English anarchism has never been anything else than a chorus of voices crying in the wilderness, though some of the voices have been remarkable. — Woodcock 414

Introduction

narchism was founded on the doctrine that all forms of government are oppressive and should be abolished. The core of anarchist ideology was critique of authority and social hierarchy. As a global political movement anarchism emerged within the International Workingmens Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864-1876). In a few years a split was made in the organisation between the followers of Karl Marx (reds) and Mikhail Bakunin's anarchists (blacks). The anarchist bloc held a separate congress at St. Imier, Switzerland in 1872 and proclaimed itself to be the true heir of the First International. The strong ideological cleavage between anarchists and Marxists was widened at the Second International (1889-1916).

Precursors of British Anarchism

Gerrard Winstanley, on a mosaic memorial to the Diggers

in Cobham, Surrey, where the movement started.

In late Victorian Britain, anarchism was chiefly perceived as a foreign import, although genuine anarchist ideas began to develop in England in the seventeenth century in the circles of radical Whigs and Protestant nonconformists. The first two major domestic precursors of late Victorian anarchism were Gerrard Winstanley (1609-1676), who published a pamphlet The New Law of Righteousness (1649), calling for common ownership and social and economic organisation in small agrarian communities, and William Godwin (1756-1836), who expressed anarchist views in his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793), arguing that people as rational beings can live in harmony without laws and institutions in a stateless society. Godwin attacked the Church, the government and the legal system as an instrument of oppression. He criticised monarchy as a corrupt form of government. Today Godwin's book is regarded "as one of the founding documents of classical anarchism" (Ryley 3). Godwin's son-in-law, Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), was the third major precursor of British anarchism. He expressed anarchist sentiments in some of his poems, most notably in The Mask of Anarchy (1819), written after the Peterloo Massacre. In Shelley's poem "anarchism first appears as a theme of world literature" (Woodcock 85). The fourth precursor, William Blake (1757-1827), who did not support any type of institution, including the Church, State and the King, and strongly advocated liberation from authority, is considered by some as "a Christian anarchist" (Paananen XIII). Peter H. Marshall called Blake a "visionary anarchist" and (together with Godwin) "a founding father of British anarchism" (1998). However, in his own time, unlike Godwin, Blake did not exert any impact on his contemporaries because his anarchist views were then hardly known.

"The Peterloo Massacre (or Battle of Peterloo)," published by Richard Carlile; aquatint and etching, 1 October 1819. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, NPG D42256.

Late Victorian anarchism was heavily indebted to both the Chartist and socialist ideology, but the man who gave name to the movement was the Frenchman Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865). He was the first to use the term anarchy to describe his ideas about social order in his book Qu'est-ce que la proprit? Recherche sur le principe du droit et du gouvernement (What Is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government, 1840). Proudhon's views were developed by his friend and follower the Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin (1814-1876). They are both regarded as founders of global anarchism, although they represented two opposing sides of this political ideology. Proudhon propagated a nonviolent takeover of power, whereas Bakunin believed that violence is necessary to overthrow the obtrusive authoritarian state. After Bakunin's death in 1876, another exiled Russian, Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921), became one of the chief proponents of anarchism as a political movement, but he rejected Bakunin's violent rhetoric and instead advocated non-violent methods of reforming society.

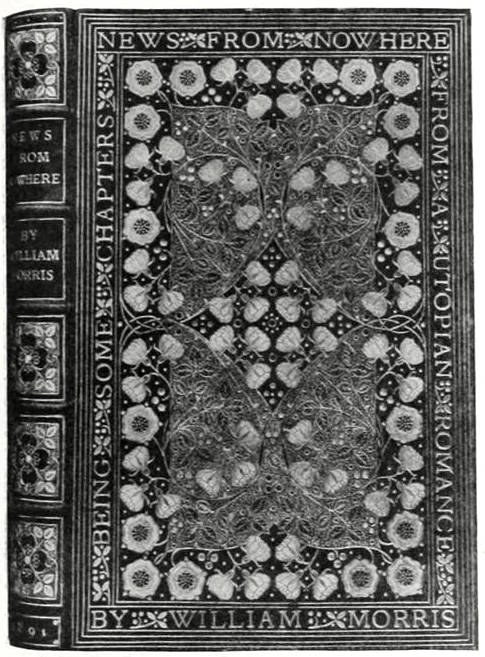

Luxury leather binding of c. 1905 for Morris's

News from Nowhere by George Sutcliffe (1878–1943).

Kropotkin, as an advocate of anarchist communism, exerted a significant influence on British radical thinkers, including William Morris (1834-1896), whose attitude to anarchism and communism was curiously contradictory and ambivalent. In his best-known fiction, News from Nowhere (1890), Morris depicted a future utopian anarchistic (communist) paradise, but soon he withdrew from the anarchist-dominated Socialist League and its newspaper Commonveal, which supported revolutionary violence as a means of achieving anarchist goals. Nevertheless, Kropotkin wrote in his obituary of Morris that in News from Nowhere he "produced perhaps the most thoroughly and deeply anarchist conception of future society that had ever been written" (110).

Influx of foreign anarchists

In late Victorian Britain, anarchism failed to develop as a distinct political movement. It was mainly propagated by a small number of radical intellectuals, mostly men of letters, and foreign activists who found political refuge in London. Britain was the only European country which had a very liberal asylum policy and thanks to it attracted foreign (exiled) radicals, including dedicated anarchists, who spread anarchist ideas among British men of letters, intellectuals, journalists and industrial workers. Foreign and native anarchists lived and acted under a constant scrutiny of the police, but unlike other countries, they were not repressed if they did not commit a crime. Anarchism was the subject of heated parliamentary debates and sensational newspaper articles. As a result of the laws which curtailed socialist and communist activities in Germany, France, Spain and Russia, a sizable influx of anarchists sought political asylum in Britain. Anarchist agitation in late Victorian Britain was chiefly concentrated in immigrant clubs in the poor neighbourhoods of London. The Rose Street Club in Soho, formed by the German migrant workers' education group in 1877, the Autonomie Club on Windmill Street, founded in 1878, and later (after 1885) the International Club on Berner Street in Whitechapel were the most famous meeting places for immigrants with anarchist views. Scotland Yard discreetly monitored the political activity of these individuals, but according to the gentlemen's agreement, most radicals, with the exception of the Irish, refrained from spectacular acts of terror in England. Great Britain was the only European country which allowed political exiles to live, work and publish their opinions freely. British law did not authorise extradition for discussing political ideas or holding unorthodox opinions. It was the passing of the Aliens Act of 1905 that changed radically the British policy toward immigration. A rapid increase in socialist and anarchist activities in late Victorian Britain was believed to be the direct consequence of an increased immigration, particularly of poor Jews fleeing Russia from pogroms. Attempts to pass the laws curtailing immigration were rejected by Parliament in 1894 and 1903, but eventually, the Aliens Act came into force on 1 January 1906 and halted the uncontrolled flux of "undesirable immigrants", mostly impoverished Jews from Eastern Europe.

The emergence of British anarchism

The first British association which manifested some anarchist ideas was the London Confederation of Rational Reformers (founded in 1853) by Ambrose Cuddon (1790-1879), an early associate of Robert Owen and a Chartist. It was composed of seceders from James Bronterre O'Brien's National Reform League (1849-1874), which advocated socialist ideas. Cuddon is regarded by some as the first self-styled English anarchist. According to the anarchist historian, Max Nettlau, Cuddon published the first anarchist pamphlet in England in 1853 (36), and later, in the 1860s, contributed to the first anarchist journal in English, The Cosmopolitan Review (101). Genuine British anarchism emerged principally from the utopian association known as the Fellowship of the New Life, founded in 1882 by the Scottish-American scholar Thomas Davidson (1840-1900), "an ethical anarchist communist" (Beer 274), as an intellectual discussion and study group dedicated to developing models of moral regeneration through the creation of a communistic society. Its most famous offshoot became the socialist Fabian Society founded in 1884. Many British philosophical anarchists were drawn to both organisations and adopted some of their ideas concerning a nonviolent reform of society. "The rise of British anarchism coincided with the appearance of ever-widening cracks in the façade of Victorian optimism and complacency" (Shpayer-Makov 492).

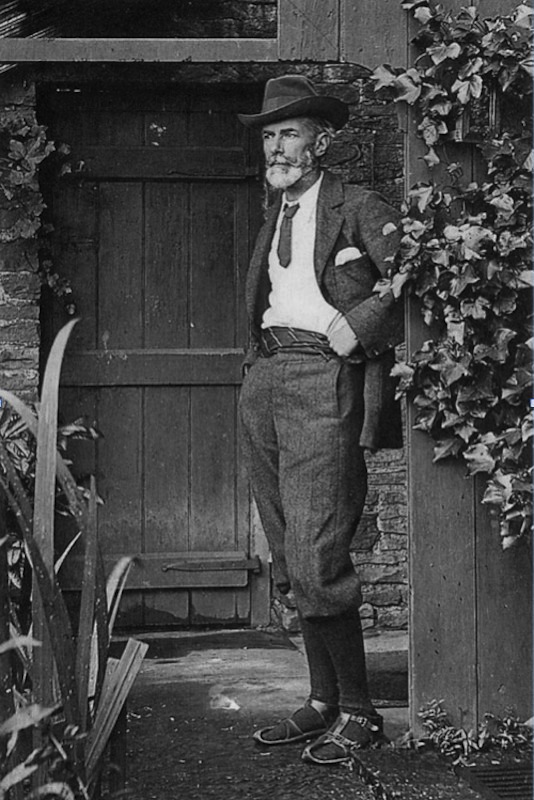

Edward Carpenter, photographed in his sandals by Alf Mattison, 1905; copied by Emery Walker. © National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG x87106.

It is often claimed that the early 1880s marked the true start of British anarchism, however, it should be emphasised that anarchist activity in late Victorian Britain was generally nonviolent and rather small in scope. Despite its marginal size, the British anarchism of the late Victorian period was very diversified. Its proponents included native and immigrant communists, libertarians, middle-class faddists, rural communitarians, Christian pacifists and industrial unionists (Shpayer-Makov 488). Anarcho-communism and, and later, at the turn of the century, anarcho-syndicalism were the two major strands of foreign anarchist thought in Britain. A minor but genuine British school included individualist anarchism, rooted in the political and philosophical views of William Godwin and Edward Carpenter (1844-1929). The latter was sometimes called "the English Tolstoy (Hardy 23) because he tried to blend pacifism, spirituality and anarchism in a Tolstoyan manner. Like the great Russian realist writer, Carpenter was an influential social reformer, pacifist, vegetarian, and a radical prophet of a new age in which social relations would be based on a worldwide spiritual awakening and socialism. "Individualist anarchism offered a distinctive anti-statist perspective"(Ryley 110).

Individualist anarchism

One of the forerunners of individualist anarchism in Britain was Wordsworth Donisthorpe (1847-1914), a political theorist, barrister, and also a pioneer of cinematography, who published controversial books on the limits of individual liberty, such as Individualism: A System of Politics (1889) and Law in a Free State(1895). He also edited Jus: A Weekly Organ of Individualism (1885-1888). Donisthorpe did not clearly identify himself as an anarchist, but his concept of individualism and critique of state exerted influence on the emergence of the strand of individualist anarchism in Britain. One of the more prominent representatives of individualist anarchism was Henry Seymour (1860-1938), who published in 1885-1888 the English language monthly anarchist periodical, The Anarchist. Later, in the 1890s, he became a member of The Legitimation League, an organisation, founded by individualist anarchists which campaigned for the legitimation of illegitimate children and free love. Seymour contributed to the journal The Adult: A Journal for the Advancement of Freedom in Sexual Relationships. Another important figure was Albert Tarn (1862-1900), a member of William Morris's Socialist League. He published between 1890-1892 The Herald of Anarchy, a monthly which propagated individualistic anarchism. Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), a brilliant writer and a poet, was also an influential individualist anarchist, who wrote the famous essay called The Soul of Man Under Socialism (1891), but he never took an active role in the movement. George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), a prominent member of Fabian Society, had a relatively brief period of toying with anarchism, which found reflection in his article "What's in a Name?" (1885) and the treatise "Anarchism Versus State Socialism" (1885), which pleaded for the abolition of all authority. Ultimately, he revoked his former views in the Fabian tract "The Impossibilities of Anarchism" (1883).

Christian anarchism

Another minor strand of late Victorian anarchism was the Christian anarchist movement, represented, among others, by Thomas Davidson's brother, John Morrison Davidson (1843-1916), a Scottish radical, journalist and barrister, and John Coleman Kenworthy (1861-1948), the author of Tolstoy: His Life and Works (1902) and a founder of the collectivist Croydon Brotherhood Church in 1894, consisting of Tolstoy's devotees, who were later known as the Croydon Anarchist Group. Christian anarchism opposed both the church and the state in favour of a literal reading of Christs teaching that saw it as preaching communal communism on earth (Ryley 120). J.M. Davidson wrote: "The true Founder of Socialism or to be accurate, Communism, was Jesus of Nazareth, and all genuine Collectivists are, consciously or unconsciously, His followers" (qtd. in Riley, 139). Tolstoy's book The Kingdom of God Is Within You, published in English translation in 1894, became the most influential contribution to radical Christian anarchism in Britain.

Literary stereotypes of anarchists

H. G. Wells with George Bernard Shaw, one of his growing number of literary friends (by E. Harries, in Hopkins, facing p. 160)

The British anarchist movement put a primary emphasis on the individuals unrestricted freedom and showed no or little inclination to violence. The only victim of anarchist terror in England was a Frenchman Marcel Bourdin, who in 1894 accidentally blew himself up in Greenwich Park due to the uncontrolled explosion of a homemade bomb intended for use abroad. The man was linked to a group of anarchists from the Autonomie Club. This incident inspired Joseph Conrad to write his only sensational novel titled The Secret Agent (1907), which portrays the image of the Jewish anarchist as an agent provocateur. The novel provides a fictionalised account of the causes of the explosion at Greenwich Park. Earlier, Henry James, inspired by the story of the German anarchist Johann Most, wrote a novel The Princess Casamassima (1886), about the planned terrorist attack in London. H. G. Wells's story "The Stolen Bacillus" (1895) presents an anarchist who steals a vial of cholera germs from a bacteriologist in order to infect the whole population of London. G. K. Chesterton's curious psychological thriller, The Man Who Was Thursday (1908), deals with a group of seven anarchists in turn-of-the-century London who call themselves by the names of the days of the week and attempt to carry out a terrorist plot. Due to its violent rhetoric anarchism gradually entered the public consciousness and had quite a noticeable effect on some late Victorian writers, artists and intellectuals. In the minds of many Victorians, the overwhelming stereotype of an anarchist was not an advocate of individual freedom, but an unscrupulous person, a criminal planning to launch revolutionary violence in the world. The threat of public peace caused by the anarchist attacks was discussed in Parliamentary debates and public speeches. Newspapers and magazines widely reported the activities of anarchist movements in Germany and Russia.

Anarcho-feminists

In late Victorian Britain, anarchist thought attracted many educated women, which contributed to the emergence of another marginal strand of anarchism known as anarcho-feminism. British anarcho-feminists called for an egalitarian society without gender inequality and womens subordinate social status. Anarchist women were inspired by the ideas of individualist anarchism and challenged the traditional notions of woman's place in family and society. They also fought against patriarchy and instances of sexism and misogyny among many male anarchists. One of the forerunners of anarcho-feminism in late Victorian Britain was Charlotte Wilson (1854-1944), the wife of a Hampstead stockbroker and an active intellectual hostess associated with the Pre-Raphaelites. Wilson was first exposed to the radical ideas as a student at Newnham College, founded at Cambridge in 1871, one of the earliest institutions of higher education for women in England. She became interested in anarchism during the trial of the Russian exiled anarchist Peter Kropotkin in Lyons, France, in 1883, and a year later she changed into a convinced and devoted anarchist. She organised the anarchist section in the Fabian Society, but did not support the Fabians political activism and therefore she co-founded in 1886 with Kropotkin an influential and long-running anarchist paper Freedom, A Journal of Anarchist Socialism, which gathered a small group of devoted collaborators, who created "the only durable anarchist organisation in Britain" (Woodcock, 195). Her essays published in the socialist newspaper Justice in 1884 were described as "the first native Victorian contribution to genuinely anarchist theory" (Oliver 30). Charlotte Wilson expressed her anarchist views in Fabian Tract No. 4:

Anarchism is not a utopia, but a faith based on the scientific observation of social phenomena. In it the individual revolt against authority, handed down to us through radicalism and the philosophy of Herbert Spencer, and the Socialist revolt against private ownership of the means of production, which is the foundation of Collectivism, find their common issue [Tract No. 2, 12].

Other prominent British women anarchists included Agnes Henry (1850-1915), the author of Anarchist Communism in Relation to State Socialism (1896), Florence (Nannie) Dryhurst (1856-1930), who taught at the International Anarchist School and contributed to the anarchist newspaper Liberty. Born in Germany, Johanna Lahr (1867-1904) was active in the anti-parliamentarian movement and in the anarchist wing of the Socialist League. Nellie Shaw (date of birth and death unknown), an anarchist feminist seamstress from Penge in Bromley, a member of the Fabian Society, was one of the founding members of the Whiteway colony, another Tolstoyan anarchist community established in 1898 in the Cotswolds, which was based on gender equality and sexual freedom. Olivia Rossetti Agresti (1875-1960), her sister, the future Helen Rossetti Angeli (1879-1969), the children of William Michael Rossetti (1829-1919), brother of the poetess Christina Rossetti and the painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, edited from 1892 to 1896 an incendiary anarchist monthly The Torch of Anarchy, which quickly gained readership and new authors. They described their teenage adventure with anarchism in a book titled A Girl Among the Anarchists, published under the pseudonym Isabel Meredith in 1903. Later both sisters changed their political views diametrically from the strand of anarchist communism to fascism under the influence of Ezra Pound.

Louise Michel, from Spirit of Revolt, frontispiece.

In the context of British anarcho-feminism mention should be made of the anarchist feminist heroine of the 1871 Paris Commune, Louise Michel (1830-1905), who established the first feminist organisation in France in 1866. In 1881, she attended the Anarchist Congress in London. In 1890, after several years of imprisonment and exile in New Caledonia, and eventually an attempt to commit her to a mental asylum, she found refuge in London, where she collaborated with Kropotkin. Michel lived semi-permanently in London for the last 15 years of her life and moved among the European anarchist exiles. Together with Agnes Henry she ran the above-mentioned anarchist free school set up at 19 Fitzroy Square in London in the early 1890s for the children of political refugees. The schools committee consisted of such prominent radicals as Peter Kropotkin, William Morris and the Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta (1853-1932). In 1892, the school was closed, when a bomb was found in the basement. It was later revealed that it had been put there by Auguste Coulon, a police agent provocateur, who worked at the school as an assistant. Michel contributed to two London-based English-language anarchist periodicals, The Torch and Freedom, and actively participated in the political debates on anarchism and women's rights. Some of her writings were translated into English by the anarcho-feminist poet and essayist Louisa Sarah Bevington (1845-1895).

Jewish anarchists

By the end of the Victorian era immigrant Jews had become a visible minority in London and other major English cities. Some 30,000 Jews settled in the East End. Although proportionally, Jews in Britain formed a small minority of the total population, increasing voices about alien menace appeared in the press and public debates. In his book The Modern Jew (1899), Arnold White linked Jewish immigrants from Russia and Poland with criminality, poverty, and anarchism (Knepper 297). Anarchist ideas began to circulate in the Jewish community of London's East End along with the influx of Jews who had left tsarist Russia after waves of violent pogroms in the 1880s. In 1888, a Jewish anarchist group, called the Knights of Freedom, was organised in the Berner Street Club. Its members were involved in the Jewish labour movement and militant atheism (Prager 69). Jewish anarchists were unjustly suspected to have been involved in ripper murders in Whitechapel (1888). The infamous Jack the Ripper was reported to be an immigrant Jew from Poland. Although some London Jews were involved in organised criminal activity, Jewish immigrants did not join anarchist groups in Britain on a significant scale. London's East End served as a one way-station for many East European Jewish immigrants on their way to America. Nevertheless, in popular image anarchism was often linked with Jewishness (Knepper 296). The hotbed of Jewish anarchist agitation in London was the Berner Street Club, which was renamed in 1885 as the International Workingmen's Educational Club. Johann Most (1846-1906), an exiled German gentile, exerted a great influence on Jewish anarchism in late 19th century London. In 1879, he founded an anarchist newspaper Die Freiheit (Freedom), which justified acts of terror and political assassination on anarchist principles. Born in present-day Lithuania, Morris Winchevsky (1856-1932), also known as Ben Netz, was a prominent Jewish socialist leader in London and a Yiddish poet. In 1885, he founded a non-partisan radical newspaper Der Arbeter Fraint (The Workers' Friend), deeply committed to Jewish workers movement. In 1892, the paper, which came under the control of Jewish anarchists, acquired the subtitle "Anarchist-Communist Organ," and was subsequently, from 1898, edited for almost two decades by Rudolf Rocker (1873-1958), another exiled gentile German anarchist, a writer and activist. Rocker taught himself Yiddish and gained recognition among Jewish anarchists, who called him jokingly an anarchist rabbi. In 1907, at the International Anarchist Congress in Amsterdam, Rocker reported about the size of British anarchism, claiming that seven provincial and four London anarchist groups were still active, and some 30,000 leaflets were distributed (Knepper 302).

Conclusion

Anarchism was never a large and well-organised movement in late Victorian Britain as in the Continent and it was ideologically much more indebted to foreign thinkers, such as Proudhon, Bakunin and Kropotkin than Godwin and Shelley. Indigenous British anarchists hardly ever supported indiscriminate violence and terror. However, in the public imagination anarchism was increasingly associated with lawlessness and violence. Anarchism in Britain, as an utopian project based on the repudiation of all constituted authority and the complete emancipation of the individual from all forms of state control, had lost much of its attractiveness by the end of the Victorian era. This was mostly due to dreadful acts of terror committed by anarchists on the Continent and widely reported by the press. The marginalisation of British anarchism was also the result of the evolution of the trade unions and the creation of the Independent Labour Party in 1893, which offered a non-violent path to social revolution.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Bantman, Constance. The French Anarchists in London, 18801914. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013.

Beer, Max, ed. A History of British Socialism. Vol. 2. London and New York: Routledge, 2002.

Bevir, Mark. "The Rise of Ethical Anarchism in Britain, 1885-1900". Historical Research, Vol. 69 (169), June 1996, 143165, 1996.

Buckley, A.M. Anarchism. Edina, Mn.: ABDO Publishing Company, 2011.

Cohen, Philip K. John Evelyn, A Critical Biography: Poetry, Anarchism, and Mental Illness in Late-Victorian Britain. Rivendale Press, 2012. [Review].

Cole, G. D. H. A History of Socialist Thought, Vol. II, Marxism and Anarchism, 18501890. London, New York: Macmillan, 1954.

Fabian Society. Tract No. 4. What Socialism Is. London: George Standring, 1886.

Hardy, Dennis. Utopian England: Community Experiments 19001945. London, New York: Routledge, 2000.

Knepper, Paul. "The Other Invisible hand: Jews and Anarchists in London before the First World War." Jewish History, 2008, Vol. 22 (3), 2008, 295315.

Kropotkin, Peter. "William Morris." Freedom, Vol. X (110), November 1896.

Marshall, Peter. William Blake: Visionary Anarchist. London: Freedom Press, 1988.

Meredith, Isabel. A Girl Among the Anarchists. Lincoln and London: Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

Nettlau, Max. A Short History of Anarchism. London: Freedom Press, 1996.

Oliver, Hermia. The International Anarchist Movement in Late Victorian London. London: Croom Helm, 1983.

Paananen, Victor N. William Blake. New York: Twayne Publishing, 1996.

Prager, Leonard. "Di Fraye Velt: London, 18913", Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies, Vol. 2 (1965) 6972.

Ryley, Peter. Making Another World Possible Anarchism, Anti-Capitalism and Ecology in Late 19th and Early 20th Century Britain. New York, London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Shpayer-Makov, Haia. "Anarchism in British Public Opinion 1880-1914", Victorian Studies, Summer, 1988, Vol. 31(4), 487516.

Spirit of Revolt. Peter Kropotkin, Louise Michel and the Paris Commune. London: Freedom Press, 1971. Internet Archive. Printed from the John Cooper Collection, held in the Spirit of Revolt Archive, Glasgow.

Sypher, Eileen. Anarchism and Gender: James's The Princess Casamassima and Conrads The Secret Agent, The Henry James Review. Johns Hopkins University Press Volume 9 (1), Winter 1988, 116.

Thomas, Matthew. "Anarcho-Feminism in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain, 1880-1914." International Review of Social History, 47 (1), 2002, 131.

Wilson, Charlotte. Anarchist Essays, ed. by Nicolas Walter. London: Freedom Press, 2000.

Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1983.

Created 10 May 2023