Dedicated to the memory of Andrea Gayle Holm Allingham: Wife, Mother, Teacher, and Writer (13 April 1949-11 July 2019)

I suppose that no two people, not vicious in themselves, were ever joined together, who had greater difficulty in understanding one another, or who had less in common — Charles Dickens's "Violated Letter," 16 August 1858. [qtd. in Slater, Dickens and Women, 103]

atherine Hogarth, eldest daughter of music critic, Morning

Chronicle editor, and former Edinburgh lawyer George Hogarth (1783-1870), met

young Charles Dickens in the early 1830s in London. Quickly, the Hogarths' regular

visitor became their prospective son-in-law. The two young people got engaged in the spring of 1835. As Michael Slater

remarks in The Oxford Readers's Companion to Dickens, the

letters which the fledgling author of sundry London "Sketches" addressed to "My dearest

Kate" during the period of courtship "show none of the passionate intensity of his

feelings for Maria Beadnell, but instead reveal a relationship based on common interests

and enthusiasms and mutual affection" (153). As her biographer, Lillian Nayder, makes

clear, although Catherine was still a teenager when she met the rising author in her father's

house, she was a well-rounded, well-read young Scot who was Dickens's equal in

social standing, taste, and intellect, and certainly no mere Dickensian ampersand.

atherine Hogarth, eldest daughter of music critic, Morning

Chronicle editor, and former Edinburgh lawyer George Hogarth (1783-1870), met

young Charles Dickens in the early 1830s in London. Quickly, the Hogarths' regular

visitor became their prospective son-in-law. The two young people got engaged in the spring of 1835. As Michael Slater

remarks in The Oxford Readers's Companion to Dickens, the

letters which the fledgling author of sundry London "Sketches" addressed to "My dearest

Kate" during the period of courtship "show none of the passionate intensity of his

feelings for Maria Beadnell, but instead reveal a relationship based on common interests

and enthusiasms and mutual affection" (153). As her biographer, Lillian Nayder, makes

clear, although Catherine was still a teenager when she met the rising author in her father's

house, she was a well-rounded, well-read young Scot who was Dickens's equal in

social standing, taste, and intellect, and certainly no mere Dickensian ampersand.

The daughter and granddaughter of cultured Scotsmen and women — intellectuals, writers, and musicians who highly valued family life — Catherine Hogarth was an animated and well-read nineteen-year-old, a devoted sister and cousin.... For forty-two of her sixty-four years, she lived apart from the famous man who has come to define her, spending her first two decades as Miss Hogarth an her last two as the estranged wife and widow of "the Inimitable." [1]

Early Life: Edinburgh to London, 1816-1834

Catherine Thomson ("Kate") Dickens (née Hogarth; 19 May 1815 – 22 November 1879), the eldest of the ten children of George Hogarth and Georgina Thomson, was born in Edinburgh, then a cultural and literary Mecca justly known as "The Athens of the North." George and Georgina Hogarth, like their eldest daughter, had ten children, including four daughters closely associated with Charles Dickens: Catherine Hogarth (1815), Mary Hogarth (1819), Georgina Hogarth (1827) and Helen Hogarth (1833). Although Catherine's father had studied law and had even been Sir Walter Scott's attorney, he had also studied cello and composition, and had served as joint secretary to the Edinburgh Music Festival. To pursue his second career as a journalist with a specialty in music criticism, he moved the family briefly to London, then in 1831 to Exeter to edit the Western Luminary, and then to Halifax in 1832 to edit The Halifax Guardian. Although slightly Bohemian, George was a supporter of the Tories, whom he regarded as a bulwark against a French-style revolution. Thus, he opposed the very parliamentary and electoral reforms that young Liberals such as Dickens were advocating in the early 1830s. Finally the Hogarths arrived back in London in 1834, settling into a large house with a garden on the Fulham Road so that George could take up the post of musical and dramatic critic for the Morning Chronicle before becoming editor of the Evening Chronicle in 1835. In that capacity, he solicited twenty-three-year-old Dickens to write sketches of London life and middle-class characters for the new, thrice-weekly periodical.

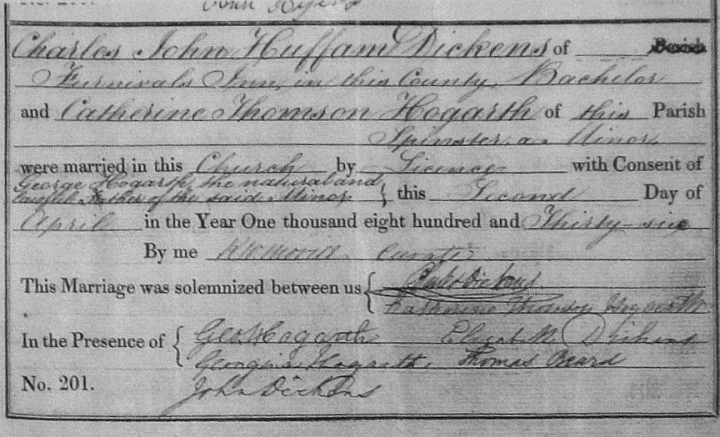

Copy of the couple's marriage certificate at St Luke's Church Chelsea.

Peter Ackroyd quotes a description of Catherine at this time as being "a pretty little woman, plump and fresh-coloured, with the large, heavy-lidded blue eyes so much admired by men. The nose was slightly retrouué, the forehead good, mouth small, round red-lipped with a genial smiling expression of countenance, notwithstanding the sleepy look of the slow-moving eyes" (164). Whereas Maria Beadnell, Dickens's previous romantic attachment, had been flirtatious and capricious, Catherine was uniformly cheerful and sweet-natured; Hans Christian Anderson, a houseguest of the Dickenses in 1847, admired in her "a certain womanly repose." After an engagement of almost two years, she married Charles Dickens on 2 April 1836 in St. Luke's Church, Chelsea, and enjoyed a brief honeymoon at Chalk, near Chatham in Kent. They set up housekeeping where Dickens had had bachelor rooms, at Furnival's Inn, Bloomsbury, until 1837, when they moved to a commodious townhouse at 48 Doughty Street in Bloomsbury, now The Dickens House Museum.

The Early Years of Her Marriage

Catherine's younger sister, Mary Scott Hogarth, came with Catherine to Dickens's Doughty Street home to support to her newly married sister and brother-in-law. Indeed, it was customary for the unwed younger sister of a new wife to live with and help a newly married couple, especially in the early years of the marriage when the couple were coping with infant care. Both Dickens and his wife were shocked by Mary's sudden death after an evening at St. James's Theatre, on 7 May 1837. In December 1839 the couple moved from this house redolent of memories of Mary to 1 Devonshire Terrace, York Gate, Regent's Park, which remained their home until 1851, except for a period of about a year (1844-45) when they lived in Genoa. With more than a dozen rooms, Devonshire Terrace was decidedly upper-middle class: it had a library, a drawing room, a dining room, several bedrooms, a day nursery and a night nursery, sufficient for their four children.

Catherine's younger sister, Georgina Hogarth, became a member of the Dickens household in 1842 when Charles and Catherine sailed to America so that she could look after the Dickens children. Meanwhile, the Dickenses were under close scrutiny through the 1842 American reading tour. Catherine was consistently a credit to her husband throughout the American tour, winning American intellectuals and political figures with her charm, intelligent conversation, and pleasant manner. Despite homesickness and yearning to see her children, she acted alongside her husband on stage with members of the garrison at the Queen's Theatre in Montreal, Quebec. While her husband starred in no less than three comic roles, she merely played the part of an ingénue Amy Templeton in John Poole's one-act farce Deaf as a Post. However, her devoted husband gushingly pronounced her having enacted her minor role "devilish well" (26 May 1842).

The Strain of the 1850s on Her Marriage

In 1851, writing under the pseudonym "Lady Maria Clutterbuck," Catherine published a culinary preparation guide, What Shall we Have for Dinner? Satisfactorily Answered by Numerous Bills of Fare for from Two to Eighteen Persons. Catherine, with considerable experience as a hostess, suggested menus for substantial meals of varying complexity together with a few recipes. By 1860 it had gone through several editions. Also in 1851, after the death of her eight-month-old daughter Dora, Catherine experienced a nervous breakdown. By the time that their tenth and final child, Edward, was born in 1852, Dickens was increasingly unsettled and dissatisfied, despite affectionate letters he wrote Catherine during his two-month tour of Italy with Wilkie Collins and Augustus Egg in the autumn of 1853. During the period of the early 1850s Catherine was becoming heavier and more matronly in appearance, and her middle-aged husband increasingly restless.

Over the next five years, Dickens critcized Catherine as an incompetent mother and housekeeper, and blamed her for the births of their ten children, an unreasonable charge probably prompted by his financial concerns. The turning=point in their marital relations seems to have occurred in January 1854. Charles had hoped to have no more children after the birth of their fourth son, Walter, so, to ensure that there would be no more children, he had their sleeping arrangement altered by having a bookshelf placed between them. By the time that Dickens had purchased Gad's Hill Place in Kent in 1856 and moved the family there, the marriage was probably doomed. Dickens, having starred as Richard Warder in Collins's Arctic melodrama The Frozen Deep at the converted theatre in their residence from 1851, Tavistock House, in January 1856, decided to take the show on the road in support of the charity "The Guild of Literature and Art." The decision meant that amateur actresses would no longer be adequate for the production. For the Manchester performance, accordingly, he contracted three professional actresses in August 1857: Ellen and Maria Ternan and their mother took the main female roles. Matters came to a head for Charles and Catherine in the spring of 1858; the marital breakup seems to have been triggered by the gift of an inscribed bracelet for the nineteen-year-old Ellen. He insisted that their relationship was purely platonic, and that Catherine should pay a social call upon the Ternans to demonstrate that his relationship with the young actress (contrary to rumours already circulating) posed no danger to the marriage. Catherine's mother and sister Helen now began spreading rumours about Dickens's infidelity with Ellen.

In May 1858, after Catherine accidentally received the bracelet meant for Ellen, Dickens' increasingly found himself having defend himself against imputations of infidelity, which he denied vociferously in person and in the popular press. Even though a divorce might have been possible, it would have far too expensive — and too public, hardly conducive to the reputation of the editor of a family magazine. He and Catherine therefore opted for a separate maintenance. In spite of Angela Burdett Coutts's attempts at a reconciliation for Katey's wedding in 1860, he adamantly refused.

The Later Years: A Virtual and then a Real Widow

Although the pair barely corresponded afterwards, Catherine did write to her estranged husband after the Staplehurst railway accident on 24 June 1865, inquiring as to his health. He replied curtly, but signed himself "Affectionately." The other occasion was on the eve of his second American reading tour in November 1867. She received the following reply, the last words she would ever read from her husband:

My dear Catherine

I am glad to receive your letter, and to accept and reciprocate your good wishes. Severely hard work lies before me; but that is not a new thing in my life, and I am content to go my way and do it.

Affectionately yours

Charles Dickens [qtd. in Slater 154]

Slater believes that, despite his resentful treatment of her, Catherine never ceased to love her husband. She, of course, could not help following his public career, including his triumphant reading tours abroad and throughout the United Kingdom. She was, moreover, consoled by Georgina's continued presence in the Dickens household, as her being at Gad's Hill assured Catherine that a sympathetic aunt was watching over her children. When she was dying of cancer in 1879, nearly ten years after her husband's much publicized funeral in Westminster Abbey, Catherine gave the collection of letters from Dickens to her daughter Kate, telling her to "Give these to the British Museum — that the world may know he loved me once" (cited in Slater, p. 159). Catherine Dickens died at her home on Gloucester Crescent on the morning of 21 November 1879, and was buried in Highgate Cemetery, London, in the same grave as her infant daughter Dora, who had died eighteen years earlier.

The Will of Catherine Thomson ("Kate") Dickens (née Hogarth

Much has been made of the will. Despite her receiving an allowance of £600 a year, Catherine had no significant property to bequeath to her family, but the numerous treasured keepsakes that she left to her surviving children imply her strong emotional attachment to them all:

To my daughter Katherine Perugini my turquoise snake bracelet pearl broach and earrings The story card basket brought to me by my Charles [her eldest son] from China. The Sketch by Maclise of Charles, Mary, Katherine and Walter when children The case of various stuffed birds given me by Sydney and my Tortoise shell card case To my son Frank the gold watch and chain with locket attached which formerly belonged to Sydney The photograph of Katherine in red velvet and gilt frame ... To my son Alfred my silver sugar basin with lid and spoon, the small agate vase with cupids ... To my son Edward the gold locket formerly worn by his father containing portraits of Mary and Katherine, the pair of small Candlesticks given me by Sydney.... [qtd. in Slater 159, from a typescript of the will at The Dickens House Museum, London]

Other items, according to Nayder, included a bronze inkstand brought from Rome by Sydney (for grandson Charles Walter Dickens), an ivory elephant figurine with houdah sent by Walter Dickens from India, and a Japanese cabinet for granddaughter Mary Angela Dickens. Granted, the value of these personal treasures was nothing compared to the copyrights that her husband bequeathed in equal shares to all his children in 1870, but unlike Charles she sought to include all the important people in her life in her 1878 will. Whereas he had named only three of his children (Charley, Mamie, and Henry), had privileged some children over others, and had left an estate valued at ninety thousand pounds, she left the bulk of her estate to her sister Helen, but strove to remember all of her relatives and close friends, as well as her servants at Gloucester Crescent, naming all four as recipients of brooches, sleeve studs, a photograph; one even received Catherine's sewing machine. As Nayder concludes,

Catherine's will, unlike her husband's, acknowledges each of the children, regardless of success or failure. Aiming above all else to be loving, inclusive, and even-handed, she organizes her bequests objectively, according to birth order. Gender, marital status, merits and demerits: these play no part in her testamentary scheme. Insofar as Catherine draws moral distinctions in her will, she does so implicitly and only in regard to the Hogarths: not by what she leaves Georgina, an enamel snake ring, but by what she doesn't leave her — any mementoes or relics from the Hogarth family. [336]

Related Materials

- A Chronology of Dickens's Life

- Major Biographies of Dickens — a Critical Overview

- Mary Scott Hogarth, 1820-1837: Dickens's Beloved Sister-in-Law and Inspiration

- The Children of Charles Dickens and Catherine Hogarth Dickens, 1837-52

- Where the Dickens: A Chronology of the Various Residences of Charles Dickens, 1812-1870

- Dickens's affair with Ellen Lawless Ternan

- The Invisible Woman — A film about Charles Dickens and Nell Ternan

- Dickens' Professional Career [Chapter 1 of E. D. H. Johnson's Charles Dickens: An Introduction to His Novels]

- Dickens's 1842 Reading Tour: Launching the Copyright Question in Tempestuous Seas

- Divorce in the Victorian Period

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1999.

Nayder, Lillian. The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth. Ithaca, New York: Cornell U. P., 2011.

Slater, Michael. "Dickens, Catherine Hogarth." The Oxford Readers's Companion to Dickens, ed. Schlicke, Paul. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 153-157.

Slater, Michael. Dickens and Women. London and Melbourne: J. M. Dent, 1983.

Created 1 September 2019