. Peggotty and Mrs. Steerforth, Eytinge isolates the pair in front of a portrait of the son of the house, implying their utter devotion to the beautiful image. That Rosa's attitude towards the sociopathic youth is more complex than his mother's Eytinge makes clear by her intense gaze, slightly lowered head, and hardened expression.

Phiz had no need of interpolating portraits on the walls of the old brick mansion at the fashionable north London suburb of Highgate (then just a village adjacent to Hampstead) when he depicted interior scenes in the Steerforth home, so that it is logical that Eytinge, building on Phiz's work, should have depicted Steerforth's mother and her companion studying or responding to a portrait of James Steerforth in the eleventh illustration. Although David Copperfield visits the home four times over the course of the story, beginning in Chapter 20 ("Steerforth's Home"), Eytinge has juxtaposed the picture with David's second visit, in Chapter 29, "I Visit Steerforth at His Home, Again." During his initial visit the doting mother had proudly displayed smaller pictures of her son as a child and as a school student, and David had noted a portrait of Mrs. Steerforth in James's bedroom — and an unsettling likeness of Rosa Dartle in the room assigned to himself:

Steerforth's room was next to mine, and I went in to look at it. It was a picture of comfort, full of easy-chairs, cushions, and footstools, worked by his mother's hand, and with no sort of thing omitted that could help to render it complete. Finally, her handsome features looked down on her darling from a portrait on the wall, as if it were even something to her than her likeness should watch him while he slept.

I found the fire burning clear enough in my room by this time, and the curtains drawn before the windows and round the bed, giving it a very snug appearance. I sat down in a great chair upon the hearth to meditate on my happiness, and had enjoyed the contemplation of it for some time, when I found a likeness of Miss Dartle looking eagerly at me from above the chimney-piece.

It was a startling likeness, and necessarily had a startling look. . . . . I wondered peevishly why they couldn't put her anywhere else instead of quartering her on me. [Chapter XX, "Steerforth's Home," 168]

The term "quartering" here suggests that David feels that an official entity has violated his personal space, just as Canadians resented American troops being "quartered" in their homes when their country was occupied by foreign troops during the War of 1812 — American colonists suffered a similar intrusion when, during the Revolutionary War, British forces sometimes used private homes for billets. However, the salient features of these "portrait" passages are David's enjoyment of the superficialities of upper-middle-class domesticity ("picture of comfort," "render it complete") and his seduction by elegant surfaces such as Mrs. Steerforth's and her son's "handsome features." He finds, in contrast, Rosa's visage (whether represented or in the real) "unsettling" because her searching gaze penetrates beneath the smooth, comfortable veneer of the Highgate establishment, her scar a potent signifier of Steerforth's true character.

In Chapter 19, "I Visit Steerforth at His Home Again," David finds Rosa in person as unsettling as her portrait, but sees in the Steerforths "two such shades of the same nature" (244) as if they are companion portraits rather than people. Although David attends very much to the expressions of both ladies, in this chapter (although it would certainly be characteristic) there is no scene such as Eytinge's eleventh illustration describes. However, in Chapter 56, after Steerforth's death in the preceding chapter, "Tempest," David in the drawing-room notes that "His picture, as a boy, was there" (["The New Wound, and the Old," 450). This would likely bve the portrait that Eytinge has depicted in an imagined moment that must, since Mrs. Steerforth is not in mourning, occur after Steerforth has gone abroad with Em'ly but prior to David's reporting his drowning. When the little parlour maid ushers David into Mrs. Steerforth's presence, he learns that, now an invalid, Mrs. Steerforth has chosen to occupy her son's room. He recognizes that her lack of mobility is a mere excuse for her to occupy her son's personal space. She is still, despite her infirmity and advancing age, "handsome" and "so like" (451) her son in the face. After her son's corpse has been laid out in Mrs. Steerforth's old room, David notes that she has finally become a work of art, for "she lay like a statue" (452). Our last glimpse of her in her garden at Highgate, in Chapter 64, is of an "old pride and beauty, feebly contending with a querulous, imbecile, fretful wandering of mind" (493), conflicting surface and reality still.

The narrator's dwelling on the superficial resemblance between mother and son reaches its highest pitch in Chapter 32, "The Beginning of a Long Journey," when David visits the Highgate house a third time, accompanied on this occasion by Dan'l Peggotty in search of news of his niece, Em'ly:

I thought her more like him than ever I had thought of her; and I felt, rather than saw, that the resemblance was not lost on my companion. [263]

Mr. Peggotty in the memorable and eloquent appeal for her assistance underscores that he is "looking at the likeness of the face. . . that has looked at me, in my home, at my fire-side, in my boat — wheer not? — smiling and friendly, when it was so treacherous" (264). Denying the legitimacy of the common man's tender feelings, the strong-willed, haughty mother is unmoved and unsoftened by the uncle's emotional appeal for her assistance. David and Dan'l Peggotty leave her "a picture of a noble presence and handsome face" (265). Nowhere in this chapter does Dickens create a scene such as Eytinge has constructed, with the two women before the iconic, dazzling images of James Steerforth, but clearly the moment pertains to the mother-son relationship as it exists at that point.

The textual reiteration of the likenesses in the Highgate house suggests the Steerforths' but also David's near-obsession with the cultivation of a beautiful image, of the proper appearance, of admirable fashion and dress, rather than a genuine appreciation of the underlying realities of character, humanistic values, and intellect. Ironically, Rosa, as we see in Eytinge's dual character study, both loves and loathes the handsome youth who had caused her facial disfigurement. Further, the illustration reveals the growing tendency in the style of the sixties to represent the idea of the story and its characters rather than an actual moment in the narrative.

Related Resources

- The Remains of the Day: Death and Dying in Victorian Illustration

- Hablot Knight Browne's forty original serial illustrations for Chapman and Hall (May 1849-November 1850)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1863)

- W. H. C. Groome's 7 lithographs for the Collins Clear-type Pocket Edition (1907)

- Fred Barnard's 62 Illustrations for the British Household Edition (1872)

- Harry Furniss's 29 lithographs for David Copperfield for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's six Player's Cigarette Card watercolours (1889)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford, New York, and Toronto: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Personal History of David Copperfield, illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Centenary Edition. London & New York: Chapman & Hall, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911 [rpt. from 1850]. 2 vols.

_______. The Personal History of David Copperfield. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. Vol. V.

Created 21 January 2011 Last modified 11 July 2022