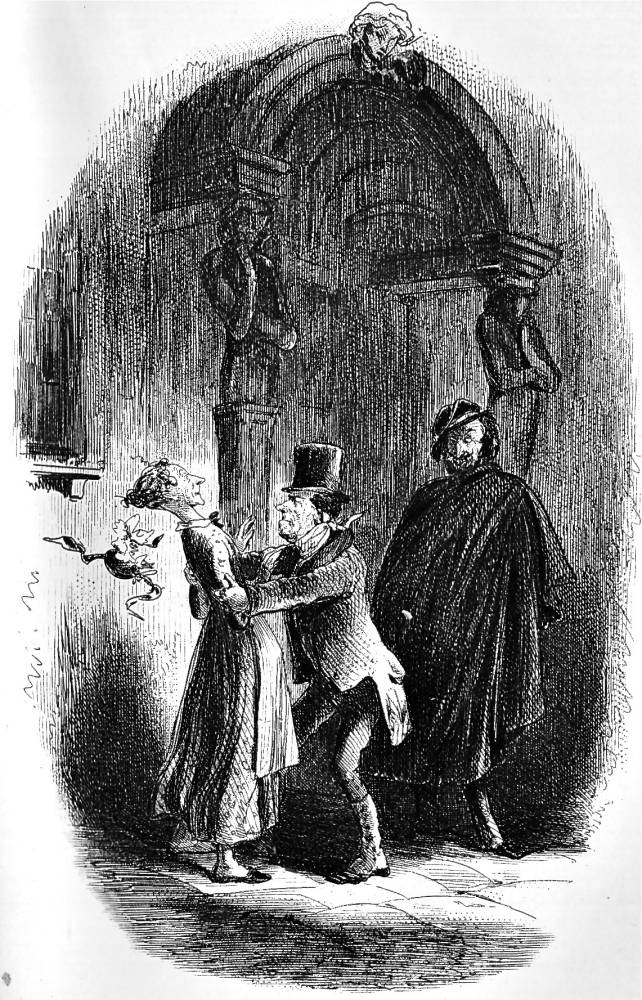

"What's the matter?" he asked in plain English. "What are you frightened at?" — See Page 177. Book I, chap. 29, "Mrs. Flintwinch goes on Dreaming." Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's twenty-third illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. 9.5 cm high x 13.8 cm wide, framed. Page 169. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

In this dilemma, Mistress Affery, with her apron as a hood to keep the rain off, ran crying up and down the solitary paved enclosure several times. Why she should then stoop down and look in at the keyhole of the door as if an eye would open it, it would be difficult to say; but it is none the less what most people would have done in the same situation, and it is what she did.

"From this posture she started up suddenly, with a half scream, feeling something on her shoulder. It was the touch of a hand; of a man's hand.

"The man was dressed like a traveller, in a foraging cap with fur about it, and a heap of cloak. He looked like a foreigner. He had a quantity of hair and moustache — jet black, except at the shaggy ends, where it had a tinge of red — and a high hook nose. He laughed at Mistress Affery's start and cry; and as he laughed, his moustache went up under his nose, and his nose came down over his moustache.

"What's the matter?" he asked in plain English. "What are you frightened at?"

"At you," panted Affery.

"Me, madam?"

"And the dismal evening, and — and everything," said Affery. "And here! The wind has been and blown the door to, and I can't get in." — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 29, "Mrs. Flintwinch goes on Dreaming," p. 176-177.

Commentary

The half-page composite wood-block engraving by the Dalziels occurs embedded in p. 169 in the Chapman & Hall volume, with the running head Miss Wade's Mediation, must be read proleptically since the passage realised occurs eight pages later, in the next chapter. Originally, this section appeared in Part VIII — July 1856 (Chapters 26-29), almost at the mid-point of the story, re-introducing the villainous Rigaud. The caption in the Harper and Brothers (New York) printing of the Household Edition volume is much more extensive: Why she should then stoop down and look in at the key-hole of the door, as if an eye would open it, it would be difficult to say. From this posture she started suddenly, with a half scream, feeling something on her shoulder. It was the touch of a hand; of a man's hand

— Book 1, chap. xxix.The French murderer and confidence man whom we met in the book's opening chapter, Rigaud, now arrives at Mrs. Clennam's house in London towards the end of Book One, finding that Affery through inadvertence occasioned by a thunder storm has locked herself out. Whereas the Harry Furniss version of this scene, Rigaud enters Mrs. Clennam's house exploits both characters' comedic potentials with a comic opera French villain with a nutcracker face, James Mahoney treats both figures more realistically, depicting the storm in the background and eschewing caricature in describing Rigaud's penetrating visage and lithe form. Recently arrived by packet boat, Rigaud takes the unconventional step of visiting the Clennam mansion after business hours, suggesting that he is keen to convert some of the financial papers he carries (possibly purloined) into actual cash. The illustration marks the arrival of the gentlemanly French criminal in London after a journey across all of France which began with his release from the Marseilles prison at the opening of the novel.

In the background, Mahoney has sketched in the rain falling in sheets over an industrial chimney and houses, with an iron railing (upper right) above a six-foot wall to imply the prison-like nature of the Clennam mansion, and a supporting beam to sure up the outer wall foreshadows its eventual collapse. In the foreground, Rigaud (now using the alias "Blandois") fixes a mesmeric gaze on the cringing maid, pinning her against the double entrance-doors of the house, his fur hat and cloak implying his status as a traveller, lately alighted from the continental packet-boat. Since the London to Dover rail route opened only in 1844, Rigaud has likely come from the Continent (probably the Pas-de-Calais) on board a Royal Mail packet-steamer, and then traversed the final leg by stage-coach, or a faster, more expensive mail-coach. By 1833 the packet-boats (with paddle-wheels rather than screw propellers) built by the General Steam Navigation Company were carrying the mails from London to Hamburg, Ostend, Boulogne, and Rotterdam, but the time period of the early part of the novel, the late 1820s, suggests that Rigaud has crossed from Calais.

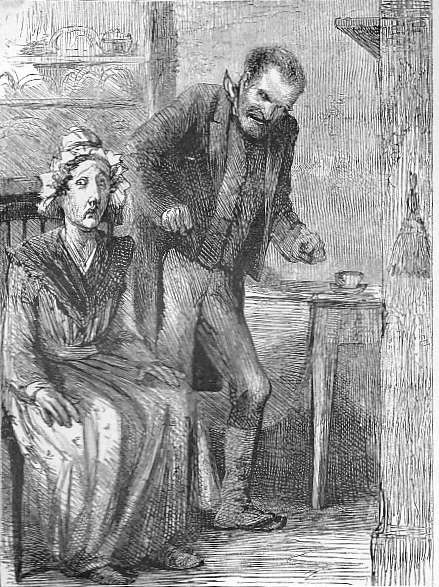

Rigaud and the Flintwinches from Other Early Editions

Left: Phiz's original, Part 9 (August 1856) illustration of the meeting of Rigaud and Flintwinch, Mr. Flintwinch has a mild Attack of Irritability. Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's study of the irritable husband and his anxious wife, Mr.and Mrs. Flintwinch (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's caricatural re-interpretation of the scene in which "Blandois" offers to let Affery back into the house, Rigaud effects an entrance to Mrs. Clennam's house. (1910) [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Harvey, John. Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators. London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1970.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Matz, B. W., and Kate Perugini. Character Sketches from Dickens. Illustrated by Harrold Copping. London: Raphael Tuck, 1924.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 25 May 2016