Except for the scan of the book cover, the illustrations here all come from our own website. Please click on them to enlarge them, and for more information about them. — JB.

In the autumn of 1888 the East End of London was possessed with fear as the serial killer known as ‘Jack the Ripper’ exercised his bloody project, murdering at least five women, and possibly more. Of course, the Whitechapel murderer’s tale is well-known. Often regarded as the world's first mass killer, and never caught, the person responsible for the crimes has stimulated an industry of speculation. Some of the suspects are reasonably plausible: Aaron Kosminski, a Polish barber, is high on the list, and so is Michael Maybrick, a singer and composer whose involvement has recently been examined in a febrile study by Bruce Robinson; others, such as the painter Walter Sickert (favoured by crime writer Patricia Cornwall), are unlikely candidates. At the same time, many commentators have placed the blame on a wider, institutional guilt. Within the domains of the pseudo-history known as ‘Ripperology’ conspiracy theories abound, with each more convoluted and absurd than the last. The Ripper’s brief career is full of missing gaps and it is unlikely we will ever know his identity.

Surprising, too, is how little is known of his victims. Dismissed as prostitutes from the bottom of Victorian society and implicitly of no value, these poor souls have been entirely eclipsed by their terrifying killer, erased from the record except as the passive objects of a grotesque blood-lust. It is only now, more than a century after the event, that they have been reinstated. Hallie Rubenhold takes up their case in her fascinating study, The Five: the Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper. Presented as a feminist history, and deploying many of its familiar tropes, Rubenhold traces the biographies of the so-called ‘canonical five’ – Mary Ann Nicols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly. Avoiding the oft-chronicled and salacious circumstances of their deaths, Rubenhold concentrates instead on the incredible difficulties each faced. Broken relationships, alcohol, illness, petty crime, and above all else the grinding conditions of late Victorian poverty are shown to be the defining features of their miserable careers.

Three of the many Victorian paintings dealing with ‘fallen women’. Left to right: (a) Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Found, in which a countryman finds his former sweetheart has become a denizen of the streets. (b) The fate that often awaited such women: Richard Redgrave’s The Outcast. (c) The ultimate fate of the outcast: G. F. Watts’s Found Drowned.

Rubenhold is especially effective in demonstrating how misogynistic prejudice has contributed to the victims’ lowly status. Though traditionally described as prostitutes, this was not entirely the case. Rather, the author demonstrates how each was a ‘fallen woman’, with most of them starting off as wives and mothers. Particularly telling is the account of Annie Chapman, who was a coachman’s wife and enjoyed for a while a reasonably comfortable life-style; a photograph of 1869 shows her as a member of the respectable servant-classes, wearing a lustrous dress and accompanied by her husband. There is no evidence, Rubenhold insists, that Chapman was ever a prostitute but, like the others, was reduced to destitution by a deadly combination of economic misfortune and the unforgiving social policies of the time. In an age when only the very wealthy were protected from privation, it was all too easy to fall into poverty and these women were undervalued, Rubenhold shows, because they were poor. In an age of vast inequality, their fate is emblematic of late Victorian attitudes as the road to ruin, so often lamented in art of the time, threatened to claim fragile lives.

Left: The women’s yard at Southwell Workhouse (with a re-enactor). Right: Rough sleepers in Gustave Doré’s ‘The Bull’s-Eye’, an illustration for Douglas Jerrold’s London, p. 38.

Theirs was an existence of squalor, and Rubenhold vividly conveys the unsteady movement between living in a work-house or coping with the stench of overcrowded rooms, violence, the descent into crime, the filth of the doss-houses and the sheer physical suffering of sleeping under the stars, on the pavement or slouched in shop doors. Drawing on the reports of Henry Mayhew, Charles Booth and others writing of the ‘people of the abyss’, she describes the visceral facts of life on the bottom rung, noting for example how the Victorian masses were indecently crowded together:

One bed may have sufficed for an entire household.... Parents, children, siblings and extended family dressed, washed, engaged in sex and [if there were no lavatory close by], defecated in front of each other. As one family prepared a meal, a sick child with a raging fever might be vomiting into a chamber pot beside them, while a parent or sibling stood by half-naked changing their clothes. Husbands and wives made future children while lying beside present ones. Little about the human condition in its most basic form could be concealed. [23]

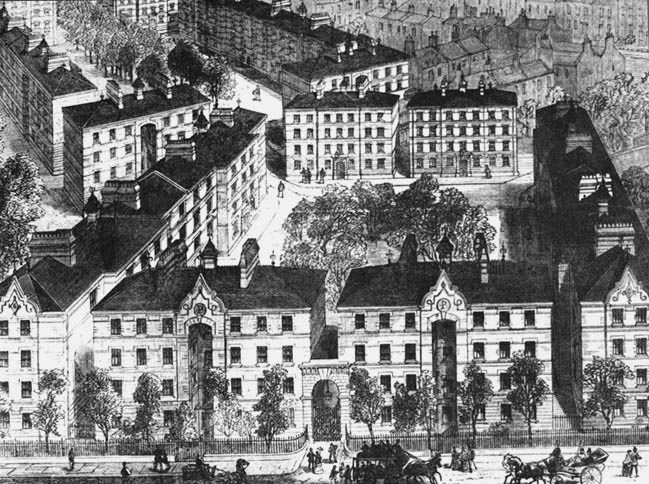

The Peabody estate for the ‘respectable poor’, on Blackfriars Road, London, in 1871.

It is in this social milieu that the Ripper’s victims scratched a bare living, and the author spares us none of the gross details. Her research into their individual circumstances, likewise, is remarkably complete. Based on newspaper reports, coroners’ reports, old photographs and other ephemera, she recovers a great deal of information which on the face of it seems inaccessible and lost to time. In her sections on Elizabeth Stride, for example, she uncovers details of her early life in Sweden along with extracts from her medical record, including a photograph of the house where she grew up; Annie Nicols is recounted as a Peabody tenant, struggling to maintain respectability; while Catherine Eddowes, from Wolverhampton, is glimpsed making money on the streets not as a prostitute but as a proclaimer and possibly a writer of ballads.

Rubenhold’s writing is vivid, drawing us into a sordid world. But there are some weaknesses. Though astute, the author is sometimes too dependent on speculation. There are many conditionals – and in search of nuance she makes some assumptions which, in the absence of a firm historical record, are impossible to check and have to be left to the domain of the likely and the possible.

With these reservations, The Five is an important book. Sympathetically written, full of telling information, wide-ranging in its reconstruction of the social setting and cleverly argued, it adds another dimension to our understanding of the crimes. Above all else, Rubenhold dignifies the women who were so brutally taken away by exploring their stories in the greatest possible detail. No longer names, they emerge from their hellish urban setting as poor forked creatures whose lives were blighted by disadvantage.

Few will be able to read this account without being moved, and our view of the terrible events in late Victorian Whitechapel will never be the same again. It engaged and shocked me. It also made be angry, prompting a single question: would the Ripper have been caught if his victims had been virtuous middle-class women living in Kensington? I suspect he would.Related Material

- Clare Collet and Jack the Ripper

- Prostitution in Victorian England

- Jack London’s Autobiographical Account of the East End Slums: The People of the Abyss

- How Safe was Victorian London?

Works Cited

Cornwall, Patricia. Portrait of a Killer. New York: Putnams, 2002.

Robinson, Bruce. They All Love Jack. London: Fourth Estate, 2015.

[Book under Review] Rubenhold, Hallie. The Five: The Untold Stories of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper. London: Doubleday, 2019. Hardback. 432 pp. ISBN 978-0857524485. £16.99.

Created 18 May 2019