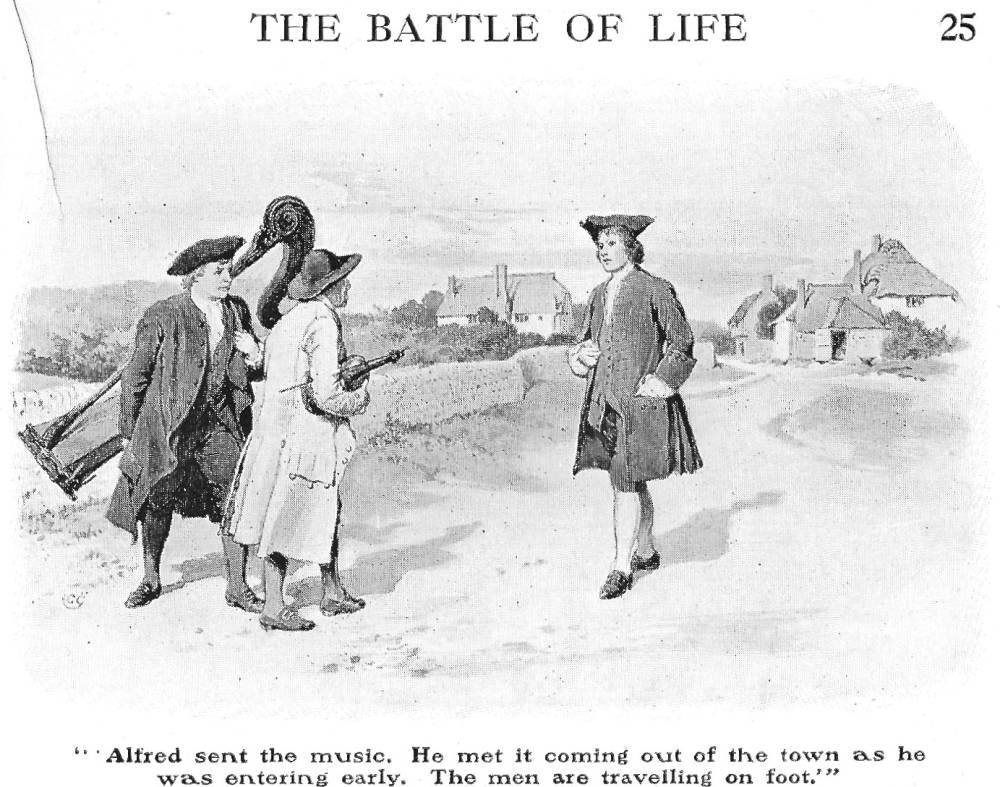

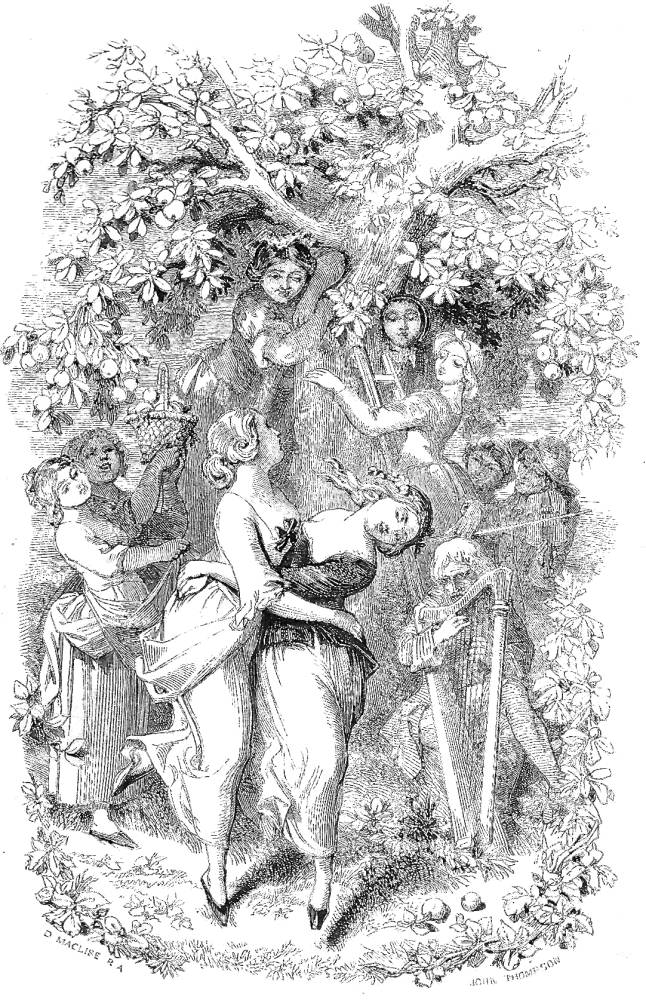

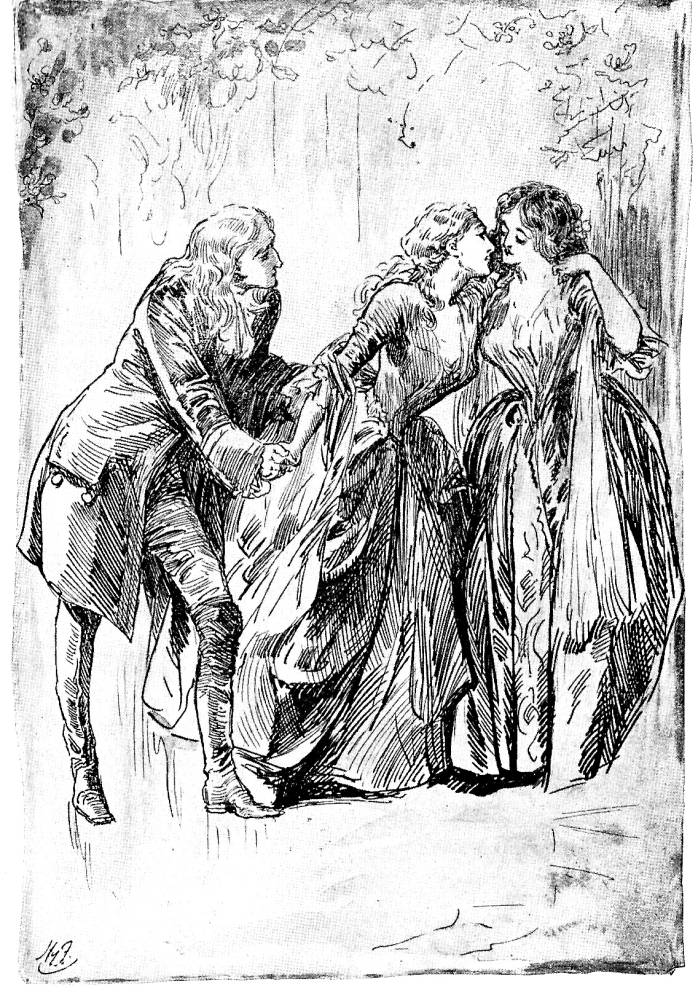

"Travelling Musicians" by Charles Green (25). 1912. 7.4 x 11.2 cm, vignetted. Dickens's The Battle of Life, Pears Centenary Edition, in which the plates often have captions that are different from the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (p. 13-14). Specifically, Travelling Musicians has a lengthy caption that is quite different from its title in the "List of Illustrations"; the textual quotation that serves as the caption for the imagined scene at the edge of the village where Alfred engages the travelling fiddler and harpist to play for Marion's birthday, is "Alfred sent the music. He met it coming out of the town as he was entering early. The men are travelling on foot" ("Part the First," p. 25, from the text on the facing page) — a picturesque backdrop of cottages comprising the slower-paced lifestyle of pre-nineteenth-century England. In the 1846 edition of the novella, there is no equivalent illustration; however, the musicians (looking much less the travelling professionals and much more the peasant practictioners) appear in Daniel Maclise's frontispiece, Grace and Marion Jeddler Dancing (see below). The Household Editions, illustrated by Fred Barnard and American E. A. Abbey, contain no picture of either the dancing sisters or the musicians. However, A. A. Dixon in the 1906 Collins' Clear-Type Press edition uses the scene of the sisters dancing in the orchard as the frontispiece, Danced in the freedom and gaiety of their hearts (see below); however, this lithograph focuses on the sisters and does not include the itinerant musicians.

Passage Illustrated

"Well! But how did you get the music?" asked the Doctor. "Poultry-stealers, of course! Where did the minstrels come from?"

"Alfred sent the music,' said his daughter Grace, adjusting a few simple flowers in her sister's hair, with which, in her admiration of that youthful beauty, she had herself adorned it half-an-hour before, and which the dancing had disarranged.

"Oh! Alfred sent the music, did he?" returned the Doctor.

"Yes. He met it coming out of the town as he was entering early. The men are travelling on foot, and rested there last night; and as it was Marion's birth-day, and he thought it would please her, he sent them on, with a pencilled note to me, saying that if I thought so too, they had come to serenade her."

"Ay, ay," said the Doctor, carelessly, "he always takes your opinion." ["Part the First," 24-25, 1912 edition]

Commentary: Various Illustrators’ Presentation of Alfred

In the Household Edition of 1878 Fred Barnard, who had a very limited number of illustrations with which to work, does not include either the musicians or the dancing sisters, perhaps because Daniel Maclise had already visualised both pairs in the 1846 edition's frontispiece, Grace and Marion Jeddler Dancing (see below). Although the picture's charm lies in its rural backdrop, the Green illustration of medical student Alfred Heathfield approaching the itinerant musicians focusses our attention on the young man who is the apex of the romantic triangle with the Jeddler sisters. Respectably dressed in the mid-eighteenth-century manner, exactly as Dickens had envisaged in his instructions to the original illustrators, Alfred stands by himself, as if he has just emerged from the village in the background and yet, by virtue of his stylish urban hat and jacket, is not a part of that bucolic way of life suggested by the thatched-roofed, white-washed buildings. By placing him at the centre of the highly realistic composition, Green has singled him out for our scrutiny, lean, handsome, and (if we examine the text for its implications about his attitude towards the Jeddler sisters) romantically interested in Marion. However, the text accompanying (indeed, framing) the illustration also implies that Grace is similarly interested in Alfred.

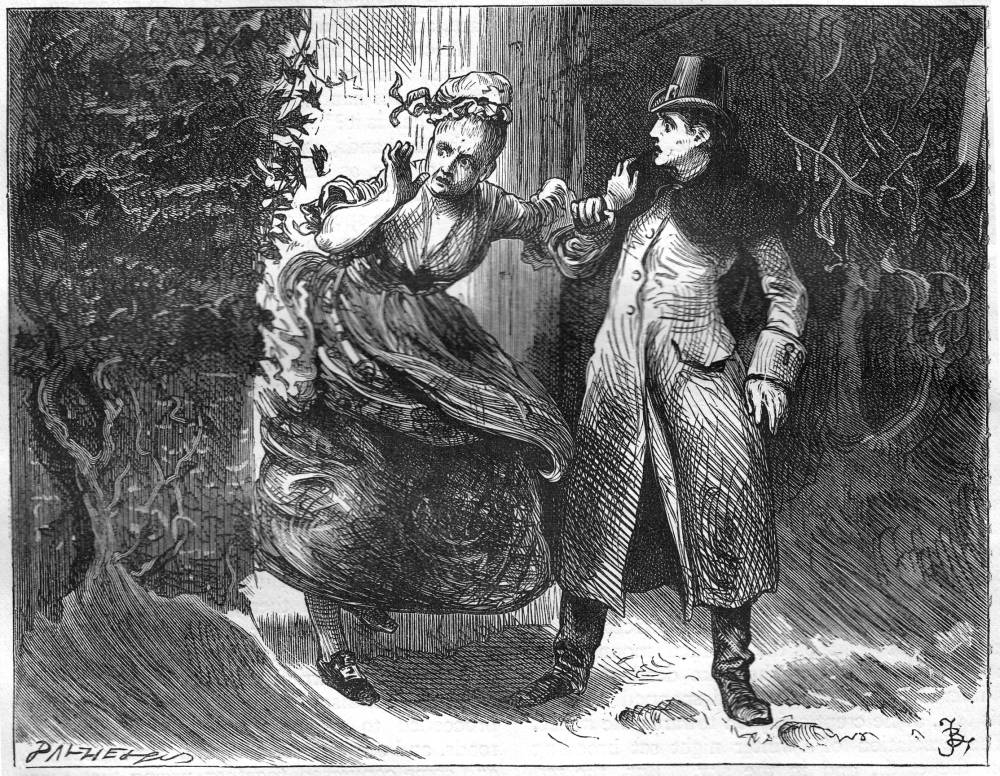

One sees little of Alfred in either Household Edition volume. In the 1876 Harper and Brothers volume, E. A. Abbey depicts Alfred as an emotionally distraught fiance who does not know what has become of Marion on the night of his return, And sunk down in his former attitude, clasping one of Grace's cold hands in his own. Fred Barnard in the 1878 British Household Edition focuses on Alfred's initial reaction to the problem that Clemency has flagged as, a traveller accoutred in the urban fashion of the last decade of the eighteenth century, Alfred meets the servant at the door just after Marion has left, "What is the matter?" he exclaimed. "I don't know. I — I am afraid to think. Go back. Hark!" (see below). Focussing on Alfred once again, but depicting his departure rather than his return to graph the romantic trangle, Harry Furniss in his 1910 lithograph Alfred's Farewell prepares readers for Marion's sacrifice that enables her sister to find happiness with young physician who appears only twice in the 1846 program of thirteen illustrations, and only once in E. A. Abbey's four wood-engravings, barely discernible in the hunched over figure in And sunk down in his former attitude, clasping one of Grace's cold hands in his own. Although he is pivotal to the romantic plot, Alfred apparently only becomes visually interesting when animated by powerful emotions.

Relevant Illustrations from the 1846 and later Editions

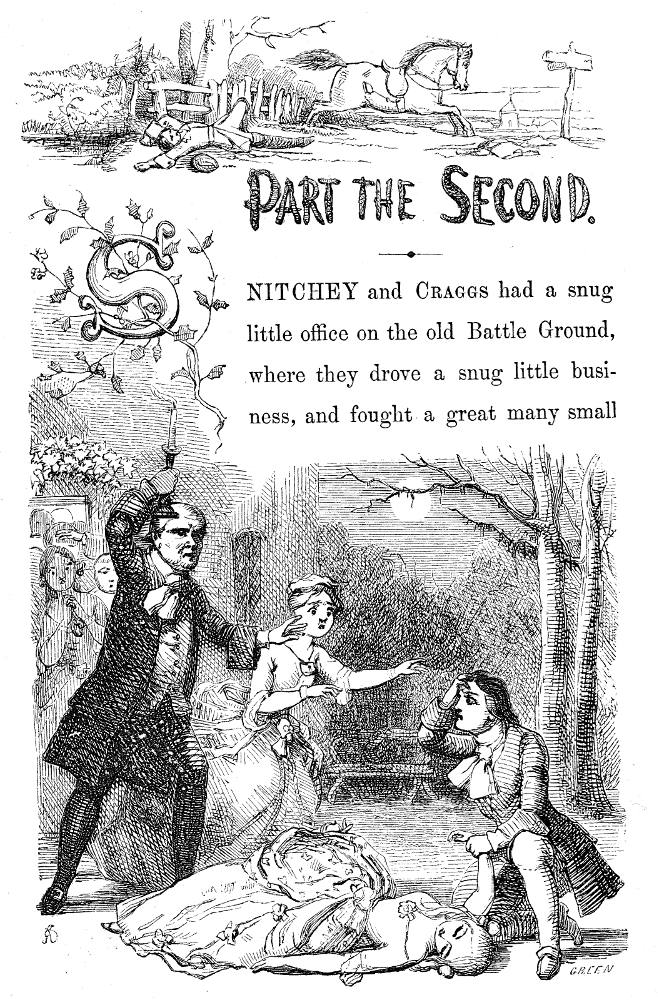

Left: Daniel Maclise's pastoral interpretation of the dancing sisters, Grace and Marion Jeddler Dancing. Right: Richard Doyle's description of the overwrought reactions of Dr. Jeddler, Alfred, and Grace to Marion's disappearance, Part the Second. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

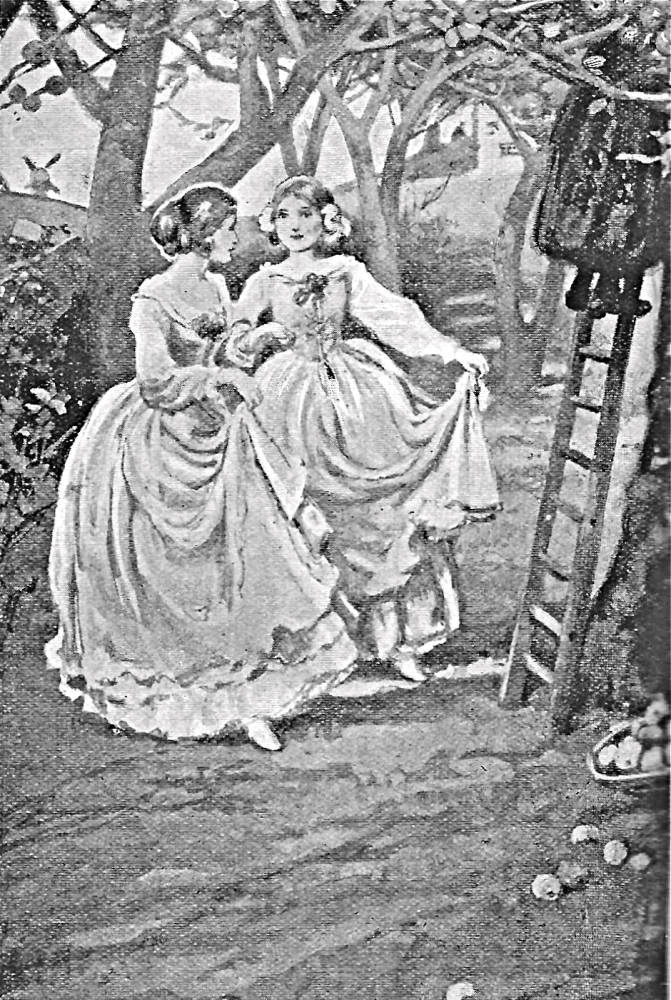

Left: A. A. Dixon's 1906 lithograph of the lookalike sisters dancing in the orchard, Danced in the freedom and gaiety of their hearts. Right: Harry Furniss's pen-and-ink drawing of the sisters' bidding Alfred a reluctant goodbye, Alfred's Farewell (1910).

Above: In Barnard's 1878illustration, a surprised and worried Alfred encounters Clemency at Dr. Jeddler's door on the night of his return from abroad in "What is the matter?" he exclaimed. "I don't know. I — I am afraid to think. Go back. Hark!" (1878).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

_____. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. (1846). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. The Battle of Life. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 9 May 2015

Last modified 17 March 2020