This review is reproduced here by kind permission of Professor Bury and the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where the review was first published. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee. Click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information.

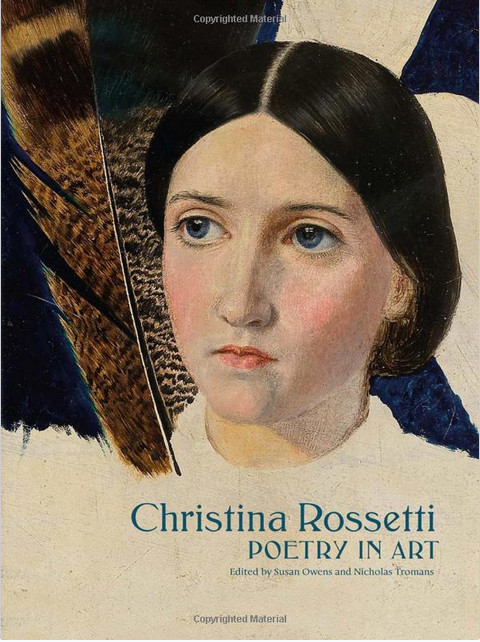

Obviously, after Christina Rossetti and Illustration, published in 2002 by Ohio University Press, it may seem difficult to bring anything really new to our knowledge of the relation between the greatest poetic voice of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the pictures conceived by several generations of artists to accompany her work. Lorraine Janzen Kooistra’s exhaustive study covered one and a half century in the history of publishing, and even boasted sixteen colour plates. However, the volume now published by Yale University Press, in relation with an exhibition on display at the Watts Gallery in Compton, Surrey, does manage to shed some new light on a largely overlapping subject. The book edited jointly by Nicholas Tromans, former curator at the Watts Gallery, and Susan Owens, former curator of paintings at the Victoria & Albert Museum, is aimed at a cultivated audience and makes no claim to scholarly revelation. However, while it discusses the relation between Christina Rossetti and illustration, as well as the independent works of art inspired by her poems, just like Kooistra did, it does so in a different manner; this volume also ventures in a few other directions, being clearly divided into five chapters which explore various aspects of the links between poetry and art.

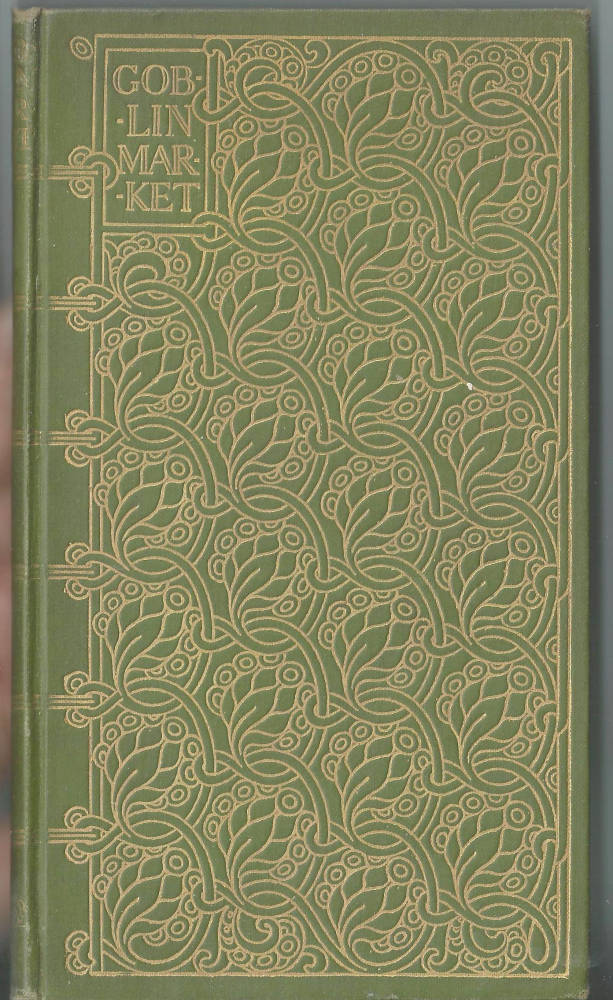

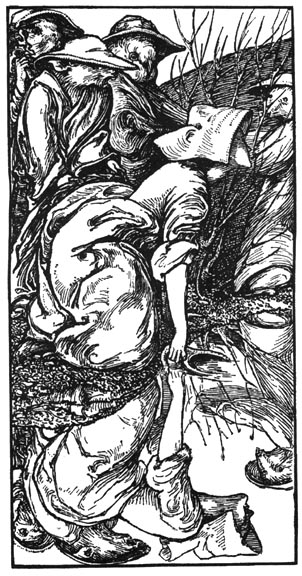

left: Laurence Housman's binding for Goblin Market. Right: One of Housman's illustration for the poem.

Illustrations for Christina Rossetti’s texts having already been widely commented upon, it is a rather brilliant idea to have commissioned a paper by a book collector rather than a literary or art critic. Among the captions, the words “Collection of Stephen Calloway” repeatedly strike the eye, and one can only imagine how many precious volumes belong to the author of that chapter. Himself a former curator at the V&A, Calloway adopts a strictly historical approach to his subject, from the very first images conceived to accompany one of Rossetti’s works to some of the most recent adaptations (artist’s books and graphic novels). He pays a great deal of attention to the “decadent” colours and audacious decor of the bindings designed by Dante Gabriel for his sister’s volumes, as opposed to the ultra-conservative appearance of her religious books, and gets into the details of Christina’s dealings with her publishers. Stephen Calloway hardly ventures to comment on Rossetti’s texts, and simply calls Speaking Likenesses “the oddest of all [her] writings” (126), but he situates Laurence Housman’s 1897 version of Goblin Market in the “book beautiful” trend of the 1890s, as the embodiment of “a new spirit of delicacy” (139). And he interestingly depicts the explicitly adult adaptation published by Playboy of 1973 as “ahead of much of the now widespread exploration of such themes in academic studies” (144).

George Henry Boughton's The Leaf, 1876.

Unfortunately, the final chapter, devoted to the independent pictures inspired by Christina Rossetti’s poems, does not allow the authors to end with a bang. Joined by Hilary Underwood, Curatorial Advisor at the Watts Gallery, Owens and Tromans follow the chronological order from George Chapman’s (untraced) Three Sisters Sang of Love Together (1863), which apparently displeased the poet, to Constance Phillott’s The Ghost (1922). This does not really allow them to identify any profound trend in the way Rossetti’s texts were interpreted, especially as it was quite common practice for nineteenth-century painters to add a few lines from a poem as a vague commentary to the works they exhibited. Beside the well-known works by Belgian symbolist Fernand Khnopff, one is intrigued to hear about a possible link, mentioned by Van Gogh, between Christina Rossetti and George Henry Boughton, an extremely conventional Anglo-American artist (156).

A whole chapter is devoted to the drawings Rossetti herself added in an edition of John Keble’s The Christian Year belonging to her sister. L.J. Kooistra also discussed them in her book, and Dinah Roe acknowledges her debt to an article Diane D’Amico wrote on the same subject. As this is an art book rather than an academic publication, the reader will enjoy the splendid reproductions of those amateurish, almost child-like illustrations (only a few among the 109 to be found in the volume now on loan to the British Library). In her erudite analysis, Dinah Roe, Senior Lecturer at Oxford Brookes University, refers to Christina Rossetti’s ideal of “self-effacement in the service of faith” (83), her drawings being “meditations ... rather than literal illustrations of” Keble’s poems (88). Through introspection (the “inward gaze”) and the contemplation of the dazzling brightness of God’s creation, Rossetti aimed at “discerning the invisible in the visible, the symbolic in the material” (107). It is still possible to compare the poet’s naive but daring drawings in her manuscript of Sing-Song with the more acceptable versions by Arthur Hughes, but unfortunately, nobody knows what became of the illustrations Christina Rossetti herself added on the pages of her very first publication, Poems (1847), or of her watercolours for Goblin Market.

Christina (sitting on the steps) with her mother and brothers, photographed by Lewis Carroll.

Phrases like “untraced,” “present whereabouts unknown,” or “location unknown,” recur all too frequently in the book, which is replete with comments about the “tantalising” fact that George Frederick Watts did not have time to paint the planned portrait of Christina Rossetti in his Hall of Fame, where she would have been the only woman included (79), or the “frustrating” vanishing of a photograph of the poet by Julia Margaret Cameron (74). The chapter about the poet’s “evolving appearance in portraits and in Pre-Raphaelite Compositions” (13) is filled with gorgeous works by her brother, by her one-time suitors, the painters James Collinson and John Brett, and with photographs taken at various moments of her life, once she had become a public figure. Examining the effigies produced by those who “str(ove) to understand her enigmatic personality” (43), Susan Owens concludes that Rossetti was all things to all men, after her own fashion.

One might be surprised by the multiplication of hypothetical wordings like “we might imagine” (52) or “It is not unimaginable that” (88), such contorted assertions being particularly present in Nicholas Tromans’s chapter about the poet’s “complicated attitude to pictures” (13): “she would surely have had misgivings” (27), “... leaves us feeling that” (28), “it does not seem far-fetched to say” (29), “we can fairly represent” (29), “surely” (33), “presumably” (36). As Christina Rossetti very seldom expressed an outright opinion on those images which began to proliferate during the Victorian age, any reconstruction of her tastes concerning the visual arts, any judgment as to her iconophobia or -philia must remain tentative. Even though she was unique in being the only major poet who grew up “so deeply embedded in an avant-garde visual culture” (28), it seems that her faith induced her to consider that “representational art can only get in the way of th(e) imaginative operation, muddying rather than clarifying” (32). And yet, in their introduction, Owens and Tromans do not hesitate to write that in Rossetti’s life, “literature was the warp and visual art the weft” (12), notably because her works “have inspired – perhaps even haunted – artists since her poetry first began to be published” (9).

Related Material

- "Christina Rossetti: Vision and Verse" (review of the exhibition which this book accompanies)

- Christina Rossetti and the Visual Arts

- John Brett and Christina Rossetti

- 'The Memory of Her Own Childhood" (about Sing-Song)

Source

[Book under review] Owens, Susan, and Nicholas Tromans, eds. Christina Rossetti: Poetry in Art. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018. Hardback, 192 pp., 200 colour / black and white images. ISBN 978-0300234862. £30.

Created 23 January 2019