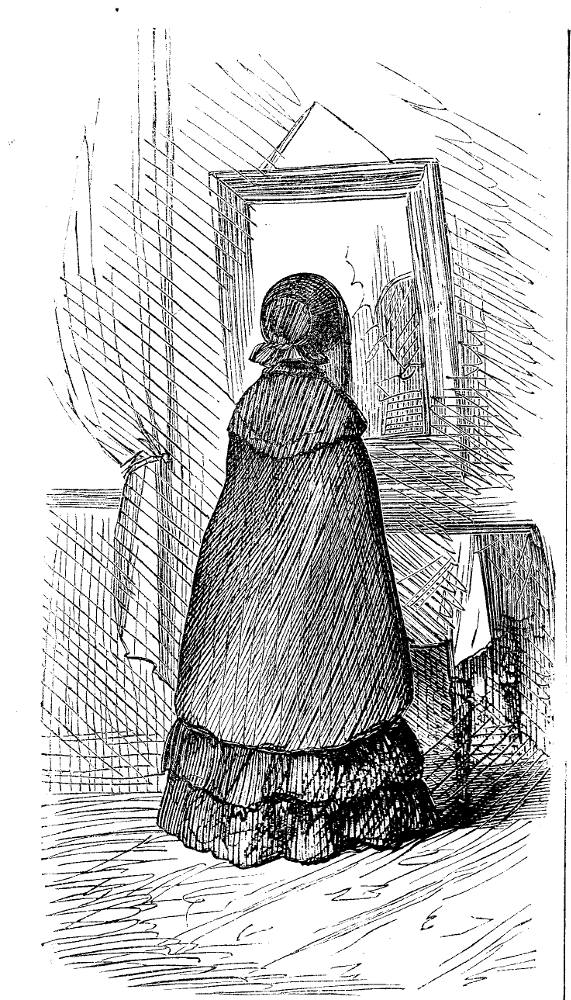

The youngest — a girl of eight or nine years old — flew into a child’s vehement passion, cried, screamed, and even kicked at the governess.” Wood-engraving 11.7 cm high by 11.7 cm wide, or 4 ½ inches square, framed, for instalment seventeen in the American serialisation of Wilkie Collins’s No Name in Harper’s Weekly [Vol. VI. — No. 288] Number 17, “The Third Scene — Vauxhall Walk, Lambeth.” Chapter II (page 422; p. 106 in volume), plus an uncaptioned vignette of Magdalen, in disguise, examining herself in a mirror (p. 109 in volume): 9.7 cm high by 5.6 cm wide, or 3 ⅞ inches high by 2 ¼ inches wide, vignetted. [Instalment No. 17 ends in the American serialisation on page 423, at the end of Chapter II. Precisely the same number without illustration ran on 5 July 1862 in All the Year Round.]

Passage Illustrated in the Vignette: Magdalen Examines Her Disguise in a Mirror

Before unlocking the door, she looked about her carefully, to make sure that none of her stage materials were exposed to view in case the landlady entered the room in her absence. The only forgotten object belonging to her that she discovered was a little packet of Norah’s letters which she had been reading overnight, and which had been accidentally pushed under the looking-glass while she was engaged in dressing herself. As she took up the letters to put them away, the thought struck her for the first time, “Would Norah know me now if we met each other in the street?” She looked in the glass, and smiled sadly. “No,” she said, “not even Norah.” [Chapter II: page 422 in serial; pp. 108-109 in volume]

Passage Illustrated in the Main Illustration: Norah's Fractious Charges Act Up

Norah and the two children had reached the higher ground, and were close to one of the gates in the iron railing which fenced the Park from the street. Drawn by an irresistible fascination, Magdalen followed them again, gained on them as they reached the gate, and heard the voices of the two children raised in angry dispute which way they wanted to walk next. She saw Norah take them through the gate, and then stoop and speak to them, while waiting for an opportunity to cross the road. They only grew the louder and the angrier for what she said. The youngest — a girl of eight or nine years old — flew into a child’s vehement passion, cried, screamed, and even kicked at the governess. The people in the street stopped and laughed; some of them jestingly advised a little wholesome correction; one woman asked Norah if she was the child’s mother; another pitied her audibly for being the child’s governess. Before Magdalen could push her way through the crowd — before her all-mastering anxiety to help her sister had blinded her to every other consideration, and had brought her, self-betrayed, to Norah’s side — an open carriage passed the pavement slowly, hindered in its progress by the press of vehicles before it. An old lady seated inside heard the child’s cries, recognized Norah, and called to her immediately. The footman parted the crowd, and the children were put into the carriage. “It’s lucky I happened to pass this way,” said the old lady, beckoning contemptuously to Norah to take her place on the front seat; “you never could manage my daughter’s children, and you never will.” The footman put up the steps, the carriage drove on with the children and the governess, the crowd dispersed, and Magdalen was alone again.

“So be it!” she thought, bitterly. “I should only have distressed her. We should only have had the misery of parting to suffer again.” [Chapter II: page 422 in serial; pp. 110-111 in volume]

Commentary on the Vignette and Main Plate: Magdalen’s Progress; Norah’s Challenges

Whereas Magdalen has adopted the highly unusual expedient of investigating Michael Vanstone and his son Noel, donning a disguise as she moves to Lambeth in Greater London, her older sister has entered the profession that Victorian society deemed suitable for young women of good backgrounds who had fallen on hard times, and become a much-harassed governess. Although the acting out of the difficult daughters is a minor incident in the chapter, it lends itself to vivid realisation. Furthermore, Mclennan’s illustration has considerable intelligibility even when viewed from outside the context of the novel.

In her padded grey cloak purchased in Birmingham Magdalen looks nothing like her youthful self. She has added to the effectiveness of the disguise by counterfeiting a suitable limp, voice (complete with Northumbrian burr), and manner in imitation of Miss Garth, her fifty-year-old governess. Her test of the disguises’s effectiveness involves calling upon Noel Vanstone and asking to see his housekeeper, Mrs. Lecount. Meanwhile, as she whiles away the time until the housekeeper will return, Magdalen contemplates the situation that Norah has described in her recent letters: she determines to drive to the house of Norah’s employer. Arrived, she follows Norah and her charges into nearby St. James’s Park, and thence to Green Park.

Although the physical setting is not entirely obvious, Mcleanan is utilizing the pavement on the other side of the road from the park, as Collins suggests. However, the illustrator has had to furnish many details from his own New York experiences of children, their minders, and casual observers on urban sidewalk. McLenan gives us three, rather common types: an elderly woman carrying a basket (left), and two rather plebeian males, lightly sketched in. His focus, then, is the foregrounded Norah, in mourning, her face hidden by her bonnet, and the two affluent children. All that the novelist tells us is that the fabric of their dresses is silk, in contrast to the much coarser fabric of the governess’s clothing. The illustrator, therefore, has invented outlandish, feathered hats, and ornamentally worked skirts: clothing that seems artificially “fashionable” and excessive, as if to suggest the garish nouveau-riche tastes of the girls’ wealthy parents. Although their clothing sets the girls apart, McLenan relies on the bad behaviour of the younger child, caught in the midst of action, vigorously kicking the knees of her governess in a fit of pique. The impoverished Norah must bear the indignity with a good grace, and Magdalen must betray no sympathy for her sister.

Related Material

- The Victorian Governess Novel

- Frontispiece to Wilkie Collins’s No Name (1864) by John Everett Millais

- Victorian Paratextuality: Pictorial Frontispieces and Pictorial Title-Pages

- Wilkie Collins's No Name (1862): Charles Dickens, Sheridan's The Rivals, and the Lost Franklin Expedition

- "The Law of Abduction": Marriage and Divorce in Victorian Sensation and Mission Novels

- Gordon Thomson's A Poser from Fun (5 April 1862)

- Kate Egan's Playthings to Men: Women, Power, and Money in Gaskell and Trollope

- Philip V. Allingham, The Victorian Sensation Novel, 1860-1880 — "preaching to the nerves instead of the judgment"

Image scans and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Blain, Virginia. “Introduction” and “Explanatory Notes” to Wilkie Collins's No Name. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.