This review is reproduced here by kind permission of the Historians of British Art, who first published it in their 2009 Summer Newsletter. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee, who has also added captions and links. Click on the images for larger pictures and more information.

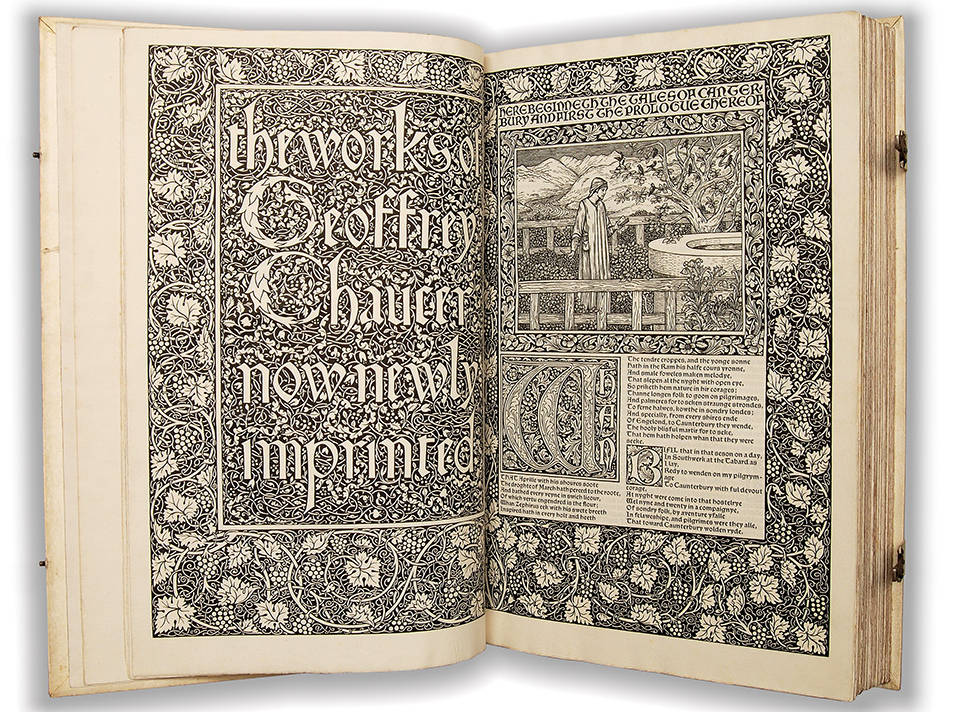

Caroline Arscott, Senior Lecturer at the Courtauld Institute of Art, continues her exploration of Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and William Morris (1834-1896) with this examination of what she calls "the interconnections in theme, allusion and formal strategy between Burne-Jones's paintings and the designs of Morris" (9). The reader is very appropriately reminded that their collaboration started very early in their lives, with their work for the Oxford Union in 1857, and culminated with the Kelmscott Chaucer "completed just before Morris's death in 1896" (16-17).

Contrary to so many "coffee-table books" on the Pre-Raphaelites and their friends which seem to flood the market nowadays, the text is not a thinly-disguised pretext for the (superb) reproductions which constitute an undeniable attraction of the large-size volume. Far from it: the text proper is extremely dense, often hard to follow because of the complexity and variety of the strands pursued, and sometimes difficult to agree with — as it should be in any work with an innovative ambition. One characteristic of the cautious scholar is that he is wary of audacious rapprochements.

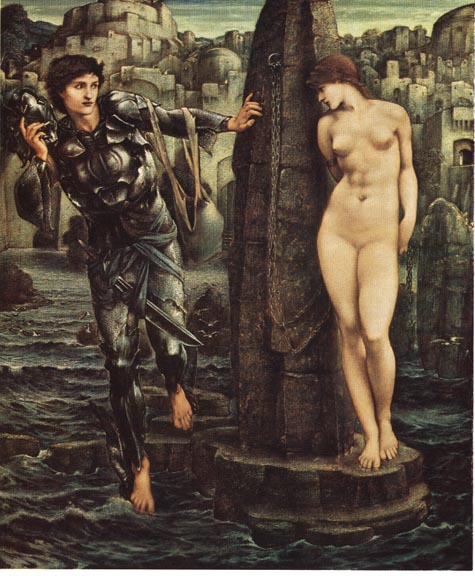

The Rock of Doom by Burne-Jones (Number 6 in the Perseus Cycle, 1885-88), with its "representation of bare skin v. armour."

Comparing works in different media can be more confusing than it is enlightening — at least this is what this reviewer's generation was taught. Yet this is precisely what Dr Arscott undertakes to do, drawing parallels not only between works in different media by Burne-Jones and William Morris, but also between these works and a wide variety of images — the farthest removed from the (late nineteenth-century) Zeitgeist, which according to older conventions of art interpretation provided the only legitimate foundation for such comparisons, being a still of Arnold Schwarzenegger in "The Terminator" (1984; fig.26). Naturally, there is a justification for these forays into "extraneous" territory: in this instance, the author is exploring the theme of "the man-machine," in connection with Burne-Jones's fascination for historic armour and his work on the (male) body in action. Likewise, the illustrated discussion of books treating of the introduction of breech-loading guns and new kinds of cartridges — though not infringing the chronological framework — might be seen as taking the reader too far from the theme announced in the title of the book: but again, Dr Arscott has the last word, explaining that "The metaphors and adjectives that are applied to the new guns and projectiles can indeed be used to summon up a hero's body for the modern day" (77). The rest of the chapter (Chapter 3) is devoted to a masterly exploration of the representation of bare skin v. armour in Burne-Jones's works, notably his various renderings of the story of Perseus.

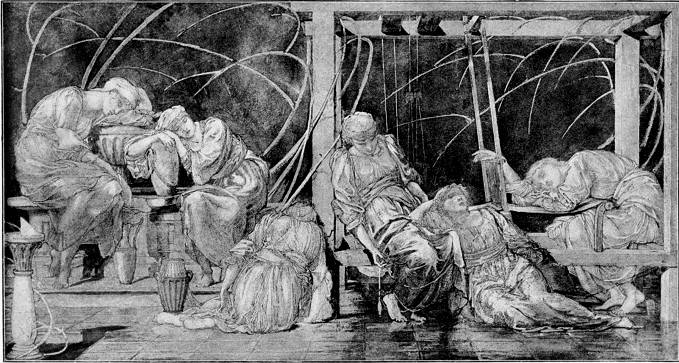

Left: Study for The Garden Court in "The Legend of the Briar Rose," by Burne-Jones, from the 1893 Magazine of Art. Right: Lea designed by Morris (1885).

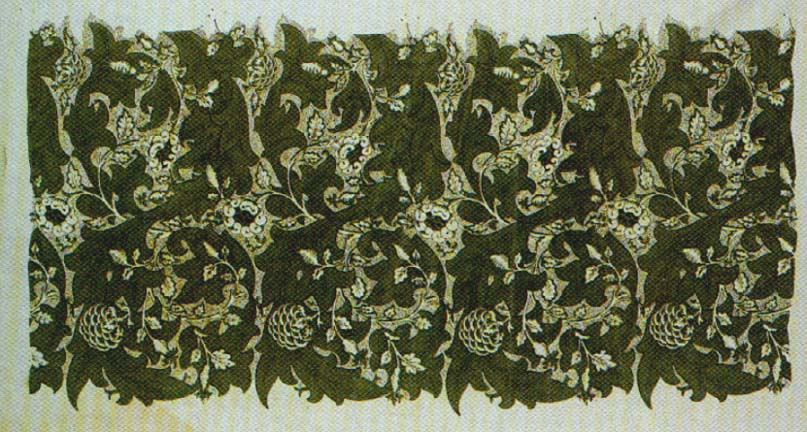

The skin, in all the acceptations of the word — literal as well as figurative, biological (fig.58) as well as mental — provides in fact the central element in the book, with the unifying idea that Burne-Jones's work is associated with the external (epidermal) aspect while that of William Morris has more to do with the internal (dermal) side — things of course being more complicated. For instance, Burne-Jones's preoccupation with the outer skin in Chapter 3 is followed by a discussion of William Morris in terms of "Heart and Flesh" (Chapter 4). And one returns to the epidermal with Chapter 5, devoted to Burne-Jones's Briar Rose series. The "potential for beauty in pattern embedded in flesh" (127), as in tattooed bodies, is examined in relation to Morris's works in the next chapter, with many suggested or at least potential rapprochements between the nineteenth-century illustrations and Morris designs reproduced — but also in Chapter 7, which notably discusses Burne-Jones's fascination with tattooed people as "exhibited" in 1880s and 1890s London. In Chapter 8 ("Morris: The River"), the above/under duality of the human skin is extended to the surface of the water, leading to an insightful commentary on Morris's 1883-1887 series of patterns named after rivers (Avon, Lea, etc).

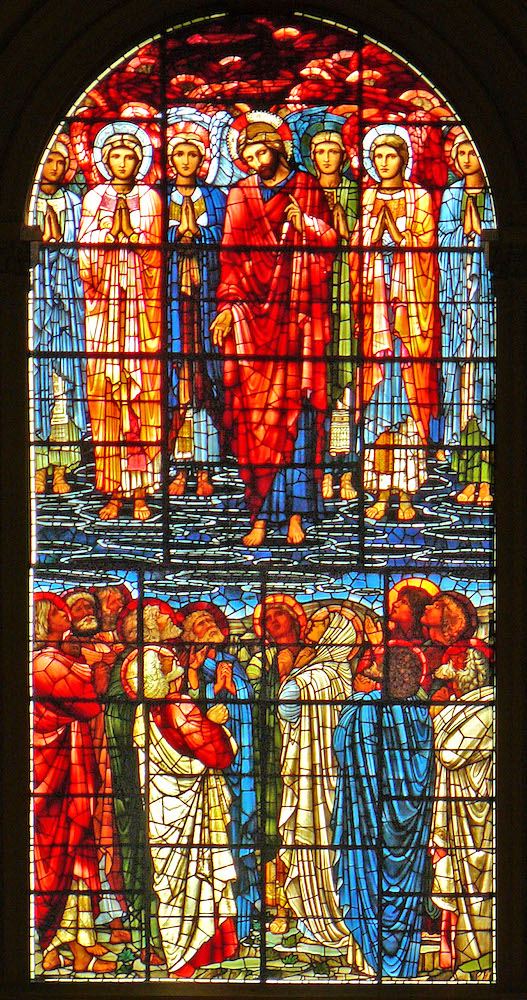

East windows of St Philip's Cathedral, Birmingham, with stained glass designed by Burne-Jones and executed by Morris & Co.: Left to right: (a) The Nativity (1887-88). (b) Detail of The Nativity. (c) The Ascension (1885).

The last chapter attempts to reassemble all the threads again, concentrating on the two friends' common work in stained glass for the Church of St. Philip in Birmingham, with another allusion to the theme of organic flesh rendered by inorganic glass (217). The only real criticism that one may level at this very ambitious monograph is that it ends abruptly with this chapter, with no general conclusion.

It is evidently impossible in a short review to do justice to all the challenging insights which the book contains. Contextualisation is of course mandatory when seriously discussing any oeuvre: what makes the strength of Dr Arscott's volume, arguably, is that she does this work of contextualization from so many new perspectives. Not everybody will agree with them — but this is the rule of the game. On the other hand, everybody will agree that Interlacings constitutes a capital addition to Burne-Jones and William Morris Studies. It goes without saying that it should be in all Art School and British Studies libraries: besides the impeccable, up-to-date Bibliography, advanced students and colleagues will particularly appreciate the copious (twenty-five pages on double columns), most informative Notes which often open new vistas in themselves.

The Kelmscott Chaucer, on which Burne-Jones and Morris collaborated (published 1896).

Related Material

- Pre-Raphaelite Approaches to Ut Pictura Poesis: Sister Arts or Sibling Rivalry? (Morris and Burne-Jones)

- Morris and the Kelmscott Press

Source

Arscott, Caroline. William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones: Interlacings. Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008. 259 pages. ISBN: 0300140932 (hbk.) / ISBN: 9780300140934.

Last modified 3 February 2014