Mr. Chadband 'Improving' a Tough Subject by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne) for Bleak House, facing p. 254 (Part Eight, October 1852: ch. 24, "An Appeal Case"). 4 x 6 1/4 inches (10 cm by 15.5 cm). For text illustrated, see below. [Return to text of Steig.] [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated

"Peace, my friends," says Chadband, rising and wiping the oily exudations from his reverend visage. "Peace be with us! My friends, why with us? Because," with his fat smile, "it cannot be against us, because it must be for us; because it is not hardening, because it is softening; because it does not make war like the hawk, but comes home unto us like the dove. Therefore, my friends, peace be with us! My human boy, come forward!"

Stretching forth his flabby paw, Mr. Chadband lays the same on Jo's arm and considers where to station him. Jo, very doubtful of his reverend friend's intentions and not at all clear but that something practical and painful is going to be done to him, mutters, "You let me alone. I never said nothink to you. You let me alone."

"No, my young friend," says Chadband smoothly, "I will not let you alone. And why? Because I am a harvest-labourer, because I am a toiler and a moiler, because you are delivered over unto me and are become as a precious instrument in my hands. My friends, may I so employ this instrument as to use it to your advantage, to your profit, to your gain, to your welfare, to your enrichment! My young friend, sit upon this stool." . . .

It happens that Mr. Chadband has a pulpit habit of fixing some member of his congregation with his eye and fatly arguing his points with that particular person, who is understood to be expected to be moved to an occasional grunt, groan, gasp, or other audible expression of inward working, which expression of inward working, being echoed by some elderly lady in the next pew and so communicated like a game of forfeits through a circle of the more fermentable sinners present, serves the purpose of parliamentary cheering and gets Mr. Chadband's steam up. From mere force of habit, Mr. Chadband in saying "My friends!" has rested his eye on Mr. Snagsby and proceeds to make that ill-starred stationer, already sufficiently confused, the immediate recipient of his discourse.

"We have here among us, my friends," says Chadband, "a Gentile and a heathen, a dweller in the tents of Tom-all-Alone's and a mover-on upon the surface of the earth. We have here among us, my friends," and Mr. Chadband, untwisting the point with his dirty thumb-nail, bestows an oily smile on Mr. Snagsby, signifying that he will throw him an argumentative back-fall presently if he be not already down, "a brother and a boy. Devoid of parents, devoid of relations, devoid of flocks and herds, devoid of gold and silver and of precious stones. Now, my friends, why do I say he is devoid of these possessions? Why? Why is he?" Mr. Chadband states the question as if he were propounding an entirely new riddle of much ingenuity and merit to Mr. Snagsby and entreating him not to give it up. [Chapter XXV, "Mrs. Snagsby sees it all," 253-254; Project Gutenberg etext (see bibliography below)]

Commentary

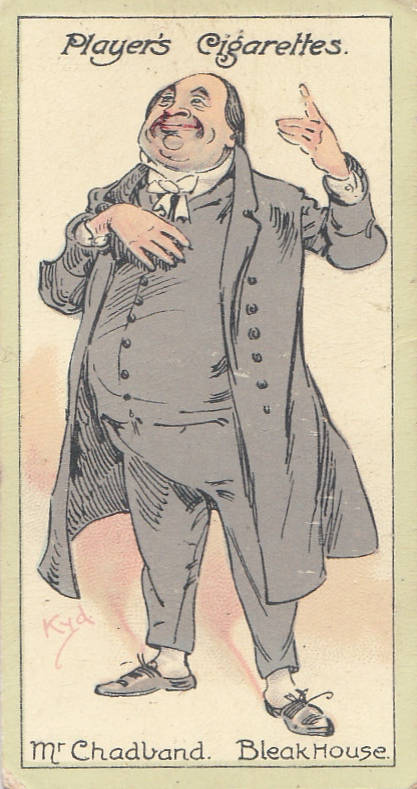

Kyd's version of the self-righteous preacher in the Player's Cigarette Card series, Card No. 50: Mr. Chadband (1910).

Phiz here beautifully captures one of Dickens's oily Evangelical clergymen. From the begining of his career, the novelist presents Evangelicals preying upon women, and although Chadband is not quite as despicable as Stiggins from the Pickwick Papers, since he does not appear as an alcoholic cadging food and drink from a poor family, his combination of self-satisfaction, clichés, and rhetorical questions makes his preaching to Jo particularly despicable. Bleak House contrasts the hypocritical self-serving false religiosity of Chadband with the truer Christianity of both Esther and Woodcourt.

Jo, whom Chadband makes the target of his preaching in this passage illustrated by this plate, has the last word on the preacher and many missionaries to the poor: after Woodcourt asks the dying boy, "Did you ever know a prayer?" Jo responds:

"No, sir. Nothink at all. Mr. Chadbands he wos a-prayin wunst at Mr. Snagsby's and I heerd him, but he sounded as if he wos a-speakin to hisself, and not to me. He prayed a lot, but I couldn't make out nothink on it. Different times there was other genlmen come down Tom-all-Alone's a-prayin, but they all mostly sed as the t'other 'wuns prayed wrong, and all mostly sounded to be a-talking to theirselves, or a-passing blame on the t'others, and not a-talkin to us. We never knowd nothink. I never knowd what it wos all about." [Ch. XLVII, "Jo's Will," 458]

Dickens, I should add, does not seem to criticize Evangelical Anglicans — that is, Evangelicals within the established Church — and he claimed "one of my most constant and most earnest endeavours has been to exhibit in all my good people some faint reflections of our great Master, and unostentatiously to lead the reader up to those teachings as the great source of all moral goodness. All my strongest illustrations are drawn from the New Testament; all my social abuses are shown as departures from its spirit; all my good people are humble, charitable, faithful, and forgiving" ("Letter to Reverend D. Macrae").

Dickens revels in having oily hypocrites such as the Reverend Mr. Chadband reveal themselves. Although he makes a great show of his religiosity, he always considers his own interests and is by no means underfed. Snagsby, the stationer, is naturally suspicious of the nonconformist preacher, but Mrs. Snagsby adores him. A significant association with the main plot is Mrs. Chadband's having once been the maid of Miss Barbary, Lady Dedlock's sister. The illustrators catch the dissenting minister in a tandard pose: he unctuously raises his hand whenever he is about to utter a homily, which he usually introduces with a rhetorical question. In contrast to his placid, well-rounded features, Mrs. Chadband is a severe-looking. Later he teams up with the Smallweeds in a plot to blackmail the Dedlocks about the illicit relationship between Lady Dedlock and Captain Hawdon.

The parallel to [Mr. Turveydrop in the previous illustration,] Mr. Chadband suggests that this oily individual represents another case of the same thing — the deluding of the lower middle classes through a form of Christianity which is essentially no different from the religion of Deportment. Three details provide further comment on the specious preacher. Immediately beneath his outstretched arm and imitating its angle is a toy trumpet, which suggests that Chadband is blowing his own tinny little horn, like the self-puffer on the cover design. Above the chimneypiece are two symbols which suggest the spuriousness of Chadband's religious pretensions: a fish, one of the conventional symbols for Christ, is preserved under glass, but its mouth is open and its eyes regard Cbadband with astonishment. And on the mantel itself a human figure resembling Jo huddles under a bell jar; on either side are shepherd figures with sheep. These elements represent the isolation of Jo from pastoral aid, the traditional church being indifferent to him and the pseudo-clergyman Mr. Chadband preaching at him for self-aggrandizement rather than out of compassion. [Steig, 142-143]

Harry Furniss's Version of the Rhetorical Evangelical in Other Editions

Left: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s 1867 Diamond version of the fat and fatuous Chadband: Mr. and Mrs. Chadband and the Snagsbys. Right: Harry Furniss's reinterpretation of the scene expands the figure of Chadband: Chadband at the Snagsbys (1910).

Related Material, including Other Illustrated Editions of Bleak House

- Bleak House (homepage)

- Sir John Gilbert's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 4, 1863)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 61 illustrations for the Household Edition (1872)

- Harry Furniss's Illustrations for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's five Player's Cigarette Cards, 1910

Image scan and text by George P. Landow; additional text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). London: Bradbury & Evans. Bouverie Street, 1853.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Project Gutenberg etext prepared by Donald Lainson, Toronto, Canada (charlie@idirect.com), with revision and corrections by Thomas Berger and Joseph E. Loewenstein, M.D. Seen 9 November 2007.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 6. "Bleak House and Little Dorrit: Iconography of Darkness." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 131-172.

Vann, J. Don. "Bleak House, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, October 1846—April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 69-70./

Created 13 November 2007 Last modified 7 March 2021