uskin's return to Turner at the end of Modern Painters produced a series of readings unlike anything that he had done before. The painter he had celebrated as an angel of divine revelation now brought a different message. His old master in the science of aspects had become the master of a new art: he reinterpretation of traditional symbolic language. This revision of language, Ruskin came to feel, was the proper work of the imaginative artist—and also of the critic. Ruskin changed his methods of reading symbolic art and his conception of his own critical role, particularly of the critic's relation to the artistic tradition he interprets. His final word on Turner was also a final word on the author of Modern Painters and an introduction to the author of Unto This Last and The Queen of the Air. Behind his new understanding of Turner, of reading, and of the links between art and criticism, we can trace a third model for approaching the language of art: historical philology.

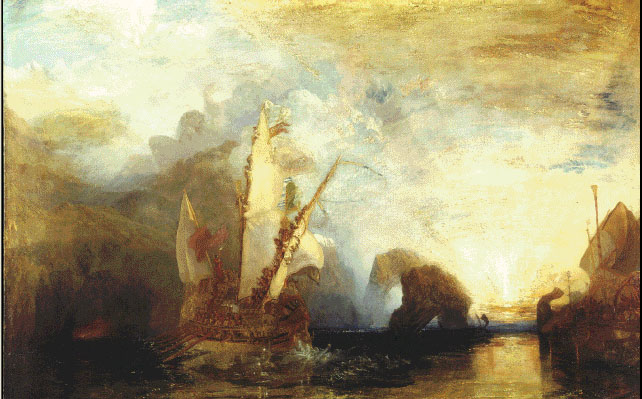

he development in Turner's painting style, Ruskin insisted as early as Modern Painters I, was his increasing use of color rather than chiaroscuro to suggest space and form (3.244-47). The pictures Ruskin chose to explicate in Modern Painters V allow him, at least initially, to present the change from cloudy chiaroscuro to cloudy color as a union of romantic technique with biblical and natural symbolism. He sets out to show that Turner, too, was aware that the change in technique was a triumph of moral and spiritual as well as artistic dimensions for the artist-hero—that Turner, too, looked on cloudy [232/233] color as the natural symbolic language of divinity. If Ruskin's readings are right, Turner dramatizes his own shift from chiaroscuro to color as the victory, first, of the god of light over a terrifying dragon of darkness (Apollo and Python, and later of the Homeric hero Ulysses over the smoky volcanic one-eyed monster (Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus, a victory again marked by the presence of Apollo as sun-god.1

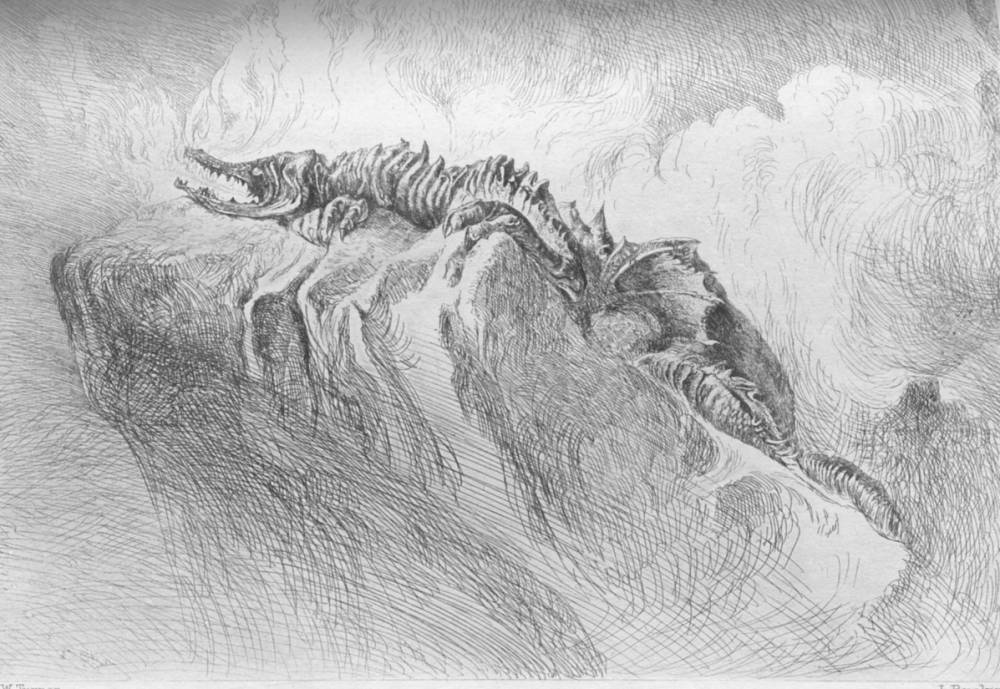

To make his point, Ruskin begins with the earlier Hesperides, illustrating Turner's chiaroscuro style.2 Ruskin's reading stresses the gloom of both tone and message in the painting. The garden's guardian dragon, which Ruskin identifies mythologically, using Hesiod, with storm clouds and consuming passions, appears as the literal and the figurative source of the discord that will finally burn Troy.3

The Goddess of Discord Choosing the Apple of Contention in the Garden of the Hesperides by J. M. W. Turner. [Click on this image to enlarge it.]

From the dragon's glacial, cloud-enveloped shape, stretched across the cliffs in the background, spread an overhanging gloom and the dark river that divides the garden and threatens to overwhelm its nymphs, the Hesperides. Ruskin identifies them as Aeglé (Brightness), Erytheia (Blushing), and Arethusa (the Ministering); in Turner's naturalistic terms, "light in the midst of a cloud," or sunset color. Hesperides suggests to Ruskin that for Turner cloudy gloom can function symbolically to indicate the inevitable consequences of consuming passions —a dark message coming from a terrible divinity, the ambiguous guardian dragon, who seems to be himself both source and punisher of evil.

Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus by J. M. W. Turner. [Click on this image to enlarge it.]

In the second picture Ruskin discusses, the bright figure of Apollo slays a vaporous serpent who writhes downward into a pool of darkness. Ruskin points to the color in the clouds behind Apollo as a new element in Turner's work, a harbinger of the colored clouds that increasingly dominate his later compositions. He notes also that the association between Apollo and colored clouds occurs again in Ulysses, another painting about a heroic victory over a monster of darkness. (7.411-12).

Apollo and Python by J. M. W. Turner. [Click on this image to enlarge it.]

Given the long traditions connecting Apollo with wisdom, purity, and healing, and his serpentine foe with physical and moral corruption, Ruskin concludes that Turner has associated his own artistic mastery of color and suggestive technique with the spiritual and moral victories embodied in the myths. And Ruskin finds Turner's association justified by the biblical symbolism of rainbow-colored clouds in Genesis 9:13. [233/234] The cloud, or firmament, as we have seen, signifies the ministration of the heavens to man. That ministration may be in judgment or mercy—in the lightning, or the dew. But the bow, or colour of the cloud, signifies always mercy, the sparing of life; such ministry of the heaven as shall feed and prolong life. And as the sunlight, undivided, is the type of the wisdom and righteousness of God, so divided, and softened into colour by means of the firmamental ministry, fitted to every need of man, as to every delight, and becoming one chief source of human beauty, by being made part of the flesh of man;—thus divided, the sunlight is the type of the wisdom of God, becoming sanctification and redemption. Various in work—various in beauty —various in power. Colour is, therefore, in brief terms, the type of love. (7.418-19)

This passage recalls those earlier portions of Modern Painters IV and V that we have already examined. Ruskin invokes modern theories of light and perception to give a new, naturalistic basis to Augustine's reading of the created heavens. Those heavens, as atmosphere or clouds, act as a prism to divide sunlight into varied color. Ruskin translates Augustine's emphasis on the varied forms of creation into terms that suit romantic, and particularly Turnerian, art: the beauty of the visible divine creation is the varied color of space and cloud. Color is then the type of a merciful, redemptive divine symbolic language; and clouds, or cloudy and suggestive technique, are the means by which both color and significance are produced. In Apollo, the purifying significance of the colored cloud is indicated through a naturalistic rendering of myth, just as in Hesperidcs naturalized mythology indicated a terrifying divinity speaking through the dark storm cloud. In these two paintings, as in Salisbury and Stonehenge, Turner's language and message coincide with scripture and nature. The triumph of light and colored cloud is the triumph of a loving divinity as it ministers—and speaks—to men.

Here, then, is the framework for a conclusion to Modern Painters. The hyperbolic description of Turner in Modern Painters I can, after all, be justified. The artist who turned from gloomy to colored cloud took up God's language to announce that the natural world did testify to the victory of light and love over monstrous powers of darkness and discord. Ruskin's reading of Apollo completes the metaphorical link he set out to create between Turner's brilliant art of clouds and the cloudy revelation of nature and the Bible. [234/235]

But Ruskin's reading does not end here. Out of the dying Python, he points out, crawls a small serpent, identical with the small snakes that Turner repeatedly uses to signify the presence of some ominous evil in an otherwise paradisical landscape. In The Bay of Baiae, the serpent is a reminder that Apollo's gift of all-but-immortal life to the beautiful Sibyl was flawed—he did not grant her immortal youth.

The Golden Bough by J. M. W. Turner. [Click on this image to enlarge it.]

In the serpent is a reminder of the dark powers the hero Aeneas—who is shown arriving at his promised paradise, Italy, and being greeted by the same beautiful Sibyl—must confront when she conducts him on a Ulyssean journey to the underworld. Adding up the evidence of these pictures, Ruskin laments "Alas, for Turner! ... In the midst of all the power and beauty of nature, he still saw this death-worm writhing among the weeds . . . He was without hope" (7.420-21). In the space of a few paragraphs, Ruskin completely reverses the reading toward which he seemed to be moving. Turner's color cannot, Ruskin goes on, be read as the type of a beneficent and purifying love, a divine promise manifested in the beauty of the natural world. Whatever symbolic associations the colored clouds may carry are, he concludes, simultaneously questioned by the continued power of darkness and death suggested in the paintings. For Ruskin's Turner the Hesperid Aeglé, sunset color, is literally a child of Night, sister of "Censure, and Sorrow,—and the Destinies" 7.421). The rose-tinted clouds of Turner's Apollo may very well anticipate his new use of color, but if so they anticipate not only his association of brilliantly colored landscapes with the triumph of beauty and ove, but also his association of that beauty with delusion, betrayed lopes, and eventual death.4 The central "fallacy of hope" (Turner's title for his poetry) for Turner, Ruskin came to believe, was the fallaious promise of light and color themselves—the subject of Apollo, The Bay of Balae, and the terrifying The Angel Standing in the Sun. This is ie revised interpretation of Turnerian cloudy symbolism with which Ruskin actually concludes Modern Painters. "What, for us, his work et may be, I know not. But let not the real nature of it be misunderood any more" (7.421).

The "Alas, for Turner" is an "Alas" for Ruskin too. In the concluding chapters he largely shares what he reads as Turner's highly pessimistic vision. Turner's paintings seem ironically to reverse the biblical or [235/236] Christian visions he once thought they so gloriously confirmed. This sense of ironic reversal marks Ruskin's own view of what happens to traditional symbols used to express contemporary values. The structure of the Apollo chapter, where the reading turns completely around on a single detail, is one example of a pattern of shocking or ironic about-face which Ruskin uses repeatedly in his social criticism from The Stones of Venice on—here applied for the first time to Turner.5 Turner has, in a sense, become Ruskin's ally as much as Ins subject in these pages, his ally as a contemporary social and cultural critic.

I shall come back to Ruskin's new methods of reading, but I want to look first at some passages where what is happening is not so much interpretation as assimilation. In these passages, at the ends of chapters after the critical work on Turner has been completed, Ruskin draws on Turner where he would once have used the Bible. Or rather, Ruskin's figurative language is both biblical (and Greek) and Turnerian; but it is Turner's reinterpretation of traditional symbolism, frequently carrying with it an ironic sense of distance and change, which Ruskin now adapts to his own uses. His chapter on Hesperides ends with an extended allusion to Turner's painting by means of which Ruskin expresses his own equally pessimistic thoughts—his sense of the disintegration of modern faith and the destructive influence of modern work.

Quivi Trovammo — The dragon from Turner's "Garden of the Hesperides" by John Ruskin. [Click on this image to enlarge it.]

In a sequence of contrasts (not a reconstruction of historical influence) Ruskin juxtaposes, first, Perugino's paradises of clear light and color, presided over by Madonnas, with the modern British "paradise of smoke" in Hesperides, presided over by a gloom-spreading dragon wrapped in a sulfurous halo. The second juxtaposition, also Ruskin's and not Turner's, puts Dürer's celebration of the hopeful strength of sorrowful labor, his Melancholia "with eagle's wings, and . . . crowned with fair leafage of spring" (7.314), next to a modern celebration of the spirit of work, for which Ruskin again takes Turner's gloomy false guardian, the dragon "crowned with fire, and with the wings of the bat" (7.408). In Ruskin's paragraphs Turner's dragon is used as an emblem of consuming as opposed to productive labor, a destructive deity—the perversion of Carlylean work-as-worship which has usurped all other faiths in contemporary England. This concluding passage, where Turner's painting has become part of Ruskin's own symbolic vocabulary, should not be confused with Ruskin's reading of [236/237] Turner's painting; it is instead a deliberate extension of interpretation for the purposes of cultural criticism.

The Angel Standing in the Sun by J. M. W. Turner. [Click on this image to enlarge it.]

The most important of Ruskin's appropriations of Turner's symbolism in Modern Painters V is his use of The Angel Standing in the Sun in the concluding paragraphs of "The Two Boyhoods." I want to look at it in some detail because it provides such striking evidence of Ruskin's new understanding not only of Turner but of his own role as a critic interpreting and reusing the symbolic language of art. The angel in Turner's painting may well be the artist himself; the painting may be Turner's ironic response to the criticism of his late works, including both hostile comments on his blinding color (the figures in the foreground flee the angel standing in the midst of what is indeed a blinding yellow-white sun) and Ruskin's own hyperbolic praise of Turner as an angelic prophet of revelation through sun, cloud, and rainbow.6 Ruskin, at any rate, seems to take the painting as an accurate emblem of Turner's vision. His allusion to it in Modern Painters V indicates that he now believes that that vision can in no way be equated with the ecstatic revelation of God's beautiful world for which he had once praised Turner.

Ruskin's reference to the artist-angel standing in the sun depends in part on an earlier chapter, "The Dark Mirror" (the first chapter of his concluding section on symbolic meaning in landscape art). The dark mirror of the title is the human imagination, as it had been in the discussion of grotesque symbolism in The Stones of Venice. Mirror and cloud are cognate metaphors; both transmit light from a source outside themselves to viewers, but with some alteration of the transmitted light (dimming, distorting, dividing, refracting, reflecting). In the earlier work the action of the mind-mirror was closely parallel to the action of the created and written word, the cloud of Modern Painters IV.

Most men's minds are dim mirrors, in which all truth is seen, as St. Paul tells us, darkly ... so that if we do not sweep the mist laboriously away, it will take no image. But, even so far as we are able to do this, we have still the distortion to fear . . . And the fallen human soul, at its best, must be as a diminishing glass, and that a broken one, to the mighty truths of the universe round it ... so far as the truth ... is narrowed and broken by the inconsistencies [237/238] of the human capacity, it becomes grotesque; and it would seem to be rare that any very exalted truth should be impressed on the imagination without some grotesqueness; in its aspect, proportioned to the degree of diminution of breadth in the grasp which is given of it. [11.180-81]

In Modern Painters III Ruskin extended the dimmed and distorted grotesque imagery to include "nearly the whole range of symbolical and allegorical art and painting" (5.132).

Despite the "inconsistencies of the human capacity," Ruskin was confident, in Stones and Modern Painters III, that the mirror-mind could convey sacred truth (5.134). Grotesque symbolism could be read. As he explained in Stones, the mist (associated both with obscuring "passions of the heart" and with an equally obscuring "dulness of heart") we can sweep laboriously away while we can "allow for the distortion of an image" (11.179-81). Interpreting symbolic vision in art was not only parallel to interpreting the created and written word, but dependent on it: holding fast to the Bible as revealed truth we can gauge the extent of the distortion in imaginative vision and allow for it in our reading. In Modern Painters V, however, the dark mirror of the human mind is our only access to sacred light.

"But this poor miserable Me! [Ruskin's imaginary reader objects] Is this, then, all the book I have got to read about God in?" Yes, truly so. No other book, nor fragment of book, than that, will you ever find; no velvet-bound missal, nor frankincensed manuscript;—nothing hieroglyphic nor cuneiform; papyrus and pyramid are alike silent on this matter;—nothing in the clouds above, nor in the earth beneath. That flesh-bound volume is the only revelation that is, that was, or that can be. In that is the image of God painted; in that is the law of God written; in that is the promise of God revealed. Know thyself; for through thyself only thou canst know God.

Through the glass, darkly. But, except through the glass, in nowise . . . through such purity as you can win for those dark waves, must all the light of the risen Sun of Righteousness be bent down, by faint refraction. [7.261-62]

Denying the Bible and nature as revealed truth, as Ruskin does here, will drastically alter the reading of "broken truth" or symbolic meaning in imaginative art. The sacred truth transmitted in symbolical visions can no longer be reconstructed with any certainty. [238/239]

Ruskin does not deny that the symbolism of human art can convey absolute religious truth; quite the contrary, lie goes out of his way to reaffirm his belief that "the soul of man is still a mirror, wherein may be seen, darkly, the image of the mind of God" (7.260), and that great imaginative vision in particular is divinely inspired (19.309). But from the point of view of the reader, it looks as if he might just as well dispense with mirror and cloud metaphors altogether. The symbolic meaning in art or literature may be divine, but it cannot be interpreted. At the end of "The Dark Mirror" it seems that the cloud-mirror has in fact disappeared: "Therefore it is that all the power of nature depends on subjection to the human soul. Man is the sun of the world; more than the real sun. The fire of his wonderful heart is the only light and heat worth gauge or measure. Where he is, are the tropics; where he is not, the ice-world" (7.262). This looks like a perfect case of mirror turned lamp, Ruskin having finally adopted a wholly romantic and expressionist theory of art—or perhaps, given his wider concern with the nature of perception, arrived by one leap in the twentieth century as a full-fledged phenomenologist. But that is surely not Ruskin's position, and mirror and cloud metaphors (and myths) for a symbolic language that is both human and divine are not gone for good from Ruskin's writing.

If we look somewhat more closely at this passage and the one just before it ("But this poor miserable Me ... by faint refraction"), we can see that the shift from mind-as-dark-glass to mind-as-sun is not a reversal of portion but a shift in point of view. To the beholder of landscapes or the reader of landscape literature and art, man "is the sun of the world; more than the real sun"—

all true landscape, whether simple or exalted, depends primarily for its interest on connection with humanity, or with spiritual powers. Banish your heroes and nymphs from the classical landscape—its laurel shades will move you no more. Show that the dark clefts of the most romantic mountain are uninhabited and untraversed; it will cease to be romantic. (7.255)

This is in fact a restatement of the role of association in perception, as Ruskin had asserted it in Modern Painters III. In the case of landscape art, the human associations that give landscape meaning come not only from figures or buildings in the landscape, but from our sense that the [239/240] composition is itself a reflection of mental process—the sun that illuminates landscape in art is the mind of the beholder, which is in turn guided by the mind of the artist.

But as Ruskin goes on to point out in the next chapters of Modern Painters V, he does not mean to imply that the mind-sun is its own landscape: "[man] cannot, in a right state of thought, take delight in anything else, otherwise than through himself. Through himself, however, as the sun of creation, not as the creation. In himself, as the light of the world. Not as being the world" (7.263). As in Modern Painters III the perception of an object was inseparable from the garland of associated thoughts through which it was seen, so here the mind cannot really grasp and enjoy the world except as the mind itself illuminates it. But there, as here, what we see is not simply the garland or the light of our own sun-minds. Despite Ruskin's romantic interest in the role of associative imagination, he always insists that perception is obtaining information about a world out there.7 To forget this, and adopt a wholly phenomenological model of vision, is to pervert the function of sight. Sight must establish the "due relation" of man "to other creatures, and to inanimate things." When man no longer uses perception to gain information about a world beyond himself, "instead of being the light of the world, he is a sun in space—a fiery ball, spotted with storm" (7.263).

Ruskin, then, adopts the sun metaphor for imaginative perception—quite possibly Turner's own—only with reservations. He retains cloud and mirror metaphors, apparently to express what has ceased to be firm belief (demonstrable by reference to the Bible) and become only undemonstrable hope: that the associations and the symbols in which "information" about the outside world is embedded have also a source outside the individual mind; that the mind reflects or refracts a light it cannot see. For beholders who are interested, as beholders for the most part should be, in information about the world in which they live, the mind is its sun—the beholder's mind and the mind of the artist who shows the world in a different light. But for beholders who want to ask metaphysical questions—and readers of symbolic art will no doubt be faced with such questions whether they like it or not—Ruskin would prefer to keep the cloud or mirror figure for the mind. Without it, after all, it is no longer possible in the world that Ruskin now describes to discover any images of divinity. There is [240/241] no divine authority for the symbolic language of nature, such as the Bible once provided: natural or typical symbolism is all regarded as a product of human imaginative perception. (Natural facts themselves are not imagined, but the symbolical meanings of those facts are.) If the light of the human mind is not a reflection or division or refraction of some higher intelligence, then there can be no language to tell us about divinity.

The sun and the cloud-mirror: Ruskin's terms for alternative ways of viewing the function of art and the artist. The sun-mind illuminates the world by its own imaginative perception; the cloud or mirror-mind transmits the light of sacred truth. Ruskin seems deliberately to pose alternatives, and here one must, I think, see the choice as first of all a compelling personal one. Is he to concentrate on seeing the world (in the increasingly frightening vision of a Turner) or on discovering the transmitted light, the image of divinity? The terms in which Ruskin conceived art before 1859 did not force this choice. To look at the world in nature or in art was then to see images of divinity, imagery easily read against the parallel text of the Bible. In Modern Painters V the two aims are incompatible. Ruskin chooses "to stoop to the horror, and let the sky, for the present, take care of its own clouds" (7.27I).8

In this context we can better understand Ruskin's renewed depiction of Turner as an angel in the sun—this time not as a prophet of merciful revelation, but as the outsize figure with the raised sword (an angel of death, according to the accompanying verses9) standing in the blinding glare of a sun that has all but usurped the canvas. Apart from angel and sun, Turner's painting contains only a few foreground figures fleeing through no clearly recognizable space. How does Ruskin take this angel as his emblem of Turner? First of all, we can note that the allusion to The Angel Standing in the Sun comes at the end of a chapter contrasting Turner with Giorgione. In that contrast the two painters' manners of showing natural light in outdoor scenes is an important element and acquires, not unexpectedly, a figurative meaning. The Venetians, as Ruskin often pointed out, did not actually paint the sun in the sky; to introduce the sun into painting was Claude's great achievement. Giorgione sees Venice under "the limitless light of arched heaven and circling sea" (7.375), with no single source of light specified. The illumination may be read as natural, human, or [241/242] divine; Ruskin implies that for Giorgione, living in an age of faith, there is no distinction among the three. The light of the mind and the light of nature are the divine light. No sense of loss or mystery requires the artist to paint an intervening medium or to locate the source of light. Turner, Ruskin notes, at first follows Claude and the Dutch painter Cuyp, placing the sun visibly in the sky along with the clouds, but painting the sunlight as a golden glow diffused through air or cloud and mist (7.410-11). The young Turner sees a hazy London through fog or dusty sunbeams, loving the diffused light as much as the sun itself, but apparently accepting the visible light as an altered and diminished version of the original sunlight (7.376).

Turner later changes his treatment of sun and cloud, and here Ruskin's Modern Painters V version differs from his early version of the significance of this change. The later Turner abandons the golden glow of sun through cloud for a sun that fires surrounding clouds—and eventually land and sea and even shadows—pure scarlet (7.411-13). In Modern Painters I Ruskin interprets this sun as the light of divine revelation, with Turner himself as the revealing angel. Clouds serve to glorify this light, and sun, clouds, and rainbow color are all given into Turner's hands to celebrate the beauty of God's world. The clouds are neither divine veils nor human mirrors or mists; they simply enhance, without obstructing, the glory of the sun. In Modern Painters V Ruskin reads the victory of light and colored cloud over obscuring mist not as a return to an older faith, but as a statement of the power of the artist's vision: artist and sun are closely identified in Apollo and Ulysses. The triumph of the sun, Ruskin believes, is Turner's statement about the triumph of the artist as hero, not the artist as the servant of God.

There is a change not only in what Ruskin identifies as the source of illumination in Turner's late paintings, but also in what he sees that light as illuminating. In Modern Painters I, when Ruskin stands on the mountain top with Turner, he sees a magnificent natural world with no human inhabitants (3.415-19). In Modern Painters V, when he looks at what the Apollo-artist's vision illuminates, lie discovers that it shows us as much about the nature of darkness—death, disease, and moral evil—as about the triumphant power of light. The bright Apollo reveals the small serpent reborn. Ulysses shows us the interaction of water and underground fire which produces volcanic action: the Polyphemus-volcano is about to erupt as the giant hurls a rock at [242/243] the departing Ulysses. We know from Homer that later the sea god Poseidon, invoked by the volcanic Polyphemus, will produce the storm that wrecks Ulysses. The Apollo-artist's victory still gives new life to the Python; the hero Ulysses' victory rouses the storm that will destroy his companions.

Turner's two late paintings, Light and Colour: Goethe's Theory. The Morning after the Deluge. Moses Writing the Book of Genesis (1843) and The Angel Standing in the Sun (1846), use an iconography similar to that of Apollo and Ulysses.10 Both depict overwhelming suns associated with figures that probably stand for the artist; both also illuminate a world in which an expected purge of evil has not, after all, occurred. Moses records the events illuminated by the blinding sun in which he sits. Those events are represented through the bubble faces rising from the receding flood waters—bubbles that may reflect both the drowned population of the old world (gas released from their decomposing bodies by the sun) and the future population of the purified world. The new life is not only identical with the old; Turner's bubble symbolism, made explicit in the accompanying lines of his poetry, assures us that anything hopeful about the new life will be as ephemeral as the old.11 Death, decay, and moral corruption are still part of the postdiluvian universe. In The Angel Standing in the Sun the angel seems to be simultaneously the angel of the fiery sword driving Adam and Eve (who look in horror on Cain and Abel, revealed to them by sun and angel) out of Eden, and the angel who calls the vultures to "the feast of God" to dine on his enemies, presumably the fleeing wrongdoers in the foreground. In Milton and the Bible, there is another side to the judgment of God in both Genesis and Revelation: the promise of a future salvation. That promise is not revealed by Turner's angel, whose blinding light shows us only a long series of murders.

The defeat of hope on which we are made to look in all of these paintings becomes progressively more terrible as the triumph of light and color—the triumph of the artist—becomes more overwhelming. In the last two pictures we can hardly look at the sun. We are almost forced, like the people fleeing the angel in the last painting, to look away. Here in fact the sun for the first time has not created and filled space but abolished it: the sun is pure color, paint without depth or mystery, pushing to the front plane of the canvas until it nearly crowds the fleeing figures out of the picture. They are still there—but [243/244] they are all that is left of the world of natural beauty, the receding spaces filled with various form and color that Ruskin celebrated in Turner's greatest paintings as the creation of the sun-artist working through the atmosphere. As Ruskin saw it, Turner's sun, the sun of the artist's mind, was finally turned implacably on the facts of life in this world. Ruskin had argued at length in the preceding chapters that such moral realism had been a characteristic of art in all the greatest periods, including classical Greece and the late middle ages and early Renaissance. In most of his work Turner had been the painter of a dynamic natural beauty and power surrounding, at times engulfing, human labor, sorrow, and death. But in The Angel the world of natural beauty has disappeared. Turner's vision, Ruskin suggests, is a modern version of the fully humane but pessimistic vision of Homer or Tintoretto or Dürer, a vision of a universe of death:

the English death—the European death of the nineteenth century—was of another range and power; more terrible a thousand-fold in its merely physical grasp and grief; more terrible, incalculably, in its mystery and shame . . . [Turner] was eighteen years old when Napoleon came down on Arcola. Look on the map of Europe and count the blood-stains on it, between Arcola and Waterloo.

Not alone tliose blood-stains on the Alpine snow, and the blue of the Lombard plain. The English death was before his eyes also . . . life trampled out in the slime of the street, crushed to dust amidst the roaring of the wheel, tossed countlessly away into howling winter wind along five hundred leagues of rock-fanged shore. Or, worst of all, rotted down to forgotten graves through years of ignorant patience, and vain seeking for help from man, for hope in God—infirm, imperfect yearning, as of motherless infants starving at the dawn; oppressed royalties of captive thought, vague ague-fits of bleak, amazed despair.

A goodly landscape this, for the lad to paint, and under a goodly light. Wide enough the light was, and clear; no more Salvator's lurid chasm on jagged horizon, nor Durer's spotted rest of sunny gleam on hedgerow and field; but light over all the world. Full shone now its awful globe, one pallid charnel-house, — a ball strewn bright with human ashes, glaring in poised sway beneath the sun, all blinding-white with death from pole to pole,—death, not of myriads of poor bodies only, but of will, and mercy, and conscience; death, not once inflicted on the flesh, but daily fastening on the spirit; death, not silent or patient, waiting his appointed hour, but voiceful, [244/245] venomous; death with the taunting word, and burning grasp, and in; fixed sting. [7.387-88]

Although Ruskin makes no mention of Turner's painting by name in this description, both are apocalyptic visions of a world of death, lit by a blinding light and presided over by a figure of death. In the following paragraph Ruskin goes on, in fact, to address the reaping angel of Revelation.

Ruskin, I have suggested, would have had a number of reasons for alluding to this painting in constructing his own emblem of Turner's vision. It most fully exemplifies his new view of Turner as a painter of the sorrow of human life and death. It was, moreover, part of a dialogue with Turner begun with Ruskin's description of him in Modern Painters I, to which Turner's painting must have seemed, by the late fifties, a deservedly severe reply. Casting the artist as this different angel, Ruskin could accept—too late for Turner to know—the correction and acknowledge his former misreading of Turner's mind and art; "let not the real nature of it be misunderstood any more." At the same time, this picture of a cloudless, all-powerful sun, turned full on human misery and death, is a fitting emblem for the choice that Ruskin, too, makes in Modern Painters V to abandon the attempt to read a hopeful divine message in the cloudy language of natural types or the Bible and to use, instead, the sun of the human mind "to stoop to the horror, and let the sky, for the present, take care of its own clouds."

There were also reasons why Ruskin might prefer not to invoke Turner's painting by name. Although it could serve very well as an emblem of Turner's last vision, the painting was not, Ruskin believed, a good one12—in part probably because Turner abandons the representation of naturalistic space. Furthermore, Ruskin is here not interested in giving a critical account—descriptive or interpretive—of Turner's painting, but rather in using Turner's imagery as part of his own vocabulary, to say something about Turner—and, directly or indirectly, about himself. To refer to the painting by name would only lead his readers to judge the passage by the accuracy of its description or interpretation, not the issue here.

In technique these paragraphs recall the passage in Modern Painters I where Ruskin describes what the Turnerian artist sees from a mountain [245/246] top. As his notes there indicate, that vision is woven together from a composite of Turner's own paintings and, probably, Ruskin's kindred visions. Here too Ruskin uses his own imagery joined to imagery from more than one Turner (the blood-stained Alpine snow surely comes from Turner's Hannibal, with its allusions to Napoleon;

the winter wind and rock-fanged coast recall any number of Turner's early sea paintings).13 Yet both the imagery and the effects are different. In Modern Painters I the paintings of the artist and the descriptions of the critic are virtually indistinguishable, with the result that the critic seems almost to be competing with his artist as a man of high imaginative vision. Ruskin's understanding of Turner changed as he moved from describing paintings to interpreting them; his understanding of what he himself was doing changed no less radically. His sense of himself as critic—critic of art, of perception, of culture, of society—in The Stones of Venice and the intervening volumes of Modern Painters at first serves to create a critical distance between Turner and Ruskin which was not present in the first volume. There are no more passages, like that at the end of "The Truth of Clouds," in which the painter and his critic see with the same eyes and speak with the same voice.

With Ruskin's description of "the English death" at the end of Modern Painters V, artist and critic come together again. The grounds of their shared vision have greatly altered. In the first place, the power Ruskin assimilates from Turner in this passage is a critical power, not of revealing and rejoicing in what is eternally right and beautiful and true in the natural world, but of pointing out what is wrong in the contemporary human world, an historical world. This is, of course, an identity that Ruskin has already made his own before this second meeting with Turner. Turner's critical method becomes Ruskin's: to use familiar symbolic imagery in a contemporary context, producing a sense of distance and irony as well as of familiarity.

There is a second conjunction between critic and critical artist in this passage. In Modern Painters I Ruskin's prose translates a primarily visual experience. His words add energy, cinematic sweep, a temporal dimension, and occasionally a supratemporal reference to recognizably Turnerian landscapes. The Turnerian paragraphs of Modern Painters V combine images to produce a complex symbol that no one will confuse with a real landscape. Furthermore, the imagery is as much verbal as [246/247] visual. The blood-stained snow, bodies crushed to dust, or rockfanged coast can be visualized, and have been by Turner, but "infirm, imperfect yearning," "oppressed royalties of captive thought," and "vague ague-fits of bleak, amazed despair" are Ruskin's and they cannot be visualized. Ruskin's prose here is no longer descriptive. He is, in a sense, creating a text to go with Turner's images, a text that incorporates and extends and interprets them. The two kinds of imagery are deliberately brought together in a single symbolic statement. For this new use of his visual sensibility and verbal virtuosity, Turner's own practice could of course have served as model. Ruskin had recently reencountered Turner when he set out to read as well as look at his art. That reencounter—which must have taken place over a period of time, probably between 1856, when he began work on the Turner bequest, and the winter of 1859-60, when he wrote the last sections of Modern Painters V—had as profound an effect on Ruskin's writing as the first encounter, reflected in Modern Painters I.

Artist and critic are not, however, so closely identified in Modern Painters V as they were in I. After Ruskin describes Turner's vision of the "pallid charnel house," he explicitly separates his own vision of a modern universe of death from Turner's. Turner identifies his figure in the sun as an angel of the last judgment. Ruskin, after quoting a line from the prophet Joel (3.13) which might appropriately be addressed to that angel, "Put ye in the sickle, for the harvest is ripe," continues:

The word is spoken in our ears continually to other reapers than the angels,—to the busy skeletons that never tire for stooping. When the measure of iniquity is full, and it seems that another day might bring repentance and redemption,—"Put ye in the sickle." When the young life has been "wasted all away, and the eyes arc just opening upon the tracks of ruin, and faint resolution rising in the heart for nobler things,—"Put ye in the sickle." When the roughest blows of fortune have been borne long and bravely, and the hand is just stretched to grasp its goal,—"Put ye in the sickle." And when there are but a few in the midst of a nation, to save it, or to teach, or to cherish; and all its life is bound up in those few golden ears,—"Put ye in the sickle, pale reapers, and pour hemlock for your feast of harvest home." (7.388)

In Turner's version, the figure bringing death to the murderers is both the angel of the last judgment and, probably, the artist; in both cases [247/248] the death he brings is deserved. But Ruskin substitutes an unjust, untimely death. This, he insists, is what the modern English death really looks like. Turner's vision is bleak enough, and critical enough of his contemporaries, but Ruskin's is bleaker and more critical yet.

It should not be surprising that Ruskin finished Modem Painters V in a state of deep depression. In the Turner paintings he read in these last chapters—from Apollo to The Angel— Ruskin was tracing a series of what he saw as self-conceptions by Turner. The series begins with the almost triumphant artist and goes on to show a gradual transformation of artist into critic. There is a shift of focus from the depictions of the triumphant artist and the darkness he (almost) vanquishes (Apollo and Ulysses) to, finally, The Angel in which the artist-critic is himself dwarfed by the unbearable sun of his own powers. The ties between Ruskin and Turner in this last section of Modern Painters are extremely close. Ruskin uses the occasion of his reinterpretation of Turner as a pessimist and a social critic to announce, though somewhat indirectly, his own decision to turn from art to social criticism. He surely saw that the pictures he chose might also serve as emblems for changes in the views of the author of Modern Painters.

To see this, however, would have been to tread on very dangerous ground, for Ruskin also believed that by 1846, when Turner painted The Angel, he had lost full control of his art and his mind—had ceased to produce great art, under the unbearable pressure of that vision of the world as "one pallid charnel house—a ball strewn bright with human ashes."14 Ruskin seems to have imagined Turner burned up, as it were, by the power of his own critical vision. One remembers that Ruskin, earlier in this last section, warns against the solipsistic vision in which the sun usurps the world:

Let him stand in his due relation to other creatures, and to inanimate things —know them all and love them, as made for him, and he for them;—and he becomes himself the greatest and holiest of them. But let him cast off this relation, despise and forget the less creation round him, and instead of being the light of the world, he is a sun in space—a fiery ball spotted with storm.

All the diseases of mind leading to fatalest ruin consist primarily in this isolation. [7.263]

This diseased, usurping sun is very nearly, once again, the sun of Turner's painting. Ruskin did indeed mistrust the apocalyptic critical vision [248/249] he saw here, but already by 1860 he comes very close to sharing it. Turning away from Turner and art criticism in the following decade was, I suspect, more than simply following Turner's example by leaving cloudy romantic art for the horror of the real world. Ruskin was also turning away—though only temporarily, as it turned out—from the apocalyptic mode exemplified for him by The Angel Standing in the Sun, where social and moral realism is finally warped by the very horror of what it contemplates.

uskin is already pulling back from Turner's apocalyptic criticism in these last chapters. Despite passages like that at the end of "The Two Boyhoods" where Turner's vision and Ruskin's are close, Ruskin for the most part writes as a reader or interpreter of Turner's paintings and not as a social critic. I want now to examine his interpretive methods more closely, comparing them both with those he had employed reading nature and the Bible a few years before and with other kinds of reading, Victorian and twentieth-century, to which they may be related. 1 shall focus on what seems to be the single greatest change in Ruskin's methods of reading, his use of a collection of historical texts rather than a single authoritative text to interpret the symbolism of visual art. We shall not have much to do, for once, with clouds and sun, but I may as well point out that Ruskin did in fact integrate his new critical method into the old cloud metaphor for imaginative and symbolic creation. Putting aside the ambiguous triumph of human imagination that he associated with the sun-mind of Turner, together with the unsolvable question of whether or not that vision could also be thought of as a mirror-mind transmitting divine light, Ruskin explored instead what he could describe as another function of the cloud or mirror-mind, the reflections between "minds of the same mirror-temper, in succeeding ages" (19.310). The concept of an historical imaginative tradition, developed in Modern Painters V and The Queen of the Air, is consonant with Ruskin's ideas about the uses of history for criticism developed in The Stones of Venice. This special form of historical criticism is Ruskin's alternative to Turner's last apocalyptic vision and, at the same time, the context and justification for Ruskin's own occasional ventures into that mode.

To begin, however, with specifics: How does Ruskin approach [249/250] Turner's symbolic paintings? In Modern Painters V he looks less at visual richness than at selected signs, visual and verbal. He considers these signs not so much as statements of meaning in themselves but as clues or guides to the way landscape and formal elements are to be experienced. The interpretive procedure is worked out in his 1857 catalogue of oil paintings from the Turner bequest. There for the first time he was concerned with reading Turner's work:

There is something very strange and sorrowful in the way Turner used to hint only at these under meanings of his; leaving us to find them out, helplessly; and if we did find them out, no word more ever came from him. Down to the grave lie went, silent. "You cannot read me; you do not care for me; let it all pass; go your ways." [13.109]

Turner had, nonetheless, left three kinds of hints, words, or, as Ruskin elsewhere refers to them, clues to his "under meanings": his titles, the texts he appended to the listings of his pictures in the Royal Academy exhibition catalogues, and the figures he put in his landscapes. Ruskin's readings of Turner's paintings, in both the 1857 catalogue and the last volume of Modern Painters, almost always begin from the title and frequently make a special point of directing attention to texts and figures. Thus Ruskin notes, "The course of [Turner's] mind may be traced through the . . . poetical readings very clearly" (13.125), and the choice of subject in his manuscript poem "The Fallacies of Hope" is "a clue to all his compositions" (13.159). He often treats Turner's figures as equally textual, pointing out that they are rendered with Hogarthian realism in his early work and become increasingly schematic in later works (13.109, 151-57).15 Regardless of period, Ruskin finds, "in almost every one of Turner's subjects there is some affecting or instructive relation to [the landscape] in the figures . . . the incident he introduces is rarely shallow in thought" (13.152).

Ruskin's reading of The Bay of Baiae is representative (l3.l3l-35). He begins with the appended text, "Waft me to sunny Baiae's shore, noting the "spirit of exultation" as typical of Turner's delight in highly colored Italian landscapes at this period. But going on to describe the painted landscape, he points to an apparently discordant element: it is a landscape of ruins whose appearance is treated with such delight. The decisive clue to Turner's meaning he finds in the figures: [250/251]

"If, however, we examine who these two figures in the foreground are, we shall presently accept this beautiful desolation of landscape with better understanding." Identifying the figures as Apollo and the Sibyl (information, he notes, provided in the full title of the painting), Ruskin uses the mythical story to gloss the puzzling aspect of the scene ("We are rightly led to think of her [the Sibyl] here, as the type of the ruined beauty of Italy")—concluding his reading by pointing to a related painting. The Golden Bon fi, in which the same Sibyl (this time accompanied by a snake) indicates again the "terror, or temptation, which is associated with the lovely landscapes" in Turner's mind. Ruskin characteristically moves back and forth between texts (including figures) and the landscape, with the final emphasis always on the latter. There is no absolute division between a purely representational landscape and a symbolic language of mythological figures or verbal tags. The tags instead act as additional glosses, hints, or signs to an under meaning to be read in the landscape itself. Thus Ruskin frequently points to ways in which Turner has translated the mythical figures or actions into purely naturalistic terms. The glacial form of the dragon in Hesperides expresses the physical and moral significance of the dragon suggested in Hesiod's genealogy.

Two aspects of Ruskin's procedure need stressing. First, reading, as illustrated by Ruskin's interpretation, is different from but not a substitute for the active seeing exemplified by his descriptions. Titles, texts, or painted hieroglyphs always point back to landscape. They serve as a guide to one of the most difficult problems of reading a visual work. that of deciding what visual marks are significant. Ruskin seems to assume that both the first and last experience of a landscape painting should be the kind of looking he had urged in earlier works.16 By beginning and ending with expectations of careful seeing, he implies that, though not all visual elements are symbolic, no detail fails to contribute to a reading of the painting. In the second place, Ruskin is quite careful to begin his interpretations from the specific signs provided by Turner. He has a firm sense of where those additional, textual clues are to be found, suggesting a sequence of interpretation specific to Turner's work. (He makes no claim that titles, texts, and figures will be the guides to meaning in all painting.)

The interpretive procedure worked out for Turner is in many ways closely parallel to the reading of sacred texts with which Ruskin was [251/252] concerned in the preceding section of Modern Painters. There Ruskin took the written text of the Bible as his guide to reading the created B world. Scripture suggested what aspects of the visible world could be significant and provided an authoritative guide to the under meaning of those significant aspects as well. With Turner's painting, as with divine symbolic language, Ruskin's interpretive procedure is to juxtapose two different kinds of meaningful creations, one visual, the other verbal or hieroglyphic (in either case a more explicit sign) and to use the latter as guide to reading the former. The process is actually more complex, of course—the interpretation of the words or signs itself involves comparison of different passages (from the Bible, or from Turner's other poems or paintings, or from his reading); further, the written or hieroglyphic texts are themselves illuminated by the painted or created landscapes. The two kinds of creations, textual and visual, are in each case related (they are by the same author and have been put together by the same author) but not identical. The visual creation in particular cannot be reduced to textual signs. There is always a surplus of information. It is these visual nuances and details, which cannot be specified by hieroglyphs or words, which may in turn enrich understanding of the texts. The exegesis of written and created word together seems to provide a pattern for Ruskin's reading of Turner's paintings. Visual and verbal elements are considered to work together like the two mutually illuminating creations; they are deliberately set in relationship to one another by their author. In Ruskin's verbal-visual reading, as in his purely visual explorations, overall structure is not a primary concern.

There are, however, some significant differences between Ruskin's readings before 1856 and his readings in Modern Painters V and afterwards. The most obvious change is that there is no single authoritative text to place beside Turner's paintings. Not only does Turner himself use a variety of textual materials, but these in turn need explication from yet other texts, not all by Turner, not all specifically alluded to by Turner, not all even definitely known to have been read or used by Turner. In this almost infinitely expansive process of interpretation a there is no ultimate written text comparable to the Evangelical's Bible. Ruskin had of course been using multiple texts to read the symbolism of human art ever since The Stones of Venice. For the capitals on the Ducal Palace he turns not only to their inscriptions but also to Spenser, [252/253] Dante, Bunyan, and Giotto. But in these earlier readings there is always a final text, and that text is always from the Bible. Ruskin's procedure in Modern Painters III is typical of his approach before 1859: he examines the significance of fields or grass in medieval art and literature by moving back and forth between Dante and various manuscript illuminations, contrasting these with Homer, but he concludes his reading by appealing first to his readers' perception of actual grass, as the authority for all visual representations or descriptions, and second, to the meaning of grass as established in a collection of passages from the Bible (5.284, 293). When Ruskin reads Turner's Hesperides, he uses, besides Turner's title and the figures of dragon and goddesses in the painting, the following additional texts (I give them In the order cited): Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography Diodorus Siculus, Hesiod, Matthew, Euripides, Apollodorus, Genesis, Psalm 74, Exodus, Dante, Lucian, Milton, Job, Coleridge, Homer, Virgil, and Spenser. Job, Matthew, and Genesis have as much illuminating value as any other of the texts Ruskin cites, but no more. Experience is still the final authority for truth of representation, but Ruskin does not refer symbolic meaning to the Bible as a privileged text. For that single, divine text he substitutes a cumulative historical tradition in which the Bible itself is included. The procedure is put forward as a principle of interpretation ten years later in Ruskin's lecture on myth, The Queen of the Air, using, as I have already indicated, a mirror metaphor: "its [a myth's] fulness is developed and manifested more and more by the reverberation of it from minds of the same mirror-temper, in succeeding ages. You will understand Homer better by seeing his reflection in Dante, as you may trace new forms and softer colours in a hillside, redoubled by a lake" (19.310).

Ruskin's new reliance on secular tradition as the underlying text against which to read symbolic meaning in art is, of course, immediately related to a major change in his religious views. Between 1856 and the winter of 1859-60 he had given up his old belief in the Bible as the direct word of God, a divine symbolic language.17 The problem with which he had been wrestling—of two kinds of symbolic language and the degree to which these might coincide in great art—did not disappear; we have noted that he continued to inquire whether imaginative inspiration might not be at times equivalent to divine inspiration. But practically speaking, Ruskin was no longer faced with [253/254] two different methods of reading symbolism, the one historical and psychological (against artistic and literary tradition), the other ahistor ical (against a divine text).

Ruskin's use of historical tradition to establish meaning for the symbolic imagery of a particular painting or text is nonetheless rather different from the historical approach to iconography taken in this century by Irwin Panofsky and others Ruskin's tradition is not constructed on the principle of historical development and influence, whether from individual to individual or within the shared context of a common culture. What counts for him is not the illumination of a particular picture or phrase, but our understanding of the image or figure itself, whose meaning is greater than and independent of any particular picture or text in which it occurs. Thus the critic constructs a tradition in order to multiply and enlarge the potential meaning of image or metaphor or myth, not simply in order to specify its meaning in a given text by selecting only those uses of the figure that author or artist could have known. The procedure is by no means completely unselective; context in the work in question puts limits on what examples of the image or figure will be relevant. Ruskin gives some attention to historical and cultural probability, but he is much less rigorous than a modern historical scholar with different intentions. Furthermore, Ruskin is able to cite many more examples than are directly appropriate historically, culturally, or contextually, because he cites them to differentiate nuances of meaning rather than to point to identities. Again, the value of a tradition, in Ruskin's approach, is not to prove a line of historical development or influence, but to enrich the potential meaning of image or figure by discovering connections between its meaning in different works without reducing or conflating the individual variations.

Ruskin's tradition is probably closer to that of nineteenth-century poets like Blake, Baudelaire, and particularly Swinburne.18 Swinburne envisions the relation of one poet to another within an historical tradition in an image very close to Ruskin's:

And one light risen since theirs [the Jacobean tragedians] to run such race

Thou hast seen, O Phosphor [Marlowe], from thy pride of place,

[254/255]

Thou hast seen Shelley, him that was to thee

As light to fire or dawn to lightning; me,

Me likewise, O our Brother, shall thou see,

And I behold thee, face to glorious face? ["In the Bay," stanza 26]

The image of varied forms of the same light to describe the brotherhood of imaginative poets is no doubt Shelley's ("thy light, / Imagination! which . . . / As from a thousand prisms and mirrors, fills / The Universe with glorious beams" — "Epipsychidion," 11.163-164, 166-167), but it acquires in Swinburne's hands, as in Ruskin's, an historical meaning, describing relationships across time. As used by both Ruskin and Swinburne, the image suggests that the later poet's reflection of a song or image is not viewed as part of a causal sequence of development (from which an original poet might feel obligated to escape) but as a variation on a common light, a variation that adds to something all the poets have in common.21 The emphasis falls on the multiplication and variation of light, not on the degree of resemblance or difference or of progressive development between successive versions of a similar image. For Swinburne or Ruskin, songs or images are still alive, ready for use and reuse, but constantly changing each time they are reused.22 Swinburne explicitly describes the historical series of great singers as a living tradition; he delights to proclaim the kinship of such singers, regardless of their historical knowledge of one another:

But the life that lives for ever in the work of all great poets has in it the sap, the blood, the seed, derived from the living and everlasting word of their fathers who were before them. From Aeschylus to Shakespeare and from Shakespeare to Hugo the transmission of inheritance, direct or indirect, conscious or unconscious, is as certain and as traceable as if Shakespeare could have read Aeschylus and Hugo could have read Shakespeare in the original Greek or the original English.23

In that living tradition individual poets do not speak the same language. They are culturally and historically distinct. Yet each nonetheless is fully present, in his individual historical particularity, for his successors who will repeat, but not exactly, what he has said. For Swinburne as for Ruskin this relationship holds not only between a poet and his predecessors but also between a critic and the poetical tradition [255/256] he traces. The move from interpretation to reuse is a natural one for both poet and critic.

These attitudes toward artistic tradition might be compared to the philological approach to meaning represented by the modern historical dictionary, whose origin, in England at least, dates to just this period, the second half of the nineteenth century. Historical quotations, chronologically ordered, are used to build up a range of meanings for a word. The value of historical quotations is to create a "text" that is read together with the single instance in a reciprocal process of interpretation. We read a contemporary instance of "cloud" in light of the varying historical uses of "cloud" in the dictionary's collection of quotations, just as Ruskin reads Turner's Hesperidean dragon in light of the dragons in Hesiod, Dante, Revelation, and so forth. At the same time, we reread the whole conception of cloud or dragon in light of the present writer's or Turner's version of it. The goal is not simply an historical record of the word "cloud" or the image "dragon" but, more importantly for most readers, an expanded sense of the word or symbol approached as an element in a living language, a word we might want to use ourselves. The modern historical dictionary fosters an historical consciousness in the current user, while making available accumulated nuances of meaning; the record of different meanings need not be used merely to trace a line of development or to interpret the meaning of some past instance of the word. Ruskin's The Stones of Venice, intended for the use of contemporary patrons of architecture, presents the history of Byzantine, Gothic, and Renaissance styles with the same double aim: to reinforce historical consciousness of both past and present moments, while making some parts of that past available as a living tradition for reuse in the present.

The analogy with the historical dictionary has a more direct relevance to Ruskin's interpretations of symbolic painting in Modern Painters V. The Oxford English Dictionary, the great example of the historical dictionary, was conceived in the late l850s; through its founders Ruskin was first exposed to the new philological methods. His fascination with historical philology is widely evident for the first time in the last volume of Modern Painters. When, for example, Ruskin interprets "heavens" in Psalm 19 (a passage probably composed in 1856 but revised in 1859), he begins by tracing the various meanings of the Hebrew, [256/257] Roman, and Greek words for "heavens" and their relation to the English term (7.195-196). That Ruskin became interested in contemporary philology at the same time that he began to gloss the symbolism of Turner's paintings from an historical collection of texts is not accidental.

There is external as well as internal evidence that Ruskin turned to the philological methods of F. J. Furnivall, F. D. Maurice, and particularly R. C. Trench sometime in the late l850s. Ruskin knew their work earlier; in 1851, and again as late as 1854, he had disagreed strongly with their historical approach to language, especially biblical language. The three men rejected much of the literal content of the Bible, using historical arguments about its language to support interpretation of many passages as poetic, mythic, or figural expressions that were not to be taken as literally true. Before 1858 or 1859, this approach was not acceptable to Ruskin. In 1854, he records in Praeterita, he was shocked to hear Maurice during a Bible lesson tell his listeners that they should ignore the literal example of Jael as morally anachronistic; in reply to a question from Ruskin about how one should then take the praise of Jael (who pierces the head of Sisera with a nail) by the prophet Deborah, Maurice replied, again to Ruskin's "sorrow and astonishment," that Deborah's speech was (in Ruskin's words) "a merely rhythmic storm of battle-rage, no more to be listened to with edification or faith than the Norman's sword-song at the battle of Hastings" (35.486-87). The issue between Maurice and Ruskin had been joined three years before, in a three-way correspondence mediated by Ruskin's friend Furnivall, over Ruskin's literal reading of St. Paul in his pamphlet On the (construction of Sheepfolds (1851). In reply to objections from Maurice and Furnivall, Ruskin admitted that he did not consider the "etymological force" of the terms in question, but vigorously defended ignoring evidence of historical changes in meaning on the grounds that the Bible was intended to speak directly to simple people at all times—in other words, that it should be taken as the literal word of God and not as a human text written in an historically changing language. The differences between himself and Maurice and Furnivall, he wrote to the latter, came down to "the endless question of Authority of Scripture, into which it is vain to enter. I say only this—If the Bible does not speak plain English enough to define the articles of saving faith, burn it, and write another, put don't talk of Interpreting it" (12.570). [257/258] Two years later, in 1853, Furnivall sent Ruskin a copy of R. C. Trench's Study of Words (1851), to which Ruskin replied: "I am afraid it will not convert me" (36.146). But some time between 1856 and 1864 Ruskin seems to have changed his mind, writing again to Furnivall:

as it happens, I am just now profiting not a little by help you gave me long ago; you know how you used to find fault with me for speaking ill of philology, and how you, in alliance with the Dean of Westminster [Trench], first showed me the true vital interest of language. While I have not one whit slacked in my old hatred of all science which dwelt or dwells in words instead of things, I have been led by you to investigations of words as interpreters of things, which have been very fruitful to me; and so amusing, that now a word-hunt is to me as exciting as, I suppose, a fox-hunt could be to anybody else. [38.332]

Furnivall and Trench were together chiefly responsible for the Philological Society's ambitious project, begun between 1857 and 1859, for a new English dictionary combining full etymologies with extensive historical and literary illustrations of changing usage. No longer, after 1858, resisting the historical approach to language, Ruskin not only learned from them the gleeful pleasures of the word hunt, but also, I think, took over from them the practice of collecting historical examples of a word in context—took over and applied to the task of interpreting the meaning of symbolical images and of myths.

The dictionary example seems to me not only relevant, given Ruskin's connections with philology through Furnivall and Trench, but also helpful in explaining the peculiar kind of tradition or history of an image that Ruskin assembled. As with the dictionary, so in Ruskin's collections of texts for interpreting a given image, the collection itself may be historical (historically significant instances of usage where clear variations in meaning can be differentiated), but the use to which one puts the historical information need not be. What a word means depends finally on how it is used in a particular context, and that use may draw on any or all of the past and hence potential meanings of the word. Its reuse will then become part of its meaning, as presented by the dictionary to the reader and writer. The difference between iconological criticism like Panofsky's and Ruskin's, then, is partly the difference between compiling a dictionary of a dead language, which cannot [258/259] be addressed to a potential user, and compiling an historical dictionary of a still living language. Traditional iconography has perhaps become more or less a dead language in an age of nonrepresentational art, but both traditional visual symbolism and myth were very much alive, or at least capable of being resuscitated, for Ruskin.24

The emphasis on recovering possibilities of meaning, rather than constructing a history, is characteristic of Trench's Study of Words and is much more explicit there than in the OED itself. Language for Trench, too, is very much alive. Words are "not merely arbitrary signs, but living powers."25 They have a life of their own which fascinates Trench much as the life of the nonhuman natural world does Ruskin. Trench justifies the historical study of language on three grounds: language preserves a record, first, of various historical changes—social, political, intellectual; second, of imaginative insights; and third, of moral insights. In only the first sense is the meaning of a word historically limited and particular, of no immediate interest to a current user. Insofar as words at different periods reflect imaginative or moral insights, however, these meanings are never really outdated; if they are not now current, this does not prevent them from functioning as part of the potential meaning of the word. Indeed, Trench implies an obligation to revive such lost meanings: "Where use and custom have worn away the significance of words, we too may recall and issue them afresh" (p. 133). The "we," in this case, are the students at the Training School for teachers in church-supported schools, and the recalling and reissuing of words—the comparison is with worn coins—is specifically a recommendation as to "how we may usefully bring our etymologies and our other notices of words to bear on the religious teaching which we would impart in our schools." As Trench makes clear, historical philology does not primarily tell him that the same word has meant different things at different times, and hence that meaning is relative, but rather that every word has "one central meaning," variously developed, altered, or forgotten. To get at that meaning is to recover an insight whose validity does not change. Regarded as "fossil poetry," a word may "be found to rest on some deep analogy of things natural and things spiritual"; alternatively, language may be "fossil ethics": in using it "men are continually uttering deeper things than they know, asserting mighty principles, it may be asserting them against themselves, in words that to them may seem nothing more than the current coin of society" (pp. 121-22, 11-I2, 14). [259/260]

Ruskin's conception of significant images, symbols, and myths seems to be formed by analogy with Trench's conception of language. Myths, he asserts in The Queen of the Air, are words in a literally and historically living language of natural things: "words of the forming power" (19.378). Myths have their roots either in "actual historical events, represented by the fancy under figures personifying them," or in "natural phenomena similarly endowed with life by the imaginative power, usually more or less under the influence of terror" (19.299). Ruskin is even less interested than Trench in myths as they reflect historical events or situations; he concentrates on myths that originate in some imaginative perception of natural phenomena. These too have a history. The development of a myth, or of mythical names or images, can be used to trace out or exemplify a history of consciousness, of religious or ethical thinking, of aesthetic or intellectual changes in a culture. But all myths, and especially those originally referring to natural phenomena, are more than historical artifacts ("fossil history"). They preserve, as words do for Trench, "true imaginative vision" that "perceives, however darkly, things which are for all ages true" and "moral significance . . . which is in all the great myths eternally and beneficently true" (19.309, 310, 300),

and it is this veracity of vision that could not be refused, and of moral that could not be foreseen, which in modern historical inquiry has been left wholly out of account: being indeed the thing which no merely historical investigator can understand, or even believe. [19.309]

The task of the philologist, Ruskin tells his readers at the beginning of his lecture on myths, is to account for the errors of antiquity; his own, by contrast, is to read the thoughts of these men (19.296). That reading, like Trench's, ultimately requires the reader to issue afresh the worn words or myths he examines.

I think the reader, by help even of the imperfect indications already given to him [in the preceding two lectures], will be able to follow, with a continually increasing security, the vestiges of the Myth of Athena; and to reanimate its almost evanescent shade, by connecting it with the now recognized facts of existent nature, which it, more or less dimly, reflected and foretold. [19.385; my italics] [260/261]

The limitations of philology or "modern historical inquiry" to which Ruskin refers point not to Trench but to the leading exponent in England of the philological school of comparative mythology. F. Max Muller lectured at Oxford throughout the fifties and gave two series of popular lectures on language in London in the early sixties. Ruskin refers to these in his own lecture on language and books ("Of Kings' Treasuries," 1864) and his lectures on Greek myth (The Queen of the Air). Muller combined word hunts with myth hunts, tracking down the origins of mythical thinking through various Indo-European languages back to Sanscrit. But where Trench and Ruskin tried to recover the meaning of words or myths in order to restore them to language, Muller saw myth as an accident, a mistake: myths arose to explain metaphorical words whose original reference had been forgotten or distorted. Hence myth, far from being a potential living power, was, in Müller's famous phrase, a disease of language.28 By implication, the historical philologian's task was not to restore meaning to myth, but to demythologize language, to reduce its metaphorical terms to rational perceptions. (Müller tended to regard these perceptions as, in any case, primitive and unscientific, of historical interest only.) Ruskin drew heavily on Müller's word hunts because they frequently connected mythical beings with perceptions about nature (most of Müller's deities turn out to be descriptions of the sun or other elements). But Ruskin, like Trench and unlike Müller, looked to met aphoric language and myth for continually valid imaginative and moral perceptions—and indeed for scientifically accurate physical perceptions as well.

On this last point Trench and Ruskin differ. Though Trench collects texts to show significant variations in usage in order finally to recover a fuller meaning for current use, he continues to take the Bible, however liberally read and interpreted, as the authoritative moral and spiritual text against which the insights stored up in words can be evaluated. The truths of the Bible story— that man is of "a divine birth and stock," "fallen, and deeply fallen, from the heights of his original creation," but elevated and redeemed by Christ—he finds reflected and confirmed in the histories of words (Study of Words, pp. 25-29) Furthermore, it is his readers' knowledge of, and belief in, the truths of scripture which will enable them to understand and restore to use the worn or forgotten moral insights preserved in language. Because "we"—his audience of Anglican [261/262] teachers-in-training—believe in the revealed truth of the Bible, "we only rejoice at each new homage which [philological] Science pays to revealed Truth, being sure that at the last she will stand in her service altogether" (p. 45). This is very close to Ruskin's attitude toward the results of his own historical science applied to the symbolic language of stones in The Stones of Venice.

In Modern Painters V or The Queen of the Air, however, what enables us to reanimate myth and symbol, once we have assembled the cumulative tradition in which meaning is expanded and expressed, is not belief in the biblical revelation but accurate, imaginative perception of the concrete phenomena to which myth or symbol originally or literally refer. Müller was interested in this literal reference of words and myths though he regarded the perceptions on which literal meaning was based as outdated or unscientific. Trench was not much interested in the value of original literal reference at all. For Ruskin, we can only understand the true vision, moral and imaginative, developed and elaborated in myth "so far as we have some perception of the same truth" (19.310). In the case of Turner's myths and the Greek myths that Ruskin treats in The Queen of the Air, that perception is a perception of nature:

If it [the myth] first arose among a people who dwelt under stainless skies, and measured their journeys by ascending and declining stars, we certainly cannot read their story, if we have never seen anything above us in the day but smoke; nor anything round us in the night but candles ... we can only understand the story of the human-hearted things, in so far as we ourselves take pleasure in the perfectness of visible form . . . we shall be able to follow them into this last circle of their faith only in the degree in which the better parts of our own beings have been also stirred by the aspects of nature, or strengthened by her laws. It may be easy to prove that the ascent of Apollo in his chariot signifies nothing but the rising of the sun. But what does the sunrise itself signify to us? ... if the sun itself is an influence, to us also, of spiritual good . . . [it] becomes thus in reality, not in imagination, to us also, a spiritual power . . . [and we may] rise with the Greek to the thought of an angel who rejoiced as a strong man to run his course, whose voice, calling to life and to labour, rang round the earth, and whose going forth was to the ends of heaven. [19.302-303]

Ruskin's last lines paraphrase no Greek source but verses five and six of Psalm 19. Like the Greek myth, he implies, the Hebrew symbolism [262/263] cannot be reanimated unless it can be refounded in an attitude toward nature which sounds very much like the modern landscape feeling feeling described in Modern Painters III: clear perception, pleasure in visible form, a nonpathetic emotional responsiveness to the aspects of nature, especially to signs of the alien life in natural things. Ruskin is still in agreement with Trench when he says that collecting evidence of historical changes in language and myth, as Müller does, is not enough." Words must be reissued for present use, their moral and imaginative insights restored. But Trench or Maurice or Furnivall would hardly recognize Ruskin's method of restoring meaning to symbolic language by referring all of it—including the Bible—to the accurate, imaginative visual exploration of nature. Ruskin was in his interpretations refusing to follow the lead of Turner's last symbolic paintings—refusing to abandon naturalistic reference and the landscape feeling as the basis of a symbolic language fitted for current critical use.