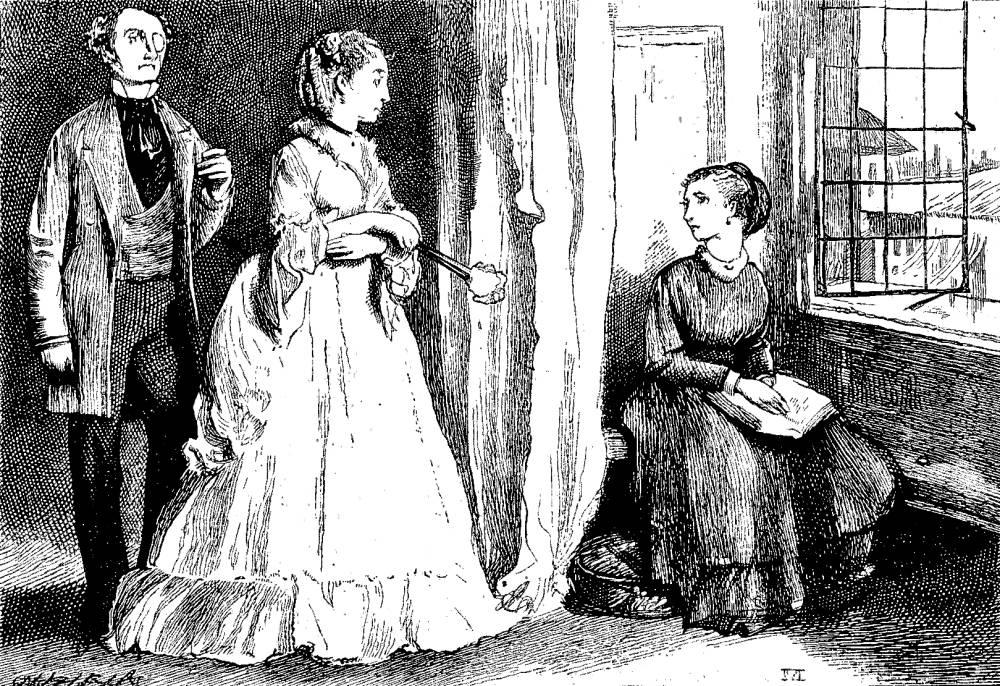

Little Dorrit used to sit and muse here, much as she had been used to while away the time on her balcony in Venice. Seated thus one day, she was softly touched on the shoulder, and Fanny said, "Well, my dear," and took her seat at her side. — Book 2, chap. xiv, is the full title as given in the Harper and Brothers printing. Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's fortieth illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 9.5 cm high by 13.7 cm wide, p. 297, framed, under the running head "Mr. Pancks's Acquaintance Imnproved." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

Little Dorrit was at home one day, thinking about Fanny with a heavy heart. They had a room at one end of their drawing-room suite, nearly all irregular bay-window, projecting over the street, and commanding all the picturesque life and variety of the Corso, both up and down. At three or four o'clock in the afternoon, English time, the view from this window was very bright and peculiar; and Little Dorrit used to sit and muse here, much as she had been used to while away the time in her balcony at Venice. Seated thus one day, she was softly touched on the shoulder, and Fanny said, "Well, Amy dear," and took her seat at her side. Their seat was a part of the window; when there was anything in the way of a procession going on, they used to have bright draperies hung out of the window, and used to kneel or sit on this seat, and look out at it, leaning on the brilliant colour. But there was no procession that day, and Little Dorrit was rather surprised by Fanny's being at home at that hour, as she was generally out on horseback then.

"Well, Amy," said Fanny, "what are you thinking of, little one?"

"I was thinking of you, Fanny."

"No? What a coincidence! I declare here's some one else. You were not thinking of this some one else too; were you, Amy?"

Amy had been thinking of this some one else too; for it was Mr. Sparkler. She did not say so, however, as she gave him her hand. Mr. Sparkler came and sat down on the other side of her, and she felt the fraternal railing come behind her, and apparently stretch on to include Fanny. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 14, "Taking Advice," page 304.

Commentary

The scene is significant in that it marks Fanny's determination to be avenged upon Mrs. Merdle by marrying the foolish, good-natured Edmund Sparkler, despite Amy's advice that such a motive is hardly the basis for a satisfactory marriage, or for a happy life. Fanny further justifies her decision by considering that, as hers is a wilful and vain nature, she would be better off with a husband who not particularly clever or wilful himself (perhaps an oblique allusion to Henry Gowan, who covets the civil service administrative position that Edmund, through his step-father's governmental connects, has just arranged for him). Mahoney underscores the presence of the young man himself in a composition clearly dominated by Fanny as the central figure.

The physical setting is the rooms that the Dorrits have rented in Rome, with Amy in the window-seat, observing life's passing parade rather than joining it as her sister intends to do. The scene prepares the reader for Amy's counselling Fanny not to rush headlong into a marriage based not on a desire to love and be loved, but on a desire for vengeance. The room has extensive curtains, but otherwise Mahoney does not characterize it as a "drawing-room suite, nearly all irregular bay-window, projecting over the street" (304), and the view is hardly "picturesque." Thus, Mahoney focuses the reader's attention upon the contrasting figures of the two sisters: small, modestly, dark-clad Amy in the inferior position, and Fanny in a voluminous white dress backed by dark shading, with pillar-like Edmund jammed in between his fiancée and the left margin. However, since the scene offers little visual engagement or subtlety in detail, it might well be mistaken for a parlour engraving by the illustrator of society fiction George Du Maurier from the same period.

Amy, Fanny, and Edmund Sparkler in other 19th c. series of illustration

Right: Phiz's illustration of Edmund Sparkler's accident in a Venetian gondola, Mr. Sparkler under a Reverse of Circumstances (II: 6, November 1856, Part 12), a scene that establishes Fanny's ability to captivate the awkward, upper-middle-class youth. Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's study of Mrs. Merdle, her vacuous son, and new daughter-in-law, Mrs. Merdle, Mr. Sparkler, and Fanny (1867). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

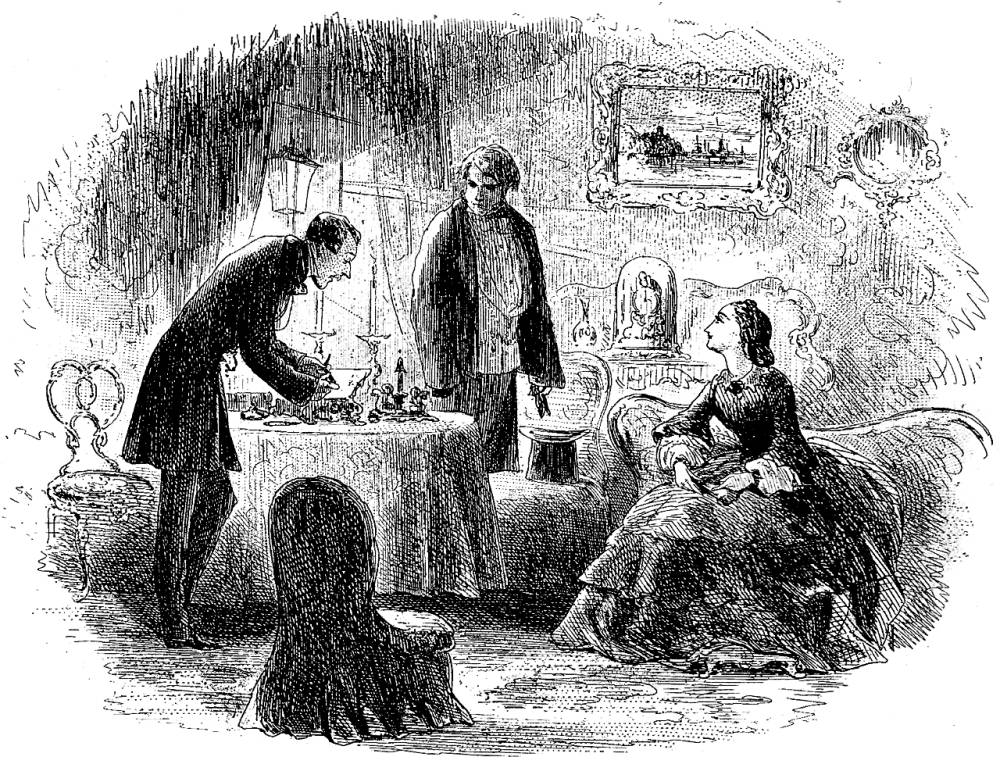

Above: Phiz's study in the original serial of the scene in which Mr. Merdle alls upon Edmund Fanny Sparkler to borrow a penknife, Mr. Merdle Becomes a Borrower (Part 17, April 1857). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 10 June 2016