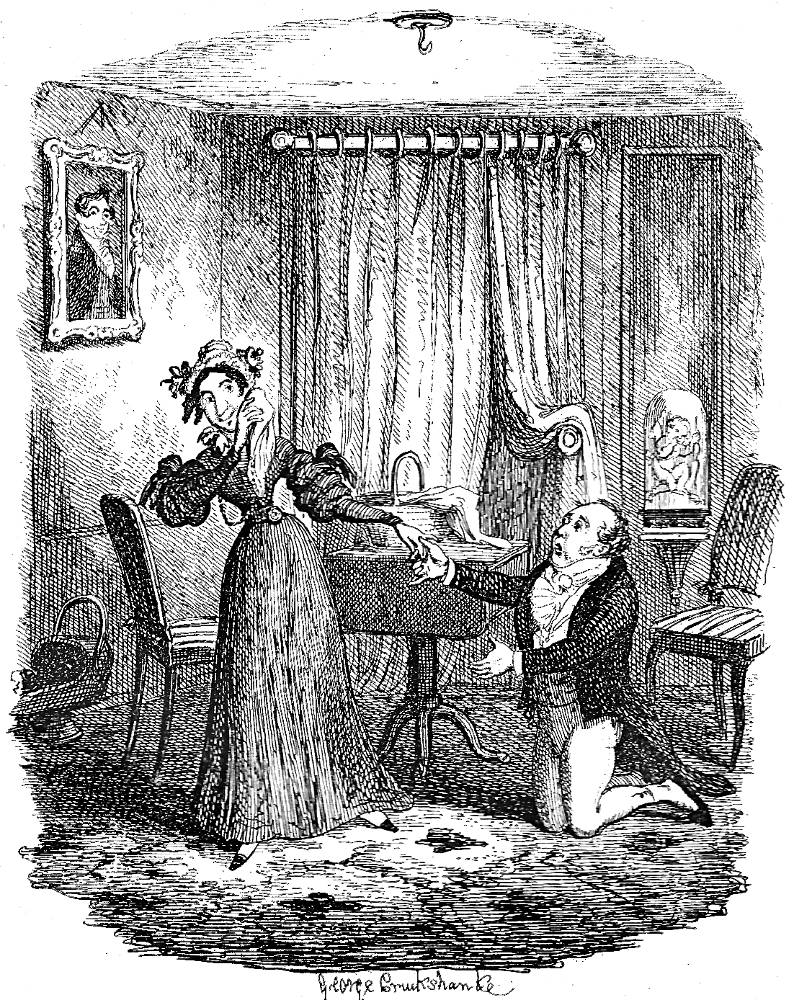

"But have he goodness to tell me in three words the contents of that note.". Drawn by A. B. Frost. Wood engraving. For Part IV, "Tales": The second part of Chapter X, "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle" — twenty-seventh illustration for Dickens's Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People, page 267. Wood-engraving; 4 ¼ by 5¼ inches (10.6 cm high by 13.2 cm wide), framed. Parsons' scheme to have Tottle redeem his debts runs into a snag.

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Bibliographical Information

The 1876 and 1877 British and American Household Editions of Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People contain a total of four illustrations for "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," two by Fred Barnard and two by A. B. Frost. This somewhat rambling narrative first appeared in the Monthly Magazine for January and February 1835, and became in 1839 the tenth chapter in "Tales." George Cruikshank provided three copper-plate engravings as illustrations for the lengthy story in the 1839 Chapman and Hall edition. Sol Eytinge, Jr., provided a single illustration for the story in the 1867 Diamond Edition (Boston: Ticknor & Fields), and Harry Furniss a lively character study of the Sheriff-Officer's Mercury in the 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition. The present illustration by A. B. Frost appears on p. 267 in the 1877 Harper and Brothers edition with the following descriptive headline: "Slightly Mistaken."

Passage Illustrated: Deferring "the pleasures of a matrimonial life"

Mr. Watkins Tottle staggered against the wall, and fixed his eyes on Timson with appalling perseverance.

"Timson," said Parsons, hurriedly brushing his hat with his left arm, "when you say 'us,' whom do you mean?"

Mr. Timson looked foolish in his turn, when he replied, "Why — Mrs. Timson that will be this day week: Miss Lillerton that is — "

"Now don’t stare at that idiot in the corner," angrily exclaimed Parsons, as the extraordinary convulsions of Watkins Tottle's countenance excited the wondering gaze of Timson, — "but have the goodness to tell me in three words the contents of that note?"

"This note," replied Timson, "is from Miss Lillerton, to whom I have been for the last five weeks regularly engaged. Her singular scruples and strange feeling on some points have hitherto prevented my bringing the engagement to that termination which I so anxiously desire. She informs me here, that she sounded Mrs. Parsons with the view of making her her confidante and go-between, that Mrs. Parsons informed this elderly gentleman, Mr. Tottle, of the circumstance, and that he, in the most kind and delicate terms, offered to assist us in any way, and even undertook to convey this note, which contains the promise I have long sought in vain — an act of kindness for which I can never be sufficiently grateful." [Part IV, "Tales," Chapter X, "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," pp. 206-7]

Commentary: Misapprehended Matrimonial Manoeuvres

As The Dickens Index suggests, in the two-part short story "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle" Dickens makes use of the ludicrous plot gambits of the early Victorian farce:

Comic account of an impoverished middle-aged bachelor's attempt, initiated and organized by his prosperous friend, Gabriel Parsons, to capture the affections of a prim, well-to-do spinster, Miss Lillerton. During the course of the story Tottle is arrested for theft [actually, debt] and taken to a sponging-house, from which he is rescued by Parsons. [p. 191]

When we last saw Parsons, he was a much younger man, but he has not materially changed from being the prematurely balding bridegroom of "And, as Fanny and the girl replaced the deal chimney-board" (258). This illustration, however, marks Tottle's first appearance in the narrative-pictorial sequence. Frost has deduced from Dickens's remarks about Tottle's "breaking two brace-buttons and a waistcoat-string in the act" (265) of dropping to his knees to propose that Tottle must be stout and middle-aged ("He was about fifty years of age;" 253). His being fat contrasts Parsons' leanness, and Frost has further developed the contrast by giving Tottle more hair, and Parsopns mutton-chop sideburns. The comfortable furnishings support Timson's solidly upper-middle-class status, which renders him a more suitable husband for the wealthy spinster than the penurious (or at least perpetually hard up) Watkins Tottle. Parsons had hoped to recoup his loans to Tottle by insuring that his old friend became Miss Lillerton's husband, and therefore, under British laws of matrimony, the administrator of her person fortune. Tottle has so badlky botched his interview weith the spinster that he has incorrectly assumed that she has accepted his proposal ("falling bump on his knees") to become her "slave," "servant," and "confidant of [her]." For her part in the mutual confusions, Miss Lillerton through Tottle's ambiguous profession of devotion mistakenly assumes that the old bachelor is acting as the Rev. Timson's go-between. Believing Tottle to be in the confidence of her friend, Mrs. Fanny Parsons, Miss Lillerton has mistakenly assumed that Tottle has agreed to be her emissary with her finbance, the Reverend Mr. Timson, to whom she has been secretly engaged for over a mointh.

Previous to the scene depicted, Tottle has obfuscated matters by describing himself obliquely as he proposes that Miss Lillerton may "become the wife of a kind and affectionate husband" (205). The lady incorrectly assumes that Mrs. Parsons has confided in Tottle about the secret engagement. Her embassy to the minister Tottle misconstrues as an acceptance of his proposal as she means to arrange the marriage ceremony right away. Dickens brilliantly manipulates the dialogue to extend the misunderstandings of both ignorant parties:

"Stay — stay," cried Watkins Tottle, still keeping a most respectful distance from the lady; "when shall we meet again?"

Oh! Mr. Tottle," replied Miss Lillerton, coquettishly, "when we are married, I can never see you too often, nor thank you too much;" and she left the room. [265]

Thus, Tottle arrives at Timson with Parsons in tow assuming that they are arranging his marriage rather than Timson's. Readers, turning the page to discover the illustration, are immediately aware that Tottle has suddenly fallen ill or drastically out of sorts as, stupefied, he slumps against the wall of Reverend Timson's apartment. Parsons, apprehending the misinterpretation, touches the minister's arm to request a clarification of the instructions. The minister seems somewhat aloof — after all, what is Parsons' role in his marriage arrangements? Despite her "sin gular scruples" (207) in her communications with Timson, Miss Lillerton has confided in Mrs. Parsons, and in the letter indicates her mistaken conclusion that her confidant has let Tottle in on the secret because he has offered and she has accep[ted his offer of assistance. Parsons, who noiw thoroughly comprehends the error that his friend has made, beats a hastey retreat with the still bewildered Tottle in tow.

Initial and Subsequent Editions of "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle" (1835-1877)

Probably because the actual name of the monthly journal in which the story first appeared in the opening months of 1835 was rather a mouthful — The British Register of Literature, Science and Belles Letters, Londoners of the 1830s simply called it The Monthly Magazine. Under the editorship of Captain J. B. Holland the small-circulation periodical could not afford to pay its contributors. Nevertheless, over the first three years of Dickens's career as a writer the literary journal enabled him, presenting himself under the pseudonym "Boz," to place before the reading public nine of his longest sketches, beginning with "A Dinner at Poplar Walk" and concluding with "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle."

As Frederic G. Kitton notes, Cruikshank had to re-engrave this illustration for the Chapman and Hall serialisation, and the subsequent 1839 anthology:

During the following year (1837) Macrone published a Second Series of the "Sketches" in one volume, uniform in size and character with its predecessors, and containing ten etchings by Cruikshank; for the second edition of this extra volume two additional illustrations were done, viz., "The Last Cab-Driver" and "May-day in the Evening." It was at this time that Dickens repurchased from Macrone the entire copyright of the "Sketches," and arranged with Chapman & Hall for a complete edition, to be issued in shilling monthly parts, octavo size, the first number appearing in November of that year. The completed work contained all the Cruikshank plates (except that entitled The Free and Easy, which, for some unexplained reason, was cancelled) and the following [twelve] new subjects: "The Parish Engine," "The Broker's Man," "Our Next-door Neighbours" [sic], "Early Coaches," "Public Dinners," "The Gin-Shop," "Making a Night of It," "The Boarding-House," "The Tuggses at Ramsgate," "The Steam Excursion," "Mrs. Joseph Porter," and "Mr. Watkins Tottle." ["George Cruikshank, p. 4]

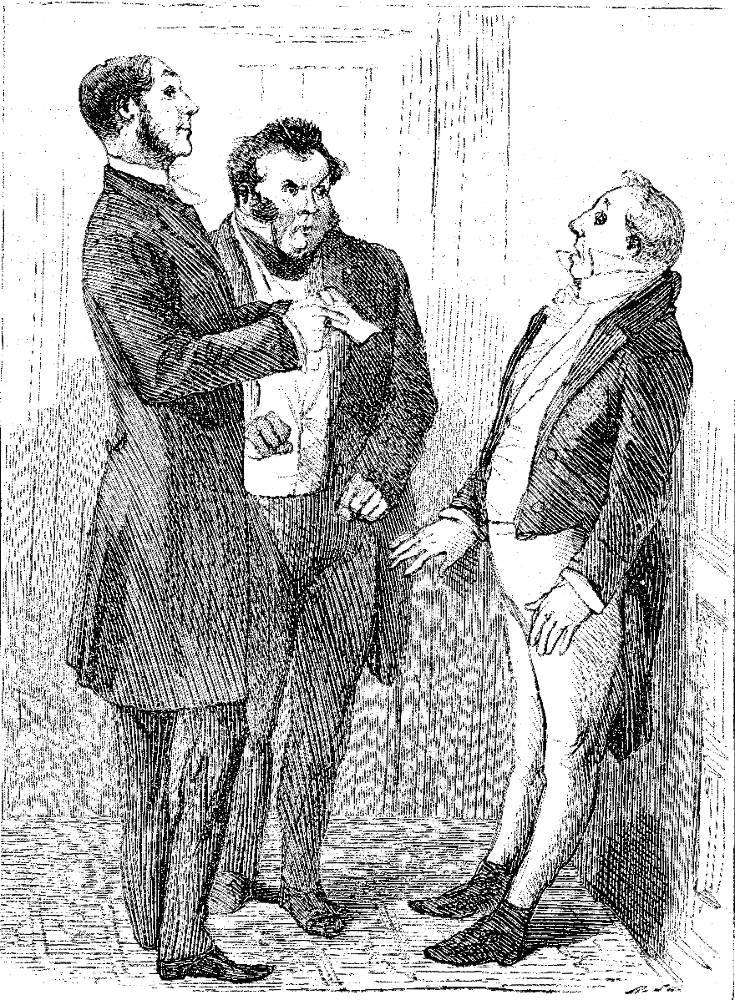

In the 1839 edition, "A Passage in the Life of Watkins Totle" was the only selection to be accompanied by three Cruikshank copper-plate engravings. No new illustrations for the story appeared when Chapman and Hall re-issued Sketches by Boz in the Library Edition (1858). The Ticknor Fields Diamond Edition, issued to coincide with Dickens's second American reading tour (1867), had only eight small-scale wood-engravings for Sketches by Boz — one of these, entitled Watkins Tottle, depicts Parsons and Tottle learning from the Rev. Timson that he has won Miss Lillerton's hand — precisely the scene that Frost has realised. However, when Chapman and Hall contracted Fred Barnard to illustrate the London sketches for the 1876 Household Edition, the slender, double-columned volume contained three large-scale wood-engraving for this story; the following year, the Harper and Brothers Household Edition volume, contained twenty-eight wood-engravings for that part of the volume involving the Sketches, two of which Frost devoted to the story.

The later illustrators of the story, using the original Cruikshank trio of copper-plate engravings as their point of departure, have focussed on the interesting but minor figure of the sheriff-officer's mercury (messenger), who in the second chapter delivers the news to Parsons that Tottle has been apprehended for debt, and on Parson's flashback to his own rather rocky courtship of Fanny. This is the only story in the 1839 Chapman and Hall anthology to receive three illustrations, and one of the few in the 1876 Household Edition to receive more than a single wood-engraving, so that both elements, the farcical marriage plot and the ridiculous superannuated bachelor's failed attempt to secure a wealthy bride, must have been very appealing to George Cruikshank, Sol Eytinge, Junior, Fred Barnard, A. B. Frost, and Harry Furniss.

Illustrations from the 1839 and Other Editions for "Watkins Tottle"

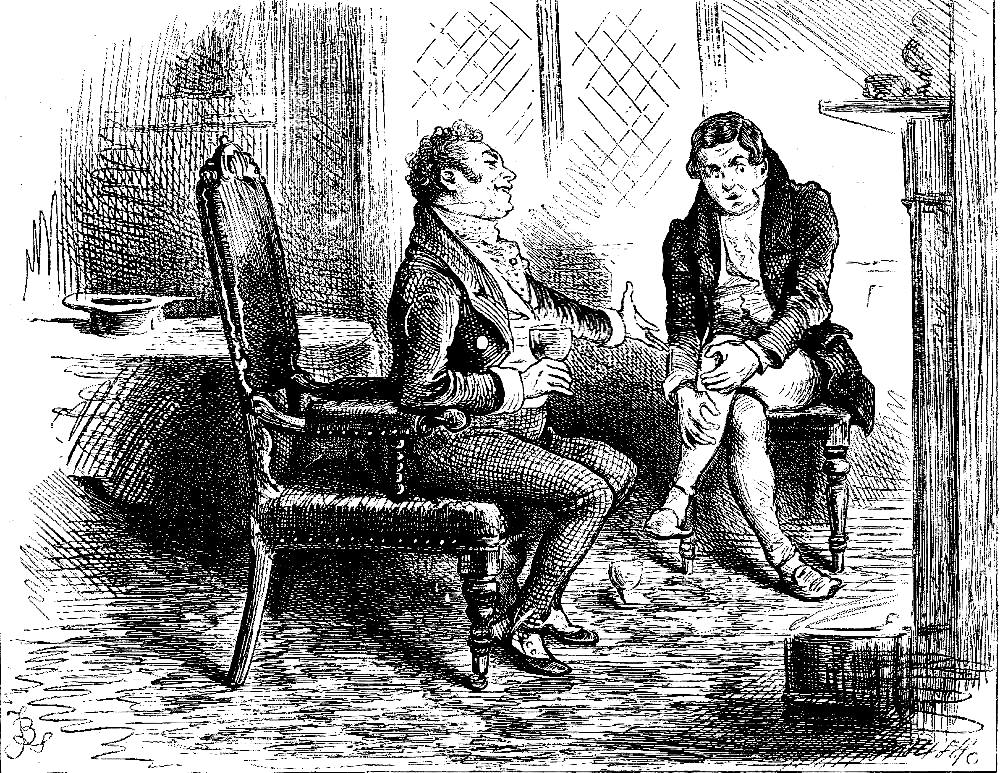

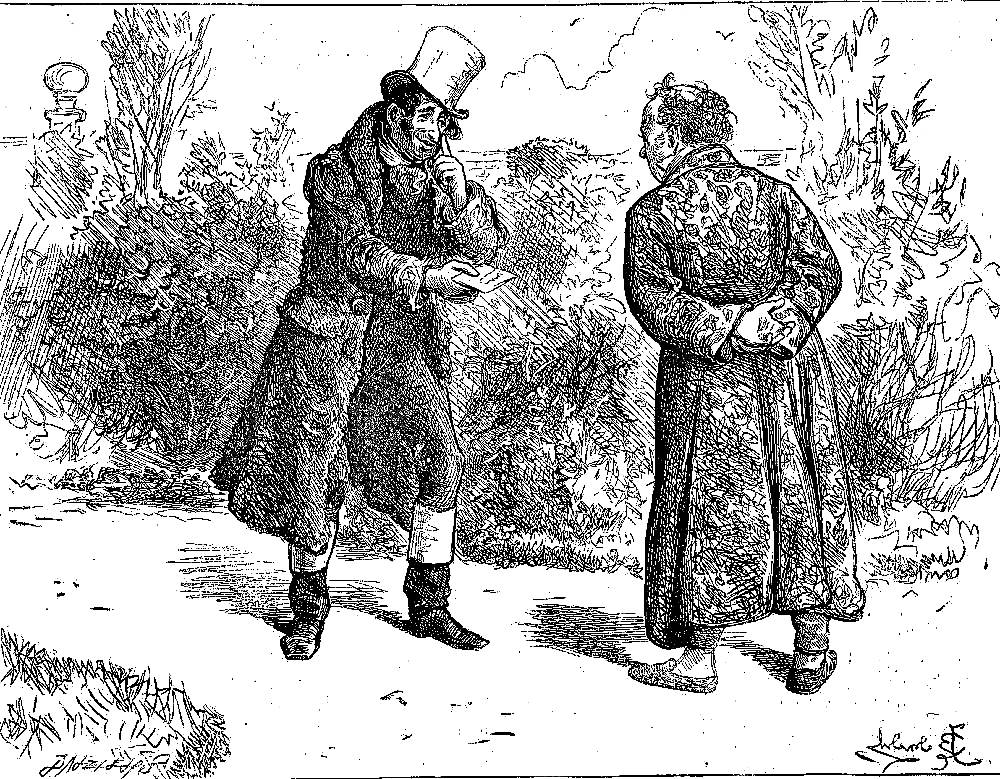

Left: Cruikshank's initial illustration for the story, introducing the timid protagonist, Watkins Tottle. Left of centre: Cruikshank's third illustration, which suggests that Tottle will be successful in his courtship of the affluent spinster, Mr. Watkins Tottle and Miss Lillerton. Right of centre: Eytinge's single illustration, featuring Tottle (right), Rev. Timson (lefty), and Parsons (centre), as they learn of Miss Lillerton's engagement to the Anglican minister, Mr. Watkins Tottle (1867). Right: Furniss's realisation of the agent of the lock-up house, The Sheriff-Officer's Mercury (1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

The Relevant Illustrations from The British Household Edition (1876)

Above: Fred Barnard's wood-engraving of the interview between Parsons and Tottle in the two-part short story, "Why," replied Mr. Watkins Tottle, evasively; for he trembled violently, and felt a sudden tingling throughout his whole frame; "Why — I should certainly — at least, I think I should like —" — to marry the wealthy spinster, Miss Lillerton.

Above: Fred Barnard's wood-engraving of the scene in which Solomon Jacobs' minion reveals that Tottle has been apprehended for debt, "I've brought this here note," replied the individual in the painted tops in a hoarse whisper; "I've brought this here note from a gen'l'm'n as come to our house this mornin'."

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z. The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. ""A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 326-55.

Dickens, Charles. "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor and Fields edition]. Pp. 465-85.

Dickens, Charles. "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 115-17.

Dickens, Charles. Part IV, "Tales," Chapter X, "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by A. B. Frost. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1877. Pp. 253-68.

Dickens, Charles. "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. I, 419-55.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. (1899). Rpt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2004.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and the Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 27 April 2019