Walter Paget's illustrations for Hardy's "On the Western Circuit" appeared in the English Illustrated Magazine in December 1891, with an ornamental headpiece and tailpiece.

The Illustrations (December 1891)

- Headpiece, "Let not the flowers of spring pass us by let us crown ourselves with roses before they be withered." and Initial "T." [C. M. C.]

- "'It is mine,' she said."

- "It was a most charming little epistle."

- "'I wish he was mine!' she murmured"

- "'I think I have one claim upon you.'"

- "The End." [C. M. C.]

Commentary

Thomas Hardy presented the manuscript of his short story, 'On the Western Circuit', to Manchester Central Public Library in 1911. The story had been written in the latter half of 1890 or the early months of 1891. . . . The most interesting and extensive of [Hardy's] revisions [both before and after periodical publication] concern the story's bowdlerization for the serial versions [in England and America] and Hardy's later partial restoration of his original conception of the story [for publication in volume form in 22 February 1894 for the Osgood, McIlvaine Life's Little Ironies]. — Martin Ray, p. 201.

As in "To Please His Wife," in "On the Western Circuit," also written in 1891, two women of very different social backgrounds are attracted to the same man, but with a markedly contemporary and urban/bourgeois context. Sydney Paget's brother, Wal, who would later illustrate The Pursuit of the Well-Beloved for The London Illustrated News, has provided a program of an ornamental headpiece in the Pre-Raphaelite style ("Let not the flowers of spring pass us by let us crown ourselves with roses before they be withered."), an embellished initial "T" (with a cat and two kittens below and a raven above), a decorative tail-piece, and four vignetted plates dropped into the text of the English Illustrated Magazine for December 1891, the precise positions for placement probably determined by editor Clement Shorter through pages 275-288. Despite the central role that the lady, Edith Harnham, plays in the romantic triangle, the illustrations focus on her country maid, Anna, and the urban barrister Charles Raye.

The differences between the American and English serial texts are substantive, including the fact that Haper's Weekly (28 November 1891) did not merely re-print Paget's illustrations, but instead used a single illustration by American artist W. T. Smedley, perhaps owing to copyright considerations since the story would be covered by American copyright if its illustrator were an American, even though the author was British. Oddly enough,

HW is closer to the MS. than is EIM; of all the pairs of variant readings which differentiate the two serial versions, twice as many of the HW readings are found in the MS., rather than the EIM wording. Thus, EIM apparently underwent further proof revisions after HW had been sent to America. — Martin Ray, Chapter 22, "On the Western Circuit," p. 207-208.

Utilizing a biblical quotation from King Solomon's "The Book of Wisdom" (II, 6-11) also used by George Eliot for the headnote of the third chapter of Daniel Deronda, the ornate, mediaeval-idiomed headpiece may be interpreted as representing Edith Harnham's intense, "impassioned and pent up ideas" (283), the more educated woman's "foisted-in sentiments to which the young barrister . . . responded" (283) rather than those of her maid, the sensitive but naive Anna. On either side of the Fountain of Youth cherubs (repeated in the ornamental Tailpiece) hover above a young man and a young woman, both kneeling, with female figures also dressed in mediaeval fashion standing behind them, to the right and left. The symbolic scene's ritualistic presentation suggests the enactment of a betrothal ceremony, ironic in that two of the romantic principals of the story are older and somewhat experienced. As the young man offers an apple (indicative, perhaps, of passion and emotional self-fulfilment), the young woman reaches forward to accept his gift with both hands. The headpiece is thus indicative of conventionalized notions of courtly romance which grip Edith Harnham's imagination and inspire her letters, originally written on behalf of her illiterate maid Anna to the circuit attorney Charles Raye.

Despite her pivotal position in the love triangle, Paget has shown her only once in his sequence, perhaps in order to avoid the issue of her pregnancy, which is never actually mentioned in the periodical text, although perhaps hinted at in the widow's regarding wanting Raye for herself as "a wicked thing" (284), a self-castigation that makes more sense if his physical intimacy with Anna has resulted in a condition that necessitates marriage. Rather, Paget focuses on the lawyer, shown twice, and the wine-merchant's widow, not a married woman placed in a morally compromising position as in the revised text, and in pronounced mourning.

Two of these three plates are individual studies, showing a detached Charles Raye perusing "the most charming epistle" (280) in his London chambers, and the lonely Edith Harnham, crying in anguish at her writing desk, just having responded to one of Raye's letters: "she would bow herself on the back of her chair and weep" (284), not so much a detached moment as a repeated action over time. In fact, both poses are habitual rather than particular moments.

Throughout the sequence, moreover, one has a sense of misappropriation, of a character's laying claim (as with the "mantle of Elijah" mackintosh and the verses pencilled on the wall that Ella appropriates in "An Imaginative Woman," 1894) to something or someone not properly his or hers. The first plate in Paget's sequence, "'It is mine,' she said" (277) is also habitual in that it depicts Anna's meeting the postman to claim correspondence that comes in answer to letters she herself has not written. Paget shows the letter-carrier making an interrogative gesture, as if he is incredulous that an envelop bearing a postmark from the metropolis could possibly be directed to a mere illiterate servant-girl from a remote village on the Salisbury Plain. Curiously, the layout artist has inserted the vignetted illustration out of sequence: although it realizes a moment early in the fourth part (bottom, p. 281), it is juxtaposed against the textual moment of Raye's watching Anna and Anna's watching Raye on the merry-go-round at the outset of the story. Thus, the periodical's version of the story telegraphs the correspondence aspect of the plot well before the pair begin to exchange letters. When the readers encounter this initial illustration, they are not aware that Anna is actual incapable of indicting an intelligible piece of prose, since (as Hardy remarks) ever since her husband's death Edith Harnham has been "taking the trouble to educate" (276) her young maid.

Although Edith Harnham has been introduced to readers via the letterpress in part one, she does not enter the narrative-pictorial sequence until the close of part four, so that, while the thirty-year-old widow is the focus of the story as it appeared in The English Illustrated Magazine for December 1891, until the ninth page the principal figures appearing in the illustrations are the circuit-court attorney and the housemaid. So greatly is Edith Harnham's "hidden life" revealed in her correspondence in the adopted persona of Anna that she has been seduced "by the persuasiveness of her own fiction" (Gilmartin and Mengham 99). The anguish of the picture captioned "'I wish he was mine!' she murmured" (moment illustrated, p. 284; illustration, p. 283) reflects the writer's realization that only textually, so to speak, is she Raye's, and that what Hardy terms "vicarious intimacy" (284) she is finding inadequate emotionally, and yet such possession is the best she can expect since she feels morally compelled to secure Raye as a husband for the uneducated Anna. Ensnared imaginatively by her own romantic correspondence, Edith must now use her skill as a writer (exemplified by the writing desk in the third illustration, p. 283) to entrap a man who makes his living with the spoken and written word.

Thus, the narrative-pictorial sequence culminates not in the almost clandestine wedding of Anna and Charles, but in the recognition scene of "'I think I have one claim upon you'" (287). Whereas the tone and form of the letterpress on the same page involve the vocabulary and manner of a terse legal cross-examination, with Raye enacting the role of the prosecutor or Crown Attorney and Edith as the accused who is "brought to book," the plate is thoroughly romantic, as the tall, well-dressed, amorous attorney steps towards the young widow and clutches the hand that has literally penned him an unequal and, from his perspective, socially ruinous union. As in the text, he approaches her, drawing her towards him and bending over her (288), a moment of tenderness for which the illustrator has prepared readers, even as the barrister conducts his discovery of the true nature of the delusion he has suffered. These soberly attired, middle-class late Victorians enact the romantic idyll of the "Pre-Raphaelite" headpiece some twelve pages earlier. Ironically, while the text juxtaposes sexual intimacy without regard for compatibility against imaginative erotic engagement ("romance"), the program of illustration focuses entirely on the latter. This emphasis is natural in a periodical story that must suppress the physical dimension, expunging any direct reference to Anna's pregnancy but implying it in such lines as "the next morning she declared she wished to see her lover about something" (283).

The social dimension of a romantic liaison intrudes at the close of the letterpress. The wife who will tend Raye's home and hearth (depicted in Paget's second illustration, p. 281) will not be the woman with whom over a number of months he has contracted an intellectual and emotional "bond" (288). He recognizes ironically that his own unworthy actions stemming from his seduction of a naive village girl and not the correspondence composed by her employer have "ruined" him professionally and socially. As in the letterpress, in the final illustration Raye fulfills Edith Harnham's romantic yearnings, the picture if taken out of context suggesting a mutual emotional fulfilment, foiling the Hardyesque imagery in which Raye, "the fastidious urban" (288) regards himself as chained metaphorically, like a galley slave, to labour at the oar for the remainder of his life alongside "the unlettered peasant."

This passage occurs just a few inches above the romantic tailpiece of a male and female cupidon holding up an open book reading "The End [CMC]." These classical figures, symbolic of pure passion as opposed to mature attraction, only serve to underscore the discrepancy between the story’s two texts, the visual and the print, as if the reader is being permitted to choose between a realistic and a romantic conclusion. Since "On the Western Circuit" deals with "the untrustworthiness of language" (Gilmartin and Mengham 103), the magazine reader must soon have suspected that the narrator's judgments, like those of all three principal characters, are not wholly reliable, and that even the images cannot be taken out of context. The concluding illustration and tailpiece are as misleading as Edith Harnham's correspondence to Charles Raye, and without the letterpress represent at best an incomplete closure.

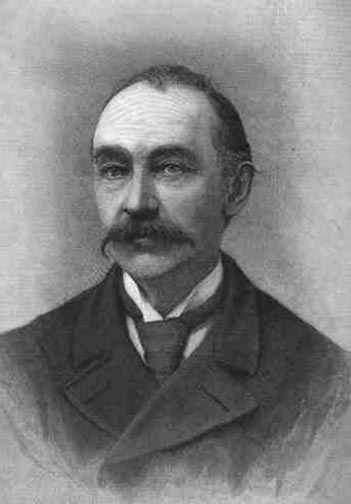

A Contemporary photograph of Hardy, and the story's 1896 Illustration

Left: The 1892 photograph at the beginning of the serialisation of The Well-Beloved in the Illustrated London News, Mr. Thomas Hardy the Novelist (1 October 1892). Right: Henry Macbeth-Raeburn's frontispiece for the 1896 volume Life's Little Ironies, A view in "Melchester". [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Additional Resources on Hardy's Short Stories

References

Brady, Kristin. The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy. London and Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1982.

Cassis, A. F. "A Note on the Structure of Thomas Hardy's Short Stories." Colby Library Quarterly 10 (1974): 287-296.

Gilmartin, Sophie, and Rod Mengham. Thomas Hardy's Shorter Fiction: A Critical Study. Edinburgh: Edinburgh U. P., 2007.

Hardy, Thomas. Life's Little Ironies, A Set of Tales, with Some Colloquial Sketches Entitled "A Few Crusted Characters". Illustrated by Henry Macbeth-Raeburn. Volume Fourteen in the Complete Uniform Edition of the Wessex Novels. London: Osgood, McIlvaine, 1894, rpt. 1896.

Hardy, Thomas. "On the Western Circuit." The English Illustrated Magazine. December 1891, pages 275-288.

Jackson, Arlene M. Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Totowa, New Jersey: Rowman and Littlefield, 1981.

Johnson, Trevor. "Illustrated Versions of Hardy's Works: A Checklist, 1872-1992." Thomas Hardy Journal 9, 3 (October, 1993): 32-46.

Millgate, Michael. Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2004.

Page, Norman. "Hardy Short Stories: A Reconsideration." Studies in Short Fiction 11, 1 (Winter, 1974): 75-84.

Pinion, F. B. A Hardy Companion. Trowbridge, Wiltshire: Macmillan, 1968.

Purdy, Richard L. Thomas Hardy: A Bibliographical Study. Oxford: Clarendon, 1954, rpt. 1978.

Quinn, Marie A. "Thomas Hardy and the Short Story." Budmouth Essays on Thomas Hardy: Papers Presented at the 1975 Summer School (Dorchester: Thomas Hardy Society, 1976), pp. 74-85.

Ray, Martin. Chapter 22, "'On the Western Circuit'." Thomas Hardy: A Textual Study of the Short Stories. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997. Pp. 201-217.

Last modified 10 February 2017