We are most grateful to be able to reproduce here material from Jane Rupert's edition of Letters of a Distinguished Physician from the Royal Tour of the British North American Colonies 1860 written by Henry Wentworth Acland. The whole edition is available on the web by clicking here.

n addition to his passion for science and medicine, Henry Wentworth Acland, also took deep delight in art. From mid-century at Oxford he was a curator of the University Galleries, later merged with the Ashmolean Museum, which had acquired a large collection of drawings by Raphael and Michaelangelo in 1841. At the university he exercised an instrumentality in the domain of art similar to the instrumentality he exercised in the physical sciences and medicine. As an advocate for the introduction of Fine Art as a new discipline at Oxford, he succeeded in persuading John Ruskin, the century's foremost art critic, to become the first Slade Professor of Fine Art in 1869. Artists were also among the many guests in the Aclands' home. In 1855 when Pre-Raphaelite artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, Holman Hunt, and William Morris were painting tempera frescos in the university's debating-room, they were the Aclands' constant visitors. Acland also attended to them as physician, prescribing a winter abroad to slender, copper-haired Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti's laudanum-addicted model. When Siddal gave Acland one of her own paintings in gratitude, it became part of his own growing and eclectic collection of art that came to include many of the nineteenth-century's leading artists.

Drawing and painting were also Acland's recreation. Amid the multiple demands of his busy professional life, on holidays and travels he kept a sketch book at hand, finding in art a restoration of overtaxed faculties in an attunement of sense, mind, hand, and heart with the landscapes, seascapes, and portraits he painted. He first began cultivating this artistic sensibility during the eighteen months spent in 1837-39 in the Mediterranean aboard a British naval ship after a leading physician and family friend prescribed rest and sea air for his violent headaches. Here in the Mediterranean light, he observed colour and the play of shadows while sketching the Acropolis and sites from antiquity in Turkey and at Tunis.

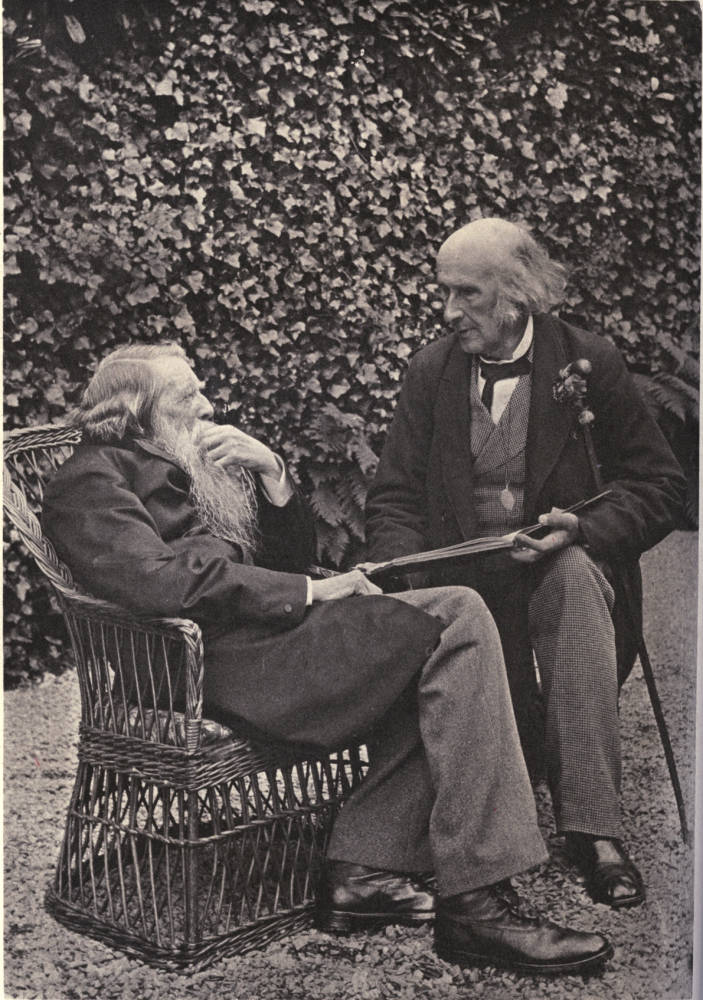

John Ruskin and Sir Henry Acland, taken by Miss Acland, 1 August 1893.

In his own artwork, Acland also benefited from a warm, life-long friendship with Ruskin, his fellow student at Christ Church. In a letter in 1841, Ruskin expressed surprise at how little Acland knew about basic techniques in the use of colour and the depiction of shadows. He advised him about the application of yellow ochre mixed with Indian red to make gray for shadows and, in accordance with his aesthetic theory that the direct observation of nature was the artist's starting-point, advised him to investigate the principles of art through his personal observation of colours and shadows: to ask, for example, how shadows change as the sun moves and why they have such a form or such a depth.

In 1853, Acland spent a week sketching in the Scottish Highlands in the company of Ruskin, Ruskin's wife, and the painter, John Everett Millais. Acland held the canvas as Millais painted the wild grandeur of a mountain stream cascading through tough metamorphic rock by a dark, overhanging bank sprinkled with common flowers like butterwort and violets. This work, to which Millais later added the figure of Ruskin contemplating the scene, reflects Ruskin's rejection of any mannerist use of scenery and asserts the Wordsworthian sense of nature as the object of inspired, ontological contemplation. In 1869 the Portrait of Ruskin, at Glenfinlas, now considered a landmark in British art, became part of Acland's collection, a gift from Ruskin.

John Ruskin by Millais, 1853-54.

In 1854-55, Acland also corresponded with the artist, Samuel Palmer. They discussed the best sites for painting the westerly sun setting into the sea, such as Margate, favoured by J.M.W. Turner. Acland attempted to arrange a week of watercolour instruction with Palmer whose early ethereal landscapes influenced by William Blake are much admired today. However, perhaps the most fundamental influence on Acland's work was the technique that he had learned as a youth from the Principles of Landscape Drawing, 1816-1821 by John Varley. A friend of the artist, William Blake, Varley outlined four stages in painting landscapes, each of which could stand on its own as complete in itself. The first stage involved a quick pencil sketch recording in a few lines the impression of a landscape. In the second stage, indelible brown ink was added rapidly. In the sepia tones found in some of Acland's pictures we find the third stage which involved laying in all the shadows very broadly with what was called Cologne earth, a colour made from brown coal. In the final stage, such as in Acland's compelling portrait of a Mi'kmaq woman painted in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, colours were added in broad, flat washes completed with white for points of special brilliance.

"Southwest" on the Nashwaaksis River, New Brunswick. 5 August 1860.

The 250 sketches and paintings of places and people that Acland worked in this way during the tour of North America both complement and supplement his letters. Acland painted this Maliseet paddler called Savisse or Southwest during a canoe excursion with the Prince of Wales and his two young equerries on the Nashwaaksis (little Nashwaak), a stream running through the Maliseet settlement located across the St John River from Government House. On two occasions, Acland received advice from the artist and watercolour teacher, Samuel Palmer, on mixing pigments used in finished paintings like Southwest. In 1855 Palmer described a recipe for washed gambage using yellow pigment from an evergreen resin to produce a semi-opaque green tint. In 1866, Palmer sent Acland a special recipe for making opaque white paint that William Blake claimed to have received from St Joseph in a dream vision. Effective in setting off a finished watercolour painting, the paint was made from white pigment mixed with warm water, glue, and creosote to give it the right consistency.

Other Material Relating to Dr Acland

- Dr Henry Wentworth Acland: A Brief Biography

- Ottawa as Provincial Capital of Canada in 1860

- Canada's Indigenous Peoples

- The Timber Industry in Canada

- Victoria Bridge, Montreal

Bibliography

Acland, Henry Wentworth. "Introduction and Letter 4: New Brunswick" in Letters of a Distinguished Physician from the Royal Tour of the British North American Colonies 1860, ed. Jane Rupert, web janerupert.ca

Acland, H.W., and John Ruskin. The Oxford Museum. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1859.

Atlay, J.B. Sir Henry Wentworth Acland. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1903.

Created 3 July 2023